Let’s talk about the mechanics of how digital consumer lending has evolved over the last couple of decades.

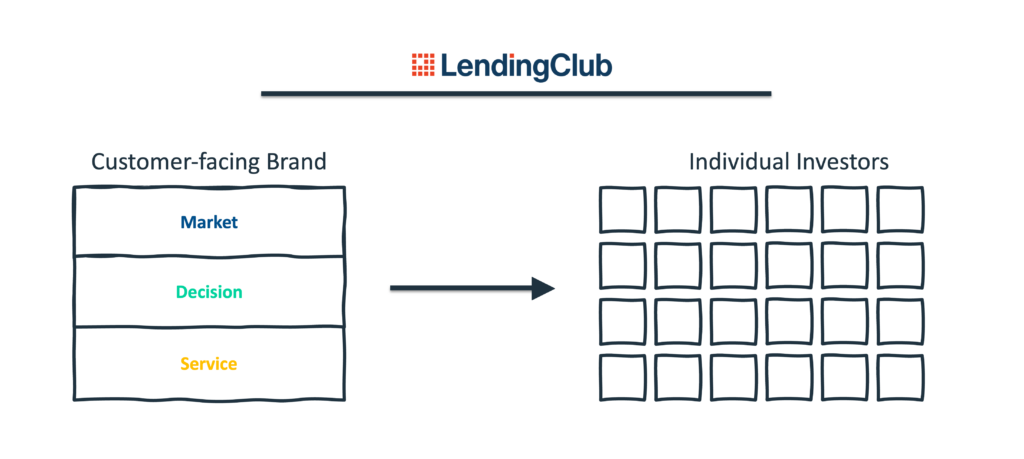

Twenty-ish years ago, Renaud LaPlanche and a few other clever folks figured out how to use the internet to facilitate a highly scalable and capital-light approach to lending by directly connecting borrowers and investors.

Person-to-person (P2P) lending was born.

P2P lending gave borrowers early exposure to the benefits of a digital-only lending experience, and it gave amateur and professional investors formative experience in evaluating and valuing unsecured loans as an asset class.

Over time, institutional investors (banks, insurance companies, pensions, sovereign wealth funds, etc.) became interested in digital loans, across a variety of product categories, as an asset class to invest in. They began to displace individual investors as the buyers of loans generated through digital lending platforms.

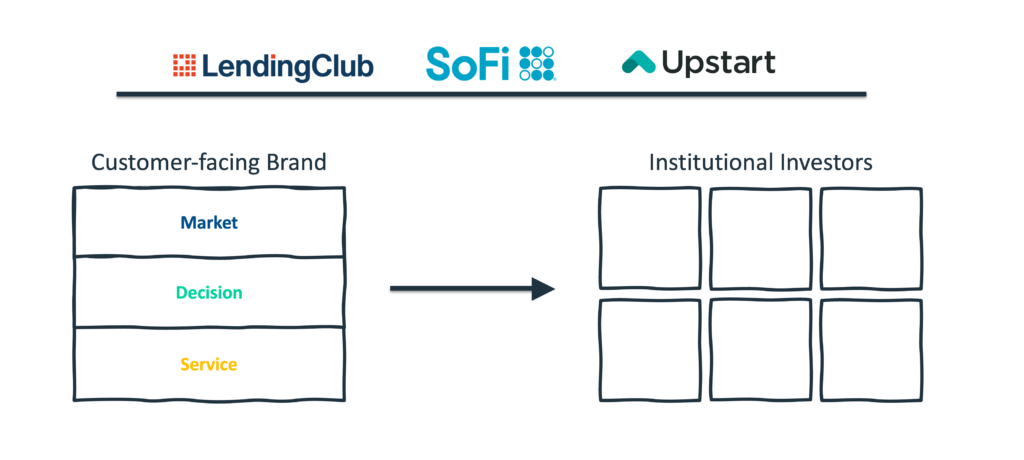

This trend accelerated significantly in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, as interest rates entered a prolonged near-zero period (motivating investors to search more aggressively for yield) and new regulations imposed far harsher capital requirements on banks (motivating them to pull back from both originating and funding many consumer and small business lending products).

