Would you rather travel fast or travel in comfort?

If you were crossing an ocean in the late 1930s, this was an important question.

If you wanted to optimize for speed over comfort, the best choice was one of those new heavier-than-air planes from an airline like Imperial Airways or Lufthansa, which could get you from Western Europe to New york in roughly 20-30 hours.

If you didn’t mind taking your time and you could afford a ticket that was several times as expensive as an airplane ticket, an airship was the obvious choice. It would take you 2-3 days to get across the Atlantic on one of these puppies, but you were traveling in style – private cabins, observation decks, and gourmet meals prepared by a team of chefs.

This seems to me to be a fairly obvious analogy for financial services.

Banks, generally speaking, are the luxury option. They are designed for people who already have lots of money and who prefer to pay for stately (read: slow), white-glove service.

Fintech companies, by contrast, are all about speed and accessibility. They want to work with customers who can’t afford to wait around for banks. Lower-income consumers, younger consumers, and small businesses are all good examples.

Ayokunle Omojola explains this perfectly in his essay, Time to Money as a Competitive Advantage:

If you’re rich this doesn’t matter. If you live paycheck to paycheck, time to money matters a lot. Living paycheck to paycheck means you likely have a liquidity problem that can quickly turn into a solvency problem. For example, one of the highest frequency and by far the largest use case by dollars of p2p apps is paying rent. Most hourly workers get paid weekly or biweekly on fridays, and many settle rent on fridays as well, as soon as their paycheck comes in (the rent-on-fridays dynamic also surprised me because I’ve only ever seen rent paid on a monthly basis, so I’m clearly privileged here). This means that, for these consumers, before Cash App came along – they’d get paid on a friday, and either a) have to wait till the weekend was over to pay their roommate or landlord, or b)pay a lot of fees to ensure their rent was paid on time.

Many startups offering financial products first find a wedge with people who are economically marginalized, who by definition will have more volatile finances than average. Whether they’re small businesses, micro merchants, or consumers, they’re often operating paycheck to paycheck, and missing a crucial payment one day can turn a short term liquidity problem into a long term solvency problem.

As Ayo wrote, many fintech startups have found success in enabling speed for underserved, economically marginalized customer segments. None more so than his former employer, Block, creator of Cash App, which has seen an explosion in usage of its consumer product since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Prior to 2020, the merchant services side of Block’s business drove the company’s profitability. As of the end of 2019, merchant services accounted for $1.39 billion in gross profit, compared to the consumer-facing Cash App, which accounted for only $457.6 million of gross profit.

That changed during the pandemic, as many merchant businesses locked down and individuals activated millions of Cash App accounts to receive government stimulus and unemployment payments.

By the end of 2019, Cash App had 24 million monthly active users, according to the company’s Q4 letter to shareholders. By the end of 2020, Cash App reported 36 million monthly actives, which has since grown to 51 million.

The explosion of user growth resulted in higher gross profit. By the end of 2020, Cash App gross profit reached $1.2 billion, a 170% growth rate from the prior year, compared with merchant services gross profit of $1.5 billion, an 8% growth rate from the prior year.

51 million monthly active users.

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Reader: that is a lot.

Along with Chime and PayPal, Cash App is one of a handful of digital-only banks that have gained tremendous market share in the last five years, at the expense of big banks and, especially, community banks and credit unions.

However, a recent report from Hindenburg Research alleges that most of this growth and profitability isn’t legitimate:

Our 2-year investigation has concluded that Block has systematically taken advantage of the demographics it claims to be helping. The “magic” behind Block’s business has not been disruptive innovation, but rather the company’s willingness to facilitate fraud against consumers and the government, avoid regulation, dress up predatory loans and fees as revolutionary technology, and mislead investors with inflated metrics.

Spicy stuff!

I’m going to break down the Hindenburg report in a lot of detail, but first, we should answer this question – who the hell is Hindenburg Research?

Hindenburg Research

I’ll be candid, I had never heard of them until last week.

This is somewhat by design.

Hindenburg Research tries to keep a low profile. It’s a small private company, and its founder, Nathan Anderson, doesn’t do press interviews.

