Everything in financial services is cyclical.

This makes intuitive sense. The purpose of the financial industry, speaking very broadly, is to facilitate economic activity. And the economy is cyclical.

When the economy enters a recession, delinquencies on loans to consumers and companies rise. Lenders shrink their credit boxes.

When the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates in order to spur economic activity, it reduces the costs of lending and encourages companies and consumers to borrow (and spend) money.

When a political party comes into power and wants to encourage economic growth, it deregulates the financial industry and frees it up to take more risks.

When excessive risk-taking by financial institutions (and their customers) causes economic harm, a different political party is voted into power with a mandate to derisk financial services through increased regulation.

The details vary, but the foundational cycles in financial services – in interest rates, credit quality, and regulation – remain the same.

In managing these cycles, we aim for gentle peaks and valleys. Policymakers try for soft landings. Regulators try not to overregulate. Politicians try not to screw stuff up when they’re going well.

We don’t always succeed. Sometimes we mess up the timing (rate changes and new regulations take a long time to work their way through our various economic systems). Sometimes the incentives for individual regulators and politicians lead to unwise choices (feel free to pick your own example here). And sometimes, something truly unexpected happens that changes everything all at once (as we all recently discovered).

What’s interesting to me is what happens when these peaks and valleys create vacuums in the market.

For example, what happens when new regulations designed to insulate banks’ balance sheets from their riskier tendencies lead those banks to pull back on lending to consumers and companies?

Do those consumers and companies just learn to live without?

Nope.

As Aristotle once observed, nature abhors a vacuum.

Where demand for credit exists, someone will step in to provide it. And often, they will do so using innovative new bits of financial and technological engineering that help push the overall lending ecosystem forward.

Which brings me to the central theory of this essay:

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

The evolution of the U.S. lending ecosystem in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis is a useful case study.

Intended and Unintended Consequences

In the lead-up to the Great Financial Crisis of 2007/2008, banks had gotten extremely clever at repackaging risk. Loaning out money to non-commercial grade companies (basically anyone except Microsoft or Johnson & Johnson) and non-conforming mortgage buyers (those whose mortgages couldn’t be resold to Fannie and Freddie) was a lucrative business. But it was constraining if you had to keep those assets on your books. So banks created asset-backed securities (ABS), which allowed them to pool those loans together, slice them up into different risk tranches, and sell them to secondary market investors. This allowed banks to offload these assets and turn around and originate more, which is exactly what they did. By 2007, banks in the U.S. had issued more than $4 trillion in ABS for corporate debt and non-conforming residential mortgages.

We know how this turned out.

And to prevent it from happening again, financial services regulators dropped a massive amount of new regulations onto banks’ heads. The big one was Dodd–Frank, which, among other things, mandated higher capital ratios for banks (especially for riskier asset categories) and restricted banks from engaging in proprietary trading and from owning, sponsoring, or having relationships with hedge funds or private equity funds.

The goal was to stop banks from engaging in the same types of risky lending and investing that got them into trouble the last time … and you know what?

It worked!

According to researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Dodd–Frank Act led to a meaningful reduction in both the number of bank failures (particularly among larger banks) and a reduction in the overall volume of loans made by banks (particularly small banks).

However, Dodd–Frank also led to something that its architects perhaps did not intend – the explosive growth of the private credit market.

What is Private Credit?

Private credit is a loan made to a private company by an investor or non-bank lender.

