I’ll be honest with you. Of all the terms I run across in my job, one of the ones that I understand the least is customer lifetime value, or LTV for short.

And yet … the term is essential to understanding the recent past and, more importantly, the future of fintech and banking. Every company working in the financial services industry cares about growth, and LTV is the pathway to growth.

So, in today’s essay, I will work to define exactly what LTV is, explore the evolving competitive dynamics that have made it such an obsession in our industry, and lay out a new roadmap for building it.

What is Customer Lifetime Value?

Put very simply, customer lifetime value is all the money a customer will likely make you, minus all the money they’ll likely cost you, over the time they stay as your customer.

In financial services, providers make money from customers through net interest margin (the difference between the interest you pay to borrow money and the interest you collect when loaning money) and non-interest income (typically fees, such as subscriptions, interchange, origination fees, account/advisory fees, etc.)

On the cost side, you have to factor in both upfront acquisition costs (anything you pay to acquire the customer, such as paid media or promotions) as well as any ongoing expenses, specific to customers (i.e., not corporate overhead), such as credit and fraud losses (minus any money recovered), variable servicing costs (e.g., disputes, servicing, or anything else that scales with usage), rewards and network costs, partner revenue splits (which are especially relevant to fintech companies working with bank partners), and funding and capital costs.

These revenues and costs are modeled against a retention curve, which measures the percentage of active customers that a provider expects to hold onto, month-to-month. The better your retention curve, the better your expected LTV.

LTV can be (and usually is) calculated on an individual product basis (i.e., how profitable is our consumer credit card portfolio?) However, customer LTV — profit from all the products a customer is likely to use over time (checking → card → loan → investments), weighted by how likely adoption of each product is and how long customers stick around — is widely considered to be the more strategically important lens through which to view your business.

As with any all-in metric, there are a lot of contributing factors to customer LTV. A lot of different levers that banks and fintech companies can pull on, including:

- Acquisition efficiency: Referrals and organic growth, as well as smarter targeting for paid spend, can lower the customer acquisition cost (CAC).

- Margin: Lower funding costs, less customer price sensitivity, and favorable network and partnership deals can improve profit margin.

- Risk: Lower credit and fraud losses through better underwriting and risk controls can reduce expenses.

- Cost to serve: automation, self-service, and other investments in efficient servicing can further reduce expenses, especially as scale increases.

- Capital efficiency: Optimized use of capital (securitization/loan sales, better underwriting/collateralization, etc.) improves profitability and fuels growth.

However, all of these sit below the two primary levers for customer LTV: depth and duration.

Depth is how many of a customer’s real-world money jobs you become the default for — getting paid, paying bills, daily spending, saving, borrowing, investing, and protecting assets. Not “products owned,” but “problems solved.” Duration is how long you hold that primacy before someone else pries it away. Get both right and the other levers — margin, risk, servicing cost, capital — have more time and surface area to compound.

Depth without duration is a sugar high. There are lots of ways to increase the number of products per customer, but most of them are not sustainably profitable for the financial services provider or durably valuable for the customer.

Duration without depth is mindless inertia. Many financial services providers fool themselves into thinking that a long customer relationship means that the customer is waking up every day and explicitly choosing to work with them, but that’s an unsafe assumption if the customer isn’t growing their use of the providers’ products over that time as well.

The pursuit of customer LTV, in other words, is the dual pursuit of earning the next job and sticking around long enough for it to matter.

How We Got Here

A little history is important at this point in our story.

For most of the 20th century, U.S. banks were local monopolies (or, at most, oligopolies). Like newspapers, banks operated in specific geographical communities (cities, counties, states) and commanded significant market power through their branch-based distribution networks. For the most part, consumers banked where their parents banked, or with whatever bank had the strongest acquisition muscle in the community that the consumer moved to. As long as the consumer didn’t physically move to another community, customer retention was an assumption. It was a hassle to switch banks, and there was usually no compelling reason to walk your business across the street because the bank on the other side offered the exact same products.

