I was planning to write about something else this week, but then this happened:

Silicon Valley Bank, Santa Clara, California, was closed today by the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation, which appointed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as receiver. To protect insured depositors, the FDIC created the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara (DINB). At the time of closing, the FDIC as receiver immediately transferred to the DINB all insured deposits of Silicon Valley Bank.

All insured depositors will have full access to their insured deposits no later than Monday morning, March 13, 2023. The FDIC will pay uninsured depositors an advance dividend within the next week. Uninsured depositors will receive a receivership certificate for the remaining amount of their uninsured funds. As the FDIC sells the assets of Silicon Valley Bank, future dividend payments may be made to uninsured depositors.

It’s a big deal. So, we’re gonna talk about it – what happened, what might happen next, and what this all means.

What Happened?

In taking possession of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI) cited concerns about both “inadequate liquidity and insolvency.”

Let’s focus on the inadequate liquidity.

The first part of this story is about deposit inflows.

During the pandemic, banks were flooded with deposits. According to an analysis from Tom Michaud at KBW, commercial banks in the U.S. pulled in $2.4 trillion more in deposits between 2019 and 2022 than they were expecting:

And the question that every bank had to deal with over the last three years was, what do we do with all those extra deposits?

Ideally, you’d want to loan them out. But there’s only so much demand for loans (especially over the last couple of years), so most of it went elsewhere, as Marc Rubinstein at Net Interest noted:

With loan demand weak, only around 15% of that volume was channelled towards loans; the rest was invested in securities portfolios or kept as cash. Securities portfolios ballooned to $6.26 trillion, up from $3.98 trillion at the end of 2019, and cash balances went up to $3.38 trillion from $1.67 trillion.

(Sidenote – Banks can choose to designate their securities as either “held-to-maturity” or “available-for-sale.” HTM securities don’t get marked-to-market, and their value doesn’t show up on banks’ balance sheets while AFS securities do, which means that banks generally prefer to classify their securities as AFS when the value of those securities is positive and HTM when the value is negative. Since the Fed began aggressively raising rates, the unrealized losses on banks’ securities portfolios surged, and many of them were reclassified as HTM. You can read about this in a great deal more detail in Marc’s excellent write up.)

Now, of course, different banks took slightly different approaches. JPMorgan Chase (JPMC) retained a lot of cash and aggressively accounted for the securities that it did buy. It also, obviously, has a large lending business that it was able to deploy capital to.

SVB took basically the opposite approach. It specialized in serving startups and tech companies, a market that saw its own surge in deposits over the last couple of years, as the company itself noted in a recent 10-K filing:

Much of the recent deposit growth was driven by our clients across all segments obtaining liquidity through liquidity events, such as IPOs, secondary offerings, SPAC fundraising, venture capital investments, acquisitions and other fundraising activities—which during 2021 and early 2022 were at notably high levels.

All told, between the end of 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, the bank’s deposit balances more than tripled. And compared to most banks, SVB was extremely limited in its ability to deploy deposits as loans (tech startups don’t need a lot of loans, and they aren’t always the most qualified borrowers). So they deployed them to purchase securities. At the end of 2022, SVB had roughly $74 billion of loans and $120 billion of investment securities. And most of those securities ended up being classified as HTM rather than AFS:

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

On a cost basis, the shorter duration AFS book grew from $13.9 billion at the end of 2019 to $27.3 billion at its peak in the first quarter of 2022; the longer duration HTM book grew by much more: from $13.8 billion to $98.7 billion. Part of the increase reflects a transfer of $8.8 billion of securities from AFS to HTM, but most reflected market purchases.

So by the fall of 2022, SVB was sitting on a massive unrealized loss in its securities portfolio, a loss that, if it was marked-to-market, would have exceeded the tangible common equity of the bank.

None of this should have been a problem. The “loss” on these securities was a function of the change in interest rates and the fixed-rate nature of the bonds, not a commentary on the value of the underlying assets (mostly standard mortgages and treasuries). SVB could have just ridden it out.