Instead, Anderson and Hindenburg spend their energy researching public companies that they believe have engaged in corporate fraud and malfeasance. They go through public records, internal corporate documents and talk to employees and former employees. The output of all this research is a report, which is circulated to Hindenburg’s limited partners, who, together with Hindenburg, take a short position in the target company before publicly releasing the report.

Put simply – Hindenburg Research is an activist short seller. They conduct research designed to drive down a target company’s share price and profit if the price does, in fact, decline.

Allow me to say a couple of things at this point:

- I’m not a huge fan of short sellers, as a general rule. I find activist short sellers who publish controversial research in support of their positions to be particularly concerning. The incentives for publishing something incendiary are very strong.

- On the other hand, I do think short sellers have a role to play in balancing out the ecosystem. Everyone these days is talking their book (this is depressing to me for more existential reasons … but that’s a different essay). For example, ARK Investment Management – a provider of actively-managed ETF focused on disruptive technology companies with just under $16 billion in assets under management – owns a substantial amount of stock in Block and has done a tremendous amount of work analyzing Block’s business and talking about the enormous potential of products like Cash App. I respect the research and analysis done by ARK’s fintech investors and have cited much of it in my newsletter, but I’m also not naive – they have a position they are trying to push. Cathie Wood (founder of ARK) wasn’t happy with the Hindenburg Research report on Block. In related news, it turns out that water is wet.

- I am very sensitive, in a post-Silicon Valley Bank world, to people having strongly-held opinions on topics that they are not experts in. I am not an expert in banking or financial technology, and, despite the work I do to educate myself, my opinions in this space are all very weakly held. Perhaps because of this, my reactions to other people’s strongly-held opinions on topics that they aren’t experts in tend to be quite negative (as anyone following me on Twitter recently might have noticed). I have a hunch that this will color my analysis of the Hindenburg report.

In the immediate aftermath of the release of the Hindenburg report, Block’s share price dropped 22%. In the days since – especially since issuing a rebuttal to the report – the company’s stock has recovered somewhat.

But that’s boring!

All that tells us is that most investors have no fucking clue what they’re doing.

What is actually true?

I don’t know (again, opinions weakly held!), but I do have some thoughts.

It Said – It Said – I Said

In order to parse the Hindenburg report and Block’s response to it, let’s play a game called It Said – It Said – I Said.

I will lay out the main points of the case made by Hindenburg Research, the rebuttal issued by Block (and the rebuttal to the rebuttal from Hindenburg), and my thoughts on each.

Ready?

Here we go.

Hindenburg says … Block misstates the number of Cash App customers and its customer acquisition costs.

A core issue that Hindenburg takes with Block is its methodology for counting its customers, which Hindenburg believes is deceptive:

Cash App’s number of transacting active users – or account holders that make use of 1 or more Cash App service in a given time period – is a closely watched metric. It forms the foundation of Block’s claims to have a strong network effect and ability to cross sell new products and services to its user base. The company recently reported 80 million annual transacting actives, and 51 million monthly transacting actives.

Block’s disclosures have referenced the issue of “transacting active” account metrics deviating from the number of genuine users on its platform. But its vague disclosure suggests that “transacting actives” may be mildly overstated or even understated—basically insinuating that it is a ‘wash’

We think Block simply chooses not to report more accurate user information because reporting inflated user metrics helps inflate its stock.

This deceptive math also warps another metric that Block loves to brag about:

Beyond reporting an inflated “transacting actives” metric, large numbers of duplicate and scam accounts can distort another key metric – customer acquisition costs – which Block management uses to showcase its efficiency versus traditional banks.

In March 2021, Block’s CFO Amrita Ahuja explained how Cash App acquires new users for less than $5 each

Ahuja explained that Cash App achieves this low cost due to network effects, because “a customer can bring a new customer into Cash App at little to no cost for us” by inviting them to engage in a Cash App transaction.

In May 2022, Block’s Cash App Lead Brian Grassadonia explained that while user acquisitions costs had doubled to $10, the metric still represented an advantage for Cash App over traditional banks

Hindenburg believes that Block should just report “verified users,” which it thinks are a more accurate point of comparison to the banks that Cash App competes with:

Most banks and financial services companies report metrics on actual individual users, such as number of deposit holders, because it is easy to report given the information available to them and because it makes sense.