The apogee of this era came in the early 2000s when, after a series of deregulatory actions, including the Riegle–Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994, large banks began to pursue universal banking. This distribution model combined maximum product bundling (literally offering the entire universe of financial products — deposits, loans, payments, wealth management, insurance — under one roof) with unparalleled operational efficiency enabled by national scale. The idea was to pursue the deepest possible relationships (through cross-sell) with the largest possible number of customers, while continuing to assume a robust retention curve enabled by multi-product relationships and a lack of meaningful customer choice (i.e., once you selected your universal bank, there would be no real reason to switch).

The universal banking era would turn out to be short-lived, and not just because of the overzealousness of certain practitioners like Wells Fargo.

The emergence of the internet and smartphones erased geographic barriers and rendered banks’ carefully constructed distribution moats irrelevant. On this suddenly level playing field, product and pricing mattered far more than they ever had before. And fintech companies — with their ample VC funding, low-cost operating models, and significant product and UX design chops — suddenly had a significant competitive edge.

This, of course, led to the era that we are all familiar with: the era of unbundling.

Unbundling is a straightforward playbook: pick one painful job that banks treated as an afterthought and do it 10x better.

Replace customer-level underwriting and revolving debt with transaction-level underwriting and a simple no-fee installment loan (pay-in-4 BNPL). Replace punitively-priced overdraft protection with small-dollar loans advanced against already-earned wages (earned-wage access & two-day early pay). You get the idea.

Unbundling, as a trend in financial services, peaked in roughly 2021, when multiple monoline fintech companies raised funding at $1+ billion valuations, on the strength of their growth, product velocity, and, most crucially, a promise: to rebundle.

Rebundling (Universal Banking in Different Clothes)

Once the wedge was won, the next slide in every fintech deck practically wrote itself: “We’ll become their primary money app.” The logic was familiar — if you already have the customer’s attention (and ideally their paycheck), then adding adjacent jobs (credit, investments, insurance) should lift product penetration, amortize fixed costs, and — abracadabra — elevate customer LTV.

One example that I remember from this time was SoFi, which went public (via a SPAC) in 2021.

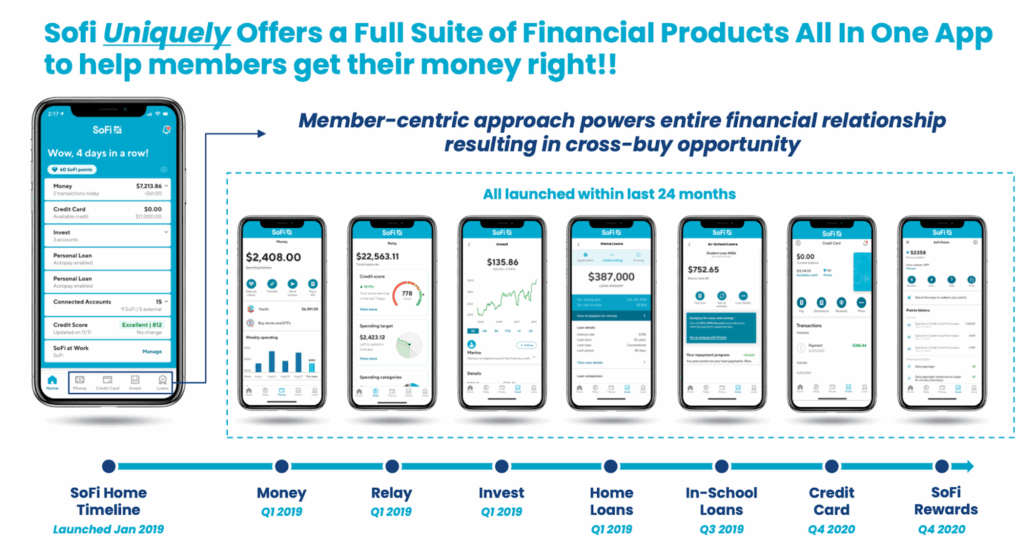

Here is a slide from SoFi’s investor presentation:

SoFi used terms like “cross-buy,” “vertical integration,” and “financial services productivity loop,” but really, it was just universal banking, dressed up in slightly different clothing.

And the challenge for SoFi, in pursuing this same strategy that Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Citi, JPMorgan Chase, and numerous other banks (large and small) pursued decades earlier, was that it had no more inherent right to win consumers’ business in adjacent financial product categories than those banks did.

