I’m confused by Apple Pay Later.

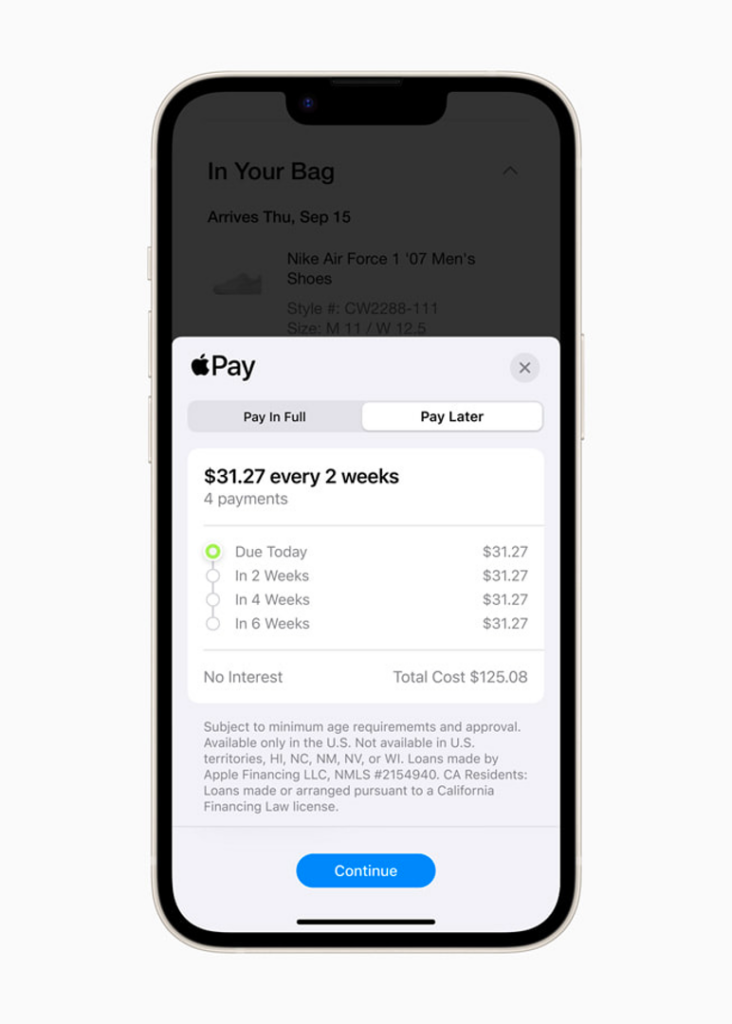

I know it’s a pay-in-4 buy now pay later (BNPL) product, similar to the ones that Klarna, Afterpay, and Affirm have been offering for a while. The consumer is given the option to split purchases between $50 and $1,000 into four equal installments, with the first installment being paid at checkout and the remaining three installments being repaid biweekly over a six-week span. There is no interest or fees, and all of the consumer’s Apple Pay Later loans can be tracked and managed in the Apple Wallet app.

It just seems like … Apple doesn’t really want its customers to use the service?

I know that sounds weird, given the work they’ve gone through to build it.

Indeed, Apple Pay Later is one of the first outputs of Apple’s ‘Breakout’ initiative, in which they are cutting out external partners and building a lot more of their financial services products in-house. Apple Pay Later is funded off of Apple’s own balance sheet, and Apple is originating the loans itself using state lending licenses that it has acquired.

But consider these additional facts:

- In order to be able to use Apple Pay Later, consumers must first go into Apple Wallet and apply for an Apple Pay Later loan. Consumers must specify the amount of money they would like to borrow, and, only after they are approved, are they able to choose Apple Pay Later as a payment option within the Apple Pay checkout flow. This is a significant departure from the standard (and much more convenient) design pattern in pay-in-4 BNPL, which embeds the loan underwriting process within the checkout experience.

- Apple, like most other pay-in-4 BNPL providers, will perform a soft credit check on consumers who apply for a loan. However, reading between the lines a bit, my educated guess is that Apple will be much more conservative in who it approves (and for how much) than most of the other pay-in-4 BNPL providers have been.