Given that Block has these metrics available, we think it should continue to report verified user counts and individual SSNs to investors going forward—there is no reason why the company should hide its own internal, more accurate, user estimates while reporting a fluffed-up metric to investors.

Block says … most of its monthly active users are fully vetted banking customers, and the ones that aren’t are on the path to becoming fully vetted customers.

From Block’s rebuttal:

As of December 2022, Cash App had more than 51 million monthly transacting actives. Of these, approximately 44 million were connected to an identity verified through our Identity Verification (IDV) program.

Many of the remaining accounts will eventually go through IDV as they increasingly engage with the Cash App platform. Approximately 13% of the unverified accounts as of December 2022 have completed IDV so far in 2023 as of the date of this release.

The 44 million verified accounts represented approximately 39 million unique Social Security numbers as of December 2022 (we use Social Security number as a logical, unique identifier to estimate the number of identities in this analysis).

Alex says … Block’s explanation makes sense, but it is nice that Hindenburg got them to go on the record about the 44 million fully vetted customers.

The root of the issue here is that Cash App, like most P2P payment apps, employs a ‘light KYC’ strategy, which enables them to onboard users by only collecting name, email or phone, and ZIP code. This initial onboarding allows customers to get access to the basic P2P functionality (up to a limit of $1,000 in transactions within a 30-day period). If a customer wants to get access to the full Cash App experience (debit card, direct deposit, savings, etc.), then they need to go through additional identity verification steps, including sharing their full address and social security number.

To be fair to Hindenburg, this two-tiered customer onboarding process is a bit unusual compared to banks, but it’s not inherently sinister.

Think of it like a video game. Traditional banking is like playing a game with only one level, but that level features a mega-difficult boss that you need to defeat (the new customer onboarding process). By contrast, Cash App is a game with a couple of levels, each progressively more challenging, but not anywhere close to as difficult as the Bank game.

This is what leads Hindenburg to the wrong conclusion on Block’s customer acquisition costs (CAC). The first ‘level’ in Cash App’s video game is specifically designed to encourage new players to invite their friends (i.e. send someone money through Cash App), which is a brilliant strategy for driving unpaid referrals.

Overall, I would say this is an unfair hit by Hindenburg. However, I do want to give them credit for getting Block to be a little bit more transparent about the portion of customers who have gone through the full ID verification process. That’s a number I’ve been wanting to see for a while. Hopefully, Block continues to provide this level of transparency.

Hindenburg says … Block’s ID verification process (at each level of the game) isn’t nearly robust enough and that the app is a revolving door for suspicious users.

A couple of different pieces to the case here.

First is Hindenburg’s assertion that the ‘light KYC’ approach done for all new users makes it difficult for Block to keep bad users off the platform, even if the accounts associated with those users are suspended:

By basing accounts on email addresses or phone numbers, Block created a system in which users could join the platform multiple times, even after getting kicked off for fraud.

A former employee explained that getting kicked off Cash App was just a temporary problem:

“It wasn’t like, TSA’s No-Fly list. You know it was kind of like the account will get closed and then they’ll try it again and maybe get to use it for a little while longer, until, you know, maybe the next account gets closed.”

Second, Hindenburg argues that even the more rigorous second-level ID verification done by Block for users that are upgrading the full Cash App experience is ineffective:

Cash App’s Terms of Service state that users agree to provide accurate information when setting up their account, and to assure that any information added to the account is “true and accurate.”

The terms explicitly state that users “may not select a $Cashtag that misleads or deceives others as to your business or personal identity or creates an undue risk of chargebacks or mistaken payments.”

Cash App makes no mention of deceptive screen names, and it allows users to change these names and their photo in a few simple steps. Users can obfuscate their personal identity without notifying Cash App or having any changes made to the platform’s internal data.

To test this we created two Cash App accounts changed our outward facing personas to Elon Musk and Donald Trump and successfully exchanged funds.

Taking it a step further, we ordered a Cash Card under this alias to see if Cash App’s compliance would take issue with the obvious irregularity. They promptly mailed us a Donald J. Trump Cash Card.

Block says … it has a very robust compliance program.

