Here’s a question I am obsessed with — How can we ensure that banks and credit unions survive?

On its face, this obsession might strike you as odd. I write about fintech, which, if we apply the transitive property of content creation, also means that I write about disruption. Why, you might ask, should someone who writes about (and frequently celebrates) disruption care about the fate of the companies being disrupted? Doesn’t the mere fact that they are being disrupted mean they deserve it?

Well, yes, but it’s more complicated than that.

Banks and credit unions are systematically important to our economy.

However, the business model of banking is breaking down. If banks and credit unions don’t figure out a new and sustainable alternative, the consolidation we’ve been seeing in the industry will continue, or even accelerate.

So, the purpose of today’s essay is to explain why banks and credit unions are essential to our economy, why the core business model of banking is in structural decline, and how banks and credit unions can rebuild that business model into something more durable and better aligned with the long-term interests of their customers and members.

(Editor’s Note — Throughout most of the remainder of this essay, I will use the term “bank” as shorthand for any regulated financial institution that takes deposits and makes loans. It’s too cumbersome to keep writing “and credit unions.”)

Why Banks Matter

Steve Randy Waldman’s influential article Why is finance so complex? makes a compelling case that banks are fundamentally necessary for modern economies because they obscure risk. Banks perform the essential task of pooling savings and managing credit risk, thereby fostering economic growth. Waldman writes:

A banking system is a superposition of fraud and genius that interposes itself between investors and entrepreneurs…Banks guarantee all investors a return better than hoarding, and they offer this return unconditionally.

This opacity isn’t accidental — it’s a core feature. Banks thrive by projecting stability, guaranteeing savers steady returns, and deploying pooled funds into productive, albeit risky ventures through commercial and consumer loans. Without this collective willingness to bear hidden risk, widespread economic growth and investment would stall. Here’s Waldman again:

Financial systems help us overcome a collective action problem. In a world of investment projects whose costs and risks are perfectly transparent, most individuals would be frightened. Real enterprise is very risky. Further, the probability of success of any one project depends upon the degree to which other projects are simultaneously underway. A budding industrialist in an agrarian society who tries to build a car factory will fail. Her peers will be unable to supply the inputs required to make the thing work. If by some miracle she gets the factory up and running, her customer-base of low capital, low productivity farm workers will be unable to afford the end product.

Put simply, the task of maturity transformation — borrowing short to lend long — which is the core job that society requires banks to do, depends on banks’ customers not looking too closely at the risks they are taking.

What’s interesting is that, historically, banks’ ability to make money has also depended on their customers not looking too closely … at the prices they were paying (and being paid).

Net Interest Margin

Net interest margin (NIM) is the difference between the interest banks earn from lending and other investments and the interest they pay to borrow money (principally through customer deposits), expressed as a percentage of their interest-earning assets. Historically, NIM has been the backbone of bank profitability.

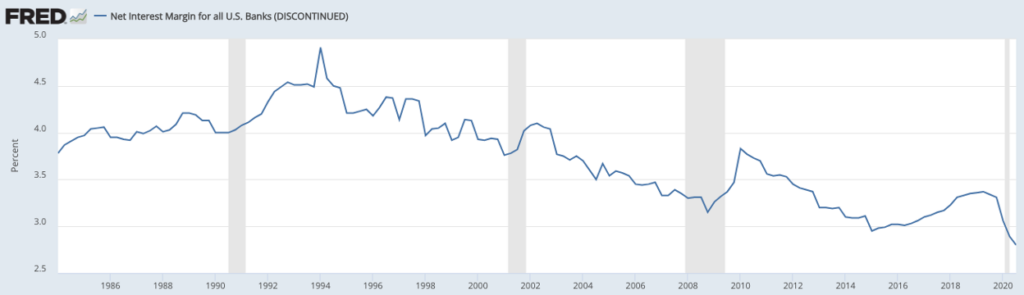

Over recent decades, however, average NIM in the U.S. has steadily compressed. According to FDIC data, average NIM dropped from a high of 4.91% in 1994 to an all-time low of 2.56% in 2021, before rebounding slightly to 3.2% in 2024.