New digital lending platforms like SoFi and Upstart entered the market, skipping directly to this originate-and-sell-to-institutional-investors model.

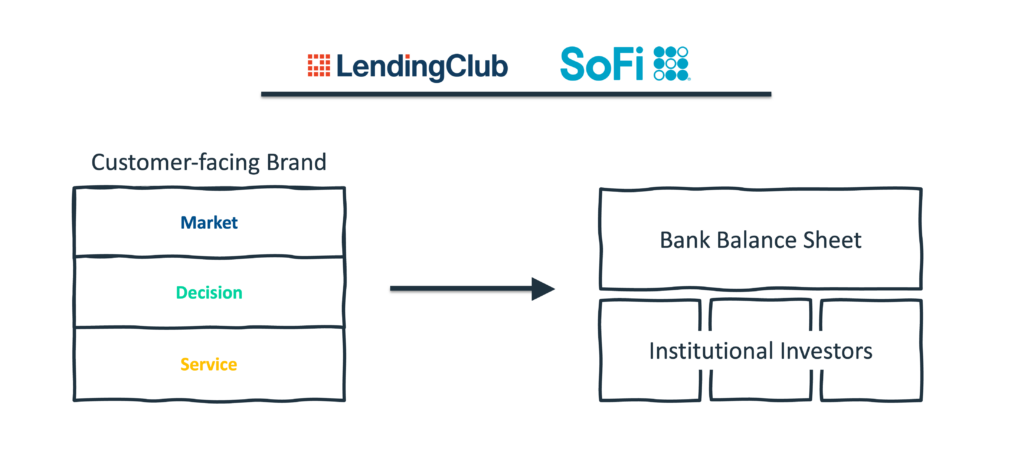

Recognizing that the good times couldn’t last forever and that the combination of higher interest rates and higher loss rates would wipe them out, a few forward-thinking online lenders aggressively pursued bank charters (through acquisitions of community banks). This vertical integration enabled these lenders to attain stable, low-cost funding (deposits), while still retaining their hard-won expertise in loan securitization and relationships with institutional investors (which they could lean on to supplement their balance sheet lending, as needed).

This proved to be prescient, as the Fed aggressively raised interest rates to combat inflation (though fiscal stimulus and the general economic weirdness during the pandemic kept loss rates under control).

And that brings us to today, where a few things are true:

- Consumer lending volumes and delinquencies are back up. According to the latest data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, total household debt rose by $212 billion to reach $17.5 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2023. Credit card balances increased by $50 billion to $1.13 trillion over the quarter, while mortgage balances rose by $112 billion to $12.25 trillion. Auto loan balances rose by $12 billion to $1.61 trillion, continuing an upward trajectory seen since 2011. Aggregate delinquency rates increased in Q4 2023, with 3.1% of outstanding debt in some stage of delinquency at the end of December. Delinquency transition rates increased for all debt types, except for student loans.

- Private credit is surging. Private credit – loans made to private companies by investors – has been booming ever since the government instituted more stringent capital requirements for banks in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis. The market is now $1.7 trillion in size (up from $300 billion in 2010), and it is projected to continue growing aggressively. Asset-based finance – loans made to lenders that pledge their receivables or other assets as collateral – is expected to be a significant driver of that growth.

- Digital has become table stakes. Consumers have come to expect streamlined digital experiences for most lending products, and even the holdouts (mortgage and auto) are becoming incrementally more digitized. The first-mover advantage enjoyed by the LendingClubs and SoFis of the world has become significantly weakened.

- The window for acquiring a bank charter has closed. Between the drama in BaaS and the changes coming to bank merger evaluations, I think it’s fairly safe to say that the opportunity for non-bank lenders and other fintech companies to obtain bank charters through acquisitions is nearly non-existent (at least for the moment).

