The first piece of fintech content that I ever wrote was a white paper – Operational Excellence: The Prescreen Revolution.

I was working as an intern in the marketing department at Zoot Enterprises, which is a fintech infrastructure company specializing in automated credit decisioning. It was my first job, of any kind, and I didn’t know my ass from my elbow. My boss was a traditionalist on the subject of white papers. The first meeting that we had about it started with him giving me an overview of the history and etymology of the term ‘white paper’ (it dates back to a document that was drafted at the request of Winston Churchill in 1922) and assuring me that all corporate white papers had to adhere to a set of strict, academic requirements in regards to research and composition.

Given all of this, it won’t surprise you to learn that it took me about nine months to get my 12-page white paper approved and published, with lots of red ink and exasperated sighs along the way.

It was a formative experience, and as such, I’ve maintained an ongoing interest in the topic of the paper ever since.

That interest recently flared when I was thinking about a few different trends in the consumer lending space, so I thought it would be worthwhile to dust off my old notes and write a bit more about prescreen.

I promise I’ll keep it under 12 pages this time!

What is prescreen?

Prescreen is the proactive evaluation of a consumer’s creditworthiness for the purpose of offering them a credit product or enticing them to apply for one.

You’ve almost assuredly encountered prescreen in your day-to-day life.

When a bank or fintech company invites you to discover if you’re pre-approved for their credit product with no impact on your credit score? That’s prescreen. If you’re above a certain age, you might remember receiving pre-approved offers for credit cards in your mailbox. That was prescreen too.

As with most things in financial services, prescreen is a highly regulated activity. I’m not a lawyer, and nothing in this newsletter should ever be considered legal advice, but here are the basics of how it works in the U.S.:

- The Fair Credit Report Act (FCRA) is the relevant law here. The FCRA regulates the collection, dissemination, and use of consumer information, including consumer credit information. According to the FCRA, companies are only permitted to obtain a copy of a consumer’s credit report for a permissible purpose (lending, insurance underwriting, employment screening, etc.) and only after receiving that consumer’s explicit permission as a part of that consumer-initiated request. (Editor’s Note – for the remainder of this explainer, I’m not going to talk about insurance because it’s not really my bag, but just know that generally, the same rules apply to both credit and insurance.)

- The one exception to this requirement for consumer-initiated permission is prescreen. According to the FCRA, consumer reporting agencies (like the big three credit bureaus) may furnish a consumer’s credit report for the purpose of credit underwriting without the consumer’s permission as long as the following things are true: A.) the consumer is at least 21 years old, B.) the consumer hasn’t opted out of receiving prescreened offers, and, C.) a firm offer of credit is made to the consumer if they meet the company’s eligibility criteria.

- The credit bureaus (and other consumer reporting agencies) keep a record of all of the times that a consumer’s credit report has recently been furnished to a third party. These are known as inquiries. Inquiries are classified as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ depending on the purpose for which the report was requested. Hard inquiries are when a consumer explicitly applies for credit. Soft inquiries are everything else (employment, consumer self-monitoring, etc.) Having too many hard inquiries can lower a consumer’s credit score because it can be seen by the lender as an indication that the consumer is desperate for credit. The key thing to know, for the purpose of today’s essay, is that prescreen transactions don’t count as hard inquiries, hence the promise from banks and fintech lenders – “with no impact on your credit score”.

The consumer reporting agencies are the regulated entities under the FCRA, and thus they set the rules for how their data can be used in the credit granting process (including in prescreen), based on their interpretation of the law and their commercial objectives. As you might imagine, those rules are somewhat fluid and prone to change over time (all while staying within the general bounds of the limited guidance provided by the FCRA).

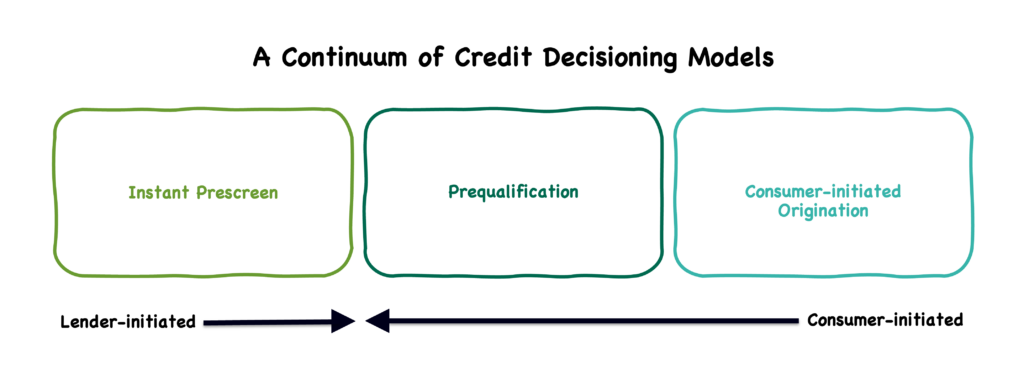

Think of it like a continuum. On the one end, you have consumer-initiated requests for credit, and on the other end, lender-initiated prescreen.

