We’re going to start with a story.

One of my new colleagues at Workweek is in the process of buying a house.

Exciting!

She and her husband made an offer on a beautiful home in the Ladera Heights community in south Los Angeles. The offer was accepted (contingent on financing) and they worked with a mortgage broker to lock in a 30-year fixed rate loan with a large national bank at 4.5%, with 20% down.

They were less than a week away from closing on the house when something happened — their broker called and told them that their loan wasn’t going to be approved.

And the reason for this abrupt turnaround brings us to the heart of our story — cannabis.

Workweek covers a number of different verticals — fintech, climate tech, healthcare, marketing, media, startups, franchises, venture capital, and cannabis. And it’s that last one that caused the problem.

Now, to be clear, Workweek doesn’t sell cannabis or cannabis-related products. It doesn’t touch any part of the cannabis supply chain. It reports on the cannabis industry, in the exact same way that other media companies like the New York Times does:

But apparently that didn’t matter. The broker saw the word ‘cannabis’ on Workweek’s website and flagged it as a potential concern with the lender. When the lender asked for additional information in order to investigate, the broker panicked and pulled out rather than risk their commission.

This, of course, completely screwed over my friend. She and her husband had to scramble to find a different lender and lock in the same 4.5% rate (which is the absolute limit of what they can afford thanks to absurd real estate prices in southern California) at significantly worse terms (10-year ARM). And somehow this is, given the circumstances, the best possible outcome! She and her husband will still (fingers crossed!) be closing on their new home in the next couple of days.

Things could have gone significantly worse.

Which brings me to my questions:

- Why did the mortgage broker and lender do this?

- Who else might be getting negatively impacted by financial institutions’ unwillingness to work with certain consumers and businesses?

Let’s tackle the first question first.

Why is Cannabis Difficult to Bank?

It’s fairly simple — according to guidance from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), financial institutions are legally required to monitor for and report any financial activities that they suspect involve funds derived from illegal activity, which includes manufacturing, distributing, or dispensing marijuana:

Because federal law prohibits the distribution and sale of marijuana, financial transactions involving a marijuana-related business would generally involve funds derived from illegal activity. Therefore, a financial institution is required to file a SAR [suspicious activity report] on activity involving a marijuana-related business

Now, of course, the challenge is that while the distribution and sale of marijuana is illegal at a federal level under the Controlled Substances Act, cannabis products are currently legal for approved medical uses in 37 U.S. states and for recreational use in 18 states. Another 13 states have decriminalized the use of Cannabis.

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Cannabis businesses legally operating in these states need, you know, banks accounts and the ability to safely and securely transact with their customers and employees.

So the Treasury Department and the Justice Department put their heads together and clarified that while financial institutions are still legally required to report all financial activity involving cannabis (because technically all of it involves funds derived from activities that are illegal according to federal law), what they really want financial institutions to focus on are the cannabis-related financial activities that may be indicators of more serious criminal activities like financing drug cartels or selling marijuana to minors.

This has, believe it or not, led to the creation of a tiered reporting system for suspicious activity involving cannabis businesses.

If a bank starts working with a licensed cannabis business operating legally in a state that has legalized cannabis and that business isn’t doing anything to make the bank think it is involved in more serious criminal activities, the bank is required to file a ‘Marijuana Limited’ SAR. This is basically the bank saying to FinCEN — this business appears to be perfectly normal and not doing anything remotely suspicious but, you know, MARIJUANA! so, heads up.

If a bank is working with a marijuana related business and it suspects that the business is actually breaking state laws or using its marijuana business to facilitate or disguise more serious criminal activities, then the bank is required to file a ‘Marijuana Priority’ SAR. This is the bank telling FinCEN — we actually think something bad is happening here and you should ignore all those marijuana limited SARs we filed and focus on these guys.

If this sounds unnecessarily complex and very difficult and time consuming to deal with, you are absolutely right! Which is why most banks don’t even bother to try to provide services to the cannabis industry.

