For the last few years, banking-as-a-service (BaaS) has been one of the more interesting, drama-laden corners of fintech (BTW, that Jaws-esque music you hear in the background right now is Jason Mikula’s theme song).

Still, in that time, I don’t ever remember a week that was as bad for BaaS banks as last week was.

First, the FDIC made public a consent order with Choice Financial Group:

Choice Bank was hit with an enforcement action that it entered into in late December, and that was made public last Friday.

In Choice’s case, the action stemmed from a joint FDIC and North Dakota Department of Financial Institutions examination in June 2023 that resulted in a report of examination that concluded Choice violated certain provisions of the Bank Secrecy Act and the FDIC’s implementing regulations.

The enforcement action against Choice emphasizes the bank’s gaps in oversight and controls, including of third party fintechs with which it works.

And Blue Ridge Bank, which has been back peddling away from BaaS as quickly as possible since receiving an enforcement action from the OCC in September of 2022, just received a second such action from the OCC, not 18 months later:

The new consent order incorporates the elements of and replaces the prior formal agreement.

From the limited external information available, Blue Ridge seemed to be taking the right steps to address the issues raised in 2022’s OCC agreement.

It reshuffled leadership, bringing in veteran community banker William “Billy” Beale. It began the process of refocusing on its community banking roots and reducing its exposure to fintech partners. And it embarked on a $150 million capital raise to shore up its balance sheet.

But, evidently, these steps were not enough to convince the OCC that Blue Ridge had made sufficient progress on mitigating risks highlighted in the 2022 agreement.

In addition to requiring Blue Ridge to improve its BSA/AML compliance and third-party risk management, the order also continues to require Blue Ridge to receive OCC non-objection before onboarding new fintech partners or offering new products or services through existing third-party relationships.

The order also classifies Blue Ridge as being in “troubled condition,” which limits its ability to receive expedited review of certain regulatory filings and restricts golden parachute payments to bank executives.

Not good.

