In the S-1 form that NerdWallet filed with the SEC, prior to going public, the company stated that “NerdWallet exists for one reason: to empower consumers and SMBs with financial guidance they can trust.”

NerdWallet attempts to do this by providing, among other things, reviews of financial products and lists of the best financial products in different categories. If, for example, a consumer is thinking about opening up a new checking account and searches for “best checking account” in Google, the first organic result they would see right now is a list from NerdWallet — 10 Best Checking Accounts of July 2022. Each product on the list has a rating (0-5) and a set of characteristics (fees, interest rates, etc.) as well as, in most cases, a review from an expert on the NerdWallet editorial team.

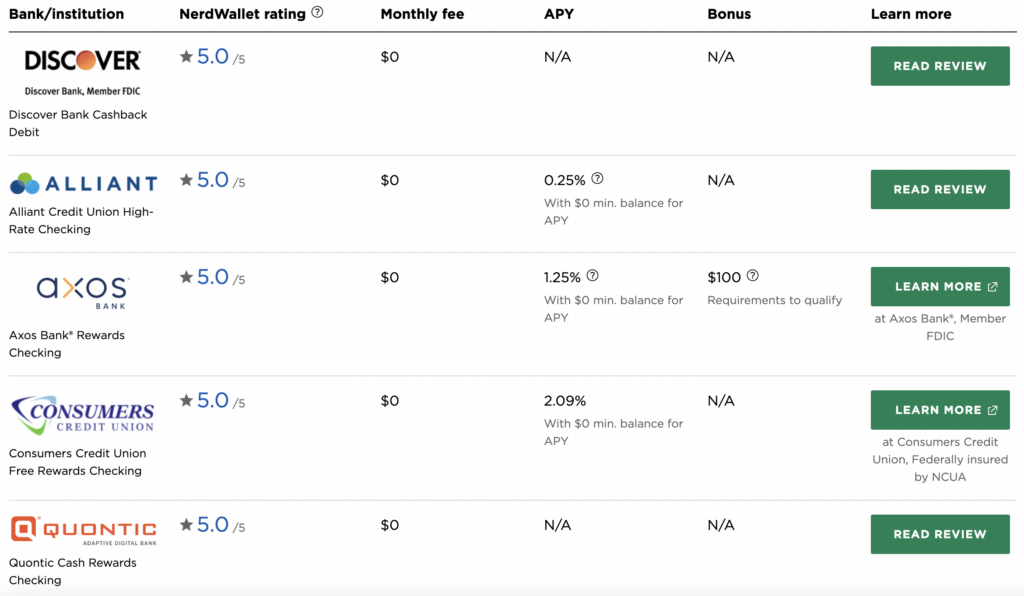

Here’s what the top of the list looks like:

There are a few things about this list that strike me as odd:

- None of the top four banks in the U.S. — JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and Citi — are on this list, which is strange given that a significant portion of banked consumers in the U.S. have a checking account with one of those four banks. Does this mean that those consumers chose badly when selecting their checking accounts? Seems unlikely, but I guess it’s possible.

- By contrast, three of the top five banks listed here are ones that I have never heard of. Now, I’m not the end-all-be-all expert on checking accounts in the United States, but I like to think I’m a fairly knowledgable observer of the market and I’d further like to think that if these are indeed the best five checking accounts being offered right now, I would have heard of at least a majority of the banks offering them.

- I’m also a bit confused as to how all five checking accounts received full five-star ratings. I mean, the products are pretty different. Some pay interest (all the way up to 2.09%!). One of them pays out a $100 sign-up bonus. Some are offered by bigger financial institutions that, I’m guessing, provide significantly better digital banking capabilities. Yet NerdWallet considers them all equally the best. Huh.

- And on that note, three of the products have reviews that I can read; two (Axos and Consumers Credit Union) don’t. Why is that? Did NerdWallet’s editorial team not review those two products? If not, how did they make this list in the first place? And why did they receive 5-star ratings?

Obviously, I’m being a bit facetious here.

I know perfectly well, and so do you, why this list was constructed the way that it was. All the companies featured on it are paying fees to NerdWallet for the new checking account applications that NerdWallet generates for them.