We ❤️ compliance, apparently:

We maintain a culture of compliance and a holistic program designed to comply with a range of regulatory obligations in the markets where we operate. As disclosed in our public filings, in the U.S., we maintain a Bank Secrecy Act (BSA)/Anti-Money Laundering (AML) program in accordance with federal AML guidelines, the US Bank Secrecy Act, and the USA Patriot Act.

Our AML program is led by experts in the field and includes systems, policies, procedures, and controls designed to prevent and disrupt criminals from using our platform to facilitate money laundering, terrorist financing, and other unlawful activity. Like other financial institutions, our AML program is independently assessed on an annual basis and we are examined by both state and federal regulatory agencies.

Implementing compliance controls is an embedded part of our product development process, and we endeavor to understand potential patterns of abuse and prevent bad actors from exploiting our system. In cases where we observe vulnerabilities, we adapt and work to improve. In addition to our IDV controls described above, we maintain ongoing KYC, transaction monitoring, and suspicious activity reporting programs. We leverage in-house and third-party detection models and tools for both risk and compliance monitoring purposes, including the use of advanced machine learning techniques to identify prohibited and/or potentially unlawful activity on the platform.

Alex says … Block has some work to do here.

I find this section of the Hindenburg report to be fairly convincing.

It seems clear from the internal documentation assembled by Hindenburg and the conversations that they had with employees that Block is very aware of just how many of its blacklisted accounts have associated users and accounts that are still active on the platform. This isn’t an “ohh we had no idea” type of problem. This is a choice.

Matt Levine at Bloomberg writes frequently about the ‘dial’ that sits on the desk of every bank’s Chief Compliance Officer, which says “More Crime” on one side and “Less Crime” on the other. The job of this highly-paid executive is to, slowly over time, nudge that dial toward the “More Crime” side in order to help the business generate more revenue. And when that dial gets turned too far, and regulators get grumpy, a new Chief Compliance Officer comes in and makes a big show of spinning the dial all the way back the other way.

Fintech companies don’t really work this way. With their grow-over-literally-everything mandate, the Less Crime/More Crime dial at these companies usually gets turned all the way up to 11, and then a cloth gets thrown over the desk, and then the light is turned off, and then the Chief Compliance Officer is locked out of her office.

That seems to be, in a rough sense, what happened at Cash App over the last five years.

Also, I’m sorry, but shipping a debit card to a customer with the name “Donald J. Trump” on it is just a rookie mistake. Even if you don’t care about creating comprehensive compliance controls, just put in a hardcoded rule to automatically stop debit cards from being issued in the names of any presidents or ex-presidents. That’s just good PR.

Hindenburg says … one of Cash App’s primary customer segments is criminals.

This isn’t me exaggerating. They literally say this in the report:

Our research shows that Block has embraced a traditionally very underbanked segment of the population: criminals.

Cash App’s embrace of non-compliance begins by making it easy for users to get on the platform, easy for them to get back on the platform if their accounts are closed, and easy to remain anonymous or operate under blatantly false identities.

As one former said about signing up for Cash App:

“It’s wide open. And if I was a criminal, I would have done it.”

Another former compliance employee of a Cash App partnership told us, “every criminal has a Square Cash App account.”

The report supports this point by cherry-picking evidence that Cash App has been used to conduct illegal activities and that it is mentioned in a number of rap and hip-hop songs as a tool for facilitating crimes.

I’m going to refrain from quoting any of these passages.

Block says … illegal activity is an unfortunate fact of life for every company that provides financial services, and it takes its responsibility to fight this activity very seriously.

Block pushed back, but in a fairly non-specific way:

While people use products like Cash App to improve their financial lives, there are individuals who nevertheless seek to perpetrate fraud and other illicit activity—this is unfortunately the case across the financial services industry. Our Risk and Compliance teams and programs are built around mitigating these instances and their impact.

Building a trusted platform and combating fraudulent and other illicit activity is a top priority for Cash App and Block more broadly. Our risk models focus on typologies such as suspected stolen identities, scam payments, and potential account takeover in order to prevent potentially fraudulent transactions from occurring on the platform and to keep the platform safe for good customers. Our Compliance team also investigates, takes actions and reports cases of suspected fraud to law enforcement.

Alex says … this is gross, and Hindenburg is in the wrong here.