- The overall economy remains a mystery. 85% of economists predicted a recession in 2023. Instead, the U.S. had stronger growth than any major high-income country while also having lower inflation rates than Japan. Yet concern continues to abound (some economists are sure this year is going to be the year we get a recession … no, really!), and it seems distinctly possible that lower interest rates (which we should see, at least a bit, in 2024) will cause the economy, and consumer credit more specifically, to overheat.

Given all of that, the question I’m interested in is – What will the next phase of the evolution of digital consumer lending look like?

I don’t know for sure, but I’m guessing that a company called Pagaya will be in the middle of it.

What’s a Pagaya?

If you haven’t heard of Pagaya, don’t feel bad. Until a few months ago, I hadn’t either.

If you’ve heard of Pagaya, but you don’t really understand what the company does, don’t feel bad. I spent a solid hour consuming the marketing fluff on the company’s website and couldn’t make heads or tails of it.

Pagaya is difficult to understand. However, it’s also one of the most interesting companies in the consumer lending space, and I think its product and business model tell us a lot about where the space is headed.

So let’s talk about Pagaya!

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

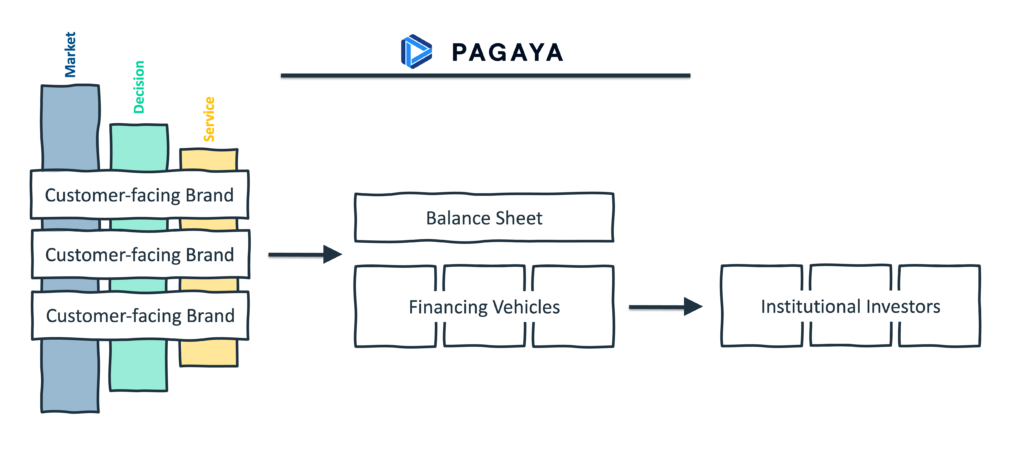

The company was founded in 2018. It got its start as an asset management firm focused on consumer lending. However, it has evolved into something much more unique – an embedded second-look lending network.

Second-look lending isn’t a new concept. The basic idea is that instead of rejecting an applicant for a loan because they don’t fit your credit box or you are unable to get sufficient data to decision them, you can pass them off to a different lender who might be able to approve them. Traditionally, this experience has been clunky and more than a little embarrassing for applicants (we can’t approve you because we’re too good for you, but these guys have lower standards).

Pagaya’s innovation is to integrate directly within the lender’s digital origination workflow. When an applicant is rejected by the lender’s decision engine, they (and all of their data) can be instantly passed to the Pagaya decision engine to see if it can approve them. If it can, the lender books the loan, sells the paper to Pagaya, and retains the servicing relationship with the customer.

The front-end experience is seamless. Whether the customer is approved by the lender or by Pagaya behind the scenes, it feels to them like the lender said yes. They download the lender’s mobile app, make payments, and contact them if they have any problems. They never see or feel Pagaya’s presence at all.

To fund this activity, Pagaya arranges pre-funded commitments (“financing vehicles”) to buy the loans from the lenders and securitize them. These financing vehicles are funded by a network of yield-hungry institutional investors, most notably sovereign wealth funds like Singapore’s GIC (which is also a major equity investor in Pagaya). The company also keeps a small portion of loans on its own balance sheet (which was just fortified by a $280 million credit facility led by BlackRock and JPMorgan Chase).

