September has been a busy month.

It was my first foray back onto the fintech conference circuit since returning from paternity leave.

(Note – my wife will surely be canonized as a Saint one day for her tireless work caring for our kids while I’m traveling. She’s incredible.)

In sequential weeks, I attended Finovate Fall (check out my recap) and the TruStage Ventures Fintech Summit. At both events, I was asked to give a talk on the trends that are shaping the future of fintech.

I love being asked to do this because it’s a very useful forcing function – which of the 1,000 trends that I’ve been researching and writing about should I surface for a 15-30 minute presentation? Which trends are most worthy? Which are most relevant to my audience (bank and credit union executives, in these cases)?

Between the two presentations, I covered 9 different trends. And I thought it would be useful to share them with you.

So, without further ado, 9 trends shaping the future of fintech:

#1: Legacy Bank Technology Gets an Upgrade

It has taken us a while to get here, but I think we’re now finally at a place where we will start to see the fusion of bank-quality business models and Silicon Valley-quality technology.

Why do I think this?

Because there are now mechanisms in place across the industry to help make this fusion happen, regardless of the sophistication and intent of the companies involved.

For banks and credit unions that want to partner with or procure technology from fintech companies but don’t know where to start, we now have a plethora of funds and accelerators (hi TruStage Ventures!) specifically designed to bring banks and credit unions together with fintech companies. These funds and accelerators also help fintech companies that want to work with banks and credit unions but don’t have a lot of experience navigating those companies’ org charts, procurement processes, and technology stacks.

For banks that are a bit more sophisticated on fintech, we are in an environment in which acquisitions are a strong possibility. These banks have conditioned their boards and shareholders to understand that you have to pay a premium for technology (relative to the way that they value other banks for M&A), and many fintech companies (particularly the more niche ones that never had expectations of a massive exit) are now much more excited about the possibility of an exit via a bank acquisition than they might have been a few years ago.

And, perhaps most importantly, for banks and credit unions that still somehow think that fintech isn’t important or worth worrying about, there is still a strong likelihood that they will indirectly benefit from fintech technology thanks to the slow hoovering up of fintech companies that the core banking vendors and other legacy tech providers for banks and credit unions have started (and will continue) to do.

Fintech is finally a rising tide that is lifting all good business models.

#2: There’s No Problem Too Boring for Fintech

An observation that I’ve had over the last couple of years – there is an inverse correlation between the amount of money being invested in fintech and how boring the fintech products are that get built with that money.

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Between 2019 and 2021, there was a TON of money invested in fintech. The resulting fintech products that were built were ones that were obvious, easy, quick to build, glamorous, and often personally important to the founders. This is why we ended up with more neobanks than I could keep track of, BNPL for everything, fractional stock and alt investing, so many more PFMs (everyone likes to build the PFM they personally want), and ‘DeFi mullet’ bank accounts that literally no one was asking for.

It was like fintech art camp. Everyone got to show up and build whatever they wanted, and no one was willing to say, “So, that tie rack that you made out of two-by-fours? Yeah, your dad isn’t going to want that.”

Starting in 2022 and especially in 2023, the vibe has been very different. Money has become harder to find, and the tourists (founders and investors) have moved on to AI. The folks who are left in fintech are my favorite people. They have a high tolerance for hard work. They like solving complex challenges and learning non-obvious things. And, most importantly, they are drawn to boring stuff because they know that’s often where value hides.

Just look at the stuff that I’ve been covering in the newsletter recently:

- Corporate cards and spend management (it’s still wild to me how much interest and activity there is in this, let’s be honest, boring-as-hell corner of financial services).

- Treasury and balance sheet management (suddenly everyone’s favorite area, post-SVB).

- Loan servicing, collections, and insurance (I’ve been banging the drum for more fintech innovation in these areas forever … nice to see it finally ramp up a bit).

- Fraud data consortiums (I have an irrational love for this particular trend).

- Escheatment management (I literally didn’t know what escheatment was a month ago!)

I’m a nerd. I don’t love it when the things I like become too popular.

It’s not like I was going to walk away from fintech for becoming too popular … I’m not a hipster.

Still, it’s been nice to see fintech become a bit more boring.