- Unlike its pay-in-4 BNPL competitors, Apple Pay Later isn’t integrated with specific merchants. Instead, it uses a digital Mastercard payment credential, issued by Goldman Sachs, to facilitate the transaction. The advantage of this approach is that Apple Pay Later will work anywhere that Mastercard is accepted. However, the downside is that individual merchants will have no incentive to push Apple Pay Later as a preferred payment method with their customers. Such ‘payment steering’ has proven very effective in driving adoption for other pay-in-4 BNPL providers.

Taken all together, these product choices paint a picture of a company that isn’t terribly serious about competing with Klarna, Afterpay, and Affirm.

Or maybe that’s unfair?

Maybe a more accurate way of saying it is that Apple has built a pay-in-4 BNPL product that actually makes sense and can stand on its own as a profitable, sustainable product.

Maybe everyone else in BNPL is crazy, and Apple is the sane one.

No Loss Leaders

I was surprised to learn recently (thanks to my brilliant Workweek colleague Trung Phan) that Costco never sells anything at a loss.

Jim Sinegal, Costco’s founder and former CEO, described it like this in a 2009 interview:

The only time we sell below cost is when we’ve made a mistake and have to mark it down. We don’t engage in loss leaders.

Loss leaders – products that are sold for less than their market cost in order to attract customers and sell them additional, high-margin products – are very common in retail. My assumption was that Costco, which sells rotisserie chickens for $4.99 and hot dog and soft drink combos for $1.50, probably had at least a few loss leaders.

But no. They refuse to embrace that strategy. Instead, they move heaven and earth to keep their prices low while still not taking a loss on any product. They are fanatical about it. According to the current CEO of Costco (Craig Jelinek), when he told Jim Sinegal that he wanted to raise the price of the hot dog combo meal, Sinegal replied, “If you raise the [price of the] f**ing hot dog, I will kill you. Figure it out.”

Here are some things Costco has figured out over the years to keep the price at $1.50:

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

- It dropped leading hot dog suppliers like Hebrew National and Nathan’s because they wouldn’t lower prices.

- In 2009, Costco built its own hot dog manufacturing plant in LA (and has a second one in Chicago).

- It got better pricing on buns, ketchup, and mustard.

- It removed onions and sauerkraut as free condiments.

- It dropped Polish sausages.

- The pop that came with the combo was swapped from a can to refillable fountain soda.

This is a little bit crazy (when Sinegal was asked what it would mean if the price of the hot dog combo ever went up, he replied, “That I’m dead”), but it’s my kind of crazy. Loss leaders can be effective in certain circumstances, but generally speaking, I think it’s a dangerous business strategy.

Especially in financial services.

Loss leaders in financial services are dangerous because a lot of what we do in this industry comes with asymmetric downside risk. When you’re lending money, for instance, the line between breakeven and catastrophically broke is a lot thinner than you might think.

And even when the financial product in question has relatively symmetrical risks and rewards, it’s still a dangerous idea to sell it at a loss or give it away for free because the market in which you’re selling it can move against you very quickly.

A good example of this is free checking, which most banks offered as a loss leader until the Durbin Amendment came in and capped debit interchange fees. This regulatory change spurred banks to introduce new monthly fees for debit cards, which consumers and elected officials completely freaked out about. This, in turn, caused banks to backtrack on these fees and instead ramp up penalties on overdrafts and non-sufficient funds (NSF) fees, which regulators and elected officials also freaked out about. This then led to most banks reducing or eliminating overdraft and NSF fees, while still being expected to offer at least one basic checking account product for free.

The moral of the story is that it’s perilous, in a highly regulated and carefully-watched industry, to give a product away for free or sell it at a loss, with the expectation of being able to make up the profits in other areas down the line.

Most banks that have been around for a while have learned to be careful with loss leaders.

ZIRP! ZIRP!

Fintech companies haven’t learned that same lesson.