There is some strong editorial content and reviews buried in places within this list, but the list itself — the first thing that a consumer sees when they ask NerdWallet for help — is entirely defined by the commercial relationships NerdWallet has with its financial partners.

To put it bluntly, this is not the “trustworthy financial guidance from deeply knowledgable experts”, that NerdWallet promised in its S-1. And this isn’t just me saying this. NerdWallet has an average review of 1.6 out of 5 on TrustPilot and 1.67 out of 5 with the Better Business Bureau.

For a business that’s entirely built on trust, that’s bad.

And here’s the most important part — NerdWallet knows that this is bad. They understand that these types of lists are bad for their users and that they degrade the long-term value of the company and its brand. In fact, they go out of their way to talk about the importance of not prioritizing short-term revenue over the long-term value of customer trust in their S-1!

One of our fundamental values is to build our business by making decisions based upon the best interests of our users, which we believe has been essential to our success in building user trust in our platform and increasing our user growth rate and engagement. We believe this best serves the long-term interests of our company and our stockholders. In the past, we have forgone, and we may in the future continue to forgo, certain expansion or short-term revenue opportunities that we do not believe are in the best interests of our platform and our users, even if such decisions adversely affect our results of operations in the short term.

And yet, it’s impossible to look at these ‘best product’ lists on NerdWallet and feel like the company is fully upholding its own values.

And they’re not an outlier! Every company in this business — Credit Karma, Mint, The Points Guy — understands the strategic danger of falling into this exact trap and has fallen headfirst into it anyway.

So, you have to ask yourself — why is it that smart, disciplined people who seem genuinely committed to a customer-centric mission make product decisions that they know are going to be bad for the long-term health of their business and counterproductive to their mission?

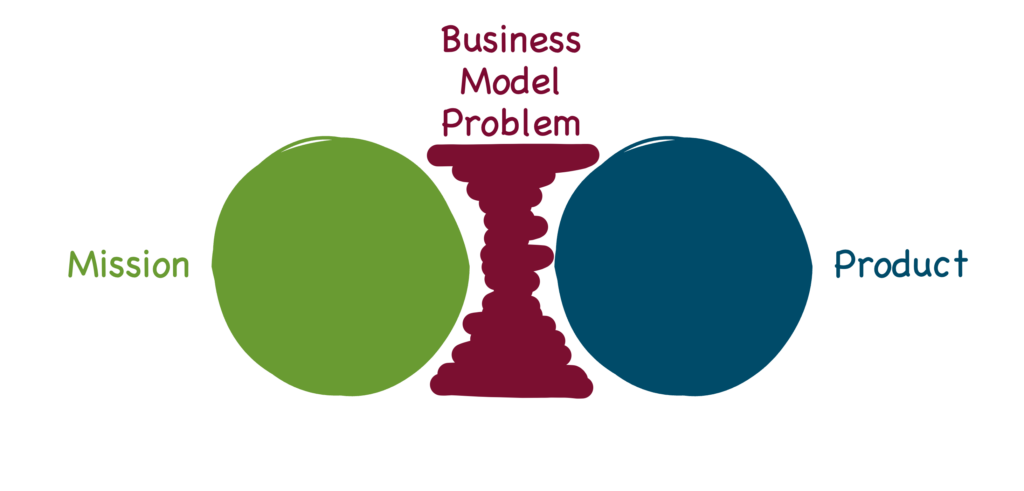

The answer is simple — it’s a business model problem.

Identifying Problematic Business Models

The easiest way to spot a problematic business model is to look for a divergence between a company’s mission statement — its explanation for why it exists and what its overall goal is — and its core product(s).