#3: The Future is Niche

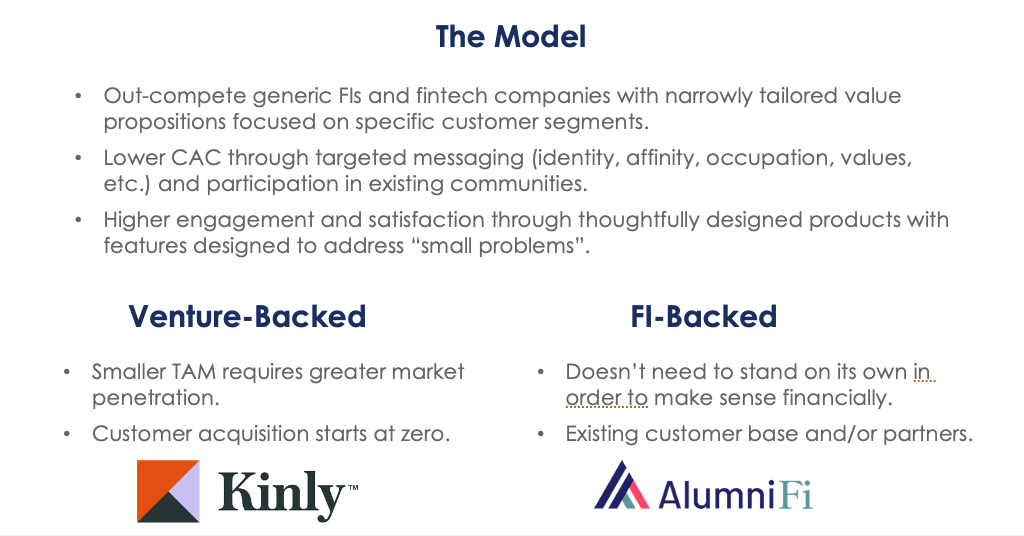

The last few years of fintech have demonstrated that there is a big appetite for niche digital products in financial services … and a very narrow path forward for niche neobank business models.

We’ve talked about niche neobanks in this newsletter a lot over the last few years.

The idea is compelling.

You build a more tailored version of standard bank products that are focused on serving a specific customer segment. These products aren’t necessarily 10x better than standard products in any one area, but they don’t have to be because they are 1.5x or 2x or 3x better in a whole bunch of different areas. They solve “small problems”, which aren’t actually so small for the consumers that are constantly dealing with them.

And on the customer acquisition side, you can be more targeted in your marketing because of your focus on a specific segment, and you can tap into existing digital communities that are already serving that segment.

The problem, as I wrote about a while back, is the business model. We’ve now seen numerous niche neobanks struggle or go out of business because they haven’t been able to grow enough to hit their investors’ goals. It’s really hard for these to be “return-the-fund” winners.

I personally think this is more of a condemnation of the game that most VC firms are playing than the viability of niche neobanking as a category, but still — it is what it is.

That said, we deserve a financial services ecosystem that is populated by these niche financial services products.

And I think we may end up getting what we deserve, thanks to community banks and credit unions. We’re starting to see these financial institutions launch niche digital brands (AlumniFi from MSUFCU and Roger from Citizens Bank of Edmond).

This makes sense. Community banks and credit unions can benefit from the things that niche neobanks are good at (customer/member acquisition, engagement, deposit gathering, etc.), but these spin-off digital brands don’t need to stand entirely on their own. As long as they are positively contributing to the financial institution’s mission and already-profitable business model, then it’s worth doing.

Obviously, community banks and credit unions will need some help to build and launch new digital products (Nymbus is the partner behind both Roger and Alumnifi), but I see a big future for the niche neobank value prop, which makes me happy.

#4: Emotion Comes to PFM

In a survey that I conducted a while back, I asked consumers, “What’s crucial to the future of your financial success?” Only 1% mentioned banks. The other 99% talked about a range of needs that are, for the most part, totally unaddressed by traditional financial products.

