Banks are pretty good at finding and solving banking problems that look like banking problems.

There’s obviously still room to innovate and improve things on the margins, but, by and large, there aren’t a lot of true greenfield opportunities in financial services. Banks have already identified them all.

Unless they don’t look like banking problems.

This is what I find most exciting about embedded finance.

If we can distill financial services down to a set of genericized components and capabilities – tools in a toolbox – and we can put that toolbox into the hands of non-bankers, we can find and solve unsolved banking problems that have been hiding in plain sight.

Let me give you an example.

Let’s Say You Want to Build a Building

You’re Amazon, and you want to build a new office building.

How do you go about getting that done?

Well, first, you’re going to do a bunch of stuff that isn’t important for the story I’m trying to tell in this essay – picking out a location, acquiring real estate, designing the building and getting approvals, etc. – so let’s skip forward a bit.

OK, now you’re ready to actually build the building.

What do you do?

Well, you probably are going to line up financing from a bank. Typical debt financing usually covers about 70% of the total construction cost, with the remaining 30% being provided by the owner or other investors.

Next, you are going to hire a general contractor to manage the project.

(Editor’s note – big companies that build lots of buildings, like Amazon, usually have their own general contractors on staff, but for the purposes of this example, let’s pretend they hire an external GC.)

Then that general contractor is going to hire a raft of specialty subcontractors (electrical, plumbing, concrete, painting, etc.) to do the actual work. Those subcontractors will hire laborers, acquire the necessary materials, and start building the building under the direction of the general contractor.

Alright, next question – how does everyone involved in the construction of your new building get paid?

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Let’s start at the ground floor, and work our way up to the penthouse.

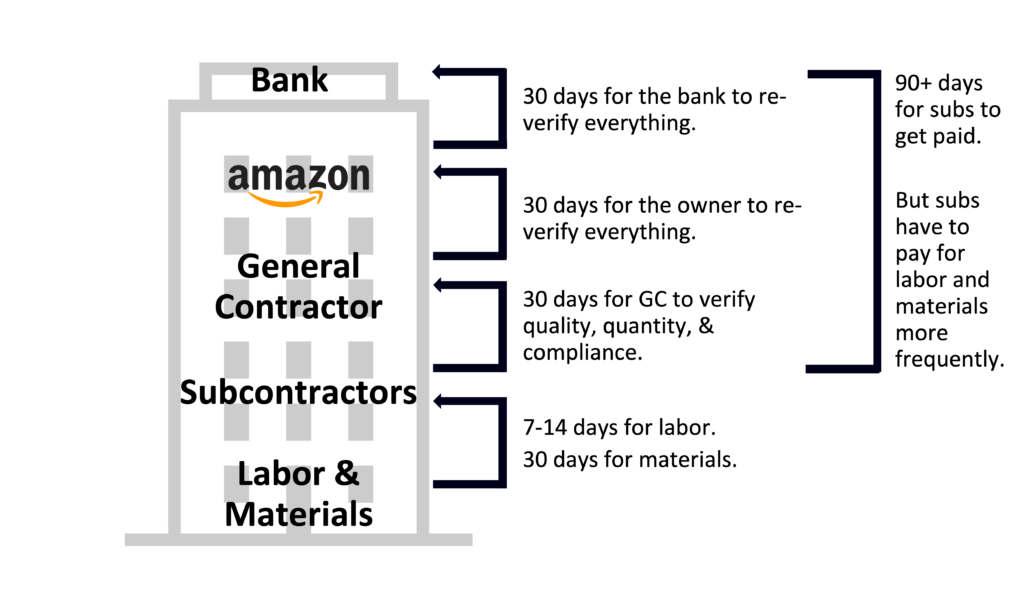

The laborers get paid by the subcontractors on a two-week or even one-week basis. The reason for this is simple (and obvious if you’ve tried to get a remodel done in the last 10 years) – competition for skilled construction labor is intense, and if a subcontractor doesn’t pay their laborers on a frequent basis, they lose the laborers.

Materials need to be purchased upfront by the subcontractors (you can’t build without building materials), and the standard payment term is usually 30 days (with a 2-3% premium for those terms built into the final price).

Subcontractors are usually paid in what are called progress payments. At the end of every month, a subcontractor will submit an invoice to the general contractor. The amount of that invoice will be for whatever percentage of the project was completed during that month. So, if the total cost of the project for a subcontractor is $500,000 and they complete 10% of the project during that month, the invoice for that month will be $50,000. Additionally, the owner will often retain a portion of the total amount (usually 10%) until the project is complete, in order to ensure that the subcontractors have satisfied all of their contractual obligations.