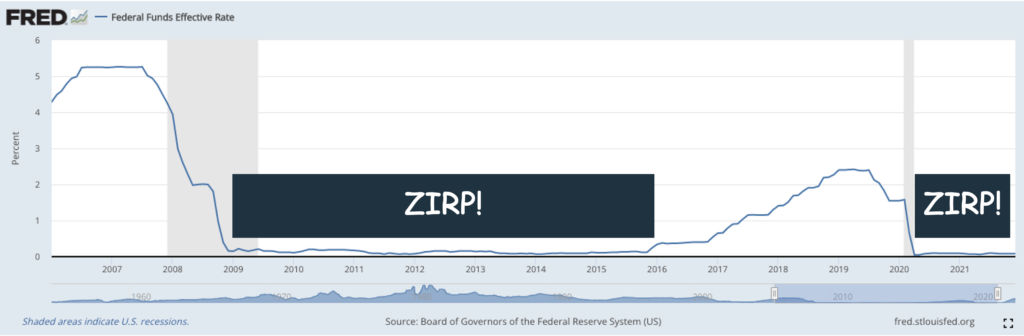

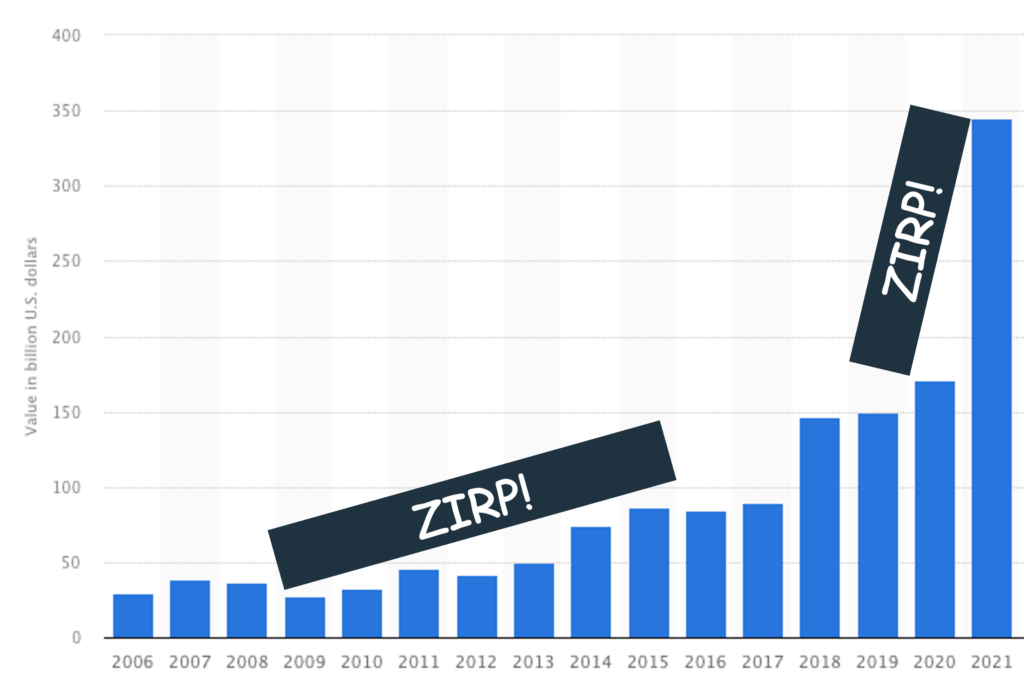

If this is the environment that banks learned to navigate:

Then this is the environment that fintech companies, post-2009, have been playing in:

And to stretch the analogy to its breaking point, the Super Star that gave fintech companies their invincibility was the prolonged use of zero interest-rate policy (ZIRP) by the Fed, between 2009 and 2016 and, again for a couple of years in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you compare the Federal Funds Effective Rate during those times:

To the amount of venture capital investment collected by private companies in the U.S.:

It’s easy to spot the pattern.

ZIRP! ZIRP!

Interest rates go to zero (or close to it), investors start getting desperate for yield, huge piles of money start getting dumped into places that aren’t accustomed to it, and stuff starts to get weird.

Weird how, you ask?