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

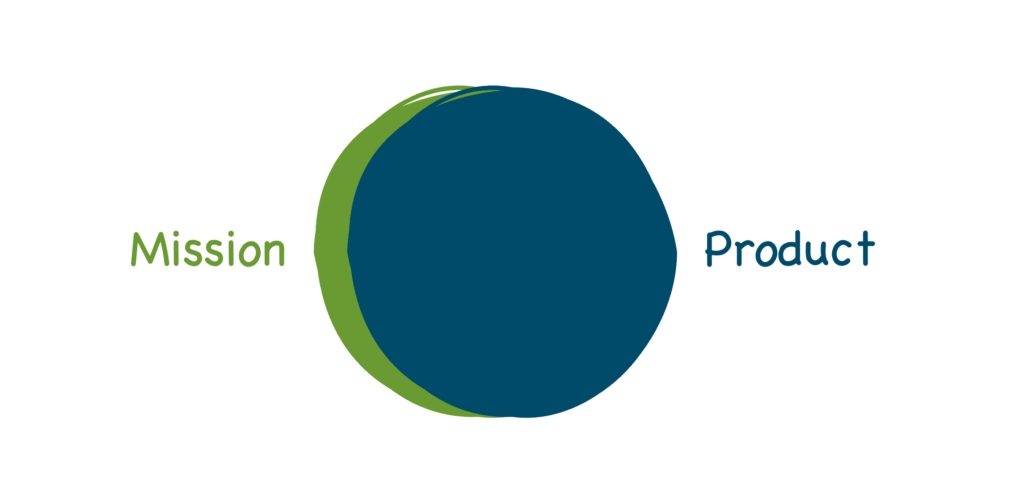

When companies start out, there’s usually a near-perfect overlap between their mission and their product, even if the product itself is still in its early MVP form.

This is because the underlying motivation that drove the creation of the product is usually reflected in the founding story and mission of the company.

NerdWallet is a good example, as its CEO and co-founder Tim Chen relates (emphasis mine):

In 2009, my sister asked me which credit card was best for an expat living in Australia. I said, “Let me Google that for you,” expecting to have an answer in a few minutes. Instead, I found a lot of marketing materials, but nothing resembling a clear, well-researched answer. So I built her a spreadsheet to help and got a little carried away, as nerds are wont to do. Before I knew it, that spreadsheet was forwarded again and again to others who were all looking for an answer to one, simple question: “What’s the best credit card for me?” From there, NerdWallet’s first credit cards tool was built and our mission was born.

However, over time, the utility and experience of some companies’ products will diverge from their mission statement. Put simply, the products get worse.

Logically, this doesn’t make sense. As companies grow and get access to more resources, their product(s) should get better and become an even stronger testament to their level of commitment to their founding mission.

When this doesn’t happen; when you start to see a divergence between a company’s product(s) and its mission, that’s when you know you have a business model problem.

NerdWallet is one example.

For another example, let’s look at the company that NerdWallet (and all other lead aggregators) depend on.

Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.

And if you remember what it felt like to use Google Search, back when it was first introduced more than 20 years ago (if your memories go back that far), you’ll likely agree that it felt a lot like the world’s information was, for the first time ever, truly at your fingertips, as Charlie Warzel at The Atlantic recounts:

One can’t really overstate the way that Google Search, when it rolled out in 1997, changed how people used the internet. Before Google came out with its goal to crawl the entire web and organize the world’s information, search engines were moderately useful at best. And yet, in the early days, there was much more search competition than there is now; Yahoo, Altavista, and Lycos were popular online destinations. But Google’s “PageRank” ranking algorithm helped crack the problem. The algorithm counted and indexed the number and quality of links that pointed to a given website. Rather than use a simple keyword match, PageRank figured that the best results would be websites that were linked to by many other high-quality websites. The algorithm worked, and the Google of the late 1990s seemed almost magical: You typed in what you were looking for, and what you got back felt not just relevant but intuitive. The machine understood.

And yet, as that same Atlantic article goes on to argue, it feels today as if Google Search has somehow managed to go backward:

Most people don’t need a history lesson to know that Google has changed; they feel it. Try searching for a product on your smartphone and you’ll see that what was once a small teal bar featuring one “sponsored link” is now a hard-to-decipher, multi-scroll slog, filled with paid-product carousels; multiple paid-link ads; the dreaded, algorithmically generated “People also ask” box; another paid carousel; a sponsored “buying guide”; and a Maps widget showing stores selling products near your location. Once you’ve scrolled through that, multiple screen lengths below, you’ll find the unpaid search results. Like much of the internet in 2022, it feels monetized to death, soulless, and exhausting.

