I’ve written about the Goldilocks Theory of financial industry analysis before – the most interesting stuff to study, the stuff that actually tells you something about the future of the industry as a whole, is the stuff in the middle – not too big, not too small.

It’s why I find large regional banks so interesting:

This is the sweet spot. Not so small that they can’t (in theory) catch up and start delivering customer experiences comparable to the national banks and fintech companies. Not so big that they can keep making strategic mistakes and survive.

I’m obsessed with large regional U.S. banks. These are the companies that have the most to gain (or lose) by making (or not making) the right decisions in response to the growth of fintech. Their strategic priorities tell us, better than anything, where fintech is truly having an impact.

This same logic applies to automobile lending.

Big enough (in both loan size and term length) to be meaningfully impacted by larger macro forces but not so big as to be completely distinct from the rest of consumer lending (in contrast to mortgage lending, which is massive and special and weird, in ways all its own).

Auto lending is really interesting!

So let’s break it down – the U.S. consumer auto lending industry – how it works, what’s been happening lately, and what might happen in the future.

How Auto Lending Works

Auto loans are secured installment loans, with terms typically between 24 and 60 months (2-5 years). The loans are secured against the vehicle itself, meaning that the lender retains the right to repossess the vehicle from the borrower if they default on their loan. (Note – this is a worst-case scenario for most lenders since the value of the repossessed car almost never covers the value of the loan. Lenders go to great lengths not to repossess cars … unless they’re Wells Fargo.)

There are a few key variables that matter for auto loans – the cost of the vehicle, the amount of money the customer can pay upfront, the interest rate, and the loan term.

The cost of the vehicle (factoring in any rebates or incentives that the vehicle manufacturer is offering) minus the money the customer is paying upfront (cash down payment plus the value of the vehicle they’re trading in, if they are) gets you the loan amount. Typically, lenders will want the loan amount to be at least slightly less than the value of the vehicle. This is known as the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, and it protects the lender’s downside if they have to repossess the vehicle and sell it at auction. A safe LTV ratio is around 70%. An outrageously high but still realistic LTV ratio is about 120% (meaning that the loan amount is 20% higher than the value of the car … lenders that lend at this level don’t tend to last long).

The interest rate is determined by looking at the customer’s ability to pay (what is their debt-to-income ratio, factoring in this new auto loan?) and willingness to pay (consumers with FICO scores between 781 and 850 are considered super prime, 661-780 is prime, 601-660 is near prime, 501-600 is subprime, and 300-500 is run-away-screaming-into-the-darkest-night deep subprime). The loan term and the interest rate determine the customer’s monthly payments. This is a delicate dance for the lender – shorter terms are lower risk, but they also generate less revenue, and they are often unaffordable for customers. Longer terms are easier for customers to pay, and they generate more revenue for the lender, but they are also riskier.

The vast majority (roughly 80%) of new vehicle purchases are financed by auto loans. For used vehicles (which are obviously less expensive than new ones), the rate of financing is less but still significant (40%). However, the used vehicle market is also substantially larger than the new vehicle market, so overall, loans for used vehicles make up more than 60% of the total consumer auto lending market.

The financing is provided by a number of different companies, including banks, credit unions, specialty finance companies, and captive auto finance companies. The captives are the financial services arms of the big car manufacturers – Ford, GM, Toyota, BMW, etc. – and they exist to help their parent companies move inventory by solving financial services challenges for automobile dealerships and their customers.

Many (though not all) consumer auto loans end up being packaged and sold as asset-backed securities to investors on the secondary market. This is a key source of liquidity for auto lenders, especially banks and specialty finance companies.

OK, that’s almost everything you need to know about how auto lending works. Just one last thing …

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

A Quick Primer on How Auto Loans are Distributed

From a distribution standpoint, there are two types of auto lending – direct and indirect.

Direct auto lending is when a consumer goes to a lender (typically a bank or credit union) directly to get a loan. This is fairly uncommon (usually only representing 10% to 20% of total auto lending volume).