Across that continuum, I think there are three specific models, all of them well-suited to the current digital-first lending ecosystem, that are worth discussing in a bit more detail.

- Consumer-initiated Origination. This is what happens when you apply for a credit product. You fill out an application, which includes the personally identifiable information (PII) needed to match you up with your file at the credit bureaus (name, address, social security number, date of birth). As a part of that application process, you agree to allow the lender to pull a copy of your credit report. The lender does so and runs your entire report (and additional data that they have or acquire on you) through their credit decisioning process in order to arrive at a decision about whether to approve you for the product or not (and, if approved, determine the offer terms and pricing). Regardless of whether you are approved or not and whether you accept the lender’s offer or not, a hard inquiry is recorded in your credit report.

- Instant Prescreen. A lender wants to present a fully pre-approved credit product offer to an individual customer or prospect that hasn’t applied, so they send the consumer’s PII to the credit bureau (or an agent of the credit bureau). Because the lender has not received permission from the consumer to pull their credit report, the lender can’t see any of the data. Instead, the bureau (or its agent) evaluates the data from the credit report using the lender’s credit decisioning criteria and processes on the lender’s behalf. If the consumer is approved, the bureau passes the offer along to the lender for presentment to the consumer (the lender is required under FCRA to make a “firm offer of credit” to all those who qualify), and a soft inquiry is recorded in the consumer’s credit report (a hard inquiry is added if the consumer accepts the offer). If they aren’t approved, the lender is simply informed, “process complete,” and no additional data is shared, and no inquiry (soft or hard) is recorded. All of this happens in real time during the interaction with the consumer.

- Prequalification. This model is a bit of a blend of the first two. In it, a lender presents a customer or prospect with the option to see if they qualify for a credit product. If the consumer decides to find out, they provide a few pieces of personal information (name, address, and maybe their date of birth). The lender then uses that information to pull the consumer’s credit report, feed the data into their credit decisioning process, and determine which credit product (or products) the consumer is pre-approved for. A soft inquiry is recorded in their report, and they are presented with the option to officially apply for the product(s) through a streamlined account opening process. If the consumer opts to apply, a hard inquiry is recorded in their report.

The popularity of each of these models (and the many others that we could map against this continuum) wax and wane as the industry evolves and the credit bureaus’ strategic priorities shift. For example, as batch prescreen (a slightly different model which was used to generate those pre-approved offers in the mail) has fallen out of favor in the last 10 years, the credit bureaus have focused on driving the adoption of the prequalification model. By contrast, instant prescreen has been deemphasized by the credit bureaus during that span, and is, today, not widely known or understood in the industry, even though it is a model that many big bank lenders use (and have been using for years).

The important question, though, is what comes next? How might the continued evolution of the consumer lending industry impact prescreen, customer acquisition, and the credit granting process?

Where does prescreen fit in the future of consumer lending?

My basic theory is that there are two divergent directions that consumer lending is evolving.

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

The first is embedded lending.

I’ve written a lot about embedded lending in the newsletter, so I won’t rehash too much of that here, except to say that the core point of embedded lending is convenience. By making a credit product easily accessible to a consumer in the context of the transaction that the consumer needs the credit product for, embedded lenders dramatically reduce the time and work necessary for the consumer to get what they ultimately want.

The trade-off with embedded lending is certainty. If you accept whatever credit product is presented at the point of interaction, you are, by definition, not shopping around for the best deal. You don’t know if the price and terms of the offer are the best that you could possibly qualify for.

And that brings us to the second direction that consumer lending is evolving – competitive lending.

Now, obviously, it’s not a novel or useful observation to point out that consumer lenders compete with each other for customers. We all know that. It’s been true for thousands of years.