Well, every startup – from food delivery services to mattress manufacturers – starts referring to itself as a technology company in order to make itself maximally appealing to investors looking for high-yield, risk-on investment opportunities. These companies rake in absurd amounts of money and are instructed to acquire as many customers as possible as quickly as possible, regardless of the consequences. These companies design inefficient, money-losing business models that produce magical (but obviously untenable) customer experiences. They launch these experiences and iterate on them at a rapid pace, with little-to-no regard for regulatory compliance. And they spend every remaining dime in their checking accounts on marketing and customer acquisition; everything from digital advertising to Superbowl commercials.

Every industry saw some version of this phenomenon play itself out over the last 10+ years, but fintech was one of the most prominent examples. During the ZIRP years (particularly the COVID-era ZIRP years), fintech companies benefited disproportionately from the yield-hungry influx of money into VC. To give just one example (which I will be repeating endlessly until I die) – in 2021, one out of every five dollars invested in a private company globally went to a fintech company.

This surge in investment resulted in a large number of deeply appealing and unsustainable products, but I think the best example, the one that will come to epitomize this era of fintech, is pay-in-4 BNPL.

Pay-in-4: Fintech’s Loss Leader

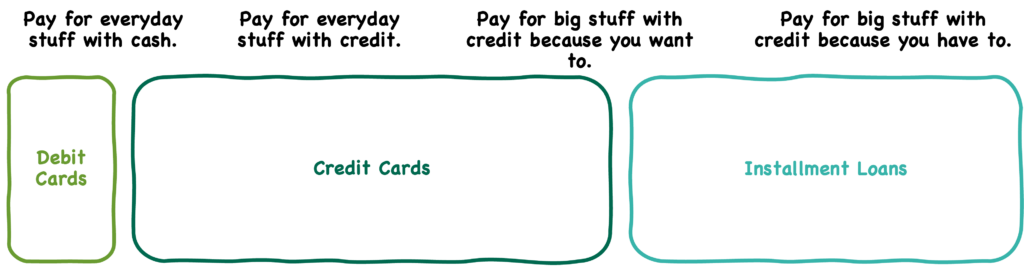

I think the best way to understand how unusual pay-in-4 BNPL loans are, as a standalone product, is to put them in the context of the consumer lending and payment products they have been attempting to disrupt.

If you think about the types of payments needs that consumers have, in very simple terms, it breaks down like this:

- Pay for everyday stuff with cash. This is the stuff – groceries, fuel, utilities, kids’ books (at least in my house) – that we buy on a regular basis with the money that we earn from our jobs.

- Pay for everyday stuff with credit. Same stuff, but we occasionally have to buy it on credit because of cash flow shortfalls. These shortfalls are more common, obviously, for consumers that have lower incomes, and they are exacerbated by personal decisions (spending more money than you have) and macroeconomic conditions (inflation).

- Pay for big stuff with credit because you want to. These are bigger items that we buy less frequently – televisions, exercise bikes, couches, a new garage door because you stupidly backed up into yours without looking first (again, that last one is me). We could, technically, buy these with the cash we have on hand, but it often makes more sense to buy them on credit and spare ourselves the cash flow crunch (especially if the merchant selling them is offering 0% interest financing).

- Pay for big stuff with credit because you have to. This is a combination of the big-ticket items mentioned above, which some of us might want/need but not be able to pay for out of our own pockets, as well as bigger-ticket items – solar panels, cars, houses – that most of us can’t afford without credit.

Over time, banks have developed lending and payment products to address this continuum of payments needs:

- Debit Cards. Provide a convenient way to pay for everyday stuff with the cash that is in the consumer’s bank account. As mentioned above, debit cards are generally free or very low cost to consumers, and it’s easy for consumers to get access to them.

- Installment Loans. Provide lump-sum financing for big stuff that is purchased infrequently. Installment loans allow for the purchase of really expensive stuff (cars, houses, etc.) that most consumers wouldn’t be able to afford upfront on their own. They are also used as a cash flow management tool by consumers that could afford to buy the item in question but choose the spread the payments out over time instead. Installment loans usually charge a combination of fees and interest on the principal (although merchants and manufacturers will sometimes subsidize these costs), and they are typically only available to consumers with near-prime credit scores or better.