Unless it suddenly needed money.

The second part of the story is about deposit outflows.

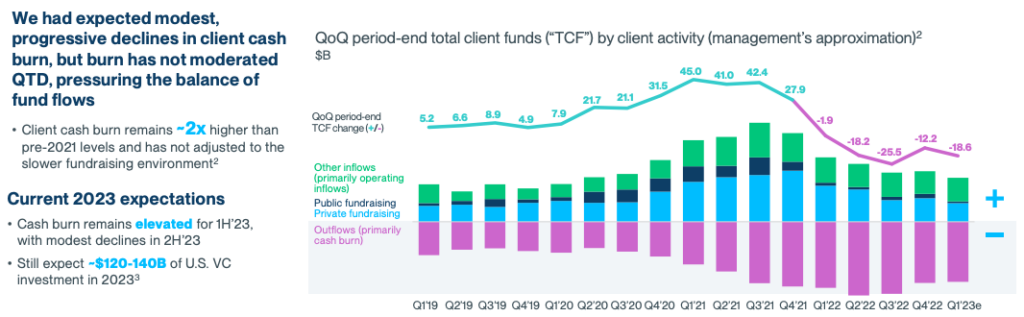

From March 2022 to December 2022, deposits at SVB decreased from $198 billion to $173 billion. That is a huge decrease, and it’s attributable to factors that are common across all banks (in a rising rate environment, depositors tend to move their money more frequently in search of higher yields) and factors that are specific to SVB (tech startups aren’t going public or raising huge rounds from VCs anymore, but they’re still spending money). This graph from SVB sums up the dire nature of its deposits situation:

In order to be able to accommodate these deposit outflows, SVB sold $21 billion of AFS securities. This loss (roughly $1.8 billion after tax) required the bank to raise new capital, which it attempted to do earlier this week:

We have … commenced an underwritten public offering, seeking to raise approximately $2.25 billion between common equity and mandatory convertible preferred shares. As a part of this capital raise, General Atlantic, a leading global growth equity fund and longstanding client of SVB, has committed to invest $500 million on the same economic terms as our common offering.

This might have worked … if everything had just held steady.

The third part of this story is about Twitter.

If you haven’t been on Twitter much in the last 48 hours, first, well done. And second, you might be surprised by the speed with which SVB went from trying to calmly raise money (Wednesday) to being taken into receivership by the FDIC (Friday morning).

If you have been on Twitter during that time, your reaction to this whole sage might mirror my friend Zach’s reaction:

Indeed. Holy shit.

The tech ecosystem, for better and (often) for worse, is a very small, interconnected, extremely online universe. When rumors started swirling about problems at SVB, people started sending suggestions:

Dozens of GPs are advising portfolio companies to take money out of SVB,TechCrunch learned from several sources. Founders Fund, Valor Equity, Inspired Capital and Hustle Fund are among the firms that have sent guidance to their portfolio companies.

One source forwarded an email to TechCrunch that Hustle Fund sent to all portfolio companies, in which co-founder and general partner Elizabeth Yin said that she “does not want to create panic” but did recommend First Republic Bank, Mercury Bank and Series Financial (which is one of their portfolio companies) to founders looking to spin up new bank accounts. In the memo, Yin wrote that the firm learned of other VCs encouraging portfolio companies who bank with SVB to move cash, which triggered them to send a note to startups as well.

Or, as Matt Levine more colorfully put it:

nobody on Earth is more of a herd animal than Silicon Valley venture capitalists. What you want, as a bank, is a certain amount of diversity among your depositors. If some depositors get spooked and take their money out, and other depositors evaluate your balance sheet and decide things are fine and keep their money in, and lots more depositors keep their money in because they simply don’t pay attention to banking news, then you have a shot at muddling through your problems.