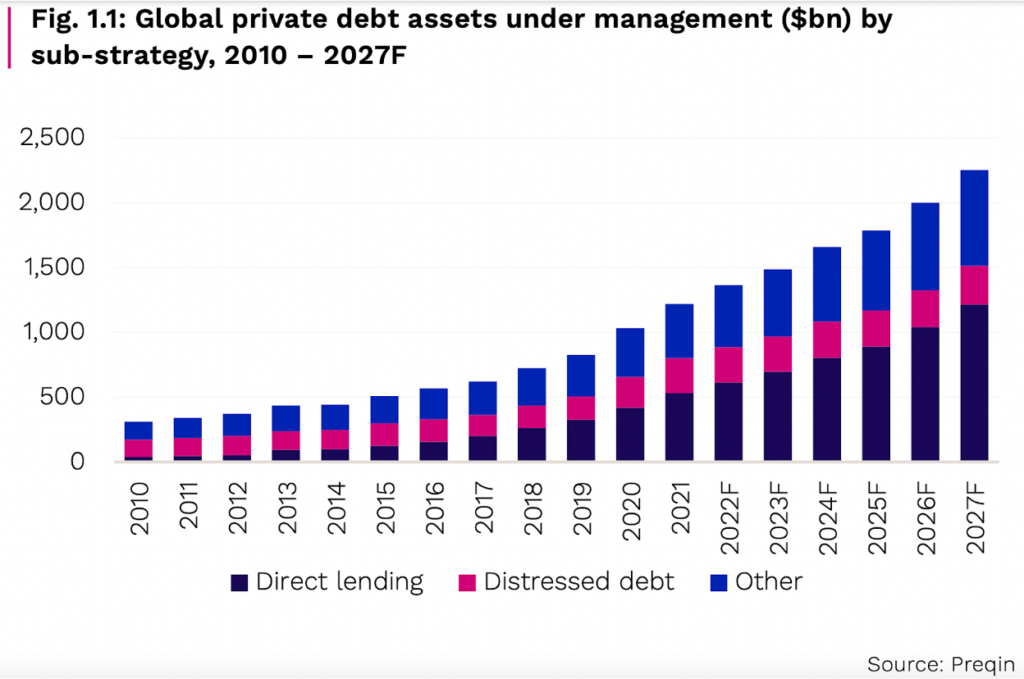

It’s not a new idea, but since 2010, it has become an extremely popular one. According to Preqin, an investment data company focused on the alternative asset space, the amount of money raised by investors for making private credit deals has increased from roughly $300 billion in 2010 to $1.2 trillion by 2021, and it is predicted to swell to $2.3 trillion by the end of 2027.

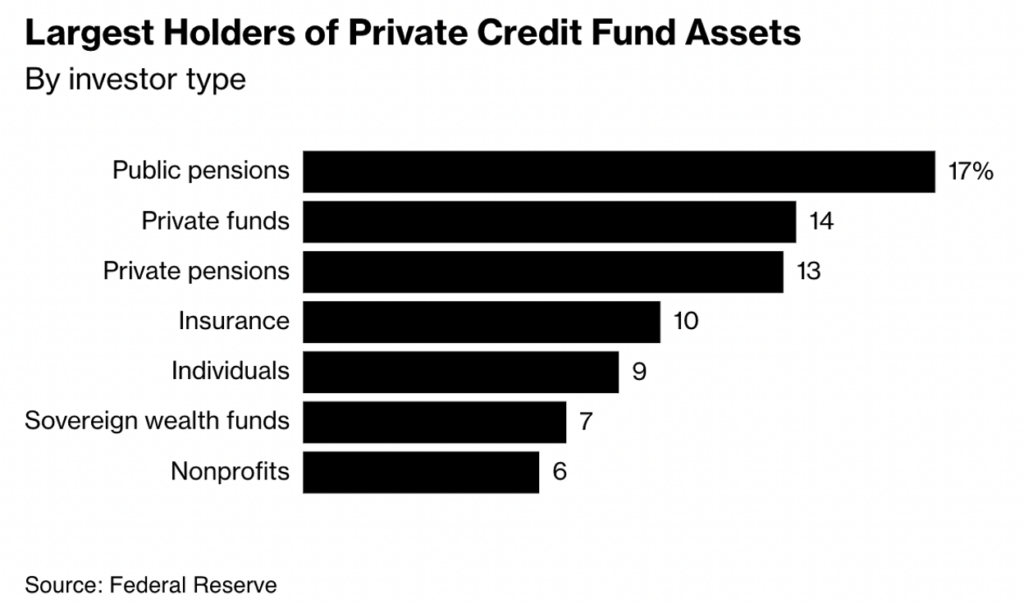

And who is allocating all of this money to these private credit funds?

Investors looking for yield, particularly (these days) public pension funds.

And while private credit really started gaining traction during the yield-starved days of 2016, investors have stuck around, even as interest rates have risen:

The industry took off around 2016, when interest rates were at rock bottom and investors were hungry for higher yields. But even now, with rates around 5%, private credit is going strong. It did well last year when almost everything else went south. While there is no index for the entire sector, the Cliffwater Direct Lending Index, which tracks nearly $280 billion of private loans to small and midsize companies, was up 6.29% in 2022. That compares with losses of about 19% for the S&P 500, 11% for junk bonds and 1% for leveraged loans.