I’m not a fan of this.

Hindenburg made this the first section of the report. The very first section! They equated serving the unbanked/underbanked consumers with enabling criminals. They cherry-picked a few examples of illicit behavior being tied to Cash App, in both real life and in art, to paint a broader picture, a picture that has clear racist overtones.

This was a bad thing to do.

It’s also bad analysis.

It’s easy to find examples of Cash App’s usage in illicit activities because Cash App, broadly, is more visible in popular culture than most other bank and fintech products. That is not, in and of itself, evidence that Cash App is used to conduct more illicit activity in absolute terms.

Indeed, Hindenburg doesn’t even seem to understand the problem properly.

In its report, it says that “Block has embraced a traditionally very underbanked segment of the population: criminals.” This isn’t true! Criminals aren’t underbanked! The AML processes in place today at banks around the world are comically inept. They have been estimated to only stop something like 0.1% of money laundering globally, a record that would embarrass the Washington Generals.

Criminals aren’t underbanked, and that’s not Block’s fault.

Hindenburg says … Cash App facilitated a lot of fraud during the pandemic.

Continuing with the fraud theme, Hindenburg claims that Block seized a growth opportunity during the early days of the pandemic (when Block’s merchant services business was struggling) by distributing stimulus checks and unemployment insurance to consumers, a task that it engaged in recklessly:

Federal COVID relief legislation known as the ‘CARES Act” was signed into law on March 27, 2020. The law provided payments that included expanded unemployment insurance benefits for those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

One day before the CARES Act was signed into law, Dorsey tweeted that Block was prepared to help distribute government money immediately, emphasizing its focus on customers without bank accounts.

Dorsey tweeted: “the technology exists to get money to most people today (even to those without bank accounts).…US government: let us help.”

Dorsey’s Tweets urging users without bank accounts to receive government money through Cash App served as a siren song for scammers.

And, once again, Hindenburg brings rap songs into its argument:

The “Wild West” approach was once again reflected in pop culture, making the signs hard to miss.

On September 11, 2020, rapper Nuke Bizzle released a song called “EDD”, in reference to California’s “Employment Development Department”, which distributed pandemic unemployment relief.

The song focused entirely on how easy it was to steal COVID relief funds from the government, with lyrics referencing the approach of using multiple names at the same address

Block says … not much, but others jump to its defense.

Block didn’t address this one in its rebuttal, but Maximilian Friedrich of ARK did. He pointed out on Twitter that the Nuke Bizzle example used by Hindenburg is deceptive because it fails to point out the role that a traditional bank (and banking channels like the branch and ATM) played in helping to facilitate this scam as well:

What Hindenburg tells you: Cash App was “the only” electronic P2P payment processor mentioned in a COVID fraud indictment

What Hindenburg doesn’t tell you (cut out of screenshot): The defrauded funds came via Bank of America which sent the criminal $1,256,108 in PUA benefits and the vast majority of those funds obtained via BofA was cashed out using:

- ATMs: $375,177

- Bank branches: $39,180

- BofA debit cards: $205,273

“Money Transfers/Funds Transfer services” *including* Cash App were responsible for $85,130, ~7% of total or ~12% of cashed-out funds

Alex says … Block helped facilitate a lot of fraud during the pandemic, but so did everybody else, and also, concerns about fraud are a bit beside the point.

Hindenburg certainly has a lot of data to support its point. And I don’t think anyone (not even the folks at ARK) would dispute that Cash App played a central role in distributing a lot of financial aid to consumers during the pandemic, which we now know included a heck of a lot of fraud.

That said, it’s very clear that this was an industry-wide problem, which engulfed both banks and fintech companies. To the extent that it was a bigger problem at fintech companies than it was at banks, I think that’s more of a reflection of the speed and single-mindedness of fintech companies compared to banks. And that speed and single-mindedness were probably, on balance, a good thing! It was a pandemic. We feared (reasonably) that the entire global economy was about to crash and burn. We needed to get money into people’s hands quickly. Fraud wasn’t a concern.

I don’t absolve Block here, but I think it’s understandable.

Hindenburg says … low-level fraud is rampant within the Cash App ecosystem.