- Credit Cards. A hybrid product that covers a wide swath of the middle of this payments needs continuum. They are used to finance the purchase of big-ticket items that a consumer could have also used cash to buy. They are used to finance purchases – both big and small – that consumers couldn’t have bought on their own. And they are used by some consumers in the same fashion as a debit card, to pay for everyday stuff with the money that they already have. Depending on how they are used, credit cards can be free or very low cost (if the consumer pays off their full balance every month) or very expensive (if the consumer carries a balance over to the next month and pays interest and if they incur penalties such as late fees). Consumers typically must have at least near-prime credit scores to get them, although there are some cards designed for sub-prime and credit-invisible consumers.

We should pause here for a second and talk about how brilliant credit cards are as a standalone product.

(Editor’s note – this is not an argument about the morality of credit cards, which many folks [including myself] have strong feelings about. I wrote admiringly about the Costco hot dogs earlier in this essay. That doesn’t mean I agree with Jim Sinegal’s claim that “they’re very healthy; they’re very good for you.”)

Credit cards work because the different groups of consumers that use them act as cross-subsidizers and risk hedges for each other. To oversimplify a bit – ‘transactors’ (those who pay their full bill every month) generate predictable, but relatively low revenue streams at a low risk. They are generally using credit cards as a combination of a debit card and a 0% interest lending facility for larger purchases. By contrast, ‘revolvers’ (those who carry a balance month-to-month) generate higher revenue streams (interchange + interest and the occasional late fee), but it is less predictable and has higher risk. They are using credit cards as rolling loans. Every credit card issuer has a slightly different strategy, in terms of the mix of customers that they target and the product levers they use to attract and incentivize behavior, but it’s all built on this mix of transactors and revolvers.

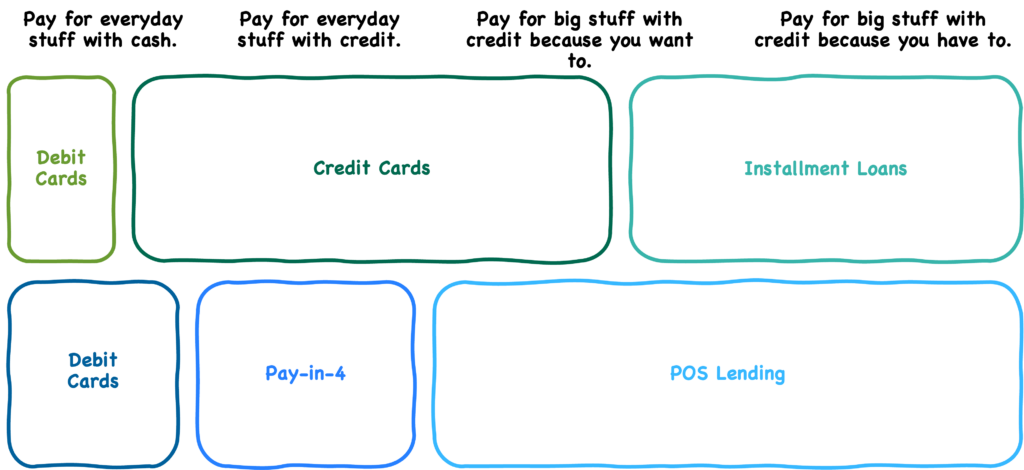

What’s interesting about BNPL is that it’s advancing a very different vision for how to support consumers’ continuum of payments needs.

- POS Lending. Covers all of the big stuff that consumers might want or need credit for and is underwritten and priced similarly to traditional bank installment loans. The key difference is in distribution. Rather than requiring a consumer to come to you for the loan (as banks have traditionally done), BNPL providers that offer POS loans are embedding their products within the point of sale. Most of the penetration of BNPL within this area has come at the lower end of the transaction range (couches, exercise bikes, etc.) because there has been less competition and more digitization in these areas, but the basic principle is applicable to the top end of the range as well (i.e. embedded finance for cars, houses, etc.) Major BNPL players in this space include Affirm and Green Sky (acquired by Goldman Sachs).