The root cause that Warzel identifies for the decline in the quality of Google’s search experience isn’t surprising or unexpected; it’s the business model (emphasis mine):

Google has built wildly successful mobile operating systems, mapped the world, changed how we email and store photos, and tried, with varying success, to build cars that drive themselves. This story, for example, was researched, in part, through countless Google Search queries and some Google Chrome browsing, written in a Google Doc, and filed to my editor via Gmail. Along the way, the company has collected an unfathomable amount of data on billions of people (frequently unbeknownst to them)—but Google’s parent company, Alphabet, is still primarily an advertising business. In 2020, the company made $147 billion in revenue off ads alone, which is roughly 80 percent of its total revenue. Most of the tech company’s products—Maps, Gmail—are Trojan horses for a gargantuan personalized-advertising business, and Search is the one that started it all.

Again, it’s important to emphasize that a.) Google understands better than anyone how important its search product is, strategically, to its business, and b.) Google employs a massive number of brilliant, dedicated, customer-obsessed employees that are focused on upholding and improving the quality of its search engine.

And yet, again, it’s difficult to argue that the experience of using Google Search today is significantly better (or better at all) than it was 10 years ago.

So, what’s the takeaway?

No matter how smart, disciplined, and customer-centric you are, at the end of the day, you are your business model.

We Have a Business Model Problem in Financial Services

Why does this matter?

It matters because, when I look around the financial services industry, I see problematic business models wrecking financial products and dragging financial services companies away from their laudable missions.

Most of these problematic business models have something in common — they are designed to give customers the illusion that they are getting a valuable financial product for free while shifting the true costs of providing that product into less obvious, more pernicious places.

I’ll give you three examples.

1.) Checking

Most checking accounts are, ostensibly, free. They come with certain constraints, like minimum balance requirements or the need to make a specific number of debit card transactions per month, but within those constraints, they are usually presented as being free or very low cost.

The trouble is that safely storing a customer’s deposits, giving them constant access to their funds anytime and anywhere, and covering the occasional cashflow shortfall isn’t free for banks. It costs money. The need to recoup that expense and generate a positive return on top of it has, historically, incentivized banks to create devious and punitive fees, like overdraft and NSF fees, which can have a devastating impact on the financial health of their customers, particularly low-to-moderate income customers.

Wells Fargo, whose mission statement is helping customers succeed financially, generated more than $1 billion in overdraft fee revenue in the first three quarters of 2021. It’s difficult to see how the current design of its deposit products is serving that mission.

2.) Stock Trading

Thanks to Robinhood and the pressure that it put on all of its competitors, stock trading is now, for the most part, free. That certainly seems to be well aligned with Robinhood’s mission to democratize finance for all, but if we look at the full mission statement on Robinhood’s website, we notice something else (emphasis mine):

Robinhood’s mission is to democratize finance for all. We believe that everyone should have access to the financial markets, so we’ve built Robinhood from the ground up to make investing friendly, approachable, and understandable for newcomers and experts alike.

Does Robinhood make investing understandable for newcomers? More precisely, is Robinhood incentivized to make investing understandable for newcomers?

To answer that question, we need to understand how Robinhood makes money.

Instead of charging commissions on individual trades, Robinhood relies on Payment for Order Flow (PFOF):

PFOF is a practice in which brokers receive money for sending orders to a third-party, usually a market-maker.

When you buy $100 of Apple, for example, Robinhood (the broker) has the choice of directing your trade somewhere. While it could send your order straight to a stock exchange, market makers are usually able to offer a better price.

Instead of costing $150 per share, for example, Citadel Securities (the market maker) might be able to get it for you for $149. (The difference is usually fractions of a penny, but this is easier to keep track of.)

The result is a $1 savings. Robinhood keeps some of that, while passing on a portion to you, the user, in the form of “price improvement.” Robinhood has effectively earned money from sending your trade to Citadel Securities.

PFOF generally leads to better outcomes for retail traders (price improvement), retail brokers (fee revenue), and wholesalers (a better spread on internal trades). However, it also creates some not-so-great incentives:

The value of the PFOF inventory Robinhood offers is a function of two things: the number of active users and the average “noise” of their trades.