The report paints a rather overwhelming picture:

One former employee said their manager explained that Cash App couldn’t make money because of the costs associated with trying to contain fraud:

“I know that we were told … that [Cash App] pretty much just bleed cost based on all of the stuff that the risk team has to do to stop account take overs and all like the fraudulent Cash App scams and all of that kind of stuff that that goes on. We were told that it’s pretty much like running the heat, but with the window open.”

Another former customer service representative told us that around half of all the calls they took during a typical shift were from users they believed were trying to commit fraud, often by disputing charges on their Cash Card for goods or services they likely received:

“I’m working to weed out the 40 to 50% of fraudulent activity accounts that I’m working with daily.”

They added that not all of the fraud was organized professional criminal activity. Much was rampant low-level fraud against the platform:

“I’m not saying like all of them were hardcore gangsters, you know, but it was at the very least people buying things online and saying that they didn’t.”

Cash App frequently acquiesced, at one point automatically refunding any disputed card charge of less than $25, the same former employee told us. Representatives began to recognize users who regularly charged food deliveries to the card and then demanded their money back:

“I wish I ate as good as this girl does.’…This woman is legitimately eating lunch on us every freakin’ day.”

Another former employee told us:

“I felt like the debit card fraud, that that was kind of on a consistent path higher my entire time there.”

Block says … it has a good handle on the fraudulent activity on the platform.

From the Block rebuttal:

While it’s challenging to arrive at definitive estimates of the amount of fraud and illicit activity, we measure the number of accounts that we “denylist” (a control that prevents, among other things, sending and receiving funds, using a Cash App Card, buying stocks or bitcoin, or taking a loan). In 2022, approximately 2.4% of Cash App transacting active accounts were denylisted by our Compliance and Risk teams during that year. We have additional controls to help prevent known bad actors from returning to the platform.

Alex says … first-party fraud is the biggest problem at Cash App (and at a lot of other fintech companies).

This was among the least salacious accusations in the Hindenburg report, and yet, it was the one that most deeply resonated with me.

Last year, I wrote an essay – Fintech’s Steroid Era – in which I compared the last five years in fintech to the steroid era in Major League Baseball. It was written in response to the growth of first-party fraud in fintech, the exact type of fraud that Hindenburg is reporting that Block has been tolerating. Here is the key passage from that essay:

Why are we opposed to professional athletes using performance-enhancing drugs? I mean, it’s their careers and their bodies. If they’re willing to take the risk, why shouldn’t they be allowed to?

One of the more compelling answers to this question is that it sets a bad example. Professional athletes are role models, and we want them to encourage kids to go beyond simple utilitarian cost-benefit analyses and reach for a more virtuous ethical model. The problem with cheating isn’t that it’s against the law or that it’s going to hurt more people than it helps. The problem with cheating, put simply, is that it’s wrong.

One of the things I really don’t like about fintech’s recent tolerance for first-party fraud is the message that it sends to consumers, particularly young consumers – cheating is OK. It’s acceptable to game the system. It’s OK to lie.

This concern isn’t hypothetical. Humans have a remarkable capacity to justify almost anything to ourselves if we are provided with the proper incentives. Indeed, we can go much further than simple justification. We can convince ourselves that the bad thing we’re doing is, in fact, morally right.

I doubt that Block’s investors really give a shit about this, but whatever, I care. Block has been teaching its customers that it’s ok to cheat, and that’s bad for the future of our industry. I’m glad Hindenburg took the time to call this out in the report.

Hindenburg says … Block is circumventing the law by issuing debit cards through a partner bank.

This is my favorite ‘bombshell’ from the report:

For years Block has limited its disclosure of interchange fees to just a single line of text in its annual reports, with no numbers included:

“Square earns interchange fees when individuals make purchases with Cash Card.”

In 2022, Block’s disclosure provided little additional color:

“We also earn interchange fees when a Cash App Card is used to make a purchase” and “interchange fees are treated as revenue when charged.”

Despite Block’s opacity on the subject, an October 2022 report by Credit Suisse estimated that “spend”, a segment it said was largely made up of Cash Card interchange fees, accounted for $892 million, or ~35% of 2021 Cash App revenue.

We suspect we know the reason behind Block’s opacity on the subject.