But if all of your depositors are startups with the same handful of venture capitalists on their boards, and all those venture capitalists are competing with each other to Add Value and Be Influencers and Do The Current Thing by calling all their portfolio companies to say “hey, did you hear, everyone’s taking money out of Silicon Valley Bank, you should too,” then all of your depositors will take their money out at the same time.

(Sidenote – there is some nuance here. I think that VCs have a responsibility to their portfolio companies and their LPs to warn when a bank run might be happening and suggest that their companies get their money out while they can. I also think that VCs who took this opportunity to promote an SVB competitor that also just so happened to be one of their portfolio companies are going to end up in the Bad Place.)

Anyway, the damage was done, and Silicon Valley Bank, like Silvergate Bank before it, was finished. Matt Levine summarizes the situation well:

if you were the Bank of Startups, just like if you were the Bank of Crypto, it turned out that you had made a huge concentrated bet on interest rates. Your customers were flush with cash, so they gave you all that cash, but they didn’t need loans so you invested all that cash in longer-dated fixed-income securities, which lost value when rates went up. But also, when rates went up, your customers all got smoked, because it turned out that they were creatures of low interest rates, and in a higher-interest-rate environment they didn’t have money anymore. So they withdrew their deposits, so you had to sell those securities at a loss to pay them back. Now you have lost money and look financially shaky, so customers get spooked and withdraw more money, so you sell more securities, so you book more losses, oops oops oops.

What Happens Next?

We’re obviously still sorting through the rubble, but here are a couple of takeaways:

Depositors

The vast majority of SVB’s deposit accounts were business accounts for VC-backed startups. This means that most of the accounts had way more than the FDIC-insured limit of $250,000 in them, as Marc Rubinstein points out:

In aggregate those customers with balances greater than this account for $157 billion of Silicon Valley Bank’s deposit base, holding an average of $4.2 million on account each. The bank does have another 106,420 customers whose accounts are fully insured but they only control $4.8 billion of deposits. Compared with more consumer-oriented banks, Silicon Valley’s deposit base skews very heavily towards uninsured deposits. Out of its total $173 billion deposits at end 2022, $152 billion are uninsured.

This will be devastating for depositors, many of whom have been unable to get all of their money out and are now facing dire consequences:

Ciara May, the St. Louis-based founder of the hair care company Rebundle, had just landed in Atlanta last night when she started receiving frantic emails from investors about SVB. She’s been with the bank since 2020, and it’s the only bank her company uses; there’s more than $250,000 in the account, she said. By the time she landed, branches were shut, and wiring thousands of dollars isn’t something one can do over the phone.

Her investors introduced her to a banker who, as of this morning, is trying to help her shuffle her company’s money into a new bank, “but now I’m being told it might be too late,” she said.

She said there’s so much confusion surrounding everything that she’s still unsure what to do. “I guess wires take time, like, to get anything that would be uninsured out.” Indeed, company funds of more than $250,000 within SVB are uninsured and, at this point in time, are frozen for many. May said many within her network are frantically trying to move their money, and she has no idea how business operations will work for the upcoming weeks.

“I never thought about the need to have more than one bank account for a company,” she told TechCrunch.

The FDIC’s job, starting Monday, is to cash out insured deposits and get to work selling SVB’s assets, with the goal of eventually making all depositors whole. This will almost certainly come too late for some, as one founder told TechCrunch:

Many good, responsible companies will go down, many people without jobs and founders shattered for no good reason.

SVB

In a darkly ironic twist, SVB just became big enough in 2021 for regulators to require it to draw up a “living will,” which the bank submitted for the first time in December.

This will be the resolution plan that the FDIC will be following in attempting to ensure that A.) depositors get their insured deposits back on Monday morning, B.) it generates the maximum return on the sale of SVB’s assets, and C.) it minimizes any loss for creditors (which includes the Federal Home Loan Banks, which loaned SVB roughly $15 billion).