And to bring our story all the way around, it’s likely why my friend’s mortgage broker stuffed its fingers in its ears and screamed “lalalalalalala” when the word ‘cannabis’ became attached to her mortgage loan application.

Who Else is Being Underserved by Banks?

And now let’s tackle the second question — who else might be getting negatively impacted by banks’ unwillingness to work with certain consumers and businesses?

We toss around the term ‘underbanked’ a lot. So much so that it’s honestly not that useful anymore. It has become this sort of bizarre umbrella term for everyone that banks don’t want to work with or aren’t allowed to work with or who don’t want to work with banks.

In the abstract, the term ‘underbanked’ does nothing for me. But that’s why my friend’s story is so important. It spotlights the individual harm that can occur as the result of industry-level regulations and institution-level compliance and risk management policies. It inspired me to ask this question on Twitter:

And whew boy, did folks respond!

Here’s a list of some of the examples that the wonderful fintech nerds on Twitter shared with me of banks ignoring or underserving specific customer or product segments:

Cannabis, Gambling, Short-term Lending, Subprime Lending, Fintech, Crypto, Remittances, Travel, Media, Kids & Teenagers, Older Consumers, Sex Work, Sexual Wellness, Adult Entertainment, Pharmacy, Jewelry, Precious Stones & Metals, Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms & Ammo, Medical & Chemical Exports, Seed & Agricultural Imports, Oil & Gas, Private Prisons, Charities, Gift Cards, Telemarketing, Multi-level Marketing, Immigrants & Refugees, Non-native English Speaking Communities, Small Businesses, Freelancers & Gig Workers, Family Farms, Seafood, Restaurants & Bars, Formerly-incarcerated Consumers, Pawn Shops.

There are a couple of interesting things about this list.

First, it’s much broader than the way we tend to conceptualize and define the unbanked and underbanked in official surveys and research studies, like this one from the FDIC on How America Banks:

An estimated 5.4 percent of U.S. households (approximately 7.1 million) were “unbanked” in 2019, meaning that no one in the household had a checking or savings account at a bank or credit union … The proportion of U.S. households that were unbanked (i.e., the unbanked rate) in 2019—5.4 percent—was the lowest since the survey began in 2009. Between 2017 and 2019, the unbanked rate fell by 1.1 percentage points, corresponding to an increase of approximately 1.5 million banked households.

That’s fascinating data, but it doesn’t come close to telling us the whole story. It doesn’t, for instance, include mortgage loans or the number of otherwise-fully-banked consumers who struggle to get mortgages because of banks’ aversion to working in or even remotely adjacent to the cannabis industry.

The second thing that is interesting to me about the list of underserved customer segments is just how diverse it is.

You have totally legitimate industries (seed & agricultural imports) and somewhat questionable industries (multi-level marketing). You have industries that are legal, but morally dubious (tobacco) and industries that sit in a legal gray area (gambling). You have entire sectors of the economy (small businesses) and entire sectors of the U.S. consumer population (immigrants & refugees).

It defies easy categorization, which helps explain why solving the underbanked problem is so hard — people and companies aren’t underserved by banks for one reason; they’re underserved for a whole bunch of intersecting and overlapping reasons.

Still, despite the challenge, I think it’s worth trying to at least narrow in on what some of those reasons are.