And unlike the 1990s and 2000s, the 2020s have been a decade defined by consumer choice. In this competitive environment, if you want to jump from 1 product per customer to 2 products per customer, that second product needs to either be best-in-class or profoundly complementary to the first product (1 + 1 = 3).

SoFi has, so far, failed to clear these bars, which is why its products/customer ratio has stubbornly hovered between 1.4 and 1.5 since going public.

This isn’t meant to be a criticism of SoFi, specifically, but rather of a vision of rebundling that carries universal banking-era assumptions about cross-sell and customer retention into today’s hypercompetitive era, in which banks and fintech companies struggle to even maintain competitive differentiation around their flagship products, let alone a portfolio of products.

Successfully selling one financial product to a consumer no longer guarantees you either the right to keep that customer or to sell them a second product.

So, if building customer lifetime value is still our goal (and it should be), perhaps we need to develop a new mental model for building, bundling, and selling financial products.

Life Stage Product Bundles

I recently had the privilege of speaking at MX’s Money Experience Summit, where I moderated a panel on generational differences. If you’ve worked in financial services for any length of time, you’ll know that we are obsessed with generational differences. However, what made this panel unique was that the participants were all members of different generations, none of whom (apart from me) work in financial services.

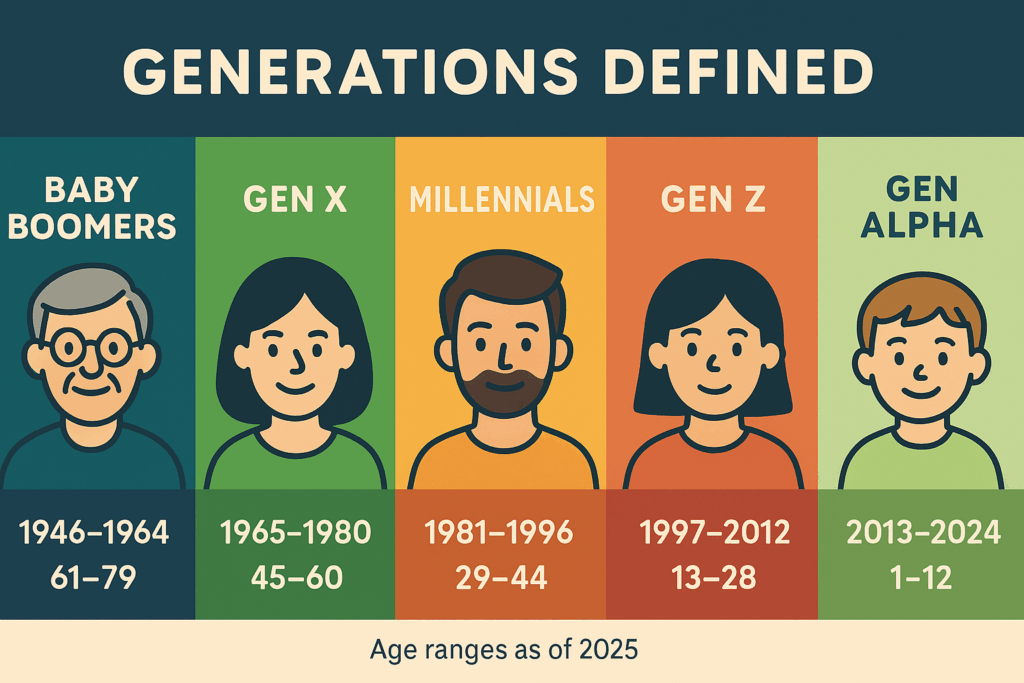

Starting on the left and going in order, we had a Baby Boomer (technically Generation Jones), two Gen Xers (of different ages), a Millennial (me!), a Gen Zer, and an older member of Gen Alpha (not pictured below … but envyingly poised and articulate for a 16-year-old!)

In the course of the discussion, two things became clear to me.

First, much of what we consider to be “generational preferences” are not actually unique to a specific generation, but rather belong to specific life stages.

While Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, Gen Z, and Gen Alpha do have characteristics that are particular to them (we’ll discuss some of them in a minute), many of the things we associate with consumers from those generations are, more accurately, characteristics of all consumers at that age.