Beyond the return of the insured deposits on Monday (which will absolutely happen), it’s a bit unclear how successful the FDIC will be in maximizing the value of SVB’s assets and making creditors (and uninsured deposit holders) whole. How much will some bank (or banks) pay for SVB’s assets? I don’t know, but I think Matt Levine’s guess is a decent one:

I am pretty sure the answer is higher than $8 billion, the amount of insured deposits: The FDIC will not be on the hook for the insured deposits. The $15 billion of FHLB advances are also quite senior and will presumably be no problem to pay back.

I would also guess — not investing or banking advice! — that the answer will also turn out to be higher than $188 billion, which is the total amount of deposits plus FHLB advances. I say this not because I have done a detailed analysis of SVB’s assets but because it seems bad for the FDIC to wind up a big high-profile bank in a way that causes significant losses for depositors, including uninsured depositors. There was a run on SVB in part because there hasn’t been a big bank run in a while, and people — venture capitalists, startups — were naturally worried that they might lose their deposits if their bank failed. Then the bank failed.

If it turns out to be true that they lose their deposits, there could be more bank runs: Lots of businesses keep uninsured deposits at lots of banks, and if the moral of SVB is “your uninsured transaction-banking deposits can vanish overnight” then those businesses will do a lot more credit analysis, move their money out of weaker banks, and put it at, like, JPMorgan. This could be self-fulfillingly bad for a lot of weaker banks. My assumption is that the FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and the banks who are looking at buying SVB all really don’t want that. If you are a bank looking at buying SVB, and you do a detailed analysis of its assets and conclude that they are worth $180 billion, and you come to the FDIC and say “I will take over this bank and pay the uninsured depositors 95 cents on the dollar,” the FDIC is going to look at you and say “don’t you mean 100 cents on the dollar,” and you are going to say “oh right yes of course, silly me, 100 cents on the dollar.”

SVB Employees

I really have no insight into what life is going to be like for Silicon Valley Bank employees next week and in the weeks to follow, but I know for a fact that these folks are held in the highest possible regard by everyone in the fintech (and broader tech) ecosystem, and I sincerely hope they land in good places.

If you work at Silicon Valley Bank and need any help finding a new role (or you’d just like to chat), please let me know.

Other Banks

Looking beyond SVB (and Silvergate), the next question we need to ask is, what will the fallout of this be for other banks?

The market, as it is wont to do, reacted negatively to the SVB news:

Regional bank stocks tumbled in the wake of Silicon Valley Bank’s demise, with the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF lost nearly 4.4%. For the week, the regional bank fund lost about 16%, its worst week since March 2020 as the pandemic hit.

Several bank stocks were repeatedly halted on Friday, including First Republic, PacWest and crypto-focused Signature Bank. First Republic dropped 14.8%, and PacWest shed 37.9%.

But that doesn’t really tell us much about the actual state of these (and other) banks. Should we be concerned that the same pattern that took down Silvergate and SVB – unrealized losses on fixed-rate securities becoming suddenly realized due to unexpected deposit outflows – impacts other banks?

This obviously shouldn’t be taken as investing or banking advice, but I don’t believe think so.

The biggest banks in the U.S., which are considered “systematically important” and are under much heavier scrutiny from regulators than SVB was, have much more diversified balance sheets and should be fine, according to Michael Barr, the Fed’s Vice Chair for Supervision:

There are obviously larger institutions that are also exposed to these risks too, but the exposure tends to be a very small part of their balance sheet. So even if they experience the same deposit outflows, they are more insulated.

Smaller banks, say those under $10 billion in assets, are more of a mixed bag when it comes to having healthy balance sheets. One metric that you want to look at with these banks is something called Tangible Equity Capital Ratio, which helps you estimate a bank’s sustainable losses before shareholder equity is wiped out. It’s a good metric to use because it takes into consideration unrealized loss positions in banks’ securities portfolios, which is obviously the thing we’re all concerned about these days.

According to an analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, at the end of 2021, only 4 community banks had tangible equity capital ratios below 5 percent. By June 30, 2022, that number had increased to 333.