Noise is a function of both volume (number of trades) and style of trading. In general, Robinhood wants as many aggressive, high volume traders who are trading in basically random patterns as it can get.

Which helps explain Robinhood’s fondness for helping its customers not just buy stocks, but buy options on stocks.

Options — high-leverage bets on the future value of specific stocks — are profitable for Robinhood because:

(1) people may not own a ton of options, but they trade them a lot; you get more volume from options traders than you do from boring stock investors, and (2) spreads are high and it is lucrative to trade against retail options traders, so market makers are delighted to pay Robinhood large amounts of money for the privilege.

And options trading, in particular, can be very difficult for newcomers to understand and can lead to tragic consequences when they don’t.

3.) BNPL

According to a forecast by Worldpay, BNPL will account for about $438 billion, or 5.3%, of the global e-commerce transaction value by 2025, up from 2.9%, or $157 billion, in 2021. If true, that would (according to Worldpay) make BNPL the fastest-growing e-commerce payment method through 2025 in some of the largest economies in the world, including the U.S., UK, Canada, India, and Brazil.

BNPL providers would argue that this projected growth is due to the win-win arrangement that BNPL fosters between consumers and merchants — the consumer gets access to free, frictionless financing and the merchant gets the sale. Indeed, Afterpay’s stated mission is to power an economy in which everyone wins.

Sounds great, but the trouble is that we are seeing increasing evidence of consumers misusing BNPL, as this new payment option proliferates across retailers’ checkout pages:

nearly 70% of buy now, pay later users admit to spending more than they would if they had to pay for everything upfront, according to a survey from LendingTree.

In fact, 42% of consumers who’ve taken out a buy now, pay later loan have made a late payment on one of those loans, LendingTree found.

Gen Zers are more likely to miss a payment and tap BNPL for everyday purchases rather than big-ticket items, according to a separate survey by polling site Piplsay.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone. The reason that most pay-in-4 BNPL products are free for consumers is that merchants are offsetting the risk of those 0% loans through the fees they pay to the BNPL providers. And the reason that merchants are willing to pay those fees (which are often quite a bit higher than credit card fees) is because BNPL is very effective at tempting consumers into buying more than they otherwise would.

That’s obviously great for merchants, but I’d hardly describe that as an economy in which everyone wins.

Time to Ask Tough Questions

Under normal conditions, I would have expected many of these problematic business models to start burning themselves out. After all, if your business model is contributing to a degradation in the quality of your product, eventually you’d expect customers to revolt or even for regulators to start objecting.

And in the case of banks’ checking account products and overdraft fees, that’s exactly what happened. It took a while, but eventually consumers voted with their feet, regulators like the CFPB piled on, and overdraft fees started getting reduced or eliminated. The system worked.

Unfortunately, within the fintech ecosystem, conditions have not been anywhere close to normal for the last 5 years. Fintech, like the tech industry more broadly, was awash in excess capital and whatever scrutiny that might have normally been applied to problematic business models was drowned out by chants of ‘grow, grow, grow!’, as Derek Thompson at The Atlantic recently noted:

It was as if Silicon Valley had made a secret pact to subsidize the lifestyles of urban Millennials. As I pointed out three years ago, if you woke up on a Casper mattress, worked out with a Peloton, Ubered to a WeWork, ordered on DoorDash for lunch, took a Lyft home, and ordered dinner through Postmates only to realize your partner had already started on a Blue Apron meal, your household had, in one day, interacted with eight unprofitable companies that collectively lost about $15 billion in one year.

These start-ups weren’t nonprofits, charities, or state-run socialist enterprises. Eventually, they had to do a capitalism and turn a profit. But for years, it made a strange kind of sense for them to not be profitable. With interest rates near zero, many investors were eager to put their money into long-shot bets. If they could get in on the ground floor of the next Amazon, it would be the one-in-a-million bet that covered every other loss. So they encouraged start-up founders to expand aggressively, even if that meant losing a ton of money on new consumers to grow their total user base.

As long as money was cheap and Silicon Valley told itself the next world-conquering consumer-tech firm was one funding round away, the best way for a start-up to make money from venture capitalists was to lose money acquiring a gazillion customers.

