One of the most challenging things about working in fintech is trying to figure out which lessons to take from the world of financial services (the “fin”) and which lessons to take from the world of software (the “tech”).

The reason this is challenging is that financial services and software are very different industries. On a fundamental level, they don’t work the same way. And that makes combining them together tricky.

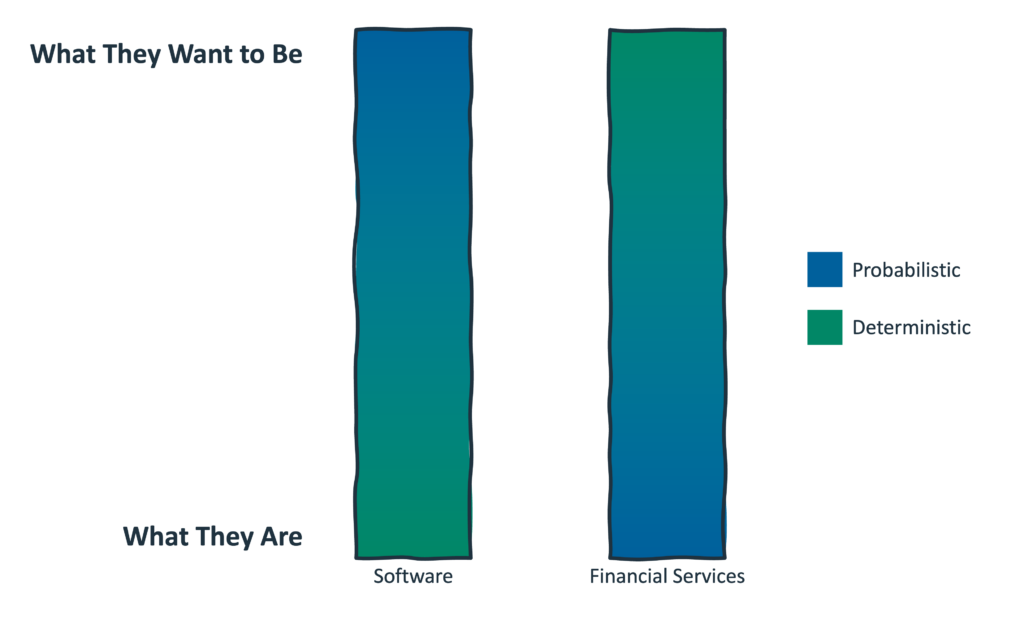

One way to understand this challenge is to think about the difference between deterministic systems and probabilistic systems.

A deterministic system is one where, if you know the specific set of initial conditions and inputs, the system’s outputs and future state can be perfectly predicted with no element of randomness involved.

By contrast, a probabilistic system is one in which the outcome of events cannot be perfectly predicted, even if all the inputs and initial conditions are known. Instead, it relies on probabilities to describe the likelihood of different potential outcomes.

Software is a deterministic business. You build a system that transforms a consistent set of inputs into a consistent and predictable set of outputs within a finite and well-understood set of use cases. Your revenue is (likely) generated through fees paid by your customers (subscriptions are a very common business model), and those fees don’t require additional and incremental risk-taking to earn each additional dollar of revenue. You just build the product, spend money to acquire customers, and then watch the magic of zero marginal costs do its thing. Or, as my dad is fond of saying, “The first transaction costs you $20 million. The rest of them are free.”

Now, of course, that’s not exactly true. Software companies carry ongoing expenses, including product maintenance and customer support. However, it is directionally true to say that software businesses, when they work, are highly deterministic and highly profitable when operated at scale.

Banking is the opposite.

Banking is a probabilistic business because it’s built on risk. If you are lending money, you are placing a bet on every single customer. You are betting that they are who they say they are, that you are legally allowed to work with them (now and in the future), and that they have the willingness and ability to repay (now and in the future). The marginal cost of adding additional customers isn’t zero. In fact, growth usually requires you to take on more risk.

Software is a naturally deterministic business, while banking is a naturally probabilistic one.