Now, as you might imagine, net interest margin is very sensitive to shifting macroeconomic conditions and monetary policy decisions. In rising interest rate environments (like what we saw in 2022 and 2023), NIM typically expands as banks raise loan rates faster than deposit rates, which lag due to customer inertia and banks’ reluctance to compete aggressively for deposits. Conversely, in low-rate environments, such as post-2008 or 2020, NIM usually compresses because loan yields fall faster than deposit rates, which are constrained by the zero lower bound. Recessions also pressure NIM, as loan demand weakens and banks lower rates to attract borrowers while maintaining competitive deposit rates.

This explains the variance quarter-to-quarter and year-to-year in banks’ NIM. However, it does not explain why NIM has steadily compressed since Q1 of 1994:

The reason for that steady downward trend is competition. Specifically, it was the confluence of three different trends in bank competition, which all started in 1994, as I noted in an essay last year:

- Interstate Banking — In 1994, President Clinton signed the Riegle–Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act into law. It allowed banks to branch across state lines and allowed bank holding companies to acquire banks in any state, regardless of state law.

- The Internet — In 1994, Tim Berners-Lee left CERN and founded the International World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the Mosaic web browser — one of the earliest web browsers, capable of multimedia browsing — became available across PC and Macintosh computers, and the number of web servers increased from 500 to more than 10,000, which helped get more than 10 million people online for the first time.

- Risk-based Pricing — In 1994, Signet Financial Corp spun off its wildly profitable credit card business into a monoline company, Capital One. Capital One pioneered the use of data analytics for risk-based pricing (i.e., individually evaluating and pricing the risk of each credit card customer rather than offering a single rate for all customers).

Interstate banking leveled the competitive playing field, allowing all U.S. banks to compete with each other. The internet supercharged this competition and made it significantly faster and easier for bank customers to open new accounts and move their money around. And risk-based pricing and data-driven customer segmentation enabled banks to compete on price at a more granular level (to the benefit of bank customers).

Over the last 30 years, shopping for the best price in banking has slowly transitioned from a luxury only available to the rich to a reasonable option available to the mass market.

And the challenge for banks will become much more difficult over the next 30 years because customers’ ability to navigate that flattened competitive landscape will continue to be supercharged by technology, specifically the combination of open banking and generative AI. From the same Fintech Takes essay:

Picture little ‘rate optimization robots’ roaming around the market, working on our behalf, constantly trying to refinance our loans and increase our deposits APY.

When rates move, bank customers will move … instantly. Price discovery will become perfect, and product utilization will become fully optimized.

I can’t stress this point strongly enough — this will happen.

This future will come to pass. We will have AI-powered agents continually optimizing the prices we pay for loans and get paid for our deposits. It is inevitable. And, as a result, banks’ NIM will be squeezed down to a level that we have never come close to seeing before.

And the question is — What can banks do about it?

Non-Interest Income

There is an obvious answer — non-interest income!

For decades, banks have supplemented NIM with non-interest income, primarily generated through fees assessed to customers and other industry stakeholders.

According to the FDIC, non-interest income as a percentage of total bank revenue peaked in 2005 at roughly 43%. Since then, it has steadily declined, reaching 29% in Q4 of last year. And the reasons for the decline of non-interest income tell us a lot about the strategies that work (and don’t work) when you’re trying to create a durable replacement for NIM on your balance sheet.

Let’s start by looking at the strategies that don’t work well. There are three basic categories:

- Fees you don’t see.

- Fees you incur accidentally.

- Fees you are misled or pressured into paying.

Fees You Don’t See

The best example of this is interchange.

Interchange fees seem like they should be a dream come true for banks that are starved for non-interest income. A consistent, low-cost source of revenue that is generated by the customer (who thinks they’re getting the payment card for free) and paid by merchants (who are pissed about it, but are generally not in a position to not accept payment cards).

However, the problem with fees that the customer doesn’t see is that, over time, the customer devalues the product or service that those fees are quietly paying for. It leaves these non-interest income streams vulnerable to competitive and regulatory disruptions.

This is, of course, exactly what happened to debit card interchange in 2011. The Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act capped debit interchange for issuers over $10 billion in assets. The amendment wiped billions in non-interest income off of big banks’ balance sheets and failed to save consumers any money (merchants just pocketed the difference). And because the big banks had Jedi Mind Tricked their customers into believing that checking and debit cards should be free, they were unable to make up the revenue through new explicit deposit account fees, like Bank of America’s ill-fated $5 monthly debit card fee.

Fees You Incur Accidentally

Overdraft protection is the example here, obviously.