Indirect auto lending is where most of the volume is. This is when a consumer gets a loan through an auto dealership as part of the process of shopping for and purchasing a vehicle. Think of it as an analog form of embedded lending – towards the end of the vehicle purchasing process; the consumer is sent to the dealership’s finance and insurance (F&I) office. The F&I office works with the customer to arrange a loan that will meet their requirements (affordable monthly payment, acceptable interest rate, etc.) and generate some revenue for the dealership (we’ll cover this in more detail later). If you’ve been through this process personally, you know that it’s often agonizingly long and filled with a lot of administrative work and constant cross-selling (insurance, ski racks, protective waxes, etc.). It’s horrible, and yet, almost all of us do it.

Here’s what’s happening behind the scenes with indirect auto lending.

The person in the F&I office at the dealership logs in to their lending portal on their computer. The two dominant lending portals in U.S. indirect auto lending are Dealertrack (founded in 2001) and RouteOne (founded in 2002). They connect auto dealerships with networks of lenders, who essentially bid on each new customer that the dealerships submit for financing.

The dealership supplies the details on the customer (name, address, SSN, vehicle they intend to purchase, loan amount, etc.), and the lenders evaluate the customer’s creditworthiness and return their best offers to the dealership, all in real time while the customer is sitting on the other side of the desk in the F&I office, sipping some truly terrible coffee.

The lender that supplies the best loan offer wins the business, but the definition of ‘best’ can be very slippery. If the customer buying the car has a high FICO score, ample income, and a low tolerance for excessive interest rates, the best offer is usually a combination of fast (this customer will walk out if the dealer keeps them waiting) and low cost (this customer is rate sensitive and knows what their FICO score entitles them to). On the other hand, if the customer has a near-prime FICO score and seems especially desperate to get the car, the best offer might be whatever approved offer is most profitable for the dealership.

Dealerships make money by arranging financing for the borrower and getting either a referral fee or profit participation in the loan from the lender, which gives them quite an incentive to take an active hand in steering customers’ financing choices. Indeed, in recent years, lending and insurance have driven more profits per new vehicle for dealers than the sale of the vehicle itself.

The best indirect auto lending customers are the ones that sit in the middle of this spectrum. Creditworthy enough to receive lots of offers from very interested lenders but not price sensitive enough to notice or care if they’re paying an above-market rate.

The Current State of Auto Lending

So, what’s going on right now in auto lending?

Here’s the data snapshot:

(Note – these stats were sourced from a bunch of different places, including Experian’s wonderful State of the Automotive Finance Market report, a report from the New York Fed, a report from TransUnion, and this story from Bloomberg.)

- Total Consumer Auto Loan Debt Outstanding: $1.52 trillion in Q3 2022, up from $1.44 trillion in Q3 2021.

- Origination Volume: Q2 2022 origination volume was down 14.9% YoY from Q2 2021, largely due to a lack of vehicle supply.

- Average Loan Amount (as of Q3 2022)

- New: $41,665

- Used: $28,506

- Average Interest Rate (as of Q3 2022)

- New: 5.16%

- Used: 9.34%

- Average Loan Term (as of Q3 2022)

- New: 69.7 months

- Used: 68.1 months

- Average Loan Payment (as of Q3 2022)