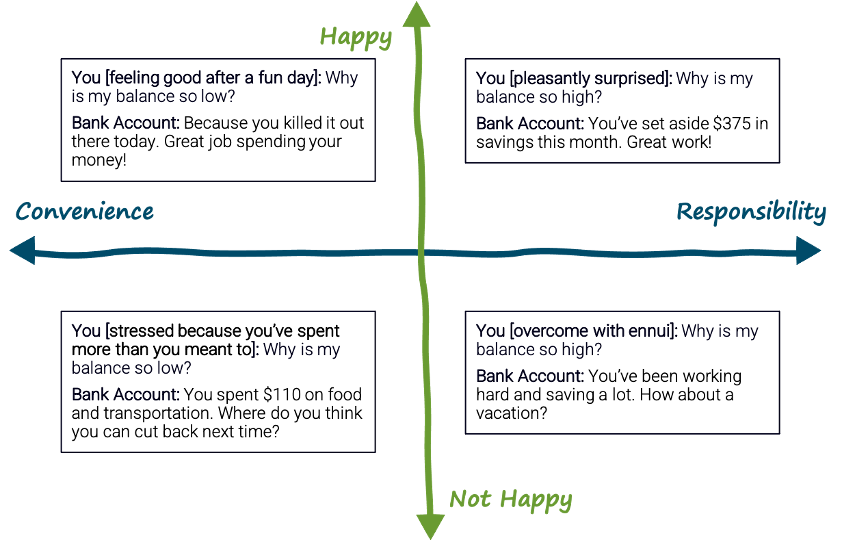

One of the biggest unmet needs was this – developing a better relationship between money and happiness.

So much of what we help consumers with in financial services is compressed onto a simple continuum, with convenience on one end and responsibility on the other end. You’re either living your life as seamlessly and conveniently as possible, or you’re miserly counting every penny and tracking every transaction.

What we’re not measuring is happiness. Which purchases are making customers happy? Which ones are making them miserable?

We need to establish this baseline before we can give advice.

Fortunately, new PFM apps are starting to do this. Allo, which I wrote about here, is a good example. It’s a PFM app, but it’s specifically designed to be used sparingly and to help users reflect on their recent purchases (did this bring you joy or not?) before offering you any insights or advice.

More of this, please!

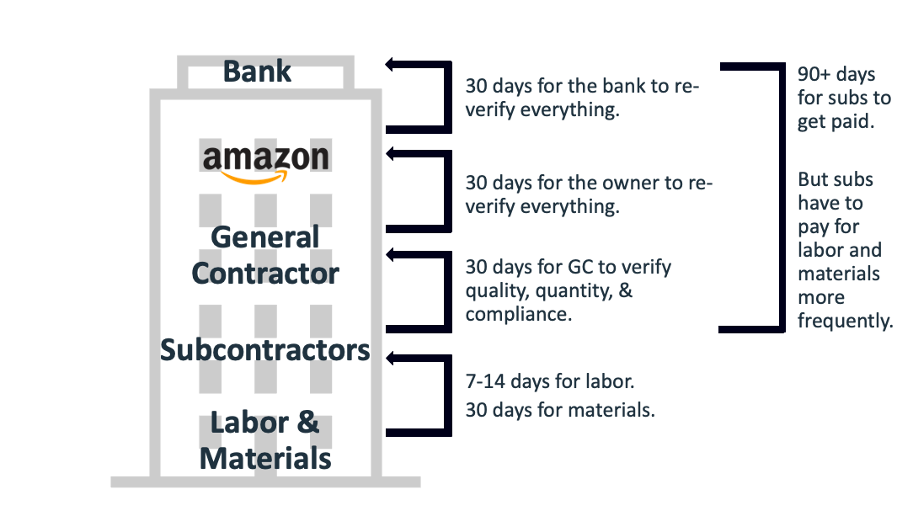

#5: Embedded Finance Uncovers New Problems

This was the subject of an entire essay last month, so I won’t belabor the point here.

All I’ll say is that the most exciting thing about embedded finance (which, I know, has been subjected to far too much hype) is its ability to help uncover and solve problems in financial services that are being completely ignored today.