Private credit loans almost always have floating interest rates, which means investors get paid more as rates rise.

The vast majority of private credit loans are direct loans, those made between private credit funds and small-to-medium-size companies (or the private equity firms that are trying to buy those companies). This makes sense, given that the demand for such loans grew alongside the growth of private equity (leveraged buyouts, baby!) at exactly the same time that banks largely retreated from the space.

However, a small but growing portion of the private credit market is made up of asset-based loans. As the name suggests, these are loans to companies where the companies’ assets are pledged as collateral. Those assets can be physical goods (real estate, aircraft, etc.) or financial assets (loans, receivables, royalties, etc.).

And here again, we see the fingerprints of the Great Financial Crisis.

Remember, according to that analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Dodd–Frank led to a reduction in lending, especially from smaller banks and especially for traditionally underserved customer segments like small businesses, young adults, and immigrants.

Who stepped in to fill that vacuum?

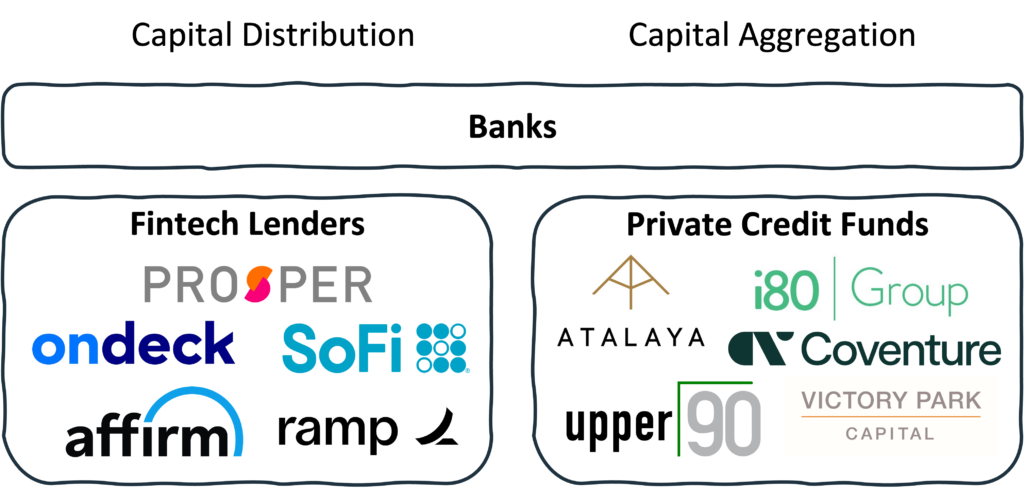

It’s actually a tricky question to answer because we have to account for the two different roles that banks have traditionally played in lending – aggregating capital and distributing capital.

On the capital distribution front, it was fintech lenders that stepped in. These companies, which had started to be founded in the years leading up to the Great Financial Crisis, really took off after 2010 with the rapid growth of P2P lending, small business lending, BNPL, and, most recently, corporate cards and spend management.

On the capital aggregation front, it took a little while longer for banks to be displaced. Even as they stopped directly distributing capital to underserved customer segments, the loans being made by the SoFis and Affirms of the world were still largely being funded – via asset-based loans – by banks like Goldman Sachs, Citi, and Cross River Bank.

However, in the last few years, even banks’ back-end capital aggregation role is starting to be usurped by private credit funds, which haven’t been slowed down by the same headwinds (rising interest rates, regional bank failures, etc.) that have impacted banks. Indeed, according to the CEO of a non-bank asset-based lender whom I spoke with, private credit firms’ share of the asset-based lending market has increased by nearly 50% since 2019.

If you’re a student of financial services history, you’ll know that this pattern of unbundling capital distribution and capital aggregation isn’t new. Specialty finance companies (and the investors that have funded them) have been around for a long time, and the prominence of their role in the industry has ebbed and flowed over the decades, just like everything else.

Again, everything in financial services is cyclical.

Except innovation.