All of these invoices from subcontractors are aggregated together by the general contractor, who then submits a master payout request to the owner. The owner will then, in turn, submit a draw request from the bank that is financing the project.

Once the bank cuts the big check, the money flows back down to the owner and then to the general contractor, and then to the subcontractors.

Simple enough, right?

Last question (and this one is trickier) – who finances this construction project?

The obvious answer is the bank.

And, in one sense, that’s true. They are putting up a majority of the capital to finance the construction of the building, in exchange for a fixed interest rate, paid by the owner.

The bank is financing the building.

But who is financing the work to build the building?

To answer that question, we need to take a super quick detour and talk about mechanic’s liens.

What are Mechanic’s Liens?

In the U.S., generally speaking, anyone who supplies labor or materials for the improvement of real estate has a legal claim against that real estate for the purpose of recouping the costs of their labor or materials.

This is called a mechanic’s lien. It was originally dreamed up by Thomas Jefferson as a way to encourage construction in the newly created capital city of Washington, D.C.

Mechanic’s liens exist to ensure that contractors, builders, and suppliers don’t get stiffed by real estate owners.

They are an incredibly powerful tool.

In most states, everyone who works on a construction project or supplies materials for it is entitled to a mechanic’s lien, regardless of whether they have a direct contractual relationship with the real estate owner or the general contractor. This applies to subcontractors and any subcontractors that they hire, laborers, and material suppliers, among many others.

As you might expect, mechanic’s liens make real estate owners very nervous.

Imagine receiving an invoice from your general contractor and paying it (assuming that they paid all of their subcontractors and that the subcontractors all paid their subcontractors, laborers, and suppliers), only to discover that was not true, and now some of those subs and their subs and laborers and suppliers are suing you.

You end up paying for the work twice, which, obviously, you want to avoid.

And this brings us back to our question – who finances the work to build a building?

Trust, But Verify

In order to ensure that they are not paying for work that hasn’t been done yet or liable for subcontractors not paying their subs, laborers, or suppliers, real estate owners require a great deal of diligence to be done before they agree to make payments.

Typically, this starts with the general contractor. When the GC receives an invoice from a subcontractor, that GC will verify that A.) the subcontractor has done the quantity of work that they are claiming, B.) the subcontractor has done that work to the quality level that they committed to, and C.) the subcontractor has been in compliance with all of the requirements of their contract, including and especially the requirement to secure mechanic’s lien waivers from all the subcontractors, laborers, and suppliers that the subcontractor is working with. These waivers eliminate the risk for the owner that a subcontractor, laborer, or supplier might later claim that they weren’t paid for their contributions.

After the general contractor completes all this due diligence, a process that typically takes 30 days, and submits a request for payment to the owner, guess what happens?

The owner will conduct their own due diligence process – essentially rechecking the same things that the GC checked – before asking the bank for payment. And then, guess what happens?

Yep! The bank does the due diligence again!

Fun fact! Historians think it’s possible that when Russian history scholar Suzanne Massie taught Ronald Reagan the Russian proverb “trust, but verify”, she was actually giving him home renovation advice.

Regardless, the impact of all of these lengthy due diligence processes is that the subcontractors, who are required to pay for materials and labor upfront in order to do their work, end up floating those expenses while the general contractor, real estate owner, and bank verify the necessary information to remit payment, a delay that is routinely 90+ days.

Who finances the work to build a building?

The subcontractors.

And that’s neither optimal nor fair. Subcontractors are, in many cases, small business owners who are living fairly close to the edge. They don’t have excessive amounts of capital sitting around. Their cash flow is lumpy and unpredictable (they usually don’t have the capacity to do multiple big projects at the same time). They, like a lot of small business owners, don’t always have pristine personal credit scores.

So how do subcontractors finance their projects? How do they even get enough confidence in their finances to bid on big projects?

There’s no good answer.

Banks don’t know how to safely lend to subcontractors based on the project work they have taken on. So, instead, subcontractors spackle over holes in their balance sheets with whatever they can find – unsecured personal loans, credit cards, and even home equity loans.

Subcontractor financing isn’t an obvious banking problem (look how long it took me to explain it to you!), so banks haven’t built a solution for it.

But that doesn’t mean someone couldn’t build a solution.

Materials Financing

Step one in solving this problem is recognizing that there is a very easy way to mitigate the risk of lending large amounts of money to subcontractors who, again, don’t always appear on the surface to be great credit risks.

The project.

If an electrician has a contract to do the wiring for a new office building being built by Amazon, that’s one hell of a reassurance that they will get paid for their work, and, thus, be in a position to pay you back.