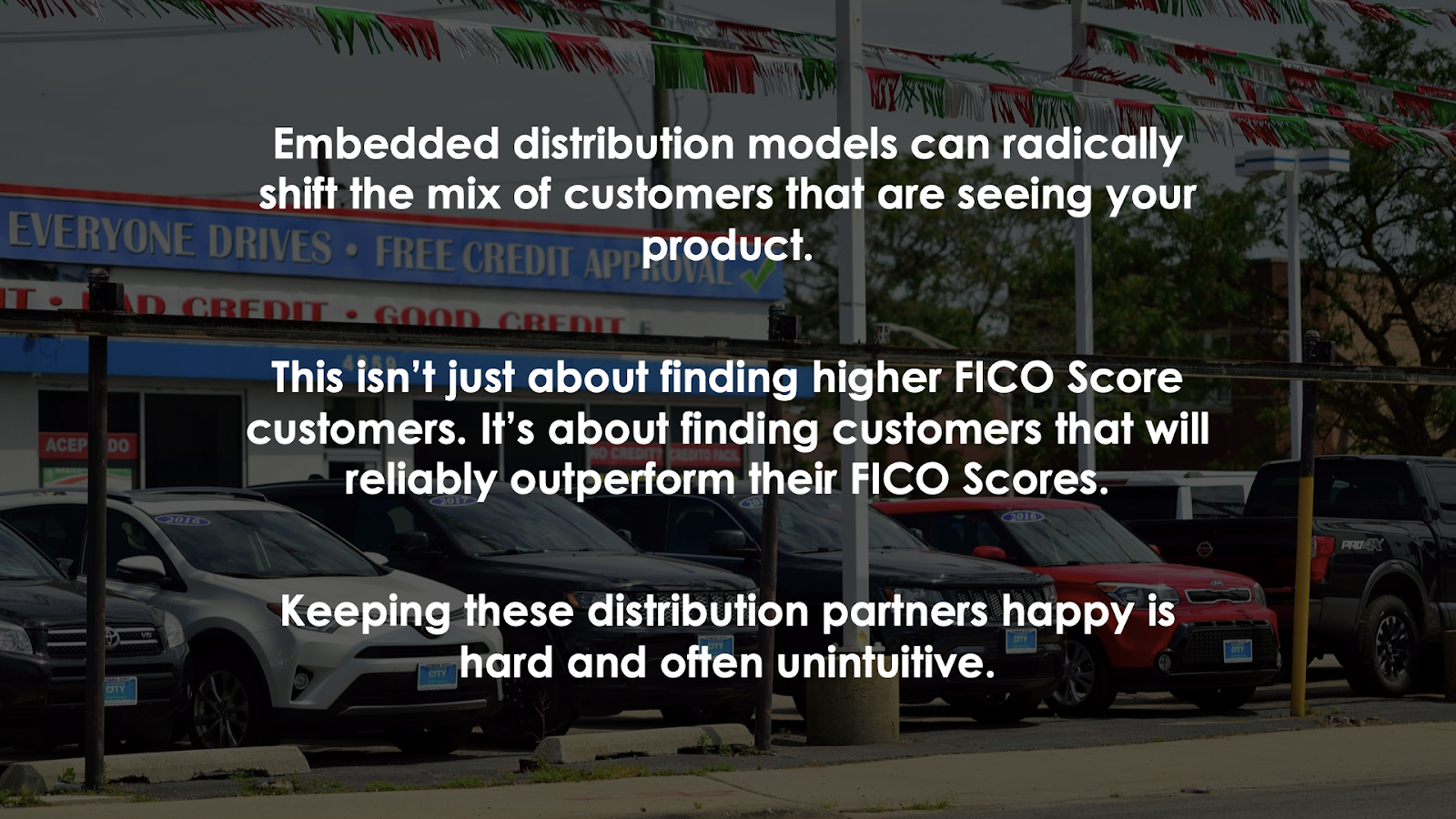

#6: Embedded Lending Can Drive Positive Selection

The winners in lending used to be those with the best branch proximity and loan officers in profitable geographies. Then things shifted, and the winners became those with the most sophisticated and effective underwriting models.

The next set of winners in lending will be those that have cultivated durable distribution partnerships with third parties that can drive positive selection for them.

Acquiring and keeping those distribution partnerships will require lenders to do stuff that might feel unnecessary or counterintuitive or embarrassing. They’ll need to get over it if they want to earn the right to win in embedded lending.

#7: New Platforms to Build Upon

A lot of value in financial services is wrapped up in the way that our infrastructure works. When we make something faster or safer, what we’re actually doing is taking on risk and being paid for it.

When the underlying infrastructure changes, a lot of value can shift very quickly.