- Pay-in-4. Covers the “pay for everyday stuff with credit” category, usually between $50 and $1,000, although a majority of the volume is for transactions less than $250. Much of the transaction volume comes from higher-margin, discretionary-spend categories like apparel, footwear, fitness, accessories, and beauty, although a growing amount of volume is coming from less discretionary categories like groceries and fuel. Pay-in-4 products are unambiguously less expensive for the ‘revolver’ customer archetype than credit cards, as they charge neither interest nor (for the most part) late fees. They are also much more accessible to consumers, including those without traditional credit histories. Providers of pay-in-4 BNPL loans make money by charging the merchant a percentage of the overall transaction (typically, 3%-6%, which is higher than credit card interchange rates). Major BNPL providers in this space include Klarna, Afterpay (acquired by Block), and Affirm.

- Debit Cards. Covers the “pay for everyday stuff with cash” category. Affirm expanded into this area with the launch of a hybrid debit card/pay-in-4 product, which gives customers the flexibility to split eligible purchases up into installments or to simply pay for them with cash from their bank accounts. Klarna offers something kinda similar (except all purchases are split into 4 payments), and one could imagine Block (which already offers the Cash App debit card) launching something similar with Afterpay.

With pay-in-4, BNPL providers have unbundled the credit card and created their own loss leader.

Pay-in-4, like any good loss leader, is really appealing. I remember Matt Burton (a partner at QED Investors) saying on a panel that the easiest thing in the world is to give away free money. And he’s right. And pay-in-4 BNPL loans have, over the last couple of years, been the closest thing in the market to free money for consumers. No interest rate. No fees (for the most part). No need for a prime or near-prime credit score. No need to worry about your credit score getting dinged up if you’re late for a payment. No need to worry about being declined because you’ve stacked up a dozen different loans from other BNPL providers.

And it has been great for merchants too! Pay-in-4 has helped them move a massive amount of merchandise ($100 billion in 2021, according to Cornerstone Advisors), much of that incremental to what they would have ordinarily sold (Shopify, which partnered with Affirm to offer BNPL, claims that merchants see a 50% increase in average order value). This is the unrealized spending that that merchants have always wanted to unlock with their customers, they just didn’t have lending partners willing to underwrite the risk … until pay-in-4 BNPL came along.

Of course, there’s a good reason for that. A lot of the spending volume unlocked by pay-in-4 is deeply risky.