Remember, anyone who does work or provides materials for that project will have a mechanic’s lien against that real estate. A mechanic’s lien against Amazon is basically the construction finance equivalent of a AAA-rated bond.

So, you start there. If you know that they have a contract to work on this project, you know there’s a very good chance they will get paid.

Step two is figuring out exactly how to insert yourself into the construction payments chain in order to best assist subcontractors in managing their cash flow.

One way to do that is to finance the materials. Materials make up, on average, 40% of a subcontractor’s total bid. Having to cover that 40% upfront for 60+ days (the 90+ day diligence process minus the 30-day payment terms offered by suppliers) puts a huge strain on subcontractors’ finances, making it more difficult for them to plan for the future and continue growing.

What if, instead, you directly buy the materials that the subcontractor needs to do the wiring on the Amazon office building? You pay the supplier cash upfront in exchange for a slightly lower price (they will be happy to do this if they don’t have to wait 30 days for payment), and you have them sign over their mechanic’s lien for the project to you (which you can use to backstop your risk). You transfer the materials to the subcontractor (this is technically an inventory trade credit, not a loan), and the subcontractor agrees to pay you a small weekly finance charge for 120 days, with a balloon payment at the end once they collect payment from the general contractor.

Pretty compelling, right?

The big challenge is step three – figuring out how to operationalize all of this.

The Operational Challenge

When you get down to the nuts and bolts of how to do this, there are some tough questions to answer, including:

How do you acquire all of these subcontractors?

The U.S. construction industry is incredibly fragmented. The top 400 contractors only account for about 20% of the market, meaning that there is a massively long tail of small contractors (especially subs) that you will need to figure out how to reach with this product.

How do you verify specific projects and the subcontractors’ involvement in them?

This is critical because you’re not trying to underwrite the subcontractor (although you will want to do some basic due diligence on them as well), you’re trying to underwrite the project. If a subcontractor has a contract to help build an office building for Amazon or a data center for Google or a retail store for Walmart, you need to be able to verify that.

Unfortunately, there is no national public database of active construction projects, and folks in the construction industry are very resistant to sharing any data that could be used against them (as you’ll know if you’ve ever tried to get a contractor to give you a precise bid on a project).

How do you collect payments from the subcontractors and manage your overall relationships with them?