Credit cards are the classic example. Every 15-20 years, a slew of news stories report that the current generation of twentysomethings is ditching credit cards for debit cards or cash or mobile wallets. And then, 5-10 years later, a new raft of news stories comes out, claiming that actually, this generation really does like and use credit cards (sometimes more than the prior generation at that age). The truth, of course, is that 18-25 year olds don’t have much use for credit cards, but 26-40 year olds get a great deal of value out of them.

This is important for financial services providers because it suggests that designing products for specific life stages (childhood, adolescence, early household formation, middle age, pre-retirement, retirement, etc.) can be both fruitful and sustainable.

And second, based on the financial challenges shared with me by members of the panel, there is a large number of finance and finance-adjacent problems, specific to different life stages, that have not yet been adequately solved by banks and fintech companies.

This is an opportunity.

People don’t experience money as a catalog of SKUs. They experience it as a sequence of recurring life moments that line up — roughly — with age and circumstance. Designing for life stages is not about having every possible product; it’s about sequencing the smallest helpful intervention at the moment it will actually be used — and earning the right to help again in the next moment.

That’s how banks and fintech companies compound depth (doing more jobs-to-be-done) and duration (longer, stickier relationships). It’s also how they sidestep the “best-in-class or bust” trap: you don’t have to outshine every competitor on every dimension if you show up first and usefully at the right moment.

What would that look like in practice?

I’m so glad you asked!

Life Stage-based Product Design

I’m going to walk through four specific examples:

- From Spending to Saving

- Early Household Formation

- The Sandwich Years

- Pre-retirement & Retirement

From Spending to Saving

When I asked my Gen Z panelist about her most pressing financial challenges, she was wonderfully direct and candid: she needs help not spending money.

While young adults have always struggled with impulse control (and always will), this is a problem area where the evolution of technology has had a specific and negative impact on Gen Z. The combination of social media — built on top of a free, ad-supported business model — and frictionless transactional payment and lending capabilities (BNPL, in particular) have made it both tempting and incredibly easy for today’s young adults to spend all of their money. The Gen Zer on my panel described the constant challenge of seeing her friends making purchases (particularly on experiences) and giving in to the temptation to do the same, rather than to save or pay down debt.

What young adults need is a product focused on control and perspective.

This product would be savings-oriented, by default, with intelligent automation that quietly shaves a predictable amount off each paycheck into goal buckets, adds reversible “speed bumps” on discretionary spikes (this is 3× your normal food delivery this week — still want to proceed?), and offers just-in-time liquidity with transparent costs and limits rather than punitive overdrafts. It would also work to counter the FOMO effects of social media by giving users a realistic view of their financial progress, relative to their peers, and specific and tangible insight into the benefits of delayed gratification.

Early Household Formation

I’ve been a fan of the “couples banking” category in fintech for a long time.

I remember the types of money-adjacent fights my wife and I would get into when we first moved in together, and it frustrates me to think how many of them could have been avoided or made more productive through the use of well-designed, finance-infused software.

Early household formation looks like a product problem (give them a joint account), but it’s actually a choreography problem. Couples want coordination without surrendering autonomy. The right model could link two primary accounts with clear rules — who pays which bills, how to split irregular expenses, when to move surplus into shared goals — while preserving separate spaces for personal spending.

The moment a household decides to buy a car or a home, the product could generate a set of tasks — document collection, soft pre-qual, debt-to-income coaching, rate holds, and a date-driven closing plan — to reduce their collective anxiety and create more confidence in their shared financial future.

The Sandwich Years

The younger Gen Xer on my panel was a perfect representative of someone caught in what I think of as the “sandwich years” of personal finance.

This is the time in a consumer’s life when they are likely at their professional peak — working a large number of hours and making the most money they will ever make in their career — while simultaneously being responsible for helping to manage the financial lives of their teenage and young adult children and of their aging parents.

The Gen Xer on my panel described the frustration of beginning to plan for retirement (which may be as few as 10 years away) while also having to account for the uncertainty of not knowing when all of her children will “leave the financial nest,” which is something that today’s young adults are doing at later and later ages.