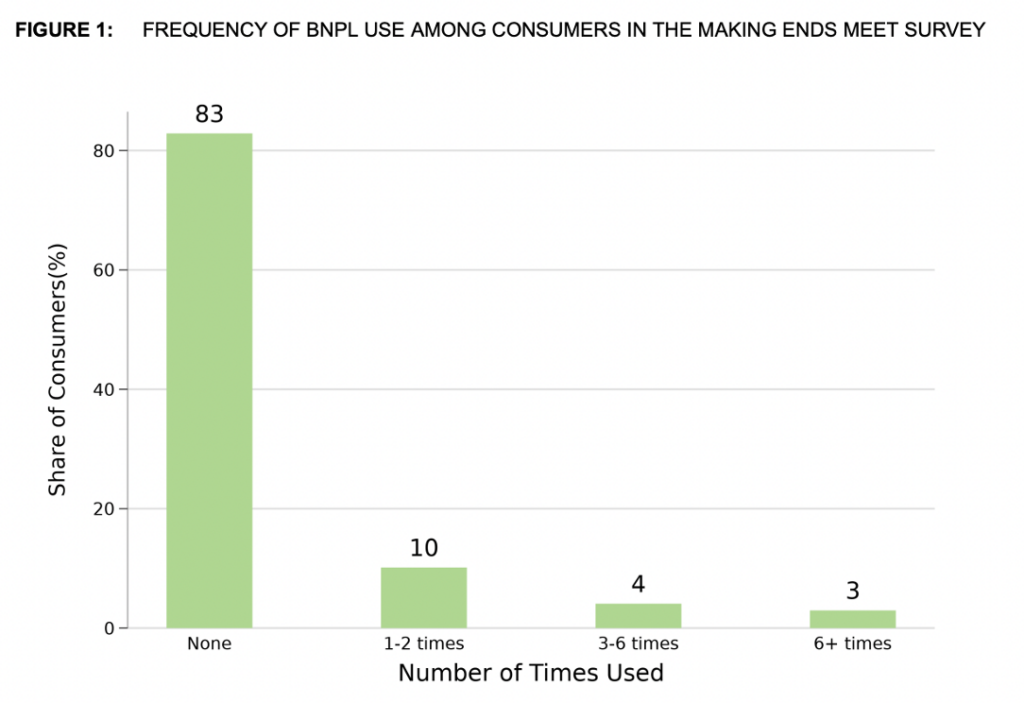

According to a recent survey conducted by the CFPB, which is representative of the adult U.S. population with a credit report (the 11% of credit invisible consumers in the U.S. was not captured), most pay-in-4 BNPL volume is concentrated among a small set of heavy repeat users.

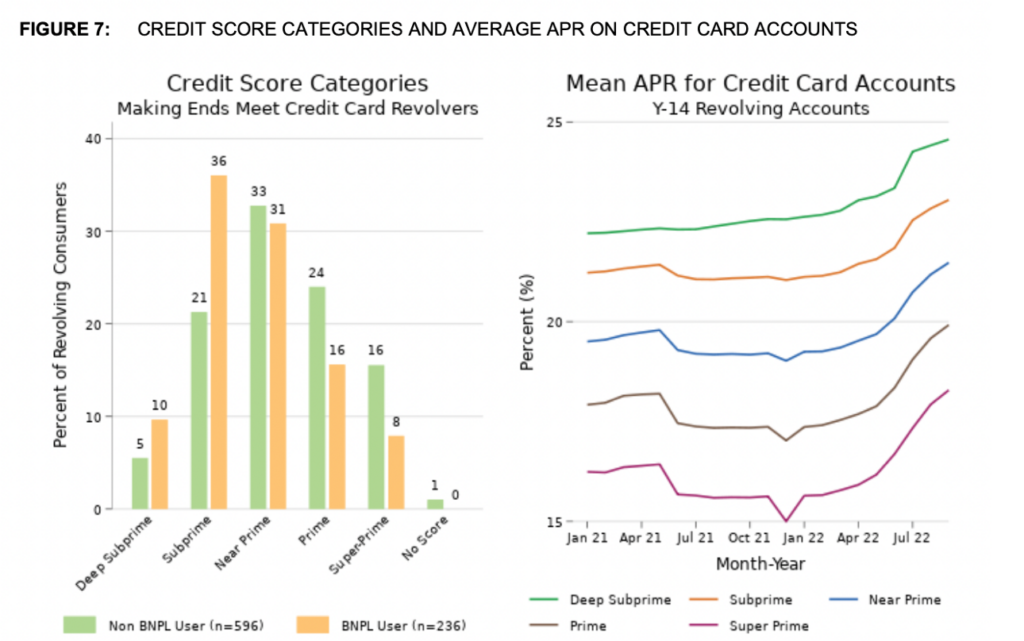

These users are more likely than non-BNPL users to be sub-prime, to have credit cards, to revolve debt on their credit cards, and to have higher interest rates on their credit cards.

In other words, pay-in-4 BNPL providers carved out the riskiest and most profitable segment of credit card users, capped their ability to monetize them (by not charging interest), and left out the low-risk users that could have balanced out their portfolios.

(Editor’s note – it’s not like BNPL providers didn’t want to attract the lower-risk credit card ‘transactors’; it’s just that pay-in-4 provides very little utility to those consumers. As a replacement for making everyday purchases, it’s more complicated to manage a dozen installment loans than one card account balance. And for purchases on the larger end of the $50 – $1,000 spectrum, these users really value their credit card rewards.)