However, in the modern fintech era, there has been a strong focus on enabling consumers to reduce information asymmetry (the gap between what the consumer knows about lenders’ perception of their creditworthiness and what lenders actually perceive about the consumer’s creditworthiness), and force lenders to compete more fiercely with each other to earn the consumers’ business.

Credit Karma is a good example. Its initial value proposition was simple – we’ll give consumers their credit scores (for free) and help them shop for the best credit products that they would be likely to be qualified for (which we will monetize through referral fees from lenders). The whole concept is built around empowering consumers to understand and improve their creditworthiness (in the eyes of lenders) in order to acquire the best possible credit products at the best possible prices.

It’s essentially the opposite of embedded lending. It’s certainty over convenience.

Now, to be clear, these two different visions for the future of consumer lending can, and indeed do, coexist. They’re not mutually exclusive. There are likely some credit products that will always be better off being embedded. And other products where the benefits of transparency and intense competition will be of paramount importance. And, of course, broader shifts in technology and regulation will act as headwinds or tailwinds for each (e.g. software eating the world has been a boon for embedded lending, and open banking is likely to be an accelerant for competitive lending.)

However, what we should want, as an industry, is for each vision to evolve into its optimal form, the state in which consumers receive the maximum benefit.

And this is where prescreen can help!

The problem with most embedded consumer lending products is that they aren’t as convenient to acquire as they could be. Sure, they’re convenient (that’s the whole point!), but not optimally so. Most still require the consumer to fill out an application and get approved. That’s silly! Why do I have to go into the Apple Wallet (which is a mess) and fill out an application in order to get access to Apple Pay Later (Apple’s pay-in-4 BNPL product)? Apple knows everything about me. They have everything they need to confirm my identity and trigger an instant prescreen decisioning process in the background, without requiring any work from me. If I pass Apple’s instant prescreen decisioning process and am approved for Apple Pay Later, Apple could present that offer to me, in real-time, while I’m preparing to use Apple Pay to make a purchase, rather than requiring me to slog, proactively, through the Apple Wallet. And if I am not approved? I never know, and there’s no reason for me to be upset!

If I was a fintech founder building a BaaS middleware platform or some other type of infrastructure to enable embedded finance, I would absolutely have instant prescreen towards the top of my product roadmap.

(Editor’s note – If you are interested in learning more about the mechanics of instant prescreen and how it can be applied to a specific use case, let me know, and I will introduce you to the real experts on the subject.)

The problem with competitive lending is that it is becoming increasingly difficult to help consumers gain an accurate and holistic understanding of how a lender might view their creditworthiness and overall financial reputation. The consumer lending ecosystem is just too fractured for someone’s FICO Score to provide a clear reflection of their complete financial history. Thus, prequalification, as a tool for giving consumers certainty when navigating the financial services ecosystem, is increasingly less useful.

As Kevin Moss and I wrote about a while back, fintech is breaking the credit bureaus. You have fintech companies hacking into consumers’ credit reports using novel credit builder products. You have lenders responding to this trend by excluding those specific tradelines from their credit decisioning processes. You have fintech companies not furnishing their customers’ repayment data to the bureaus at all. You have open banking and cash flow underwriting. You have payroll data and payroll-linked lending. You have alternative repayment history data (rent, utilities, telco, payday. etc.) You have FICO, trying to update its scoring model to better reflect what’s actually going on in the market, but unable to convince lenders to upgrade (FICO 8 … still going strong!) And you have credit score monitoring providers like Credit Karma, trying to help consumers understand where they fit into all of this, but not even offering them their FICO Scores, much to the consumers’ confusion and frustration.

If I was a fintech founder focused on building the next Credit Karma, I would start from the assumption that there is no longer one number that can serve as the foundation to educate consumers on how they can establish, grow, and protect their financial reputation. Instead, I would build a service that allowed consumers to aggregate together all of the disparate pieces of information that can potentially be used to paint a picture of their financial reputation (traditional and alternative repayment data, banking data, payroll data, etc.) I would give consumers an unbiased, analytically-derived estimation of what that aggregated data might indicate to a lender about their creditworthiness. And based on that insight, I would attempt to steer them, without bias, to the lenders that would be most likely to meet their needs at the best price. And if I was successful in gaining sufficient consumer adoption, I would leverage that to create a modern, consumer-centric prequalification engine for bank and fintech lenders to plug into.

Evolution Not Revolution

I got it wrong in my white paper back in 2008.

Prescreen isn’t a revolution. It’s an evolutionary force multiplier.

And I hope that the next generation of builders in the consumer lending space capitalizes on it.