At the end of 2023, Pagaya had 29 lending partners in its lending network and 109 investment firms in its funding network. The company facilitated $2.4 billion in lending through its network in 2023, a 33% year-over-year increase. In total, Pagaya has generated roughly $20 billion in new lending since its inception in 2018.

Most of that volume has been created through unsecured personal loans, which is the market that the company started in. Pagaya works with most of the big non-bank personal loan providers (Prosper, Avant, SoFi … which I know, they’re a bank now) and, increasingly, big banks (they recently signed up U.S. Bank).

The company has also made significant headway in indirect auto (Ally, Exeter Finance, Westlake Financial) and point-of-sale lending (Pagaya is the funding source for approximately 10% of Klarna’s interest-bearing POS loans in the U.S., and the company unsuccessfully tried to acquire GreenSky from Goldman Sachs, despite offering Goldman $200 million more than the bidder that Goldman ended up selling to).

Pagaya is also working on cracking the credit card market (which poses some unique servicing and risk management challenges), and it has, bizarrely, also gotten into real estate investing (single-family rentals, specifically) through its acquisition of Darwin Homes last year.

You may be wondering, what gives Pagaya the confidence to approve and acquire loans, across a number of different product categories, that the lenders generating those loans don’t want (as well as to invest in single-family rental properties)?

AI!

The company talks A LOT about AI, the sophistication of its underwriting models, the size and expertise of its data science team, and the vast treasure trove of training data that it has access to through its lending network:

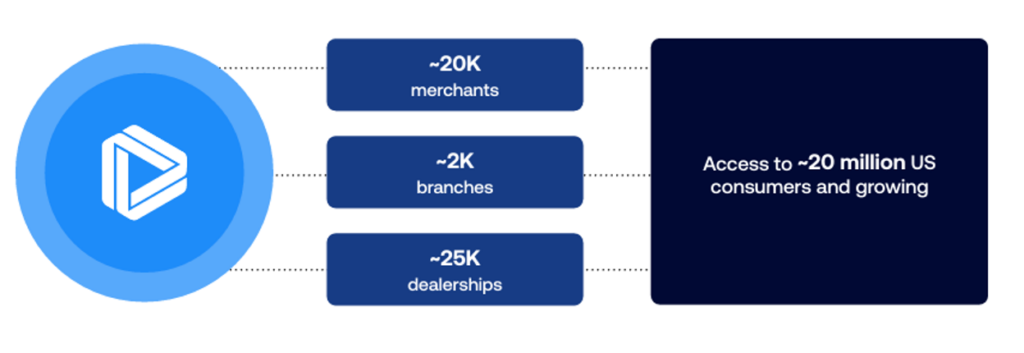

We are now integrated with 29 different lenders, connecting us to approximately 20,000 merchants, 2,000 branches, 25,000 unique auto dealerships, and 20 million U.S. consumers.2 This cross-lender, cross-asset data set gives us a tremendous underwriting advantage over traditional systems

It’s a well-timed story, given the market’s appetite for anything even tangentially related to AI. But are investors buying it from Pagaya?

That’s a complicated question!

Between 2018 and 2022, Pagaya raised more than $145 million in equity financing from VCs. In June of 2022, the company went public at an $8.5 billion valuation via a SPAC merger. The results since then haven’t been great.

After hitting a post-SPAC high of $297 per share (good for a $20 billion market cap) in July of 2022, Pagaya’s stock price collapsed to a low of $7, where it has been hovering (with a few brief rallies) ever since.

What’s the stock market’s problem with Pagaya?

Maybe it’s an allergic reaction to the company going public via a SPAC. Maybe Pagaya’s type of AI isn’t the type of AI that the market is looking to invest in. Maybe the market is concerned about broader macroeconomic forces dragging down Pagaya’s business model (if we ever get that recession we were promised). Or maybe, as I have written before, stock market analysts don’t know what the fuck they’re doing, and they have failed to appreciate the value of what the company has built (to be fair, it is a challenge just to understand the basics of what the company does!)