According to the CFPB, U.S. consumers paid about $15.5 billion in overdraft and non-sufficient funds (NSF) fees in 2019. That revenue was highly concentrated within a small segment of consumers whose cash flow management habits triggered frequent, unintentional overdrafts. Data from the CFPB tells us that consumers who incur more than 10 overdraft fees in a year — roughly 9 % of all account‑holders — pay nearly 75 % of the total overdraft/NSF fees collected by banks and credit unions.

Once again, this business model appears, on the surface, quite attractive. The misuse of the service by a small number of customers generates extremely high-margin revenue for the bank and allows it to continue offering checking accounts and debit cards for free (even after Senator Durbin eviscerated debit interchange).

The trouble is that people don’t like being punished for mistakes. It makes them resent the company that is profiting from those mistakes. Here’s an illustrative consumer complaint collected by the CFPB:

Since [July] 2021, [Company] has charged me nearly $400.00 in overdraft fees and despite asking to reverse some, I’ve been told they cannot offer any “courtesy” refunds at this time. … [This] is my primary banking relationship, where I have my paycheck deposited and pay my bills. However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain as the fees are very high, often more than the cost of the paid item. And they are very frequent, being assessed multiple times per week and even per day. It makes it hard to get by when deposits go straight to covering outrageous fees. I understand the Bank needs to make a profit, but this is ridiculous.

And beyond the resentment from customers, profiting off of product misuse is a great way to end up in the crosshairs of regulators, legislators, and consumer advocacy groups.

This, ultimately, is what ended up sinking overdraft as a significant revenue driver for banks. Between 2021 and 2024, the CFPB waged an intense rulemaking, enforcement, and PR war against “junk fees”, with overdraft and NSF fees being right in the middle of the bullseye. And they won! Capital One’s decision to move to fee-free overdraft protection in 2021 was the first big domino to fall, and most large banks quickly followed suit. The result, according to the CFPB, was a 51 % drop in overdraft/NSF revenue between 2019 and 2023, which saved the average household that overdrafts $185 per year.

Fees You Are Misled or Pressured Into Paying

As Charlie Munger famously said, “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

There have been numerous, high-profile examples of sales incentives leading to bad customer outcomes in financial services. Regarding non-interest income, an instructive example is how some financial institutions have sold payment protection insurance in the past.

Lenders and insurers have worked together for decades to offer borrowers optional insurance, which ensures that loan payments continue to be made in the event that the borrower experiences a covered event like involuntary job loss or disability.

These products are attractive add-ons for lenders, as they generally have good margins and, when designed and distributed well, lead to positive downstream effects for lenders and consumers (fewer defaults, avoid damage to credit scores, lower servicing and collections costs, lower allowances for credit losses, etc.)

However, when these products aren’t designed and distributed well, significant consumer harm can happen. The famous example of this is the Payment Protection Insurance (PPI) scandal that unfolded in the UK between the mid-1990s and the late 2010s.

During that time, virtually every personal loan, mortgage, credit card, and auto loan in the UK came with a bolt‑on PPI policy. Branch staff and brokers got bonuses based on the “attachment rate,” so the easiest way to hit the target was to pre‑tick the PPI box or gloss over exclusions that might make the customer ineligible for protection. Commissions routinely exceeded 60% of the premium, and in the landmark Plevin v Paragon case, the undisclosed commission hit 72 % of the customer’s payment.

Once the UK banking regulators and the courts finally got their hands around the problem and started forcing banks to refund customers, the financial hit was substantial. By the August 2019 claims deadline, UK banks had set aside more than £50 billion for refunds and administrative costs — roughly equivalent to a full year of industry profit.

The great irony, across all of these examples — interchange, overdraft protection, payment protection insurance — is that the core benefit (peace of mind) is something that most consumers want. They want payment cards with ubiquitous acceptance and robust fraud controls and dispute management processes. They want the flexibility to access additional liquidity at the point of sale. And they want to protect the good standing of their loan accounts (and their credit scores) from unanticipated disasters.

Indeed, many of the products that banks have built over the last 30 years to drive non-interest income are ones that consumers truly do value and are willing to pay for.

The problem isn’t what non-interest income products are being built. The problem is how those products are being packaged, priced, and distributed.

Banks have a lot of the right product ideas. They just have the wrong strategic and operational playbook.

Perhaps it’s time to look outside of banking for a new playbook.