Consumers in this stage of life are sometimes asset-rich, but they are almost always time-poor. A helpful financial product for this life stage would function like an air-traffic controller: a cash-flow calendar that aligns bills to paydays, flags mismatches before they become fees, and offers one-tap fixes; role-based permissions that let a spouse sweep up to a limit, give a sibling read-only visibility into Mom’s account, and require dual-approval for large transfers; and “smart sweeps” that top off sinking funds (insurance premiums, car repairs) before pocketing yield or pre-paying debt in a prioritized order.

Pre-retirement and Retirement

The sentiment shared by the older Gen Xer and the Baby Boomer on my panel (both of whom are retired) was that there is no shortage of educational information about preparing for and managing your finances during retirement, and opportunities for sitting down with human financial advisors are plentiful (and easier to seize since these consumers have more free time). However, there is a noticeable lack of software designed to help older consumers transition from “grow the pile” to “enjoy spending the pile while making sure it will last.”

This is a very difficult mindset shift. Consumers preparing for retirement, or who are in the “unemployed but not yet officially retired” stage, want tools that can translate assets, risk tolerance, and tax status into a believable monthly paycheck, then let them adjust the dials and see — in plain language — the tradeoffs they’re making. If spending rises by $200 a month, how does the probability of depletion change by age 90? If markets draw down by 15%, how does the plan adapt without panic selling?

Consolidation matters as much as allocation. Consumers want to be able to pull scattered accounts into a single system for withholding, beneficiary hygiene, and document storage. They want help making tax moves tangible and timely: nudge on Roth conversion windows, catch-up contributions, HSA funding, and charitable giving strategies tied to the calendar rather than abstract guidance.

Retirement itself is about a paycheck and a perimeter. The paycheck is a rules-based drawdown that lands on the same day each month, implements a simple bucket structure (cash, near-cash, long-term), and smooths market noise without requiring constant customer decisions. The perimeter is a set of layered protections: trusted contacts who are notified of unusual activity, watchlists for risky payees and gift-card patterns, and caregiver collaboration tools with granular permissions and an auditable log.

(Editor’s Note — As mentioned earlier, these financial safety and protection capabilities for older consumers are also a critical component of the ideal financial product for middle-aged consumers in the sandwich years.)

Life Stage Bundles Are Already Being Assembled

In case you think the vision I’m laying out here is entirely theoretical, I should mention that there are already banks and fintech companies that are bringing it to life.

A good example is Acorns.

The company was founded in 2012 (which is ancient, in fintech) with an initial wedge built to help those young adults we mentioned earlier, by automatically “rounding up” purchases and automating small, habitual contributions.

From there, Acorns started stitching together the rest of the young-adult arc.

In 2017, it acquired Vault and launched Acorns Later, pulling IRA automation into the same app flow as round-ups and paycheck skim. The leap from “I save without thinking” to “I contribute to retirement without thinking” became a one-tap progression rather than a new relationship.

In 2021, the Harvest acquisition added found-money mechanics — fee negotiation and automatic refunds — that reduce leakage. For a cohort whose biggest constraint is not investment selection but cash friction, this is precisely the kind of “everyday win” that keeps the habit alive. When customers repeatedly experience money appearing rather than evaporating, they keep showing up.

Then Acorns expanded the circle to the household. In 2023, it acquired GoHenry, bringing allowances, chores, first cards, and parental controls into the fold. That move reframed Acorns from a single-user investing app to a family money environment. Parents now have weekly reasons to open the app, while kids and teens learn to spend and save within the same brand their parents already trust.

In 2025, two small but telling acquisitions rounded out the family arc. EarlyBird added custodial investing and a social gifting layer — the moment when families begin saving for children and relatives in a structured way. Zeta brought couples-and-families tooling: shared budgets, bill-splitting rules, and “linked but separate” account choreography. Together, these moves address the two most predictable inflection points after “starting out”: coupling up and saving for someone other than yourself.

What matters is the sequence. Round-ups win the first habit. Vault converts habit to long-horizon discipline. Harvest reduces regret and makes the system feel generous. GoHenry pulls the next generation into the loop. EarlyBird formalizes intergenerational saving. Zeta solves the coordination problem at the center of household finance. None of this depends on being the single “best” product in every category. It depends on being present with the smallest helpful tool at the exact moment the next job appears.