What’s interesting, though, is how much time and money software companies and banks spend trying to change their essential natures.

The baseline for a software business is deterministic. However, the upside for a software business often lies in its ability to generate probabilistic outcomes.

Social networks are a good example. The function of TikTok is deterministic — you upload a video, and it is shared with your followers and (if you choose) algorithmically across all TikTok users — but the behavior of users on TikTok is highly probabilistic. I still can’t tell you what this year’s “brat summer” was, but I guarantee you that the creators of TikTok didn’t design it and couldn’t have predicted it. TikTok trends are an emergent property of the platform and a source of much of the value that it creates, which is why every other social network has been furiously trying to copy TikTok’s probabilistic product and UX design.

It’s also why VC investors are so excited about generative AI:

One remarkable thing about the invention of generative AI is that it’s one of the first examples of a probabilistic computer that produces outputs that are varied and non-deterministic. Some, who expect these systems to behave like traditional systems, have complained about hallucinations — however, these complaints miss the point. A dispersion of outputs (including hallucinations) is exactly what’s so special here. In fact, they unlock a whole new category of product design: probabilistic products.

On the other hand, while the baseline for a bank is probabilistic, the upside lies in its ability to generate more deterministic outcomes.

This desire for more deterministic outcomes drives banks to focus heavily on risk management across every aspect of their business, from credit risk underwriting to operational contingency planning. Everything that a well-run bank does revolves around making risk less chaotic and more predictable.

This is also why financial services regulators are nervous about generative AI, especially for customer-facing use cases. They want fewer and less severe probabilistic outcomes.

The inherent challenge in fintech — in which we are melding together software and financial services into something fundamentally new — is figuring out how to balance the tensions between deterministic and probabilistic business models and product ambitions.

Indeed, much of the last decade of fintech in the U.S. has been defined by our failure, as an industry, to strike the exact right balance.

We’re Not a Bank. We’re a Software Company.

If you were working in fintech in 2021, you might remember a popular narrative among later-stage fintech companies that were positioning themselves to public market investors as software companies rather than banks.

Here’s how Chime CEO Chris Britt described his company after raising $485 million at a $14.5 billion valuation:

We’re more like a consumer software company than a bank. It’s more a transaction-based, processing-based business model that is highly predicable, highly recurring and highly profitable.

And here’s a slide from a presentation that SoFi prepared for investors before going public via a SPAC, comparing its winner-take-most opportunity to other famous SaaS businesses:

The reason these companies attempted to position themselves as software companies is simple — investors value the predictable and low-risk nature of software revenues and routinely reward software companies with valuations that far outstrip their revenues.

The trouble is that this wasn’t just a talking point for many fintech companies in 2021. They actually believed they were software companies, not financial services companies.

That belief led them to make some very bad decisions, which we’re still paying the price for today.

An Imbalance in Supply and Demand

Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) is the technical, legal, and operational integration between chartered banks and non-bank companies. It allows non-bank companies to offer financial products and services to their end customers.

One of the best ways to understand BaaS is to think in terms of supply and demand.

Supply comes from the banks, of which there are roughly 4,500 in the U.S.

Demand comes from non-bank companies, which include both B2C and B2B fintech companies, as well as platforms, software companies, and other businesses operating outside of financial services interested in embedding financial services into their products.

Supply and demand in BaaS are not constant. As in every market, they wax and wane according to many different macro and industry-specific factors, which has a dramatic effect on the leverage that buyers and suppliers have over each other.

In 2021, demand for BaaS was incredibly strong. One out of five dollars raised from VCs globally that year were invested into fintech companies. Many of those fintech companies needed bank partners to operate.

However, while the demand to buy BaaS was strong in 2021, the desperation to supply it was even stronger. Community banks, eager to find a path towards profitable organic growth, jumped into the space in droves, encouraged and enabled by a new class of middleware platforms, which promised to make BaaS push-button easy.

This imbalance between supply and demand led to fintech companies (and BaaS middleware platforms) having significantly more leverage than banks when it came time to negotiate.