Costco

When Craig Jelinek took over as CEO of Costco in 2012, he told the outgoing CEO (and co-founder) Jim Sinegal that he was going to need to raise the price of the retailer’s famous $1.50 hot dog & soda combo meal, Sinegal replied, “If you raise the effing hot dog, I will kill you.”

Sinegal expressed a similar sentiment when asked by the Seattle Times what it would mean if the price of the hot dog combo ever did go up, saying, “That I’m dead.”

Sinegal’s fanaticism about the price of the Costco hot dog isn’t a random quirk. It is the outgrowth of a deep-rooted philosophy that has propelled Costco to enormous success.

Costco is the third-largest retailer in the world. Roughly one-third of U.S. consumers regularly shop at a Costco warehouse. The company made roughly $250 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2024. But the most important fact to know about Costco is that more than 70% of the $7.3 billion in profit that it made last year came from membership fees.

To put that into the context of this essay, approximately three-quarters of Costco’s annual profit comes from non-interest income.

So, how does Costco’s playbook work?

Well, as you likely know, you must be a Costco member to shop in the store. The basic membership costs $65 per year. The premium membership (which comes with additional benefits like 2% rewards) costs $130 per year.

And once you can shop in the store, you get access to the incredible breadth, quantity, quality, and low prices that Costco is famous for. Everything from rotisserie chickens to pressure washers.

Like any good warehouse club retailer, Costco leverages its scale to negotiate incredible deals with its suppliers, which includes getting iconic brands like Levi Strauss & Co. to produce superior versions of their products for Costco’s private label brand, Kirkland:

Costco’s private-label brand does so much volume ($50B+ in sales) that vendors will bend-over backwards to get into the warehouse. The vendors will even produce a Kirkland-branded product that is “at least 1% better than the equivalent branded products (on some metric of Costco’s choosing)”. Even if this Kirkland product cannibalizes sales from a vendor’s own business, the Costco volume is worth it. This applies to all types of products from instant coffee to cashews to golf balls.

And this is where Sinegal’s fanaticism comes into play — Costco will not charge more than a 14-15% margin on any product it sells. In fact, most of the retailer’s products have a mark-up of less than 10%.

This discipline is absolutely essential for Costco’s flywheel (plentiful quality at great prices → more members → more leverage with suppliers), but it’s extremely difficult to maintain, as this anecdote from Sinegal illustrates:

While speaking with MIT students in the early 2010s, Sinegal explained how Costco once negotiated a big discount on Calvin Klein jeans and why the retailer didn’t keep the extra margin.

“We pass the savings on to the customer, every time,” Sinegal said. “Do you know how tempting it is to make another $7 on a pair? But once you do it, it’s like taking heroin. You can’t stop.”

This is one of the reasons why Costco sends every premium member an annual “membership dividend” e‑mail a couple of months before their membership renewal date, which includes a certificate for the amount of rewards earned on qualified purchases and an exact accounting of how those rewards were earned. Knowing that every member will see an itemized rebate helps Costco’s leadership team keep itself and its suppliers honest: if margins creep up, rebate checks balloon, and profit comes under pressure.

It’s also why Costco’s membership renewal rate exceeds 90% worldwide. Members understand exactly what value they are getting and are happy to continue paying for it.

Build Better Bundles

It’s not an accident that Costco refers to its customers as “members.” Indeed, you cannot be a Costco customer without first becoming a Costco member.

A number of fintech companies, including Chime and SoFi, do this as well.

And, of course, credit unions are famously strict about using the term “member” instead of “customer” (so much so that if you make this mistake when talking to a credit union employee, you can kiss whatever credibility you had with them goodbye).

Why? Why is using the term “member” so important to these companies?

I believe one reason is that it’s a way of holding themselves accountable. When you frame your products and services as a “membership”, and, crucially, when you charge a transparent, fixed fee for that membership, you are committing yourself to delivering enough value to members to make the fee worth it.

And the best way to ensure that the fee is worth paying is to use your scale to concentrate pricing power and spread out risk to create a bundle of shared benefits that strengthen the value of your core products.

Put simply, the key to building durable non-interest income streams is better product bundles.

The composition of these bundles can and should differ between banks, based on their product offerings and target customer segments, but, in general, they should revolve around a few core pillars.

Software

Financial products exist to enable workflows. Oftentimes, a single product type can be the keystone for numerous different personal and professional workflows.

For example, a checking account can enable fee collection, repair payments, and property tax escrow for a homeowners association, but a checking account can also be used to enable chore assignments and tracking, allowance payments, and financial literacy lessons for kids.