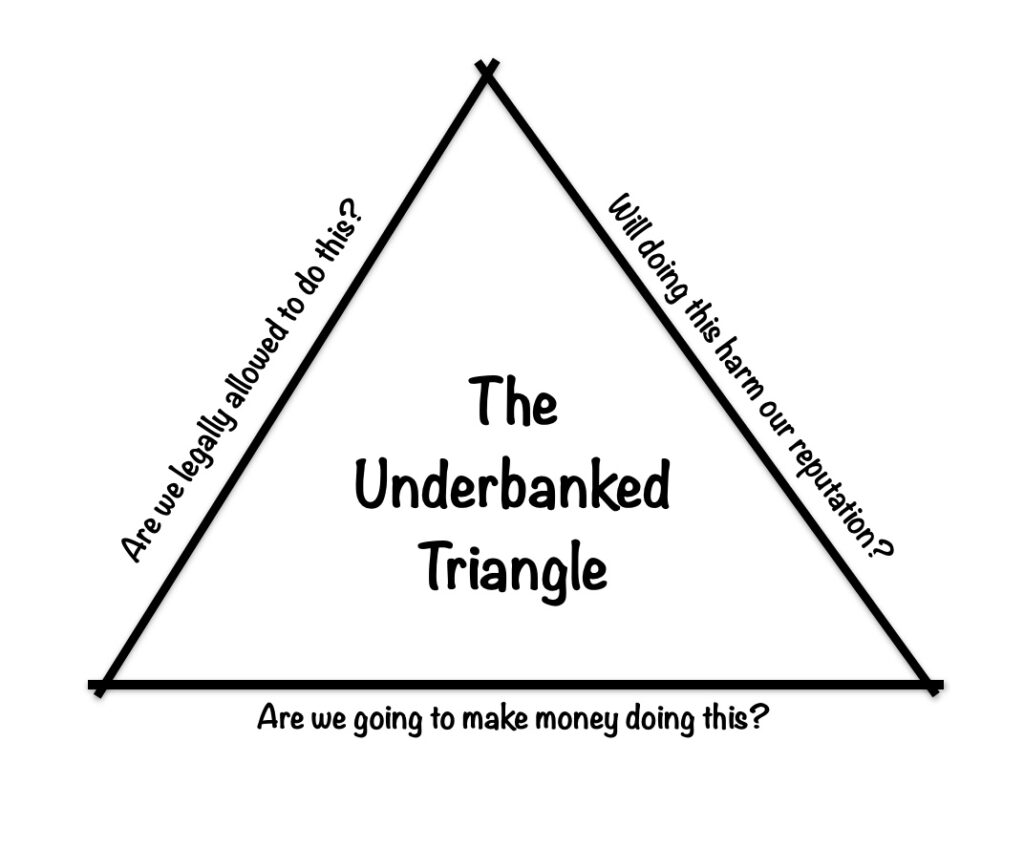

I think they fall into three main categories, which I will frame as questions that any bank needs to answer in order to work with a person or company:

1.) Are we legally allowed to do this? Banks aren’t allowed to facilitate financial transactions for criminals. From a societal perspective, this is generally a good thing (terrorists are a customer segment that everyone agrees should be underbanked), but it can get tricky when you get into areas where the laws are unclear or in the process of changing (the wonderful brand of federalism that we have in the U.S. complicates this further). Cannabis, gambling, and sex work are all examples of customer segments that fall into this legal gray area.

2.) Will doing this harm our reputation? This question comes in two different flavors.

The first flavor is your vanilla corporate brand reputation risk question. Banks are, by their nature, conservative. They don’t like to do things that may harm their reputation in the market or erode trust with their existing customers. Banks that have gotten themselves into trouble [cue Wells Fargo peaking their head out of the stage coach and giving a timid wave] tend to be especially sensitive to this risk.

The second is a mystery flavor — regulated reputational risk. In the 1990s, financial industry regulators like the OCC and the Federal Reserve and the NCUA adopted risk-focused frameworks for regulation. The idea was for regulators to prevent our increasingly complex and international financial system from suffering serious problems by proactively managing the risks that regulated financial institutions were taking. One category of risks that regulators started managing, within these frameworks, was reputational risk. Beyond ensuring that financial institutions don’t violate the law or take financial risks that undermine the safety and soundness of the U.S. financial system, regulators are now empowered to prevent banks and credit unions from doing things that might harm their reputations. Of course the problem with this is that defining reputational risk is really hard and subject to a lot of bias. However, that hasn’t stopped regulators from flexing this particular muscle, which has negatively impacted the availability of financial services for customer segments like oil & gas, short-term lending, and firearms & ammo.