- New: $700/month

- Used: $525/month

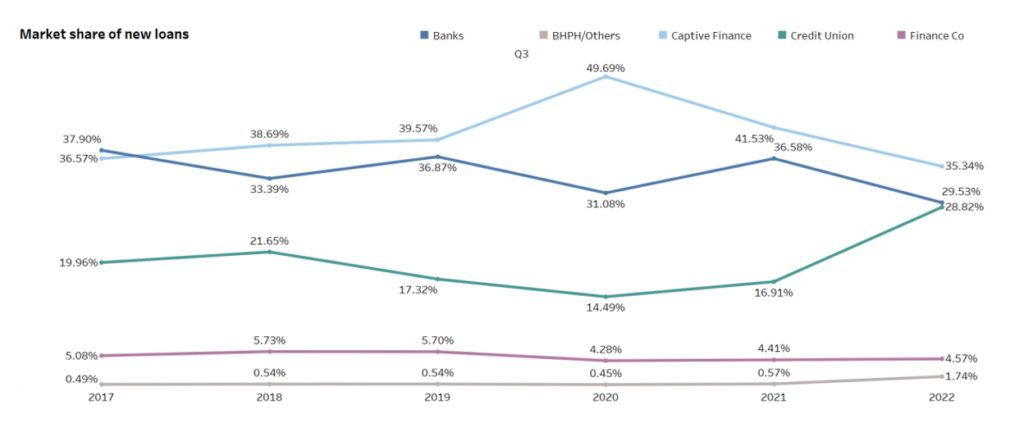

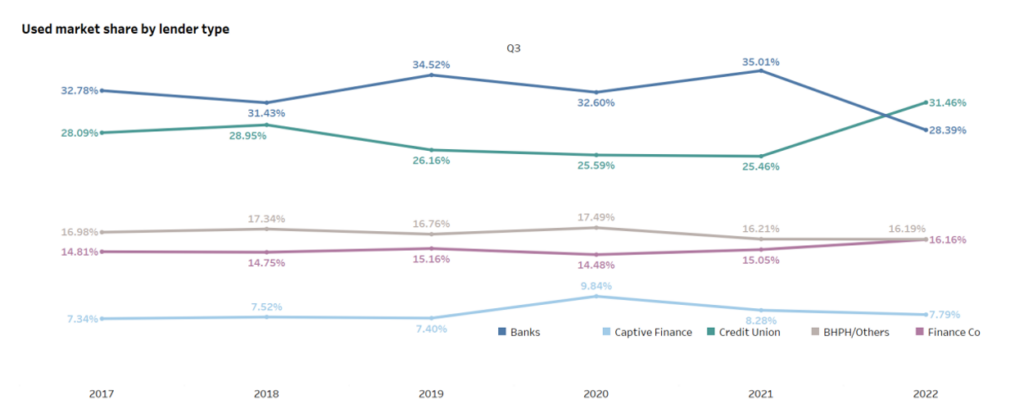

- Lender Marketshare (as of Q3 2022)

- New: Captives maintain the number one spot, but credit unions are coming on strong.

- Used: Credit unions have taken over the top spot.

- Delinquency Rate (as of Q3 2022)

- New Vehicle, 60 Days: 0.48%

- Used Vehicle, 60 Days: 1.17%

- Secondary Market Volume: Nearly $60 billion worth of ABS backed by auto loans were sold in Q1 of 2022. I couldn’t find more recent data, but I imagine that sales cooled off substantially in the last three quarters of 2022 due to rising delinquencies.

TL;DR: Consumers continue to take on record-breaking levels of auto debt, taking out larger loans at higher interest rates and for longer terms, but overall origination volume fell due to a lack of vehicle supply, and lenders and secondary market investors are getting a bit nervous about delinquencies.

And here’s the full story:

The auto lending industry has been a frustrating, lurching, expensive, volatile, profitable mess for the last three years, and it’s going to take a while before things really get back to normal.

Allow me to explain.

One model for understanding how auto lending works is to look at the incentives and behaviors of the four main participants in the auto lending industry. Those are:

Manufacturers: These are the companies that make the vehicles (Ford, Toyota, Volkswagon, etc.) As I mentioned above, all the big manufacturers have their own captive financial services divisions, which exist to help sell their own company’s vehicles through third-party dealerships. To do this, the captives offer a bundle of different services to dealerships, including floor financing (loans that help dealerships maintain a full inventory of vehicles), rebates and other incentives on specific vehicle models, and consumer loans (including 0% interest loans for well-qualified buyers). The captives’ primary incentive is to “move metal” (i.e., sell inventory) as quickly as possible, but it should also be noted that these divisions have become profit centers for manufacturers in recent years (in 2019, Ford Credit was responsible for over half of Ford Motor Company’s profits).