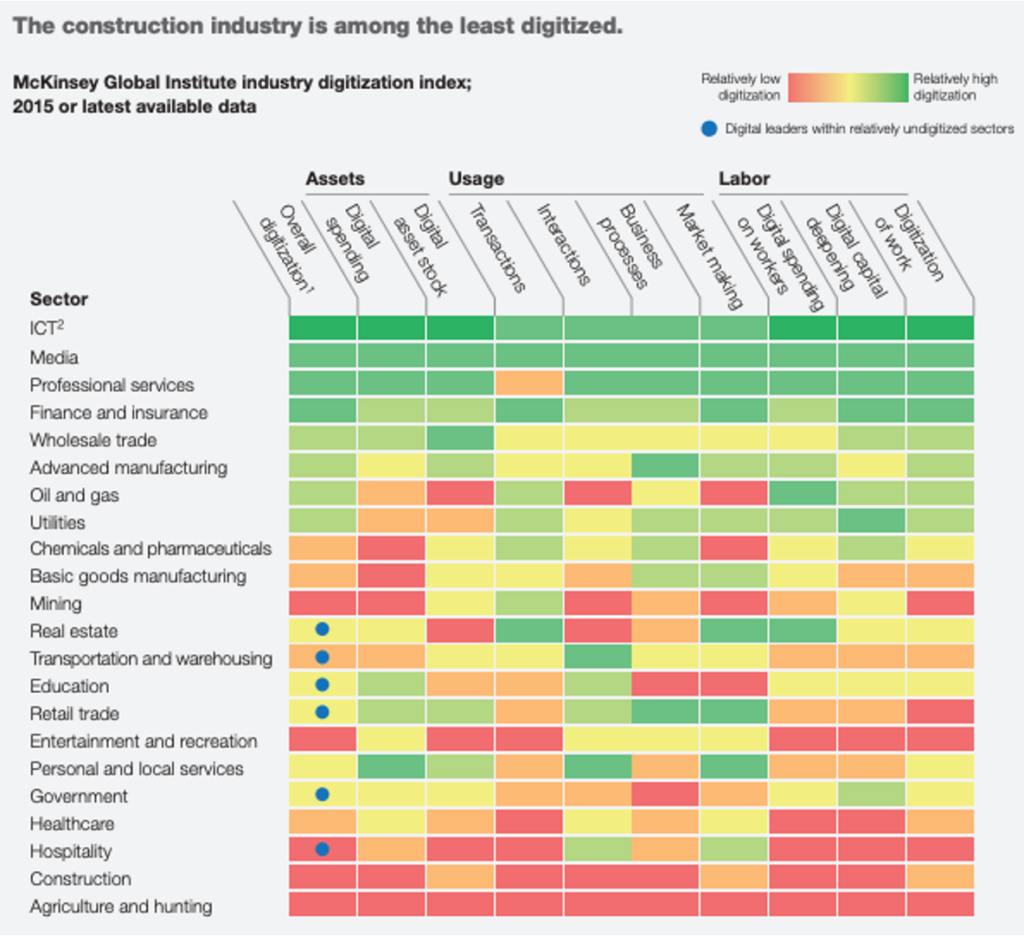

I know this seems like a very basic question, but I have to ask it because the construction industry is among the least digitized industries in existence.

This chart from McKinsey is a bit old, but striking nonetheless:

Embedded Finance for the Win

As you may have guessed by this point, my hyper-specific hypothetical materials financing solution for subcontractors isn’t, in fact, hypothetical.

It’s real! It exists!

It was (in the form that I described above) created by Procore.

Procore, if you’re not familiar, provides construction management software. It was founded in 2002 and has more than 13,000 paying customers (with a much larger base of users) across more than 125 countries. It is generally considered the most popular construction software provider in the U.S., having helped customers manage more than 1 million construction projects, ranging from residential remodels to massive commercial and government projects.

In 2021, Procure acquired Levelset, a provider of construction payments and lien process management solutions (this was the groundwork for its materials financing product). In 2022, the company formally announced that it would be expanding into fintech, seeing it as a major opportunity to grow revenue and create even stickier relationships with its customers and users. And earlier this year, Procore’s CFO (and a former investor at Bessemer Venture Partners), Paul Lyandres, stepped into the newly-created role of President of Fintech.

Now, it’s still very early in Procore’s history as a fintech company, but I think there are a few lessons we can take away from its efforts so far:

- Embedded Finance > Vertical Fintech Startups. There’s a big difference between identifying an unsolved, vertical-specific banking problem and actually solving that problem. To do the first thing, you need a deep understanding of the problem space. This is more common than you might think, as evidenced by the rapid proliferation of startups focused on solving problems at the intersection of fintech and construction. Actually solving the problems is a different matter, though. To do that, especially in an industry as fragmented as construction, you need distribution. This is why I think more established, vertical-specific software companies like Procore, which have already achieved significant scale, have a huge advantage over their fintech startup competitors. I expect that we will see many more acquisitions, across a variety of verticals, in the mold of Procore/Levelset.

- Data. Another advantage that large incumbents pursuing an embedded finance strategy have is data. Procore’s materials financing product wouldn’t work without Procore’s ability to quickly verify the projects that subcontractors are working on and the owners and general contractors that subcontractors are working for.

- Doing It Right Takes Time. We sometimes lump banking-as-a-service (BaaS) and embedded finance into the same general category. Understandable, but one key difference is speed to market. If you want to launch yet another debit card-centric neobank, you can do that really quickly (especially if you partner with a BaaS middleware platform). Building novel embedded finance products that solve previously-unsolved problems for your customers will take more time. There is no easy button to push. Procore has been working on its fintech strategy (which included an acquisition) for years, and it still has a long way to go.

- Fintech Job Titles. The fact that Procore’s President of Fintech was previously an investor at Bessemer (which was an early investor in Procore), didn’t surprise me when I learned about it. Bessemer is one of a handful of VC firms that has been thinking about embedded finance and the verticalization of fintech for a long time. There is obviously a lot of shared DNA between the two companies. As the concept of embedded finance becomes even more broadly proselytized, I’d expect that we will see a lot more job titles like “SVP of Fintech”, “President of Fintech”, and “Chief Fintech Officer” appear inside of large, established companies. (BTW – if you are reading this newsletter and you have one of these job titles, I’d love to chat with you!)

- Banks Need to Be More Curious. As I’ve explained, a bank could never build a materials financing solution the way that Procore has. They don’t have the same distribution and data. But I do think banks could stand to be a bit more curious about this stuff. If you have subcontractors getting turned away from your bank after begging for a line of credit to finance a new project they just landed, you should ask why. If you see your customers using your standard products (credit cards, HELOCs, etc.) in ways that they weren’t designed for, you should ask why. Your curiosity might lead somewhere productive!