That is the life stage thesis in action. Not a universal catalog, but a choreography that compounds depth and duration as customers move from “me” to “we” to “family.” It is also a playbook most institutions could copy — if they are willing to organize roadmaps around stages, not SKUs, and if they build the plumbing to see those stages in the data.

Data Is the Foundation

I can’t emphasize this enough: life stage banking is not a branding exercise.

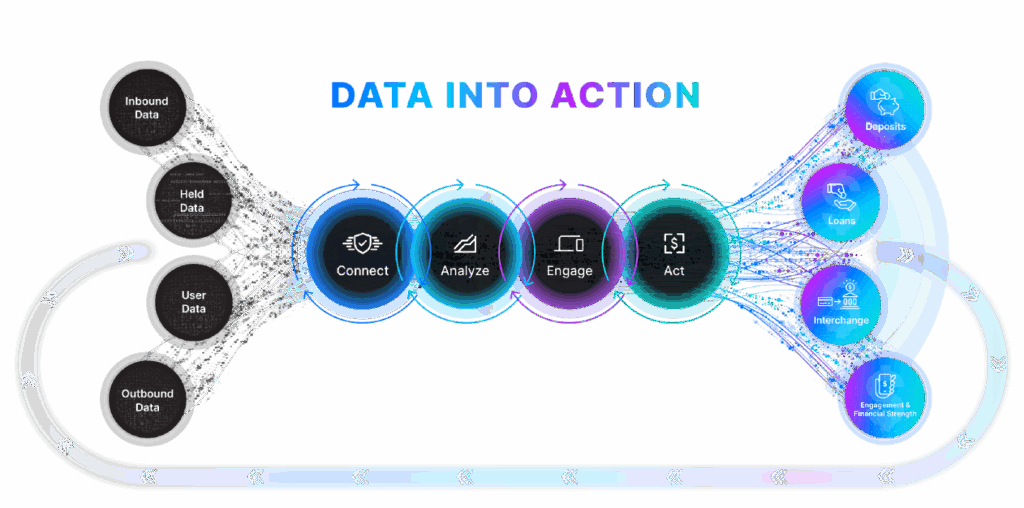

And no matter how good you are at product development and/or M&A, a life stage-based strategy for growing customer LTV will fail if you aren’t able to transform data into insights, take action in the right moment, and, ultimately, drive better financial outcomes for your customers.

As Nico Brown, Product Marketing Manager at MX, put it during Money Experience Summit:

This is how growth happens — moment by moment, person by person. When you can see what’s changing in someone’s life, understand what it means, and respond in the moment, that’s when you unlock growth that lasts.

You need to know the full picture of who your customer is — what you already know about them, combined with connected data from outside your walls. The good news? Consumers want this. They expect you to use their data to understand them better, personalize their experience, and give them clear, actionable insights into their money

According to MX research, more than half of consumers expect their financial provider to leverage the data they have about them to personalize their experience (58%) and use the data they have about them to provide them with actionable and clear insights about their finances (65%).

You need to know when something meaningful has happened. Tracking clicks and logins isn’t enough. You need to be able to recognize life events (first payroll, move, marriage, new dependent, retirement date) and money events (direct deposit posted, bill due, balance cliff, new payee, category spike). These moments are where trust is built or lost with consumers.

You need data that accurately reflects what’s happening on the ground in the lives of your customers — not just static snapshots. That means spotting patterns and signals — days to rent, income volatility, median discretionary spike, caregiver likelihood — and using them to drive live decisions.

You need humility about privacy and ethics. Life stage signals are powerful precisely because they are personal. And because these moments are so personal, they demand the highest standard of trust. Consent can’t just be a box to check. It should default to the minimum data needed to deliver the outcome. And it should be easy for consumers to see, change, and revoke permissions. The more sensitive the moment, the more important the explanation.

Finally, you have to do something. Seeing these moments means nothing if you don’t act on them. Data becomes action when it turns into a message, an offer, or a service that helps someone move forward with confidence. That’s how you grow deposits, engagement, and trust — one moment at a time.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by MX.

MX Technologies, Inc. enables financial providers and consumers to do more with financial data. MX provides end-to-end solutions for financial institutions and fintechs to connect to, analyze, engage, and act on consumer-permissioned financial data.