Dealerships: A combination of independent businesses and franchises, dealerships are the point of sale for the automotive industry. They control the customer relationship. Most dealerships will specialize in certain brands and will work with different sets of partners to facilitate financing. Dealerships’ primary incentive is to sell vehicles to consumers, but as noted above, dealerships have, in the last couple of years, been generating more profit from arranging the financing than they have by selling the vehicles. This has led to some not-great (possibly illegal) behavior recently:

Car buyers say they are hearing from dealers that cash and financing from outside the dealership aren’t welcome. Dealers tried to get some of them to finance by quoting higher prices for cash sales or refusing to sell if they couldn’t arrange the financing, according to interviews with buyers.

[The Texas Office of Consumer Credit Commissioner] has received several dozen complaints from buyers who say they were pressured to use dealer-arranged financing, many after Dallas news station WFAA ran a report on the topic last summer. The office has been investigating the claims. Texas law prohibits dealers from charging different prices for vehicles based on payment methods.

Auto dealerships are also a weirdly powerful lobbying force in Washington D.C., as senior Democratic Senators found out in 2010 while trying to pass Dodd-Frank:

[The 2007 financial crisis] led to a crackdown on Wall Street lending practices — but lawmakers made a very deliberate decision not to include auto dealers in new regulation.

The Wall Street reform bill passed in 2010 excluded auto dealers from the purview of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. While the bureau regulates auto lenders, the dealers — who connect car buyers with the lenders — are overseen by the Federal Trade Commission. Consumer advocates say the resulting ripoffs are a fairly predictable result of the car dealer carveout.

Auto dealerships have also quietly had an enormous influence over the last 40 years on the laws governing the sale of automobiles at a state level. Believe it or not, every state in the U.S. has at least some legal restrictions on the ability for consumers to purchase automobiles directly from manufacturers rather than from third-party dealerships, which is among the most subtly insane things I learned this week.

Lenders: As covered above, these are the companies that are originating, funding, and holding and/or selling the loans. Most large consumer lenders do at least a little bit of auto lending, with some, like Ally (formerly General Motors Acceptance Corporation), specializing in it. Community banks do some as well, although most tend to focus most of their resources on commercial lending. Credit unions have slowly but surely grown into giants in the auto lending market thanks largely to their willingness to offer lower interest rates in a rising rate environment. The captives are big players as well, almost exclusively on the new car side of the market. And then, there are specialty finance companies (e.g., Westlake Financial) and Buy Here Pay Here (BHPH) providers (basically dealerships that do lending in-house for subprime borrowers). Lenders’ primary incentive is to originate auto loans that fit their specific risk/return profiles and, as with all lending products, profitability is the end result of cost-effective customer acquisition, accurate credit risk evaluation, and effective liquidity management, both pre-origination (managing funding costs) and post-origination (managing portfolio risk and secondary market sales).

Consumers: And last but not least, there’s us – the buyers. Automobiles represent an interesting category of consumer spend. They are wildly expensive, both to acquire and to operate and maintain. They are an economic necessity for many consumers and an economic aberration for a small few (ask ChatGPT to define what a Veblen good is using cars as an example). They’re fun and dangerous and probably way too central to our sense of identity. All of this is to say that consumers’ incentives, when it comes to automobile lending, are difficult to parse. Demand tends to be consistently strong, but affordability definitely has an effect on both the division of demand between the new car market and the used car market and the length of time a consumer will wait before buying a new car (the average is about 7 years, but that’s a noisy number).

In this model, you can think of these four participants as overlapping lines on a cardiograph. When the auto lending market is in sync and functioning as expected, the lines are all perfectly aligned.

Of course, there are external factors that affect the shape of the line. A recession might negatively impact consumers’ ability to buy new cars, but all the market participants will react in a (mostly) synchronized fashion to adjust – lenders will tighten up their credit policies, dealerships will prepare for a slow couple of quarters, and manufacturers will ease back on production. But the market itself generally stays in sync.

Unless, that is, you hit the market with a baseball bat.

COVID-19’s Impact on Auto Lending

The pandemic and its immediate aftermath threw the auto lending market into complete chaos.

