You likely saw the news, first reported by my friend Jason Mikula over at Fintech Business Weekly, that Akoya (an open banking platform) and a few of the financial services companies that own it are making a rather aggressive move:

Fidelity, where Akoya was incubated, has taken by far the most aggressive steps to limit data sharing outside of Akoya. The brokerage serves 37.1 million retail accounts, 40.9 million workplace accounts, and 8.2 million accounts managed by wealth management firms and has some $10.3 trillion in assets under management.

Over the summer, Fidelity began notifying third-parties that access its customers’ data that they had until October 1 … to transition to Akoya or lose access.

Pittsburgh-based PNC Bank, which serves about 12 million retail customers, has also taken a fairly aggressive stance.

PNC initially gave some third-parties that access its data a deadline of November 1, 2023, to transition to Akoya before they’d be cut off.

After pushback from industry participants and, some sources suggested, conversations between the CFPB and PNC, the bank pushed back this deadline to June 2024.

Well, Fidelity went through with it, as this screenshot from Jason on October 2 confirms:

And from everything I’ve heard (which aligns very closely with Jason’s excellent reporting), PNC is still committed to following in Fidelity’s footsteps in June of next year.

You might be wondering why all of this is coming to a head now.

Well, it’s because the CFPB’s proposed rules on Dodd–Frank Section 1033, which will govern how consumer-permissioned financial data sharing will work in the U.S., are expected to be released very soon (I’m guessing Director Chopra is aiming for Money 20/20, but it’s possible it’ll be a week or two after the show).

It is, for fintech nerds, 1033 Eve!

And in honor of 1033 Eve, and the dramatic news that came out this week, I figured it would be a good time to publish my list of open questions about the future of open banking in the U.S.

#1: Will the CFPB Allow Akoya to Get Away With This?

Unlikely!

The bureau has made it quite clear that it’s not OK with middlemen restricting the free flow of consumer-permissioned data. Here’s Director Chopra writing about this exact concern in a June blog post:

In consumer finance, powerful firms have sometimes looked to manage emerging technologies through utilities, networks, or standard setting organizations skewed to their interests – or even owned by them.

Control of the open banking system by such players threatens competition and the consumer’s control of their own financial affairs.

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Reading between the lines a bit, I think this was the Director telling Akoya and Fidelity and PNC to knock this shit off.

He’s right to do it.

Forcing companies to go through a specific platform to access data and making those companies fully subject to the whims and pricing power of that platform would be a bad outcome for the industry, especially given that the platform in question is owned by a consortium of the largest banks.

My best guess is that the CFPB’s final rules will allow banks to select the utility provider that they want to use in order to enable data sharing (e.g. the company that provides the API for the bank), but the bureau will place some restrictions on what those utility providers can do. For example, contrary to the current arrangement between Akoya and Fidelity, I would guess that the rules will prevent the data access utility from charging a fee to the data recipient (e.g. the fintech or bank that is accessing the consumer’s data).

I’d also guess that the CFPB will impose some level of operational performance standards on the data providers. Akoya argued against service level agreement-type standards for API operational reliability in its comment letter to the CFPB on 1033, but what we’ve seen from the big banks in the UK on open banking API uptime suggests that some type of SLA is probably a good idea.

#2: How Will the CFPB Try to Move the Industry to APIs?

A couple of things that I know to be true:

- A goal of the CFPB, through its 1033 rules, is to end the practice of screen scraping.

- The CFPB views APIs as the preferred data access methodology for open banking.

There is broad agreement within the industry on these two points. No controversy.

What might cause some controversy is exactly how the CFPB goes about driving the transition from screen scraping (which is already being slowly phased out) to APIs.

From everything I’ve heard, the CFPB intends to delegate a lot of the ‘how’ of open banking to the private sector (kind of a big deal given Director Chopra’s general beliefs!) Assuming this is true, it’ll be interesting to see exactly who ends up driving the bus on some important operational decisions.

Take standards, for example. It seems very likely that the Financial Data Exchange (FDX) will end up being the technical standards-setting organization for open banking in the U.S. (unofficially or officially, I’m not sure). This is logical (FDX has been diligently working on an API standard for financial data sharing for a while now), but I can tell you that FDX is viewed with mild suspicion by data aggregators and fintech companies, which seem to think that the bank members of FDX may have undue influence over its priorities and direction.