There are two examples worth paying attention to:

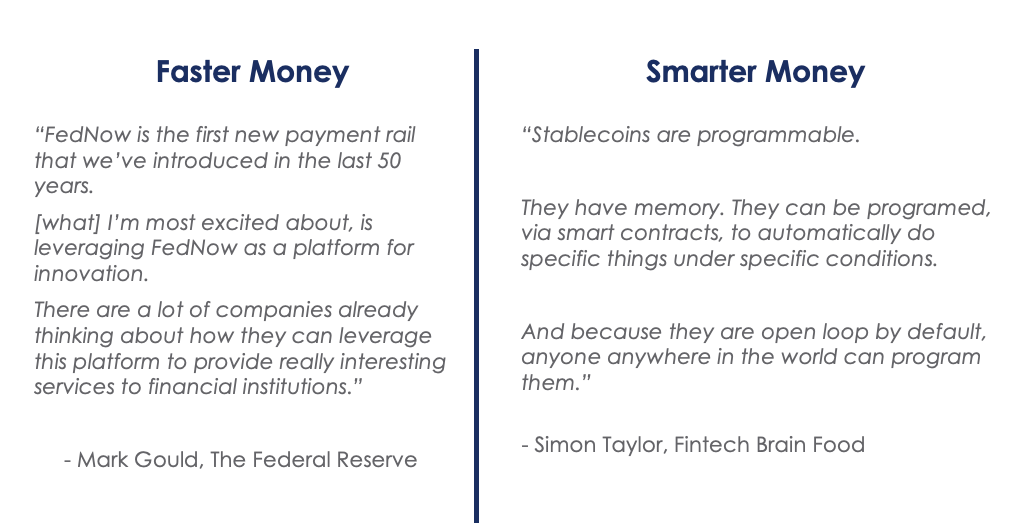

- Faster Money. Mark Gould, Chief Payments Executive at the Federal Reserve, told me and Jason Mikula that FedNow is being built to be a platform for innovation. The ACH system, which was built in the 70s, obviously wasn’t designed that way. This means that new solutions will be built very quickly once FedNow becomes ubiquitous, and a lot of the existing value that has been wrapped around the ACH system may be disrupted. An easy example – two-day early access to your paycheck will make no sense as a value prop five years from now.

- Smarter Money. I’m as skeptical about crypto as anyone, but my skepticism is mostly based on all of the speculation and nonsense that crypto’s volatility attracts. Stablecoins are crypto stripped of speculation. And as Simon Taylor explained to me on a recent podcast, what’s left behind is a transaction mechanism that is, by default, global, interoperable, and programmable. There are cool things we can do with that, especially when it comes to highly inefficient use cases like cross-border payments, trade finance, and B2B payments. This is why you see smart incumbents like Visa and PayPal continuing to build on stablecoins, even as the larger circus has moved on.