I can’t say exactly what the market thinks about Pagaya’s current performance or future potential.

However, I can say what I think.

(Editor’s Note – My eternal reminder: nothing I ever write or say is investment advice!)

My Take

Looking at the immediate future, it seems to me that Pagaya has some room to run.

On the lending network side, the notion of expanding a lender’s credit box — to either approve riskier applicants or better price premium ones (or to enable a lender to enter an entirely new market without taking any credit risk at all) — with zero incremental UX friction is a very attractive pitch. It improves the ROI on lenders’ customer acquisition investments and gives them the opportunity to build and expand relationships with more customers and partners.

Clearly, the value proposition is resonating with lenders, and Pagaya figuring out how to cross the chasm from selling to fintech companies to selling to banks is a big deal. U.S. Bank is a big get. Banks love to be the second or third customer, never the first.

It also seems likely that Pagaya will find ways to move into other parts of the lending lifecycle, to further optimize results for their lender and investor partners.

My understanding is that Pagaya has already moved up the customer acquisition funnel, integrating directly with lead aggregators like Credit Karma, to help ensure that their lending partners capture as many new customer relationships as possible.

I would guess that Pagaya is going to push down the lifecycle as well, moving more into loan servicing and collections. They obviously won’t disintermediate their lending partners from their customers (that would be counter to Pagaya’s model), but they do have a vested interest in gaining more visibility into (and possibly control over) this part of the lifecycle. Klarna is a good example of why. If Klarna doesn’t retain any of the risk for a portion of the POS loans made through its U.S. merchant partners, then it has very little incentive to employ collections tactics that would cause those customers (or the merchants they shop with) to be upset. Pagaya (and its investors), on the other hand, might want to see Klarna be a little more assertive in trying to get those delinquent customers back on track. Figuring out how to resolve this inherent tension will, I imagine, be a big priority for Pagaya moving forward.

On the funding network side, I guess things will just keep growing?!?

Despite having done quite a bit of research and writing on the private credit space (read this essay for a much deeper dive). I still don’t really understand it. Why are investors, including those at the largest and most sophisticated asset management firms in the world, so bullish on private credit generally, and asset-based finance specifically? How has private credit continued to grow so quickly, even as we’ve transitioned from a low-rate environment to a high-rate environment?

I don’t know! But everyone in the space seems very optimistic, which likely bodes well for Pagaya being able to attract additional investment firms to its funding network.

That’s my short-term view.

Over the longer term, I am concerned.

Pagaya describes its model as one that decouples the relationship (between the lender and the customer) from the asset (the loan receivables).

That’s a good way to frame it. From a 30,000-foot view, you can think of that model as the natural end state for the increasingly fractured and highly specialized consumer lending ecosystem that we’ve built.

Lenders on the front end, saying yes to everyone. Investors on the back end, saying yes to everything. And a risk management and pricing engine in the middle, matching up supply and demand and getting exponentially smarter as you run more volume through it.

It makes the idea of a single institution sourcing capital, acquiring customers, originating and servicing loans, and keeping them on their balance sheet (i.e. a bank) seem rather quaint, by comparison.

Having said that, something about Pagaya’s model feels risky to me. Existentially risky.

When you decouple the relationship from the asset, you introduce a greater appetite for risk on both fronts. Lenders market their products more widely and aggressively than they would if they were forced to retain the risk, and investors take on more risk than they would if they were forced to spend the time and money to acquire and underwrite the assets themselves. We saw exactly how this story ends in 2007 (albeit at a much larger scale), and when I look at a sector like auto lending (in which all the warning signs are already flashing bright red), I worry about a repeat.

For all of its drawbacks, the discipline required to run a full-stack lending business helps to modulate the risks taken at every level of the stack.

That’s not something you can replace with AI.