In 2010, Congress capped interchange fees under the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act to help ensure the fees were “reasonable and proportional to the cost incurred by the issuer.” The Durbin amendment provides an exemption for small banks, i.e., when the card issuing bank has less than $10 billion in assets.

Block hardly fits that definition of “small”, with $31 billion in assets, per its most recent annual filing.

Yet the company skirts the interchange fee cap, increasing the fees on a typical retail transaction by anywhere from an estimated 1.27x to 5x, imposing that inflated cost on many of the merchants and small businesses it claims to be helping.

To qualify, Cash App selected Sutton Bank to issue its prepaid debit card. Sutton Bank is a small bank under the Durbin exemption definition and appears on the Federal Reserve’s list of “Institutions Exempt from the Debit Interchange Standards.”

Block says … nothing.

They didn’t address this one in their rebuttal. I suspect it’s because they were laughing too hard.

Alex says … BaaS. You’re describing BaaS.

Hindenburg gives it a good shot here. They try their hardest to make this sound diabolical. They even suggest that Block may be facing an inquiry from the SEC over this practice (PayPal is already cooperating with an SEC investigation into its use of a Durbin-exempt issuing bank partner, although it’s unclear what, if anything, will come from that).

But come on, man. This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s just smart vendor procurement.

I’m not sure if Hindenburg Research knows what banking-as-a-service is, but this is absolutely just the way that this works … for everyone in fintech. No laws are being broken. Indeed, the spirit of the law (let’s ensure community banks can continue to make money from issuing debit cards) is being upheld … just not quite the way that the U.S. Senate might have imagined.

Amusingly, Hindenburg failed to bring up perhaps the most salient point in this argument – that Block has a bank charter (an industrial loan corporation charter from Utah), which should disqualify it from exploiting this loophole. This wouldn’t be a great argument (the charter is specifically for Block’s small business bank, Square Financial services), but you’d have liked to see them try it.

Hindenburg says … Block is overvalued.

Here’s the end of the Hindenburg report. It is savage:

Traditional bankers walk around in suits and ties, making them relatively easy to spot in the wild. This is a helpful feature for normal people who can then treat them with appropriate skepticism, knowing that bankers often work overtime to take advantage of people, avoid regulation, and extract money from the government.

By comparison, Jack Dorsey cloaks himself in tie-dye t-shirts and a guru beard, all while professing to care deeply about the demographics he is taking advantage of.

It has been an effective modern marketing approach—Dorsey has been celebrated by regular people, Silicon Valley elite, and investment bankers alike on his path to becoming a muti-billionaire.

But a close look at Block shows that it has not actually changed the game—like traditional financial services companies, its key focus seems to be on dressing up predatory loans and fees as revolutionary products, avoiding regulation and embracing worst-of-breed compliance policies in order to profit from its facilitation of fraud against consumers and the government.

The company seems to be betting that the consequences will either be a ‘cost of doing business’ or at the very least, come later.

Either way, we expect the luster will wear off and investors will realize that Block is really a money-losing, undifferentiated loan & fee originator. Like many of its peers in fintech and banking, it will eventually trade closer to its net tangible book value.

Block says … it’s not overvalued.

I mean, they don’t say this explicitly in their rebuttal. I can’t give you a quote here from Jack Dorsey or anything. But obviously, they manifestly disagree. That’s the game we’re playing here.

Alex says … hard to say.

Honestly, after the last couple of years, I don’t even know what value is anymore.

Is Block overvalued? THIS IS NOT INVESTING ADVICE, but here are some scattered thoughts:

- Hindenburg makes the case that its price is out of whack, “Block is valued like a profitable growth company at an EV/EBITDA multiple of 60x; a forward 2023 “adjusted” earnings multiple of 41x; and a price to tangible book ratio of 13.1x, all wildly out of line with fintech peers.”

- The fintech peers that Hindenburg compares Block to in the report include Affirm, Robinhood, SoFi, and Upstart. This seems really weird to me. Block is a big business. The report focuses on its consumer product (Cash App), but it also has a whole merchant services business (Square … which, as mentioned above, now includes a bank) and some crypto stuff that I don’t really understand. In theory, the combination of the consumer and merchant businesses (which are slowly being integrated) is more valuable than those pieces individually. I’m not sure how much of that ‘future value’ is currently priced into Block’s share price or how much should be priced in, but Hindenburg doesn’t even consider it.