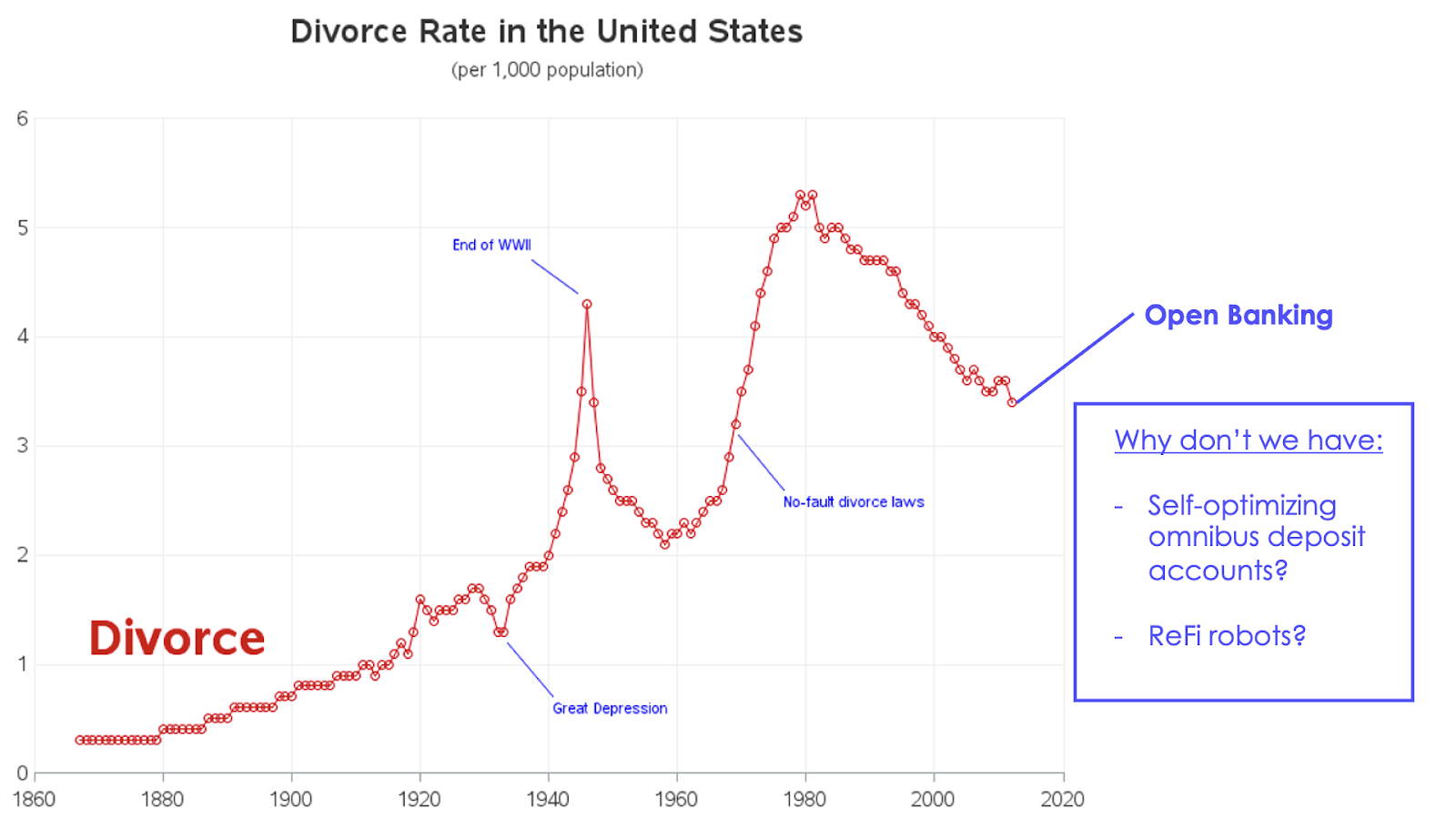

#8: The Era of No-Fault Divorces in Financial Services

It’s difficult to understand how satisfied and loyal your customers are when it’s expensive or time-consuming for customers to switch banks. When it becomes easier, you see exactly how much value you’ve been providing.

I think open banking is going to reveal exactly how much value banks have been providing to their customers.

The CFPB is explicitly designing its rules for open banking to enable much more seamless account switching. They want to make it push-button easy for people to break up with their banks.

I think it’s a little bit like the introduction of no-fault divorces in the U.S. in 1970.

It led to a spike in divorces immediately after, as people (mostly women) got out of bad relationships that they had been trapped in.

But then the divorce rate started to fall. And researchers who have studied marriage and divorce in the U.S. actually attribute the fall in the divorce rate partially to the introduction of no-fault divorces.

Why?

The spouse that was satisfied in the relationship and maybe taking their partner for granted had to suddenly work harder to make them happy. It helped make marriages better.

I think a similar thing may happen between consumers and their financial services providers.

We may see a spike in breakups in the short term, but long term, we’ll see more value being created as financial institutions have to continually earn their customers’ business.