Over the last three years, we’ve had:

- Lockdowns, which drove a massive but temporary surge in the usage of digital products and services and a corresponding dip in the usage of in-person products and services.

- Stimulus checks, which temporarily boosted the personal balance sheets of tens of millions of consumers, particularly lower-income consumers.

- Supply chain disruptions, which have made buying things with all that extra money frustratingly difficult or, in some cases, impossible.

- Inflation, which has been making a lot of things more expensive and rapidly depleting whatever extra money consumers had in their bank accounts.

- Rising interest rates, which are raising the costs of borrowing money for both consumers and businesses, and causing companies to cut back on spending, including on headcount.

- The beginning of a credit cycle downturn, which is making lenders nervous and causing them to provision more money for credit losses and shrink their credit boxes.

The auto lending industry could have adapted to one or two of these disruptions, but dealing with all of them is proving to be too much to handle gracefully.

Consumer demand for automobiles surged during the pandemic, which would normally have been great news for the industry, except that manufacturers were completely hamstrung by a global chip shortage and were unable to put enough new vehicles on lots. This only served to further stoke consumer demand and create an unprecedented spike in demand for used vehicles. This spike, along with consumers’ temporary inability/unwillingness to go out in public, also created an opportunity for disruptive digital car shopping services to grow and establish their brands.

This put dealerships in an interesting position. On the one hand, they couldn’t (and still can’t) come anywhere close to acquiring enough inventory to satisfy customer demand. On the other hand, they can charge a premium for the inventory that they do get their hands on, and they can extract especially extravagant financial incentives from lenders for arranging financing for those few lucky borrowers.

And speaking of lenders, it’s been an up-and-down few years for them! Early on in the pandemic, lending conditions were great. Deposits were plentiful, delinquencies were low, and consumer demand was strong. The only trouble was acquisition. There weren’t enough vehicles to go around and, thus, there weren’t enough auto loans to go around either (and the ones that were available were being priced at a premium by dealerships that knew they had lenders over a barrel).

Now, just as the inventory shortage has started to abate a bit, lenders are faced with consumers who are still eager to buy vehicles but may not be able to afford them anymore due to a combination of still-high prices and degradation in their personal balance sheets, thanks to inflation and the negative effects of the Fed’s interest rate raises. And, oh yeah, higher interest rates also mean that bank lenders will have to start paying more for their deposits, so they won’t even generate as much profit on the loans that they would still feel comfortable making while staring into the coming credit cycle downturn.

In short, everything is out of sync.

When exactly will the market get back in sync?

I have no idea (and I doubt anyone else does, either). This is unprecedented stuff.

My best guess is that everything will start to get back to normal once the chip shortage is sorted. Insufficient supply is warping the incentives of everyone in the value chain and making it impossible for the market to find its level.

That said, no one seems to know when the chip shortage will end. It looks likely to persist through 2023, and even if it is better by 2024, the knock-on effects of inflation and a credit cycle downturn will push normalcy out by at least an additional couple of years.

Disrupting the Auto Lending Industry

Let’s wrap up by talking about the long-term future of auto lending and the potential for it to be disrupted by tech companies.

When I asked on Twitter and LinkedIn for suggestions about what to cover in this essay, fintech disruption was a popular reply. And it makes complete, intuitive sense why. Auto lending feels like an industry that is begging to be disrupted. $1.5 trillion in debt outstanding, behind only mortgage and student lending in terms of market size in consumer lending. And, let’s just be honest, the experience kinda sucks. Anyone who has ever even attempted to shop for a car at a dealership likely has multiple stories to share with you about how antiquated and inconvenient it was.

Disruption feels inevitable.

And there are plenty of tech companies that agree and that are working to manifest it. One, in particular, is worth drilling into – Carvana.