The Opportunity to Improve Lending Accelerates and Compounds

The cyclical nature of financial services creates vacuums. In lending, non-bank lenders and private investors always rush in to fill such vacuums.

But the exact way they fill those vacuums, how they address the unmet needs of consumers, companies, and pension funds … that changes every time. It evolves. Because of innovation.

Marc Andreessen once observed that “Innovation accelerates and compounds, each point in front of you is bigger than anything that ever happened.”

If you look closely at the history of lending and specialty finance over the last 150 years, it’s hard not to agree with him.

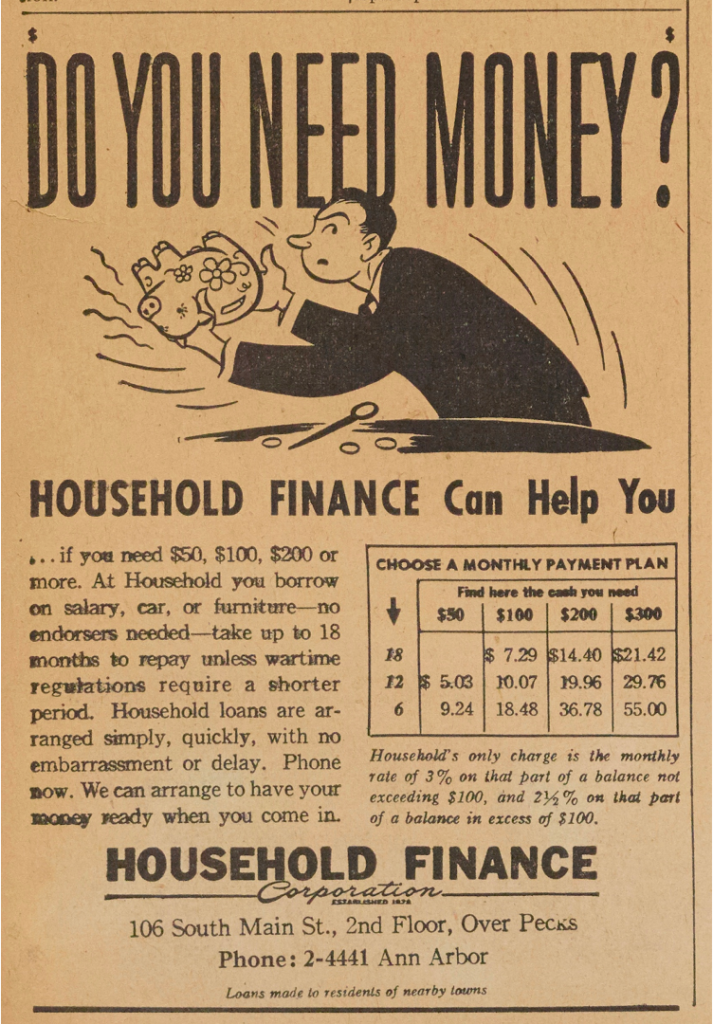

Household Finance Corporation (1878 – 2003)

In the United States, specialty finance got its start with a company called the Household Finance Corporation (HFC), which was founded in 1878 to democratize access to short-term financing for individuals whom the big banks, which catered almost exclusively to large companies and wealthy families living on the East Coast, were ignoring.

HFC was phenomenally successful. It grew to become one of the largest specialty finance providers in the U.S. It pioneered several huge innovations, including, most notably, the first direct mail solicitation for a consumer lending product (remember, this was in 1896). It expanded into virtually every new consumer lending product category that was created in the 20th century, including real estate secured loans, auto finance loans, credit card loans, non-conforming mortgages, home equity loans, and private-label credit cards.

In 2003, HFC was acquired by HSBC, and, over time, fully subsumed into HSBC’s consumer lending business.

Captive Finance (1903 – Present)

Several decades after the creation of HFC, we saw the introduction of captive finance companies in the U.S.

The basic idea here was that companies that sold things that their customers might not always be able to afford (i.e. most companies) would benefit from providing financing to their customers for the purpose of buying their products. Much of this financing was not available from banks because banks lacked a sufficiently detailed understanding of the assets in question and didn’t share the same incentive that the non-bank companies had to help sell more of their products.