- Block paid way too much for Afterpay. This is obvious now but was hard to see at the time (everything goes up and to the right!) Hindenburg dedicates a section of its report to Afterpay, but I found most of it unpersuasive. It was a bad deal, but investors knew what they were getting.

- That closing quote from Hindenburg was really negative about banks (tell us how you really feel!), which is ironic as it does seem like Block is headed down the road of becoming even more of a regulated financial services provider than it is today. I have no idea exactly what that will look like (Will Cash App eventually stop using partner banks? Will the company acquire a non-ILC charter?), but it’s amusing to imagine what Hindenburg would say about it.

Static Electricity

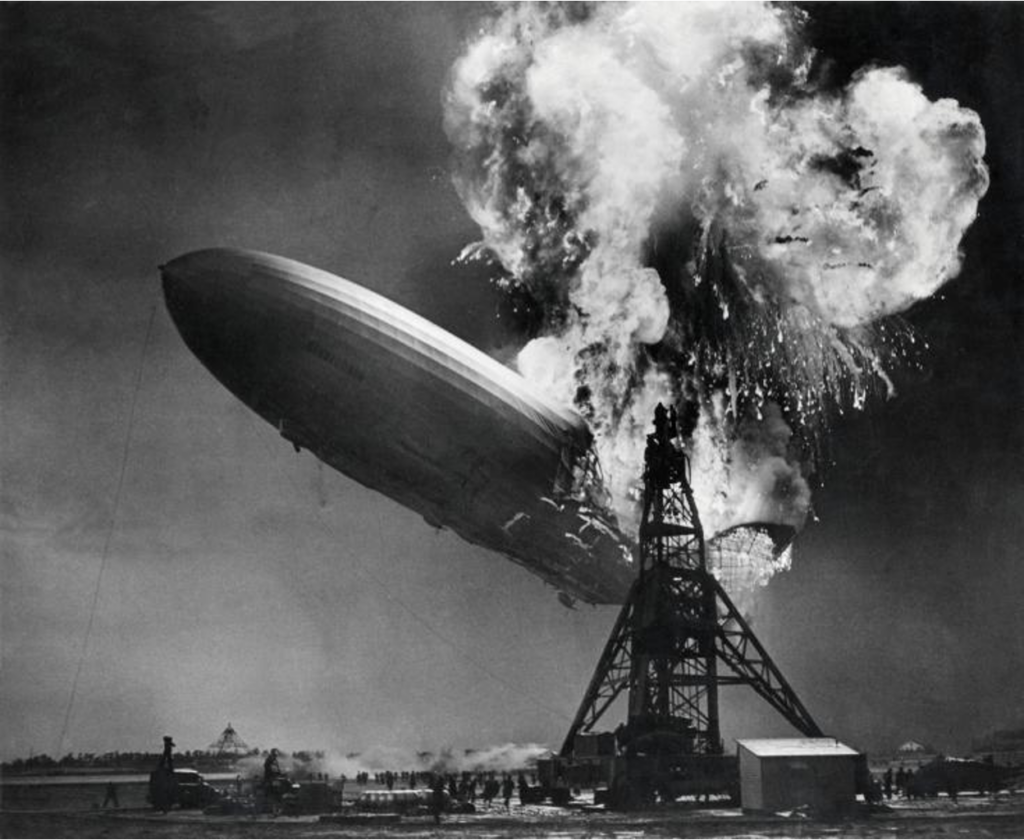

No one knows what caused the destruction of the Hindenburg on May 6, 1937.

One of the most popular and well-supported theories is static electricity.

While attempting to land, the Hindenburg descended through stormy conditions. These conditions increased the electrical charge of the ship (which was already highly charged relative to the ground). When the landing ropes were thrown down, the outer frame of the airship was instantly grounded, but the inner skin of the ship (which was separated from the frame by a small air gap) remained highly charged. This differential produced a spark that jumped across that gap and ignited the hydrogen.

Nothing nearly so dramatic will happen in the wake of this report, but I do hope that the differential between the Block Longs and Shorts will spark some interesting conversations about the future of fintech.