Purpose-built software can be wrapped around core bank products to help manage these different workflows more effectively. PayHOA does this for independent homeowners associations. Greenlight does this for kids and families. And each of these software + bank product bundles can be sold the same way that any other SaaS software product is sold — as a recurring subscription.

Bundled software that adds workflow-specific utility to undifferentiated bank products can be a strong source of non-interest income growth.

Pricing

One-third of U.S. consumers funnel their grocery, electronics, and toilet‑paper spend through a single wholesaler. That volume lets Costco squeeze unit economics so hard that suppliers will manufacture “Kirkland‑plus” versions of their own brands just to stay on the shelf. The membership fee buys you entrée into that purchasing co‑op, and Costco sends an end‑of‑year dividend to prove the savings are real.

Banks can wield their balance‑sheet scale the same way.

A common approach today is on-us relationship pricing. A customer gets a small deposit rate bump if they give the bank their direct deposit, or the bank waives a fee if the customer keeps a balance in the account above a certain threshold.

Less common, but intriguing, is the idea of a bank leveraging its collective purchasing power to negotiate off-us deals for members. For example, imagine a bank coordinating a solar panel installation project for the members of a small community. The bank gathers commitments from individual home and business owners, negotiates bulk equipment and installation pricing, and finances the deal with a competitively priced loan.

It’s surprising to me that a Costco-style “negotiate the best possible prices for paying members” service hasn’t already gained traction at a bank or fintech company (why, for example, doesn’t Credit Karma do this?) However, I think it’s inevitable as NIM continues to compress.

Peace of Mind

If Costco’s flywheel relies on concentrating buy‑side power, the flip side for banks is spreading risk across the member base. Payment protection products (like TruStage’sTM Debt Protection, Credit Insurance, and Payment Guard Insurance) are a textbook example of risk‑sharing as a value-added member service.

As I mentioned above, consumers want this safety net. In a survey of 1,011 U.S. consumers earlier this year, TruStage found that 85% were concerned with their ability to make loan payments due to potential life events. Consequently, 82% of consumers would be interested in payment protection if they were made aware of it (up from 60% in 2023)1.

The key is to offer these risk-sharing products transparently, at a fair price, either embedded within the digital account opening process or sold by well-trained and thoughtfully incentivized loan officers.

(Editor’s Note — TruStage has nearly a century [yes, a century] of experience helping lenders design and implement distribution strategies for payment protection products, through person-to-person channels and, more recently, embedded in digital channels and experiences, that align the interests of lenders and their customers and ensure such products are in full compliance with regulations. If you have questions about what the best practices are in this area, TruStage is the company to talk to.)

If you can do this, you can create the bank equivalent of Costco’s extended warranty desk — a voluntary, high‑attachment add‑on that turns catastrophes into inconveniences.

This Is The Way

NIM is in structural decline. The financial services industry has become extremely competitive and is poised to become even more so in the decades to come. Winning in this environment will require banks to make significant investments in growing non-interest income.

However, non-interest income is only as good as the reputation of the product that generates it. If that reputation is poor; if the product is opaque or punitive or coercive, it won’t last long.

The only durable strategy is to build product bundles that customers will explicitly and happily pay for. If we want banks to survive (and trust me, we do), this is the way.

ABOUT TRUSTAGE

TruStage is a financially strong insurance, investment and technology provider, built on the philosophy of people helping people. We believe a brighter financial future should be accessible to everyone, and our products and solutions help people confidently make financial decisions that work for them at every stage of life. With a culture rooted and focused on creating a more equitable society and financial system, we are deeply committed to giving back to our communities to improve the lives of those we serve. For more information, visit trustage.com

TruStageTM Payment Guard Insurance is underwritten by CUMIS Specialty Insurance Company, Inc. CUMIS Specialty Insurance Company, our excess and surplus lines carrier, underwrites coverages that are not available in the admitted market. Product and features may vary and not be available in all states. Certain eligibility requirements, conditions, and exclusions may apply. Please refer to the Group Policy for a full explanation of the terms. The insurance offered is not a deposit, and is not federally insured, sold or guaranteed by any financial institution. Corporate Headquarters 5910 Mineral Point Road, Madison, WI 53705.

PGI-8003371.1-0525-0627

- Source: TruStage 2025 Consumer Lending Preferences Research, 2025 ↩︎