Over time, these financing divisions grew big enough that it made sense for the companies to spin them off into separate, specialty lending companies that would remain ‘captive’ to the parent company and focus on helping them sell more.

The first example of these captive lending companies came in the automotive industry, where the big three automakers at the time (GM, Chrysler, and Ford) created captive auto finance companies (General Motors Acceptance Corporation, Chrysler Financial Corporation, and Ford Motor Credit Corporation) in order to enable car buyers to convert a lump-sum purchase into a down-payment and monthly installments.

And captive finance didn’t stop there. Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, we saw this model spring up in agriculture (John Deere Credit), aircraft and commercial equipment (General Electric Capital Corporation), and retail (Sears Financial Network), among others.

And similarly to Household Financial Corporation, these captive finance companies leveraged innovation to push the boundaries of lending forward. In 1934, American Airlines launched the Air Travel Card, one of the first charge cards ever created, which allowed customers to “buy now, and pay later” for tickets and receive a 15% discount at any other participating airlines.

Today, captive finance companies are still a significant force in the financial industry, although many have since been spun off or rebranded into entirely new companies (Discover, Ally, etc.)

Digital Lenders (2000 – Present)

And that brings us back to the modern fintech era, when low interest rates and reduced lending from banks opened the door to multiple waves of digital lending platforms, which, like their specialty finance predecessors, leveraged technological and financial innovations (the internet, automated credit decisioning systems, person-to-person marketplaces, etc.) to help push the boundaries of lending forward, yet again.

Helping Capital Aggregation Keep Up With Capital Distribution

Hopefully, after reading about the history of specialty finance in the U.S., it’s obvious to you the important role that innovation has played in the evolution of capital distribution.

What is likely less obvious to you (unless you’re even more of a financial services history nerd than I am) is the role that innovation has played in helping capital aggregation keep pace with the evolutions on the distribution side.

It took nearly 50 years of slow, careful organic growth for Household Financial Corporation to raise sufficient capital for it to scale its innovative approach to consumer lending nationwide. The only real mechanism for a company, at that time, to raise outside capital was for it to go public and start selling common and preferred equity shares, which HFC did in 1925.

Luckily for captive finance companies, they didn’t have to wait nearly as long. Through their associations with their well-established parent companies, captive finance companies had an advantageous starting position when trying to access capital markets. And they used this position to make the case to capital market investors that their parent companies’ assets (cars, tractors, aircraft engines, retail installment contracts, etc.) were worthy of investment-grade debt ratings and low interest rates. Thus was born the asset-backed security (ABS), a marvel of financial engineering that allowed specialty lenders to package together their loans into diversified securities for capital markets to invest in.

Mortgage-backed securities (which helped facilitate the Great Financial Crisis) are the bigger and better-known part of this market, due to the role of Government-sponsored entities in the secondary mortgage market. However, non-mortgage lending securities (ABS) have, by themselves, become a huge market. In 1985, the first non-mortgage asset-backed securities were issued, backed by consumer auto loans. That year, roughly $1 billion in ABS was issued. Today, that number is roughly $1.5 trillion, and it’s backed by every type of non-real estate consumer and commercial lending you can imagine.

And it wouldn’t have been possible without the cutting-edge technology of the 1980s, as this white paper from Magnetar Capital points out:

Technology has streamlined communications between dealmakers (think phones, faxes, … ) and provided the tools to rapidly price and measure risk. This has enabled deals to consummate at warp speed and in previously unimagined volumes. The growth of the securitization sector has relied on spreadsheet technology that emerged in the 1980s.

Innovation played a similarly important role in helping institutional investors effectively participate in the early days of the digital lending revolution, as this Forbes article explains:

Twice a day, at 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. Pacific time, Prosper Marketplace, an online service that connects small borrowers and lenders, posts a list of prospective loans for funding. That list is eagerly awaited by hedge funds and other institutions interested in making unsecured consumer loans at rates up to 32%. All the loans are snapped up within seconds.

That doesn’t leave much time for investors to look carefully for the ones that meet their risk and yield criteria. Which is where New York startup Orchard Platform comes in. Orchard builds software that buys loans and crunches all the data available from Prosper and other online loan marketplaces to analyze the performance of those loans over time. Today the company bids on loans for clients on three of the roughly two dozen U.S. online loan marketplaces and captures data from another seven.