And this is where fintech companies’ belief that they were software companies, not financial services companies, got them into trouble.

“Winning” The Negotiation

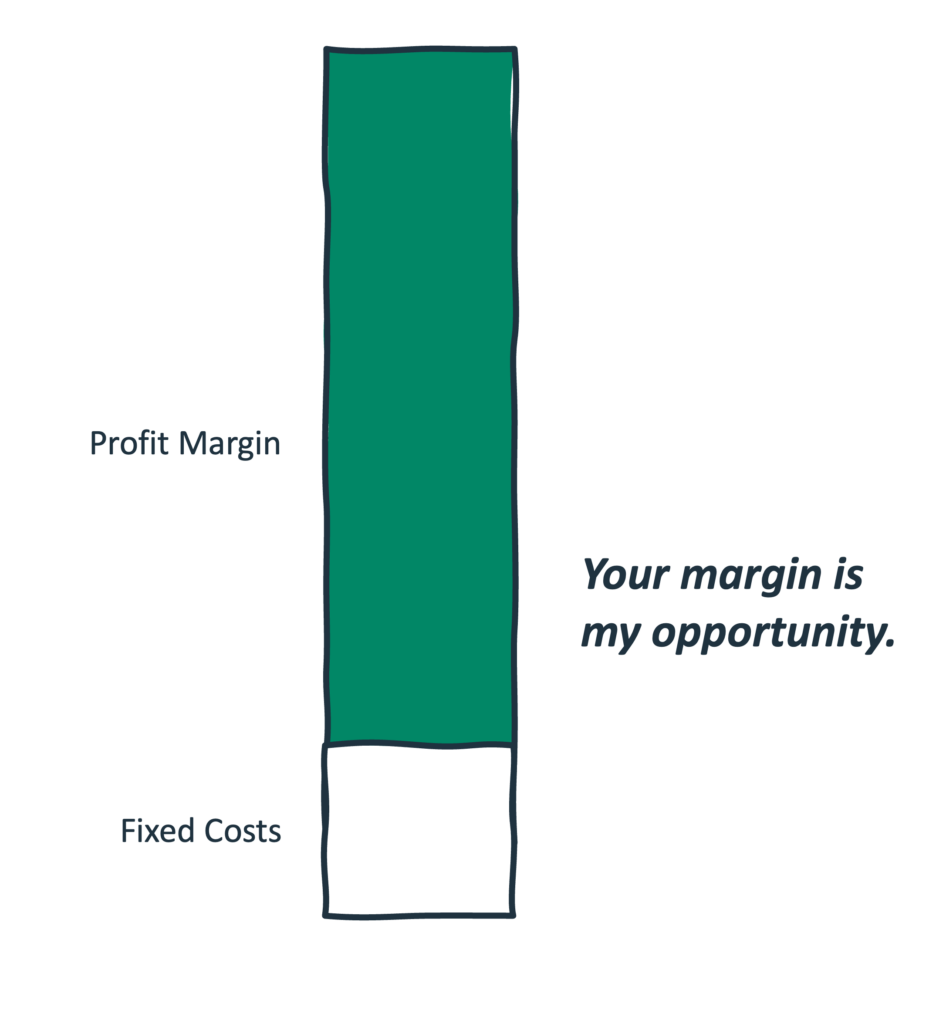

When software companies negotiate with each other, the assumption is that there’s little to no risk in negotiating too hard.

After all, software companies operate highly deterministic businesses that reliably generate revenue and a very healthy profit margin at scale. If one company has more leverage in the negotiation and squeezes its counterparty a bit, it’s not a huge deal. The other party can afford it.