#9: Open Banking + Generative AI

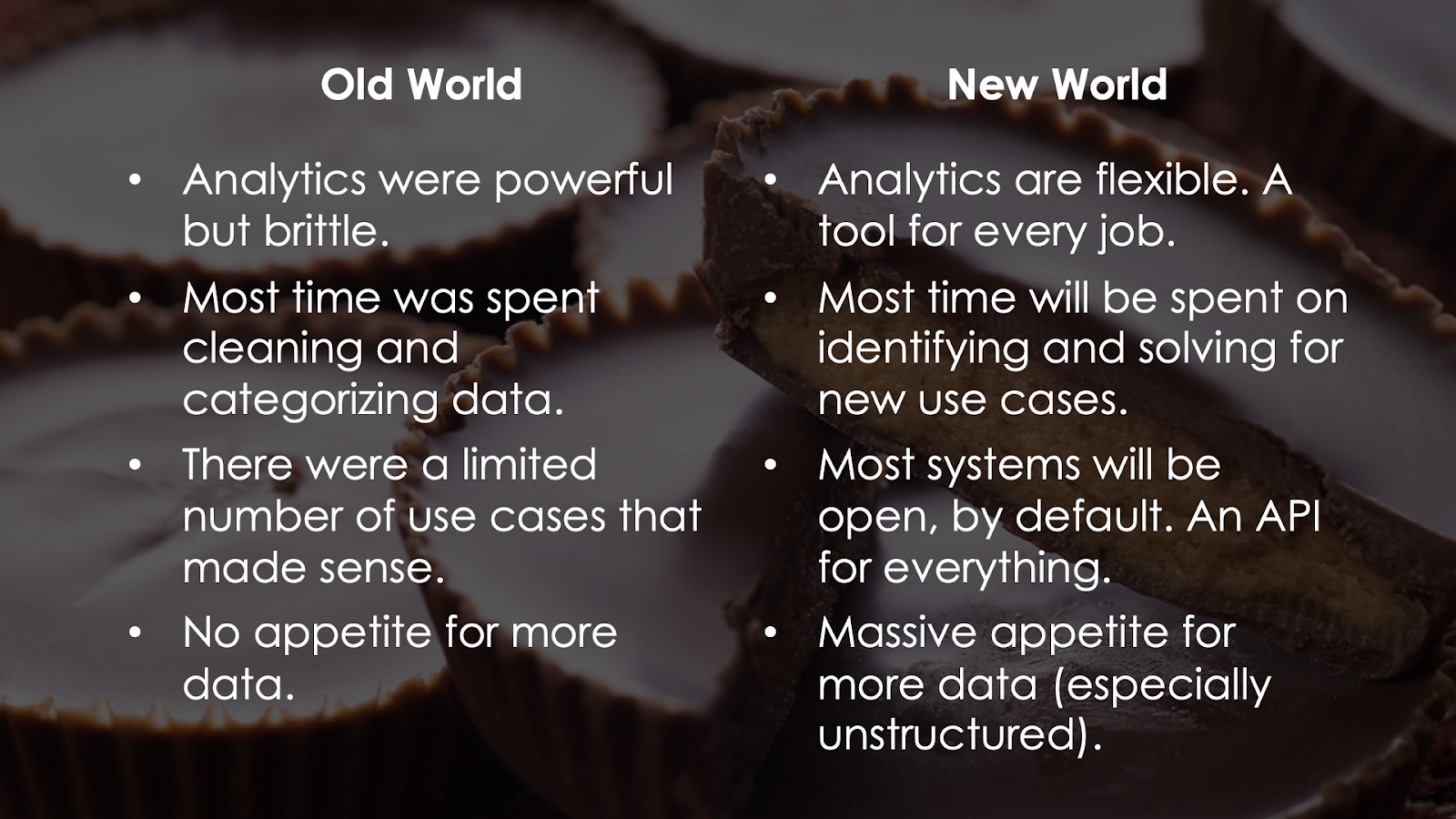

Banks have historically had a scarcity mindset when it comes to data.

You had to clean it, categorize it, and tee it up perfectly in order for your machine-learning algorithms to get anything useful out of it. It was like magic. You spent two days setting up the stage and the props in order to get five minutes of magic for the audience. Not really worth it unless it’s David Copperfield.

And because it’s not really worth it, outside of a couple of well-developed areas like credit risk analysis, most of the data that banks have just sits in data warehouses without ever really being used.

Generative AI has the potential to shake things up. Not because it’s better than the machine learning algorithms and other analytic tools and techniques that banks use today (it’s not). But rather because large language models (LLMs) are really good at things that traditional ML/AI models suck at, like, for example, efficiently extracting value out of unstructured data.

The fact that generative AI is coming along just as we are in the midst of rewiring all of financial services to be open and API-accessible, by default, is interesting.

What can banks build in a world in which they can feed not only all of their data but all of the data that they can convince their customers to bring with them, into analytic models that are eager to learn from vast and messy sets of unstructured data?

I’m not sure, but I’m excited to find out!