What’s Next?

I want to end this essay by talking a bit about where lending, specialty finance, and private credit are going.

The Cyclical Outlook

I’ve given up trying to make political predictions, but even if we see a significant shift in party control after this next election cycle, I just don’t think there’s much of an appetite for significant regulatory relief for banks (particularly for large banks). The failure of Silicon Valley Bank was probably the moment that dream died, at least in the short term. We may see some tweaks around the edges, but I don’t anticipate any major swings in the regulatory cycle that would enable banks to claw back the market share that they’ve ceded to private credit funds and fintech lenders.

From an interest rate and credit quality perspective, private credit is holding up rather well. Higher rates equal more revenue (thanks to floating rates), and, so far, those higher interest expenses haven’t led to a significant uptick in default rates.

And to the extent that concerns over rising default rates cause investors to adjust their allocations, I’d expect that adjustment to happen more within the world of private credit, where we may see investment shift from large corporate loans to mid-size companies and PE firms to asset-based lending, where the pledged collateral can help offset concerns about rising risks. This would be a net benefit to fintech lenders, which rely on asset-based lending for funding.

Bottom line – the vacuum that created the modern private credit and fintech lending markets isn’t going away anytime soon.

The Innovation Outlook: Capital Distribution

Looking at the future of capital distribution, from an innovation point of view, it seems highly likely that, as Marc Andreessen might predict, we will see the evolution of lending accelerate rather than decelerate.

This will likely be achieved by a combination of vertical-specific software platforms (DoorDash, Mindbody, Shopify, etc.) and fintech enablers (Parafin, Stripe, Kanmon, etc.) that help those platforms embed bespoke lending products into their existing workflows and customer touchpoints.

As I’ve argued many times in this newsletter, embedded lending is the obvious and natural evolutionary endgame for capital distribution, which is why I tend to agree with predictions like this one from Bain Capital Ventures that the revenue generated by embedded lending in the U.S. will more than double from 2021 ($5.4 billion) to 2026 ($12.8 billion).

The Innovation Outlook: Capital Aggregation

I see a similar wave of technological innovation just beginning to swell on the capital aggregation side, which is good, as there are a lot of problems to be solved (and value to be created) in this area. It’s fair to say the biggest bottleneck in credit today is in the way fintech and specialty lenders access capital.

(Editor’s note – a common structure that is used by fintech and specialty lenders to access capital is a warehouse line of credit. If you want to learn more about what that is and how it works, Finley has a good explainer.)

Unless you’ve personally experienced it, it’s very difficult to understand how painful it still is to acquire and manage an asset-backed debt financing facility from an investment bank or private credit fund.

Luckily, Alex Song, VP of Finance and Capital Markets at Ramp published a wonderfully specific behind-the-scenes look at the process that Ramp went through to acquire its $150 million debt financing facility from Goldman Sachs.

It starts by pulling together all of the data that the bank or fund will need to see on the company and its assets (loans, in the case of Ramp). Here’s Alex:

They go through the entire value chain beginning to end and you need to explain how you originate the assets, how you service them, how you offboard customers. They will look closely at repayment behavior, timing, interruptions, delinquencies and cures. The lower the delinquencies, the better. We work with our friends at Finley to keep track of some of these KPIs for our portfolio of assets.

Ultimately, “return on asset” is probably the most important metric that a lender will consider. Put simply, is there enough cash flow to service and ultimately pay off the debt? Secondly, it’s critical for the company itself to be well capitalized with equity, just in case the assets underperforms expectations. Lenders want some capital cushion to support the debt and make sure they don’t get impaired if there is a hiccup in performance. As a rule of thumb, for every $10 of debt, you need $1-$4 of equity, depending on the asset being financed.

(Editor’s note – the need for some amount of equity financing to backstop debt financing for non-bank asset-based lenders is an interesting wrinkle. At the very earliest stages, lending startups will often use equity financing to fund the first few loans, just to prove out the model so that they can raise a debt facility. The role of VCs in getting the ‘loan origination flywheel’ spinning for non-bank lenders is absolutely critical, but, as we know, VCs’ appetite for investing in fintech and LPs’ appetite for investing in VC are somewhat cyclical.)