Building an entire industry around this product shouldn’t have been possible. The business model just doesn’t make sense.

Except … ZIRP! ZIRP!

In a zero-rate environment, a number of flaws with this business model were (temporarily) removed:

- Credit risk. Stimulus checks and other government interventions during the early days of the pandemic kept delinquency rates on consumer lending products exceptionally low in 2020 and 2021. This was a boon for credit card issuers, but it was absolutely essential for BNPL providers who are structurally unable to generate revenue from missed payments.

- Funding costs. Lending 101 – the money that you make comes from the difference between what you charge customers (the merchants, in the case of BNPL) and what you have to pay for the money that you are lending out. Given BNPL providers’ inability to reprice their loans in response to rising funding costs (they can’t just automatically jack up their merchants’ fees), operating in a predictably low-rate environment (where borrowing is cheap and secondary market investors are eager to buy your loans) is essential.

- Customer inertia. If you want to get consumers to, en masse, change the way they pay for an entire category of goods and services, you’re going to need a lot of money. Money for advertising. Money for merchant incentives. Money for lobbying. As we already covered, ZIRP brought a lot of money into fintech, and BNPL providers were massive beneficiaries of this influx. Between 2019 and 2022, Klarna raised nearly $4 billion in outside investment.

Now those flaws are being exposed, as the Wall Street Journal recently noted in regard to Affirm, which has seen its share price slip dramatically over the past year:

Affirm is trying to adjust to a world of higher interest rates. It just isn’t doing so fast enough.

Buy now, pay later providers boomed during the zero-interest years by offering zero-percent financing to shoppers. But with the Federal Reserve aggressively raising rates, the days of free money are rapidly coming to an end.

Pay-in-4 BNPL Was Never a Product

One of the challenges with ZIRP, perhaps the most foundational challenge, is being able to tell what’s real.

Is that guy over there just insanely good at Super Mario? Should I adjust my strategy and stop being so cautious? It seems to be working great for him.

After a while, you start to doubt yourself.

I am as guilty of this as anyone. During the BNPL boom years, I thought it was absolutely insane that the big credit card issuers weren’t taking the competitive threat posed by BNPL more seriously. Last year, American Express’ CEO Stephen Squeri said:

Buy now, pay later is not really a competitive threat to us. It’s targeted at debit card issuers. As a customer acquisition vehicle it’s not the game we’re playing.

I thought this was asinine at the time; the last groans of a dinosaur before it went extinct.

I’m an idiot.

“As a customer acquisition vehicle it’s not the game we’re playing.”

Squeri had it exactly right. I was thinking of pay-in-4 BNPL as a product, but it’s not. Loss leaders aren’t products, they’re customer acquisition strategies.

Pay-in-4 BNPL was a customer acquisition hack enabled by ZIRP. It wasn’t a product that you could build a sustainable business around.

Interestingly, this is exactly how Klarna has started talking about it:

“Candidly, ‘buy now, pay later’ is just a feature,” David Sykes, Klarna’s chief commercial officer, told DealBook. “If all you’re doing is offering the ability to break a purchase up into installments, we don’t think, long term, that’s dynamic enough.”

For Klarna, pay-in-4 was the foundation on which to build a fully-featured commerce enablement platform for merchants (a common Klarna talking point these days is that they spend more time talking to the marketing folks at merchants than the payments folks).

For Affirm, pay-in-4 was an on-ramp to get more customers into its ecosystem and cross-sell higher-margin products (a positive development that Affirm has been emphasizing in its earnings calls lately is the growing percentage of repeat customers).

For Block, the acquisition of Afterpay and its ample pay-in-4 business was an important (and expensive) step to bridge its Cash App and merchant services ecosystems (this article does a good job explaining the strategic thinking behind the acquisition).

For me, pay-in-4 was a very useful lesson in the perils of loss leaders in financial services and the reality-warping powers of ZIRP.

Ohh, and for Apple, launching Apple Pay Later in a rising rate environment and in a market saturated by irrational-but-compelling competitors, pay-in-4 will likely be a disappointment.