Carvana (founded in 2012) is a digital used car retailer and purveyor of car vending machines. The company went public in 2017, but it really hit its stride in March 2020 when, in response to COVID-19, it introduced touchless delivery and pick-up. In Q2 of 2020, the company reported a 25% increase in vehicle sales, and for the entire year, Carvana sold 244,111 vehicles and posted an annual revenue of $5.587 billion. In 2021, Carvana was named to the Fortune 500 list (one of the youngest companies ever to be named), and its stock price hit a high of $370.10 per share.

Then things started to turn. The company took on tons of new debt in order to continue aggressively growing the business, including through acquisitions. But in 2022, sales growth stalled out and the company’s inventory shrank and lost value as the used car market bubble started to deflate, and rising interest rates hampered both consumers’ ability to purchase and Carvana’s ability to raise debt capital and sell loans on the secondary market. In response to these challenges, Carvana laid off 4,000 workers (nearly one-fifth of its total workforce), with CEO Ernie Garcia III explaining, “we failed to accurately predict how this would all play out and the impact it would have on our business.” Carvana’s current stock price is $7.02 per share, which marks a 98% decrease from its all-time high.

The obvious parallel here is B2C fintech – 10-ish-year-old companies benefiting from a temporary surge in the usage of digital products and services and raking in huge sums of outside investment to supercharge growth, only to realize that costs had spiraled out of control and the macroeconomic tailwinds had suddenly turned into headwinds.

That’s the obvious analogy (and the most relevant one for a fintech newsletter), but I don’t think it’s quite right. Carvana certainly bears some resemblance to companies like Robinhood and Klarna (failed to control costs, fooled themselves into thinking consumers’ behavior was shifting faster than it actually was, etc.), but I think Carvana has a more fundamental problem – I don’t think Carvana’s long-term vision for replacing the traditional dealership experience with a mostly digital, completely self-service car buying experience is realistic.

It’s easy to hate on automobile dealerships, but you know what? They work. And they work especially well for new car sales, which is the lucrative, finance-laden tail that wags the dog in the automotive industry. They satisfy consumers’ contradictory desires for instant gratification (when I hand over the money, I get the car) and reassurance (before I spend this huge amount of money, I want to test the product extensively) in a way that no other model for buying and financing a new car does.

I know it feels like dealerships can and should be disrupted, and I know investors have poured a lot of money into trying to validate that feeling, but over the last couple of years, such feelings have gotten us into trouble. A good example (and a better analogy for understanding the challenge of disrupting the car buying and financing experience) is instant grocery delivery:

In the past few years, a spate of instant-grocery start-ups with names like Gopuff, Getir, Buyk, and Fridge No More have hoovered up billions of dollars in venture investment. They’ve spent these windfalls lavishly—opening hundreds of new warehouses, poaching executives from Amazon and Uber, adding new product categories, and hiring a standing army’s worth of new staff, all in an attempt to become the One True Deliverer of, say, a couple pints of ice cream, a six-pack, and that one ingredient you forgot to buy for the new recipe you’re trying out. The companies flourished amid a surge in pre-vaccine demand for grocery delivery, bolstered by the apparent belief that growth would continue even as the pandemic waned. But according to a story earlier this week in Bloomberg, that theory hasn’t panned out for these companies any more profitably than it did for their predecessors—some are shutting down, others are looking for cash infusions or buyers, and the ones that are trying to stick it out, such as Gopuff, are doing rounds of layoffs and closing warehouses they just paid to set up in order to preserve cash.

Pandemic or no pandemic, delivering highly perishable goods to millions of people, often with the promise that those goods will arrive in as little as 15 minutes, has proved a very tricky business: The unit economics are bad, the margins are bad, and the logistics infrastructure necessary to make the actual service function, even unprofitably, is extraordinarily complicated (bad). At base, these app-based, Silicon Valley–hyped start-ups keep running into two very inescapable IRL limitations: space and time.

None of this is to say that technology won’t continue to disrupt and improve elements of the car buying and financing process. It absolutely will! Specifically, within fintech, I’m excited to see innovation focused on electric vehicles (lending, insurance, infrastructure for charging, etc.) and on some of the less-sexy back-office parts of the value chain (floor financing, collections, etc.)

I’m just skeptical that dealerships will disappear anytime soon.