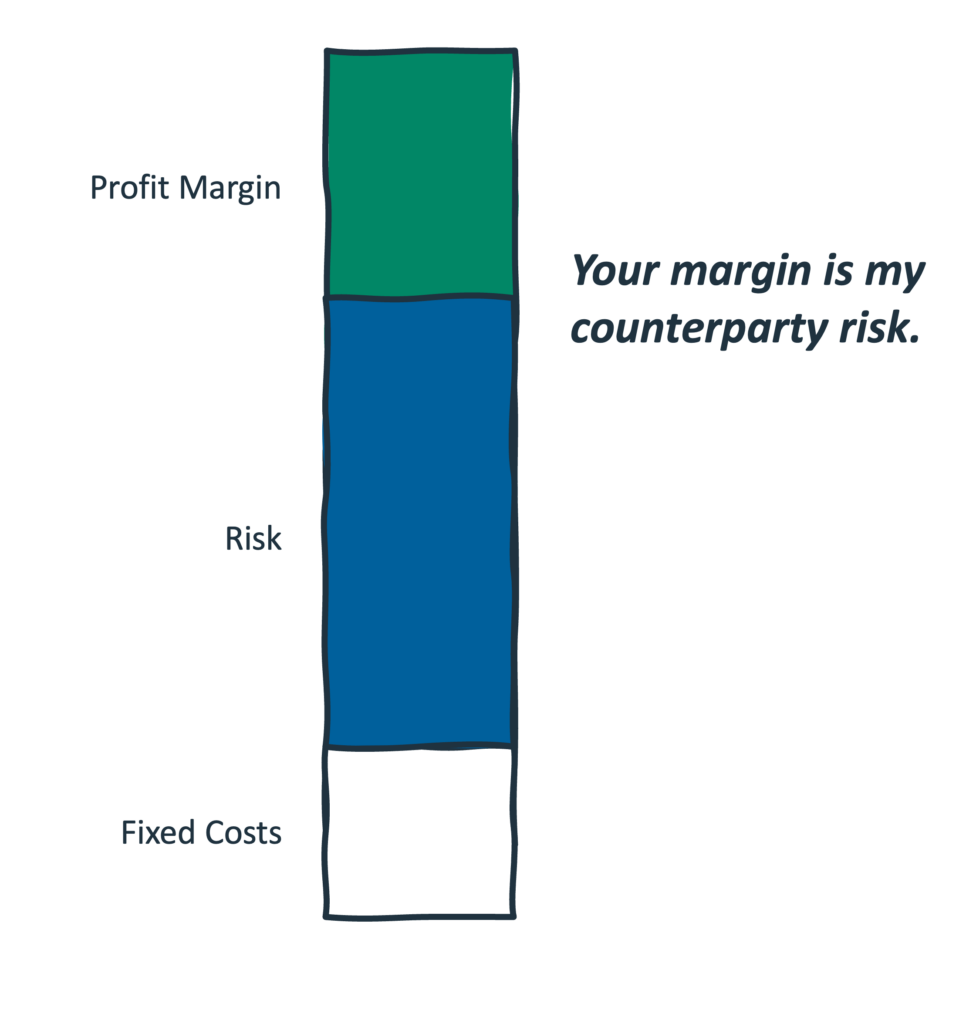

However, this is a very dangerous assumption to take into a negotiation with a bank partner because that partner’s business is probabilistic.

“Winning” the negotiation with them might mean pushing them to take on excessive amounts of risk, which, as their counterparty, can create a very serious problem for you.

This dynamic has wreaked havoc in the banking-as-a-service space over the last 18-24 months.

Fintech companies approached negotiations with potential bank partners with the same intent they took into all their other vendor negotiations: to extract the best possible economic terms and ensure that their software engineers had the maximum amount of flexibility and control to build great products.

And banks, seeing BaaS as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to grow, became undisciplined in managing their inherently probabilistic businesses and took on too much risk to win the deals.

An excellent example of this, on the economics side, is Goldman Sachs, which “won” the Apple Card deal in 2019 by agreeing to terms that none of the other (much more experienced) co-brand credit card issuers were willing to agree to (the old adage “if you can’t find the fish at the poker table, it’s likely you are the fish” is very applicable here).