3.) Are we going to make money doing this? This one is straight out of the Clayton Christensen back catalog. Banks have the luxury of a large, established, and very profitable customer base. They also have the constraints of short-term stockholder expectations for financial performance. This tends to disincentivize banks from investing resources in serving new customer segments that are less profitable or more expensive to serve than the customer segments they already work with. The “more expensive to serve” part is especially important, as banks have a high OpEx business model that relies heavily on human beings (rather than technology) to serve incremental customers. This is a big reason why banks have, historically, underserved customer segments like small businesses and kids & teenagers.

Obviously, these three questions aren’t independent of each other. There’s a lot of overlap between legal risk and reputational risk. Indeed, OCC examiners are explicitly instructed to consider a bank’s “potential or planned entrance into new businesses, product lines, or technologies (including new delivery channels), particularly those that may test legal boundaries” when evaluating their reputational risks. And if a bank decides to enter a business, product line, or technology that is considered legally or reputationally risky, that usually requires added compliance controls and processes and procedures (like all those marijuana SARs), which increases the overall costs for the bank and thus renders the new venture automatically less profitable.

These three questions are, in fact deeply interrelated. I’ve come to think of them as forming a Bermuda Triangle-like shape, from which risky customer segments may never escape:

It’s at least somewhat understandable how this ‘Underbanked Triangle’ was formed and why it persists. Not all of it is the fault of banks (read this paper for a much more detailed perspective on how regulators’ influence over reputational risk management can go too far). That said, as an industry, we can and we must do better.

Enter fintech.

Fintech Lobbying

You might have missed it, but ‘fintech’ was one of the segments mentioned in the list of underserved customer segments above.

It’s tough to imagine now, with banks’ increasingly enthusiastic embrace of BaaS, but back in 2009, banks were very suspicious of the notion that a consumer-facing fintech company could be built on top of their banking license, infrastructure, and balance sheet. Shamir Karkal, Brett King, and Jason Henrichs — some of the OG neobank founders — can give you hours worth of stories about how difficult it was to convince banks (and their regulators) to enable their crazy fintech ideas. Even the smallest things — like not requiring wet signatures in a digital account opening flow — required extraordinary work to get agreement on. The overall experience is summed up well by this anecdote, shared by Jason Henrichs on a recent episode of Breaking Banks:

The very first sit down I had with the OCC in my PerkStreet days, this is 2010, happened when we were bringing on our second issuing bank. We went to their regulator and sat down with them and said “here’s exactly what we intend to do, here’s why it doesn’t impact safety and soundness, here are all the guardrails” and their examiner leaned back in her chair, crossed her arms, and said “I don’t like it.” We asked why and she said “I can’t tell you. You’ll have to wait for your next exam.”

And yet, today we have a thriving fintech ecosystem, built on top of a growing BaaS infrastructure that includes banks and their (likely still somewhat skeptical) regulators! PerkStreet, Simple, and Moven banged their heads against the wall and then crawled and then walked so that today’s fintech companies could run.

And now that fintech, as a category, has broken through, fintech companies are persistently lobbying their bank partners (and those banks’ regulators) to let them serve other customer segments that the financial industry has traditionally underserved.

Stripe provides a good example of what this lobbying, at its best, looks like. The company put together an article describing why it is not able to support some businesses and how it works with its banking partners to expand the types of companies that it can support.

Here’s how Stripe explains why it restricts certain businesses based on reputational risks:

Financial institutions and payment networks care about the brand and reputational risk that associated businesses pose. There are a set of businesses that our financial partners do not want to be associated with even if there is market demand for them. Stripe doesn’t independently reject businesses based on brand risk—we have many unpopular businesses and causes on Stripe—but we’re at times obliged to enforce the restrictions of our partners. This category is highly subjective and therefore the one we like enforcing least.

We don’t think Stripe should be accepting or rejecting businesses based on a subjective determination of brand impact, and we feel the current brand restrictions (such as on sex toys) are often outdated and overly moralizing. We have only had limited success in supporting businesses in this category; there are many legitimate businesses we can’t support. Over time we hope to broaden the set of businesses in this category that we can support.