Another question is whether the CFPB will require all banks, including community banks, to move to APIs. I would imagine that the bureau would be reluctant to impose significant technical costs on community banks, but I’m not sure if there’s a good alternative. Exempting banks under a certain size threshold (say $10 billion in assets) from needing to provide an API might, inadvertently, freeze community banks out of open banking entirely (especially if screen scraping gets banned). That wouldn’t be great for them or their customers.

#3: What Do Community Banks Think of Open Banking?

Speaking of community banks, I wonder what they really think of open banking.

Most community bank CEOs aren’t dumb enough to publicly say, “I truly believe it is my data and I don’t have to share it, and I don’t have to give it to my customers if I don’t want to.”

But, in their heart of hearts, do they agree with that sentiment?

The default big bank attitude towards open banking has always struck me as being something like, “We know how valuable our data is, and just because we have no intention of doing anything productive with it doesn’t mean that we are going to give it to these upstart competitors.”

I don’t think community banks share this sentiment. They don’t view their proprietary customer data as a competitive moat (they don’t have a lot of data science resources to throw at it), and their attitude towards fintech is more confused than it is angry (or, if they offer BaaS, delighted).

Two of the bigger concerns for community banks on open banking are, A.) the cost of supporting it (this can potentially be mitigated through integrations between the core banking vendors and the data aggregators), and B.) the shenanigans of the big banks through their consortiums (The Clearing House, which is owned by the big banks and deeply distrusted by community banks, is also a partial owner of Akoya).

If the CFPB can address these issues through its rules, I could see most community banks being relatively satisfied with the outcome.

#4: How Will the Fight Over Security Play Out?

This is where all the intense debates on open banking are taking place these days. Some questions that the kids are squabbling over right now include:

- When the consumer authorizes their data to be shared, where is that authorization happening? The answer today is on the front end, with the fintech company and the data aggregator that they are working with. This is convenient for the consumer (permission at the point of need), but the concern that banks have is fraud and data security. What if the consumer isn’t the one actually authorizing the request? What if it’s a fraudster? How confident can the bank be in the KYC and IDV processes that the fintech company and data aggregator are using? What if the aggregator is promising something wild and potentially risky, like passwordless-less data sharing? Or, alternatively, what if the consumer is legit, but the fintech app isn’t? Is the bank liable if the consumer shares their username and password with a fake or fraudulent app and something bad happens? Wouldn’t it just be safer, so the banks argue, to authorize data sharing to third parties through the banks’ secure customer portals?

- On a related note, once data sharing has been authorized, where does the consumer go to view, manage, and (where necessary) revoke third-party data access? There’s not a great answer to this one IMHO. Bank? Sure, but I have multiple banks, so that’s annoying. Fintech companies? I guess, but I’d really like to be able to manage multiple connections in a single place. Data aggregator? Possibly, but they don’t really have much of a consumer-facing brand, and there’s no guarantee that the fintech companies I choose to work with all use the same aggregator, so that’s also annoying. CRAZY IDEA – the CFPB should have a consumer-facing app that securely ties everything together and allows consumers to manage all the third parties accessing their data and, maybe, provides a centralized access point for monitoring their credit files, disputing inaccuracies, and submitting complaints. [Ducks to avoid objects thrown at head]

- How do existing data privacy and protection requirements, like those under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, apply to data that consumers share with financial service providers via open banking?

- How do banks’ third-party risk management requirements, which have been a recent focus of the prudential regulators, mesh with banks’ responsibilities under Dodd–Frank 1033 rules? An FAQ that the OCC issued in 2020 to clarify its 2013 guidance on third-party risk management specifically addressed open banking and data aggregation and definitely gave banks some ‘regulatory cover’ for imposing greater scrutiny on data aggregators in the name of information security. This guidance is now out of date, and I’m guessing that the CFPB’s rules (which are focused on consumer protection rather than safety and soundness) will have a slightly different take.

#5: What Does the CFPB Think of Individually-Negotiated Data Access Agreements?

Wherever consumer financial data is shared via APIs today, you can be sure that there are bilateral data access agreements governing it. These agreements are negotiated on a case-by-case basis between each of the data aggregators and the big banks.

I’m very curious to know what the CFPB thinks of these agreements.

On the one hand, when compared to Akoya’s brute-force strategy of requiring all data aggregators to sign a data access agreement with it (with no negotiation) in order to access data from Fidelity and (eventually) PNC, you could easily argue that the agreements that aggregators currently have with the big banks are a better alternative. By forcing everyone to hammer out individual agreements, you are incentivizing all parties to compete as rigorously as they can for the best terms.

