The first law allowing no-fault divorces in the U.S. was passed in California in 1969. Before the passage of this law, if you wanted a divorce in California, you had to be able to demonstrate that your spouse was “at fault”, meaning that they had committed an act incompatible with the marriage (adultery, abandonment, etc.)

This wasn’t always easy to do, which made it difficult for people (women especially) to get out of their marriages on their own terms.

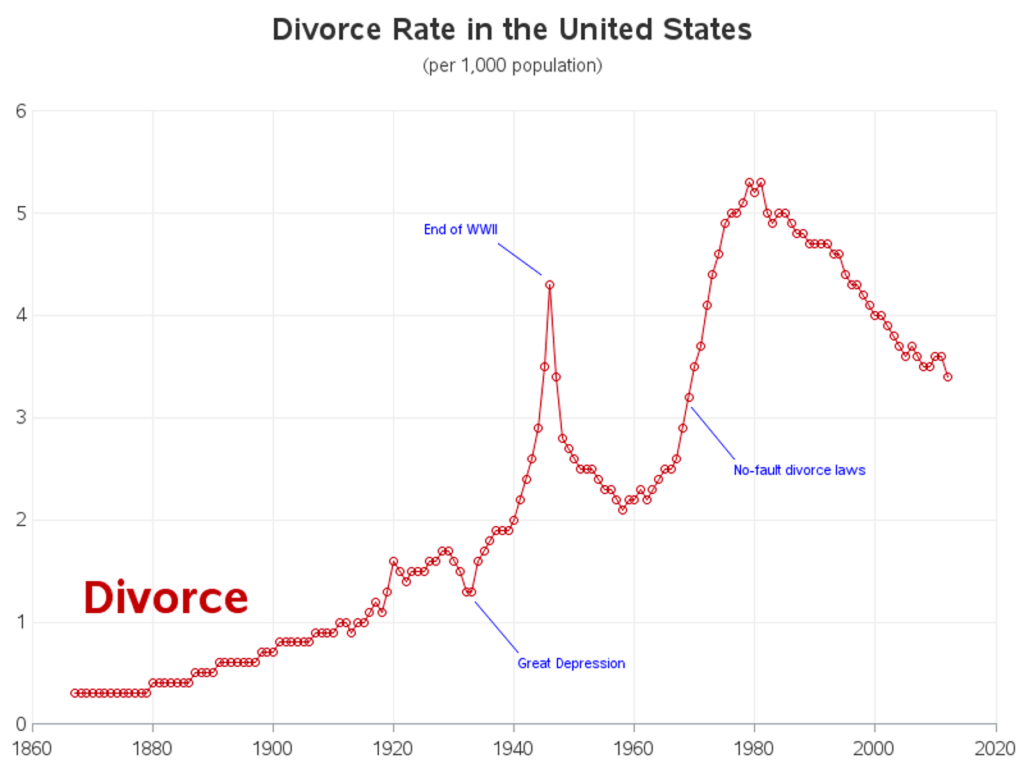

No-fault divorces, which were quickly legalized in much of the rest of the U.S. in the 1970s and 1980s, were a revolution. The legalization of no-fault divorces coincided with a massive surge in the divorce rate in the U.S.

Interestingly, researchers have found that there is no permanent effect of no-fault divorce laws on increasing divorce rates. When these laws were first adopted, divorce rates rose sharply in the two years that followed, reflecting a pent-up demand for divorce. But after 10 years had passed, the divorce rate went back to normal, or in some cases, compared with states without no-fault divorce, it fell further.

This suggests that no-fault divorce laws may actually lead to stronger marriages. No-fault divorce shifts the bargaining power to the person who is getting less out of the marriage and, thus, is most likely to leave. The partner getting more from the marriage has to work harder to keep the other person around, which can be good for the marriage and good for the couple.

Why is this relevant?

I think we’re right on the precipice of a “no-fault divorce moment” in financial services.

How Customer Retention Has Traditionally Worked in Banking

To some extent, every company screws over its existing customers in order to entice and reward new customers.

It’s basic customer acquisition arbitrage.

Retaining customers, even customers who aren’t perfectly satisfied, usually costs very little. Inertia and switching costs keep most people where they are. This basic reality allows companies to over-invest in the acquisition of new customers, even though that is, objectively, unfair to their existing customers, who provide much more value.

If you’ve ever switched mobile carriers, you’ll immediately understand what I’m talking about.

Every company engages in this arbitrage, but none more so than banks.

There’s not a ton of high-margin revenue in banking. Most profit in banking boils down to the difference in what it costs banks to acquire deposits and what they are able to charge customers for loans (net interest margin).

As a result, banks are absolutely ruthless when it comes to optimizing customer retention costs, to the detriment of those customers.

Research conducted by Allen Berger of the University of South Carolina and Troy Kravitz of the FDIC supports this:

We find clear evidence that an existing relationship with the issuing bank harms the depositor. Depositors with an existing transaction account with the issuing bank earn 13 bps lower interest on their insured CDs (17 bps on their uninsured CDs). Business accounts and depositors opening new accounts are particularly harmed by having an existing transaction account.

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

This is how banking has always worked.

But is it how banking will always work?