And here is an example of Stripe working with its banking partners to get approval to support a high-risk customer segment:

femMED was founded in 2007 to empower women to take a more natural approach to health and wellness. femMED has a nine-year history of helping women and has created 24 different licensed natural health products. Pseudo-pharmaceuticals are another historically-restricted category because of untested or unapproved products and exaggerated claims that often accompany the products. But we saw a business that had superb customer satisfaction, proven track record, and honest marketing claims. We highlighted the processing history and product approval by Canada’s natural health regulatory body that directly addresses key concerns of this industry and our financial partners agreed.

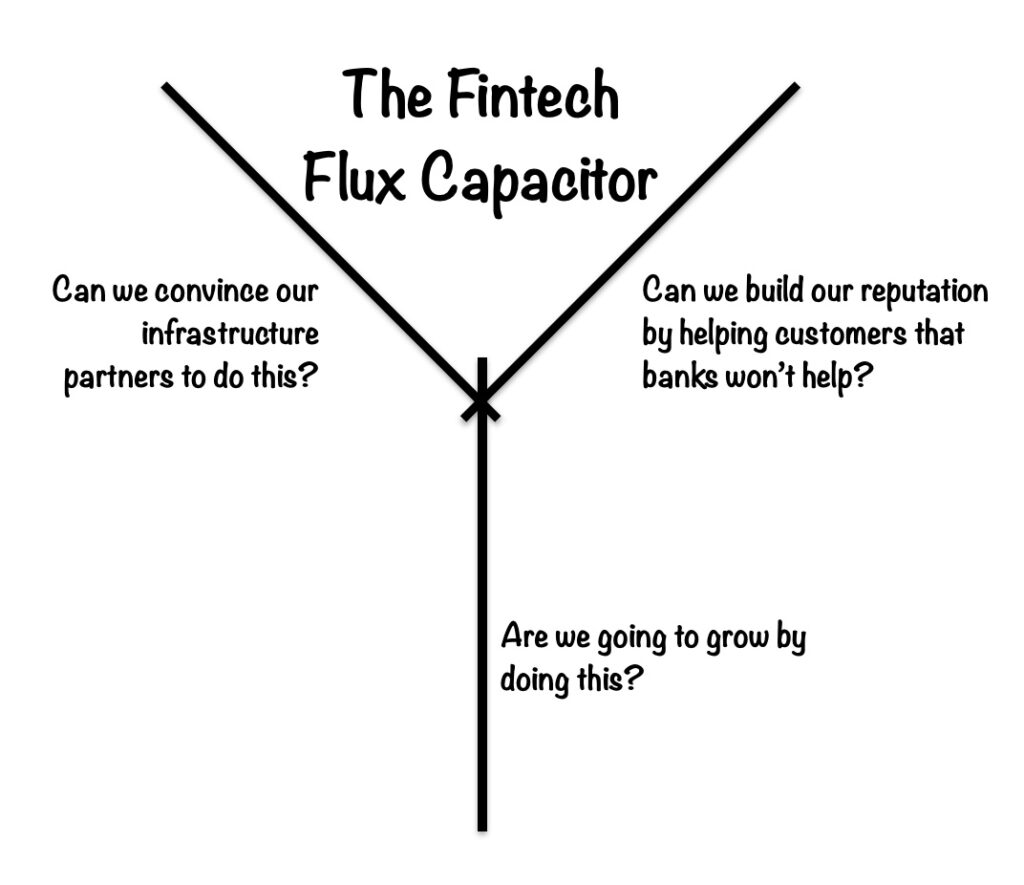

The reason that fintech companies are so persistent in their lobbying of banking partners to allow them to work with more customer segments is that fintech companies operate on, roughly speaking, the opposite set of incentives that banks operate on:

- Where banks are obsessed with quarter-by-quarter profitability, fintech companies are focused on growth, usually at the expense of short-term profitability (or even reasonable unit economics).