On the other hand, I could see the bureau being a bit troubled by the unevenness and opacity of the current approach. What happens when one aggregator convinces a bank to allow something that it hasn’t allowed any other aggregator to do? Is it fair that the bank’s customers may get different experiences depending on the aggregator that their chosen third-party service provider uses? And what about smaller banks that lack the leverage to negotiate effectively with the aggregators? Are they simply at the mercy of whatever the aggregators are willing to offer them (or, more likely, offer their core banking vendor, which will be negotiating on their behalf)?

Really the core question here is this – does the CFPB want the data access layer of the open banking stack to be competitive and proprietary or more standardized and transparent?

#6: What Types of Data Will Be Covered Under 1033 Rules?

In his initial remarks on 1033 rulemaking, Director Chopra indicated that the final rules would cover transactional accounts, broadly defined:

We expect to propose requiring financial institutions offering deposit accounts, credit cards, digital wallets, prepaid cards, and other transaction accounts to set up secure methods, like APIs, for data sharing.

While we expect to cover more products over time, we are starting with these ones. Through these transaction accounts, the rule will be able to facilitate new approaches to underwriting, payment services, personal financial management, income verification, account switching, and comparison shopping.

I’m not sure the final rules will be so broad.

From the conversations I’ve had, it seems assured that checking accounts will be covered. Savings accounts (and other non-transactional deposit accounts) and credit cards also seem likely.

Other products, such as electronic benefit transfer (EBT) accounts and BNPL loans, seem less certain.

#7: Will the CFPB Consider Open Banking Data Aggregators Consumer Reporting Agencies?

OK, I’m cheating a bit here.

This isn’t part of the CFPB’s rulemaking on Dodd–Frank Section 1033. This falls under a separate effort, which is also underway at the bureau, to modernize how the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) is administered and enforced.

But it’s highly relevant! The core question at issue is this – which companies should be considered Consumer Reporting Agencies (CRAs) and thus subject to FCRA?

Most of the big open banking data aggregators have, for years, argued that the FCRA should not apply to them because, unlike the credit bureaus, they do not do any work “assembling or evaluating” the consumer data that they are facilitating access to. They are merely the dumb pipes transmitting the raw data; the digital equivalent of a consumer bringing in a shoebox full of bank statements into the branch.

It appears very possible that this rulemaking might not go the aggregators’ way:

The FCRA does not classify an entity as a consumer reporting agency unless it “assembles” or “evaluates” information on consumers. Although these terms have been the subject of scattered regulatory and judicial interpretation, there is significant uncertainty in the industry as to when a company’s handling of consumer data rises to the level of assembling or evaluating as opposed to acting as a mere conduit. The CFPB is proposing to eliminate that distinction in favor of treating any entity that acts as an intermediary in the transmission of consumer data from sources to users as engaged in “assembling” and “evaluating” within the meaning of the FCRA.

This makes intuitive sense to me. An open banking use case that all the data aggregators are excited about is cashflow underwriting, which is clearly a ‘permissible purpose’ covered by the FCRA.

If you’re going to supply data that drives lending decisions, you’re a CRA. Sorry.

#8: Will Consumers Leave Their Banks Over Open Banking?

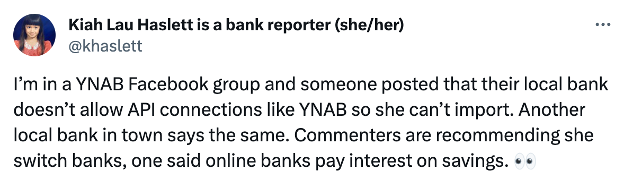

In a recently recorded episode of Bank Nerd Corner (coming out next week!), Kiah Haslett and I had a spirited discussion about personal financial management (PFM). It was prompted by a comment made in a YNAB Facebook group (Kiah is an adherent to the YNAB philosophy):

This is really the crux of the whole debate over open banking.

Consumers have come to rely on the fintech innovations powered by open banking. They don’t care about screen scraping or APIs or data access agreements. They just want the apps that they use to work.

The question is just how much do consumers care?

The evidence that I have seen (both quantitative and qualitative) suggests that if banks continue to fuck around with consumers’ ability to share their financial data, they won’t like what they find out.