Those terms included an aggressive underwriting strategy (Apple wanted to say yes to as many customers as possible), no fees, and limited risk sharing. And the result, predictably, was that Goldman Sachs lost a ton of money on the card, according to analysis from Flagship Advisory Partners:

The combination of a substantial portion of Goldman’s clientele holding a FICO score below 660 coupled with the absence of late fees, forms a potent catalyst for impacting Goldman’s earnings—and it did. Flagship estimates that Goldman will incur a pre-tax loss on the Apple Card program of approximately $500 million in Q4 2022 – Q3 2023.

This was obviously unsustainable for Goldman Sachs, which led to the bank’s decision to cut its losses on all its consumer banking and embedded finance ventures, including the Apple Card, which it is trying to offload to a different issuer.

However, Goldman will likely need to pay money to get away from the Apple Card, as no issuer is reportedly willing to pay face value for the $17 billion in receivables that come with the program. In fact, Wells Fargo analyst Mike Mayo estimates that it could cost Goldman Sachs between $500 million and $4 billion just to dump the Apple Card.

While this type of risk-taking is reasonably apparent and straightforward to quantify (and thus easy for other banks to avoid), we have also seen subtler but still highly dangerous forms of risk-taking in BaaS.

An illustrative example of this is Mercury and Evolve Bank & Trust.

As Jason Mikula reported in Fintech Business Weekly, Mercury (a neobank for startups and other small businesses) routinely used its leverage with its banking partner Evolve to facilitate its growth goals, with little regard for compliance. Indeed, Mercury was so aggressive in its growth-over-everything strategy, and Evolve was so permissive in its approach to compliance that Mercury would periodically go around its BaaS middleware platform Synapse (which, as we know from Mr. Mikula’s extensive reporting, wasn’t a paragon of good compliance and risk management itself) to get what it wanted:

In some cases, when Synapse wouldn’t meet Mercury’s demands, the company would escalate them directly to Evolve, the former employee said. For example, Synapse had concerns about higher-risk jurisdictions, like Turkey, or those with sanctions in place, like Russia.

But Mercury wanted to facilitate users and transactions in those countries, and, when Synapse wasn’t sufficiently cooperative, Mercury sought Evolve’s signoff on adding certain users to a so-called “whitelist,” former Synapse staffers said. Being added to the whitelist would enable those accountholders to make transactions in amounts and with counterparties that they otherwise would not be able to make.

This regulatory compliance risk-taking (which went well beyond Mercury) eventually resulted in Evolve receiving the most wide-ranging regulatory enforcement action that I’ve seen in the BaaS space, which included third-party audits and evaluations of Evolve’s risk management systems and processes, significant required investments in those same systems and processes, and stringent restrictions on Evolve’s ability to bring on new fintech partners or launch new products or services with existing partners.

Critically, this excessive risk-taking didn’t just negatively impact Goldman Sachs and Evolve Bank & Trust. It impacted their partners as well.

Apple’s ability to iterate on and improve the Apple Card has been hamstrung for years now because Goldman’s heart (and, more importantly, wallet) hasn’t been in consumer banking or embedded finance. And it’s not like the situation is going to markedly improve once a new issuer steps in, as Flagship Advisory Partners astutely points out:

Apple can likely be certain that future potential partners will have learned from Goldman’s lessons, and we speculate that the next deal that Apple gets will be worse than if it had struck a more balanced deal with Goldman.

Mercury is in a similar boat. It can’t launch new banking products or services through Evolve without getting a non-objection from Evolve’s regulators first (and I’m guessing that would be a tough sell right now), and it will be incredibly difficult for Mercury to move to a new bank partner because that bank will (justifiably) have very little confidence in Mercury and Evolve’s KYC/KYB and AML processes and will likely require a comprehensive re-evaluation of all of their customers.

These were painful lessons for these specific companies, but more importantly, they helped push the industry toward a critical inflection point.

Regulators Change the Game

Regulators had been ramping up their supervision and enforcement in BaaS for quite a while before the Synapse meltdown, but post-Synapse, they kicked it into overdrive.