- Where banks are concerned with protecting their reputations with existing stakeholders, fintech companies are thinking about how to build their reputations, often by telling a story to the market about how they “democratized” access to financial services for a group that had been wrongly excluded by banks.

- Where banks are directly subject to the laws governing which customer segments they are allowed to work with, fintech companies are instead subject to their bank partners’ (usually conservative) interpretations of those laws, which they often push them to loosen up on.

Fintech companies’ incentives on these questions produce a force that counterbalances the constraints imposed by these questions on banks, which, in effect, serves to pull the financial industry into the future.

If the bank framework can be thought of as a Bermuda Triangle, then the fintech equivalent can be thought of more as a Flux Capacitor:

And this brings me to my last question:

Where Are We?

For the past couple of decades, fintech companies have been slowly chiseling away at the financial industry’s reluctance to serve specific customer segments. Where have fintech companies made the most progress? And where do we, as an industry, still have a ways to go?

Here are a few quick thoughts:

Making Progress:

- Fintech. I’m a bit less bullish on BaaS than the average fintech analyst, but it’s undeniably true that banks have come a long long way in their acceptance of and support for fintech. It’s a BaaS wonderland out there right now!

- Crypto. Perhaps fintech paved the way, but crypto and web3 companies have made remarkable progress in a relatively short amount of time gaining support from licensed banks; whether it’s new, crypto-native banks navigating regulatory hurdles (Anchorage Digital) or long-time BaaS banks investing more in crypto or traditional banks becoming more comfortable with the asset class through partnerships with infrastructure companies like NYDIG.

- Small businesses. This was one of the first customer segments targeted by fintech companies and the pressure that early disruptors like Kabbage put on banks has opened up a number of new fronts in the war for small businesses, including B2B payments and corporate cards and spend management.

- Short-term Lending. Between the end of overdraft protection (as we know it today) and the rise of pay-in-4 BNPL, we are teed up to see a lot of innovation in the short-term lending space over the next 5 years. I certainly have some concerns about this area, but, on the other hand, basically everything is better than payday lending.

- Kids & Teenagers. Banking for kids and teenagers is now a thing thanks to Greenlight, Step, Copper, Till, and a host of others. Banks — JPMorgan Chase being the most prominent example — are starting to respond to this trend as well.

- Gambling. This one is still a bit scary, but as legal restrictions around gambling continue to loosen (particularly for sports betting) opportunities are multiplying for banks that can figure out how to safely serve these businesses. Some banks, like MVB Bank, already are.

- Cannabis. Also still quite scary to banks, as my Workweek colleague unfortunately discovered, but we’re making progress here as well. Take a look at Valley Bank, Lead Bank, and Needham Bank for some early proof points.

A Ways to Go:

- Formerly-incarcerated Consumers. There are roughly 600,000 people released from U.S. state and federal prisons every year and only one bank or fintech company that I know of (Stretch) explicitly trying to help them.

- Older Consumers. Theo Lau wrote brilliantly about this problem two full years ago for Fintech Takes and I gotta say — I’m still not seeing enough investment from banks and fintech companies in this segment.

- Adult Entertainment. In my initial tweet asking about underserved customer segments, I used the word “squeamish” to explain banks’ reluctance. Some folks on Twitter objected to my use of that term, pointing out that in a lot of cases that reluctance stems more from legal requirements than from the bank’s sense of propriety. Fair! However, in the case of adult entertainment, a lot of what I see from banks can only be described as squeamishness.

- Freelancers & Gig Workers. There are neobanks targeting freelancers and digital entrepreneurs. There are even fintech companies building employment benefits platforms for these segments. However, I think the amount of investment and activity in this space pales in comparison to what we will eventually need when the macro shifts that we are seeing around the nature of employment fully play themselves out.

- Immigrants. This falls into the same ‘we’re not doing enough relative to the size of the problem’ category. I love what Fair is building. Same for Nova Credit and Stilt and a bunch of others. However, there are nearly 45 million immigrants living in the U.S. More is needed.