Maybe Not!

Thanks to online and mobile banking, it’s easier to move money today than it has ever been.

In theory, this should make it easier for customers to optimize their finances, at the expense of their incumbent banks. And indeed, this is a trend that researchers have noticed in the last decade.

According to an academic study published by the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State University of Chicago Booth School of Business, digital banking reduces the value of a bank’s deposit franchise by making it easier for its customers to chase rates:

Since the Great Financial Crisis, over half of the roughly 4,000 existing banks have introduced a mobile app. Thus, moving money from a deposit to a money market fund can be done with a single mouse click without leaving your sofa. As a result, it is reasonable to expect that the demand for bank deposits has become much more sensitive to the interest rates offered by alternative forms of liquidity storage (like money market funds), especially in banks with well-functioning digital platforms.

Having obtained an estimate for two of the key parameters of the … model of the value of deposit franchise, we can estimate that the value of deposit franchise is 40% lower in digital banks.

And it’s not just about shuttling money between accounts you already have in an effort to optimize yield. It’s also much easier today to move your entire primary banking relationship to a new provider if your old provider pisses you off.

This is the primary motivation driving the CFPB’s rulemaking on open banking in the U.S., and direct deposit switching, powered by open banking, is becoming an increasingly common capability at banks, both big and small.

And customers have plenty of incentive to consider switching, even if they’re not pissed at their current bank!

Thanks to the potent combination of interstate banking, digital channels, a massive influx of VC-funded fintech startups, and a multitude of financial product shopping and comparison websites, it’s incredibly easy for consumers and businesses to find financial services providers that are willing to offer them a better deal.

What Does All This Mean?

I’m not sure!

But it’s super interesting to think about.

Take deposits as an example.

“Hot money” is money that a bank brings in (often through third-party brokers) by paying above-market rates in order to address their liquidity needs. Hot money is obviously expensive (you are paying high rates to get it), but it’s also considered risky because hot money depositors are focused on maximizing yield and are, thus, more likely to leave if they can find an even better interest rate somewhere else.

In contrast, “core deposits” are generally seen as stickier and lower risk because the customers who are providing them are too apathetic to maximize their yield.

To put it in a relationship context, hot money is like the significantly more attractive person in a couple who just started dating. The other person in the couple knows that they are out-kicking their coverage and are going to be constantly worried about being broken up with if their partner finds someone hotter.

Core deposits are like the mildly discontent spouse in a long-term marriage in the 1960s, who would probably be happier if they were single, but isn’t willing to go through all the work to manufacture the grounds for an at-fault divorce.

Like no-fault divorce, digital technology and open banking have the potential to level the playing field for the average retail customer, who is under-appreciated by their bank, but unwilling to do the work to break up with them.

The implications of this are fascinating.

What if technology rendered the apathy, which makes core deposits so stable, obsolete? What if all money was hot money, by default?

How would banks create sticky customer relationships then?

My supposition is that banks would do what good spouses do today, in the world of no-fault divorces – they’d try harder!

On the most recent episode of the Bank Nerd Corner podcast, I complained to my co-host Kiah Haslett that banks’ bad habit of taking their most loyal customers for granted has prevented them from building the type of personal treasury management solution that I, as a customer, would want:

I want a bank to say, “We’re going to build a deposit service for you, Alex Johnson. And this service is gonna help you figure out how much money you need in your ‘operating account’ to pay your bills and cover everyday expenses. Then we’re going to have a range of different options for you, depending on your goals, for maximizing yield while keeping the money available to you for any uses that you may have for it. We’ll have a high-yield savings account, which pays X. We’ll have a CD, which pays a little bit more. We’ll have a range of investment and wealth management capabilities for when you’re feeling a bit more risk-on. And what we wanna help you do is constantly and intelligently optimize the deposits you have across all of these options. And guess what? When you put money into a nine-month CD, we’re not gonna hope that in month ten you just forget about it and the rate resets and we can sneak out a couple extra months of paying you nothing for your deposits. We’re gonna notify you immediately and help you find the next great place for your money to go.”

Doesn’t that sound great? Wouldn’t you marry that bank?

And what about on the loan side? Why don’t banks automatically help their customers refinance their debts? As Olivia Moore and Anish Acharya at Andreessen Horowitz recently pointed out, we have the technology to do it. Why haven’t banks built refi robots?

They can log into all of your online accounts, find the cheapest refi option for your debt, and execute the process of refinancing for you. An AI could go as far as filling out applications, canceling accounts, and originating new ones. It’s a massive step up from the data aggregators of the past.

We see this potentially manifesting in new products in a few different ways. There may be a “refi robot” consumer app, where consumers can connect their debt, add their personal credentials, and let the magic happen. We also expect infrastructure providers, including switching APIs and debt repayment platforms, to expose this automated refi capability to their end users—and take a tax on the transactions. Eventually, we could imagine a new kind of real-time auction spinning up, where credit facilities compete to acquire consumer debt.

Obviously, we know why banks haven’t built refi robots and personal treasury management services for their customers.

It hasn’t been in their best interests to do so.

That may be changing.

We may be entering the no-fault divorce era in financial services.

Wouldn’t that be exciting?