That’s concerning. However, my concern is modulated somewhat by the basic reality that most banks in the U.S. aren’t going to have the same level of concentrated, high-risk deposits that SVB and Silvergate had (First Republic Bank, an SVB competitor, just publicly clarified that tech only makes up 4% of its total deposits and no sector accounts for more than 9% of total deposits).

It’s definitely something to watch carefully (and both regulators and the market will be), but it’s far from being a contagion.

Regulators

Speaking of regulators, Marc at Net Interest makes a good point:

In Europe, interest rate risk is overseen by regulators through the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). It requires banks to hold enough high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) – such as short-term government debt – that can be sold to fund banks during a 30-day stress scenario designed by regulators. Banks are required to hold HQLA equivalent to at least 100% of projected cash outflows during the stress scenario.

Credit Suisse withstood its surge in deposit outflows with an average LCR of 144% (albeit down from 192% at the end of the third quarter). Silicon Valley Bank was never subjected to the Federal Reserve’s LCR requirement – even as the 16th largest bank in America, it was deemed too small. It’s a shame. Regulation is not a panacea since banks are paid to take risk. But a regulatory framework to suit the risks of the day seems appropriate and it’s one US policymakers may now be scrambling for.

I know all banks hate dealing with regulation, and there is a definite cost to regulatory compliance that can be burdensome for smaller banks, but it sure seems like interest rate risk is one we should be stress-testing all banks on moving forward.

What Does This Mean?

This last section of today’s essay is going to be less analysis and more of a personal meditation on what all of this means, in a much broader sense, for the industry.

One of the things about the Silicon Valley Bank and Silvergate Bank stories that I do not understand is how executives at these two institutions could have possibly felt comfortable taking this level of interest rate risk.

It’s honestly insane.

Take SVB as an example. It has been around since 1983. It has seen interest rate hikes before. And as Marc at Net Interest points out, it has seen sudden and massive deposit outflows from its customer base before too:

In the aftermath of the dotcom crash 20 years ago, deposits at the bank fell from $4.5 billion to $3.4 billion by the end of 2001 as customers drew down on their cash reserves.

You know from experience that VC-backed tech startups are not stable sources of deposits. You know that. What the hell are you doing, plowing most of your capital into long-duration, fixed-rate securities?

The only answer I can come up with, and this, I think, is the same answer for Silvergate, is that they bought into their own myth.

Our deposits are perfectly stable because tech valuations/crypto prices are never going to go down!

This is magical thinking that is completely at odds with basic logic and the lived experiences of these institutions. And yet, I can’t think of any other explanation that would cause otherwise sober and analytical bank executives to take these obviously-stupid interest rate risks.

This is a symptom of a larger problem in the recent history of financial technology – the NGMI problem.

NGMI (Not Gonna Make It) is an acronym used by some in the crypto community to ridicule people who are skeptical or critical of crypto. You don’t see it much anymore, but in 2021 it was rampant. It (and similar language, like “Have Fun Staying Poor”) had this subtly corrosive effect by suggesting that people who didn’t understand or feel comfortable with crypto and its risks were suckers who were too dumb to recognize an obviously beneficial shortcut when they saw one.

And that same impulse – to believe that only fools and losers don’t take shortcuts, even when those shortcuts are clearly risky and/or immoral – has permeated the entire fintech industry.

I see it everywhere.

I see it when founders and VCs debate what the most believable interest rate for customers will be, rather than what would be the best or the safest. I see it when a stablecoin issuer opens bank accounts using falsified documents. I see it when B2C fintech companies ignore fraud in pursuit of growth. I see it when the hosts of a popular podcast casually joke about dumping inflated tokens onto retail investors. I see it when a founder says, “fuck it, we’re doing it anyways,” and launches a new product while lying about it being insured.

I’m tired of seeing this shit.

Researchers have discovered that you’re more likely to go bankrupt if someone in your neighborhood wins the lottery. Over the last three years, a bunch of folks in fintech won the lottery. And now we’re all going bankrupt.

I hope, as an industry, we can learn from this and do better.