I’ve written extensively about the regulatory response to Synapse, so I won’t rehash all of that in this essay. I just want to point out two specific outcomes from this increased regulatory attention.

First, regulators are finally acknowledging the impact that unequal power dynamics between banks and fintech companies can have on banks’ ability to manage risk and meet all of their operational and compliance responsibilities.

A few months back, the OCC, Federal Reserve, and FDIC released a Request for Information on Bank-Fintech Arrangements Involving Banking Products and Services Distributed to Consumers and Businesses, which, among other things, acknowledged that banks’ relationships with fintech partners are fundamentally different from traditional bank technology vendors:

These facets of bank-fintech arrangements may create heightened or novel risks for banks relative to the risks associated with more traditional third-party vendor relationships.

And asked how these risks might impact banks’ approach to contract negotiation and due diligence:

What impact, if any, does the size and negotiating power of the bank or the fintech company have on [contract negotiation and due diligence]? What impact, if any, does bank liquidity or revenues concentration represented by any particular fintech company, intermediary platform provider, or business line have on [contract negotiation and due diligence]?

Second, regulators are making it significantly more expensive for banks to supply banking-as-a-service capabilities to fintech companies and non-bank brands. This change has happened directly (via mechanisms like the FDIC’s brokered deposits rule) and indirectly (via heightened expectations for how much BaaS banks must invest in compliance, particularly human compliance staff). This change (along with a pile of active consent orders for BaaS banks) has restricted the supply of banks that are willing and able to take on new fintech and other non-bank programs.

In summary, regulators have both acknowledged the dangers of banks’ lack of leverage in fintech partnership negotiations and introduced a series of structural changes and market incentives to shift the leverage back to the banks.

That’s a perfectly logical response to the recent challenges in BaaS, but my concern is that we’re setting ourselves up to experience those challenges all over again, only this time in reverse.

Banks Need to Not Overplay Their Hand

In the same way that fintech companies didn’t understand the risks of using their leverage to “win” their negotiations with bank partners, I worry about banks overusing their leverage now that the power dynamics in BaaS have shifted back in their favor.

It can be tempting, in the name of risk management, to try to impose as many deterministic systems and frameworks on fintech partners and prospective partners as possible.

However, it is critical to strike a balance here and not to cure the disease by killing the patient.

The probabilistic upside of fintech — its rapid, iterative approach to product development, its healthy disinterest in legacy business models and product structures — is what drives the value for bank partners and, more crucially, for end customers.

In doing the research for this essay, I heard several stories of BaaS banks overindulging their newfound leverage to impose unreasonable requirements on existing partners (re-KYC your entire program and submit every piece of marketing collateral to us within 30 days) and to force new partners to meet certain thresholds (you need to have $40M in ARR before we’ll talk to you) and accept standardized systems and product constructs with almost zero room for configuration or customization (here’s the product, you can pick the colors and the logo).

To be blunt, this approach isn’t going to work.

It may remove many of the risks, but it also eliminates the room for innovation.

With all due respect, we can’t allow fintech and embedded finance to devolve into co-brand credit cards 2.0.

The Path Forward

The RFI put out by the OCC, Fed, and FDIC uses the term “bank-fintech arrangements” rather than “bank-fintech partnerships.” I don’t think that’s an accident. While everyone loves to use the term “partnerships” to describe their working relationships with critical third parties, they almost never are true partnerships.

This will need to change if we want BaaS and embedded finance to thrive in the future.

Software companies and banks will need to make their counterparties’ best interests a contractual priority, regardless of the leverage they have (or don’t have) in the negotiation.

Software companies will need to build as close to the metal as possible in order to maximize the available profit margin that can be shared with their bank partners.

Banks will need to build technology platforms that can deliver scale and efficiency without forcing software companies to over-standardize on rigid product constructs and operating models.

It won’t be easy. No one will feel like they’re winning, but that’s actually what building fair and sustainable partnerships requires.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Fifth Third Bank.