This ‘millennial lifestyle subsidy’ period, as Thompson calls it, gave fintech companies an extended grace period, in which they wouldn’t be forced to ask themselves tough questions about their business model. Shit, over the last couple of years in fintech, you barely needed a business model at all; just a pitch deck explaining how you would convert investors’ cash into new users.

Fortunately, at least from my perspective, those days are over. Public and private fintech company valuations are coming back down to Earth, interest rates are rising, and VCs are suddenly caring a lot less about growth and a lot more about profitability.

We are now, finally, being forced to ask tough questions about some of the dominant business models in fintech.

Here are a few such questions that I am particularly keen on:

- Will consumers pay for truly unbiased financial advice? New-school PFM apps like Monarch Money ($7.50/month for the premium product) and Copilot ($8.99/month) certainly seem to think so. I love their optimism, although I think a sustainable value exchange in the PFM world will require going way beyond simple budgeting and credit score monitoring.

- Can subscription fees work in deposits and short-term lending? Short-term lending, which is what overdraft protection functionally is, is expensive to offer. However, it’s also extremely valuable for certain customer segments that use it strategically to manage recurring cashflow imbalances. I’ll be curious to see if fintech companies like Brigit can succeed at crafting a specific product for this customer segment using a transparent subscription pricing model.

- Will neobanks be able to successfully jump into longer-term lending? If we can’t retrain consumers to pay subscription fees for deposits and short-term lending (entirely possible), then we will need neobanks that are currently offering these services for free (Chime, Current, etc.) to successfully cross the chasm into longer-term lending (unsecured installment, auto, credit card, etc.) in order to cross-subsidize their existing accounts. Alternatively, we may see fintech lenders get there first by working backward from lending into deposits (LendingClub and SoFi are the furthest along here).

- Will we see other types of embedded payment solutions get traction? The appeal of BNPL is the combination of flexibility (pay with something other than the money in your checking account) and convenience (it’s offered as an option directly within the checkout process). Merchants are particularly fond of credit-based solutions because they enable consumers to spend money they don’t have, but I wonder if merchants would consider offering alternative BNPL-like embedded payment products that don’t lead consumers to overspend? Accrue Savings (Save Now, Buy Later) and Kasheesh (splitting payments across debit, credit, and gift cards) are two to watch on this front.

- Will PFOF die? It seems very possible, for two reasons. First, the SEC doesn’t like it and may rulemake it out of existence. Second, Robinhood, the standard-bearer for PFOF, has had a rough go of it lately. As stock prices have dropped, the rampant speculation that Robinhood so effectively courted and monetized during the pandemic has dissipated and Robinhood’s monthly active users have plummeted (down 5.5 million since Q2 of 2021). This has made Robinhood competitor Public look really good by comparison. In contrast to Robinhood, Public positions itself as a platform for long-term investing. The company very loudly moved off of PFOF and now makes money through a combination of securities lending, interest on cash balances, and optional tips from customers.

- Will tipping become the next overdraft? Today, many fintech companies offer customers the option to leave a tip. These requests for tips have mostly, so far, been implemented with a fairly light touch. I wonder if we will see a fintech company, under pressure from investors to pivot to profitability, succumb to the temptation to change their tipping strategy to more strongly encourage, cajole, or even trick customers into giving bigger or more frequent tips? And if you think there’s no way that would ever happen, I’ll just remind you that overdraft protection started as a very light-touch courtesy service offered by banks.

Trust That Profits Will Follow

Embracing a business model that prioritizes long-term customer value over short-term revenue is not easy.

When the automated savings app Digit switched from being free to charging a $2.99 per month fee five years ago, its customers absolutely flipped out (Digit was eventually acquired by Oportun for $211 million).

But I think the time to make this leap is now. Investors expect profitability and consumers (and regulators) are increasingly frustrated with business models that impose hidden and unequal costs on customers.

They would rather just pay a fair price for an insanely great product.

And that’s a model that can work, as Steve Jobs once explained:

If you keep your eye on the profit, you’re going to skimp on the product. But if you focus on making really great products, then the profits will follow.