All of this data needs to be compiled by the company and made easily accessible and understandable for the bank or fund. As Alex explains, you want to spend a lot of time here, as you don’t get a second chance to make a first impression:

Our capital markets and engineering teams spent many weeks and months putting together a world-class data room. As a modern fintech company, Ramp believes strongly in the accuracy and fidelity of our data, and therefore spent a significant amount of time sanitizing and cleaning our portfolio data to put our best foot forward to potential investors. Every single calculation and data field was checked and re-checked multiple times. We cannot stress strongly enough on the importance of having zero error tolerance when building out the capital markets reporting function.

All of these data points and KPIs end up forming the basis for the credit agreement. This is the single document that governs the entire debt financing facility. It spells out, in excruciating detail, the terms of the arrangement, the responsibilities of both the borrower and the lender, and a huge number of covenants covering how every possible situation – from asset concentration risk to bankruptcy to a change in the borrower’s executive team – impacts the arrangement and the responsibilities of both parties.

It’s not uncommon for credit agreements to be more than 1,000 pages long (compared to typical documentation for an equity fundraise, which might be between 10 and 50 pages total) and, as the sole governing agreement for the facility, the focus of intense and lengthy negotiations.

(Editor’s note – here is a very well-written summary of what credit agreements are and how they work from Finley if you’re curious to learn more. And if you’re a glutton for punishment and want to see what a credit agreement actually looks like, take a look at this example from Dunkin’ Donuts.)

After the negotiations are complete and the facility is up and running, the credit agreement becomes the fulcrum for the administration and management of that facility, from both the borrower (who is looking to keep the facility up and running and in full compliance with the covenants of the credit agreement) and the lender (who is looking to identify and mitigate any risks as efficiently as possible, within the bounds of the credit agreement).

As you might imagine, that administration and management process, built around a legal agreement that is hundreds of pages long, is extraordinarily painful and operationally complex for both sides.

Noah Breslow, the former CEO of OnDeck (and now a Partner at Bain Capital Ventures), elaborated on this point when I asked him how OnDeck navigated the debt capital markets during his time there:

This industry has resisted innovation for a long time. Every bank and private credit fund does it a little differently. There are no standards for data exchange or for facility operations. At OnDeck, we built numerous systems from scratch to help us manage the back-end, operational mechanics of running a lending business. Specifically for credit facilities, at the end of my tenure, we had seven people working full-time with multiple homegrown systems to manage ten different credit facilities and all the attendant mechanics.

Fortunately, fintech innovation is finally starting to come to the capital markets part of the lending infrastructure stack.

On the front end, we are starting to see the emergence of modern tools for data wrangling, collateral analysis, and cash flow simulation.

On the back end, we are starting to replace spreadsheets and homegrown tools for facilities management with better, built-for-purpose systems for covenant compliance monitoring, borrowing base and transaction waterfall calculations, and portfolio and facility-level reporting.

Taken together, the rethinking of the “capital aggregation” technology stack is the part of the lending cycle that I don’t think we’ve seen before — the part that is harder to predict based on previous cycles.

The nature of specialty finance hasn’t changed over the past century: today’s specialty lenders offer consumers credit at the point of sale, just as their predecessors did. In the current iteration, however, consumers can access credit from their smartphone or from a checkout screen.

What is unprecedented, is how those capital distributors access capital. As private credit grows, it becomes more likely that fintech and specialty lenders get their funds from private funds, not banks. And as private credit technology advances, accessing institutional capital will become faster, easier, and more modular.

The result? We’ll see more companies like Ramp, which has already become a serious contender in the spend management space in the span of four years. The rate of software development, not capital access, will determine how fast fintech companies scale.

Creating Space for Innovation

Banks are the only companies that can function as both effective capital aggregators and capital distributors. This is why banks have always and will always play a central role in lending.

However, I would contend that the most effective environment for aggregating and distributing capital is one in which financial and technological innovations are able to flourish. And, ironically, that environment can only exist when banks take a step back.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Finley.

Finley is building software to accelerate the pace of capital, starting with tools for debt capital borrowers and providers. Finley’s software helps growing companies automate due diligence, ensure compliance, and streamline ongoing reporting with their capital providers. By bringing best-in-class technologies to a decades-old space, Finley’s software helps innovative companies and their lenders spend less time on routine tasks and more time on what matters.