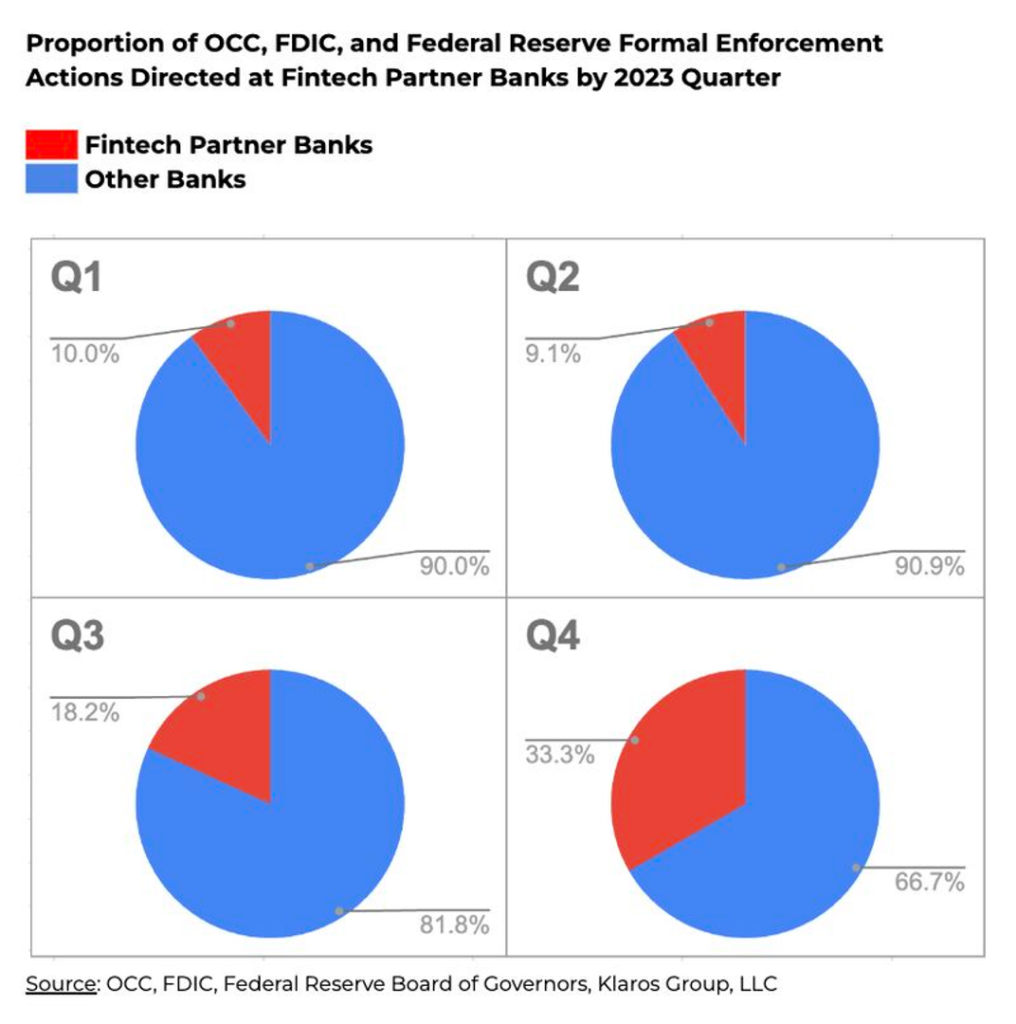

And lest you think that last week was an aberration, allow me to share this chart with you, courtesy of Konrad Alt at Klaros Group:

Fintech partner banks drew one-third of all formal enforcement orders by federal banking agencies in the fourth quarter of 2023. Reader: that’s a lot, especially when you consider that fintech partner banks only account for roughly 3% of all U.S. banks.

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

So, now seems a good time to pause and reflect on the state of banking-as-a-service.

Supply and Demand

BaaS is, at the end of the day, a market, and as such, it is best understood through the lens of supply and demand.

Despite the current regulatory headwinds in BaaS, I think there are a couple of fundamental reasons why we should expect the supply of BaaS providers to remain relatively strong for the foreseeable future:

- BaaS is still one of the best ways for community banks to grow. According to KBW, in 2003, banks with less than $10 billion in assets (which represented 98.8% of the U.S. banking market) controlled roughly 38% of all aggregate deposits. Fast forward to 2023, these banks still represented 96.6% of the market, but their aggregate share of deposits had fallen to 17%. This is the reason why community banks keep piling into BaaS, despite its many risks – partnerships with fintech companies and other non-bank financial services providers represent a reliable way for community banks to win in a market in which they have few structural advantages. Take deposit growth as just one example. According to S&P Global’s analysis of Q2 2023, community banks offering BaaS outpaced their peers on quarterly deposit growth, with a median sequential growth rate of 2.2% for BaaS banks in the second quarter and a decline of 0.8% for the rest of the US banks below $10 billion in assets. BaaS helps community banks attract deposits, earn fees, and diversify their balance sheets at a time when those three things are, for most community banks, practically impossible.

- Big banks are already doing BaaS and will likely do more. The Durbin Amendment is often cited as a major catalyst for fintech (and thus BaaS), and that’s true if you look at where the last major wave of fintech entrepreneurship started (B2C neobanks with debit interchange-focused business models). However, it’s a mistake to think that community banks have an exclusive right to win in BaaS, especially as other areas of fintech have become increasingly popular with entrepreneurs and investors (lending, B2B banking, embedded finance, etc.) Big banks like JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs have built robust businesses in areas like embedded banking and wholesale payments (Goldman’s senior partners don’t appear to have a stomach for continued investments in its Transaction Banking business, but that shouldn’t be mistaken for proof that the model didn’t work). Fifth Third is well on its way to joining them with its Newline business (building on its string of recent fintech acquisitions). More will follow.

On the demand side, I’m also somewhat optimistic because:

- Entrepreneurs will continue to want to create better banking experiences, which means that they’ll need to partner with banks. Despite a slowdown in VC funding in fintech in the last 18-24 months, entrepreneurs will continue to be drawn to financial services as a place to build. The emergence of embedded finance will continue to lead new non-bank product and service providers, across a huge range of industries, to bolt financial services onto their existing offerings. And so long as U.S. policymakers and regulators continue to make it virtually impossible for startups or large non-bank companies to directly get bank charters through the de novo route, special-purpose charters, or acquisitions of already-chartered institutions, there will be little choice for these companies but to work with BaaS banks. This isn’t the most logical system for ensuring a steady supply of new competition in financial services, but it’s good for the BaaS market.

That said, I have one small caution on the demand side of the BaaS market:

- It is possible for large non-bank companies to do some banking stuff without banks. There are BaaS alternatives (money transmitter licenses, lending licenses, etc.) that allow non-bank companies to get “closer to the metal” for certain financial services. While these alternatives don’t cover everything (you still need a bank license to hold deposits or issue debit or credit cards, for example), they do provide an option for motivated non-bank financial service providers to offer certain products and services, at superior unit economics, without a BaaS bank partner (or with a BaaS bank partner playing a significantly reduced role). I see this path becoming slightly more popular for large and successful non-bank companies over the next five years.

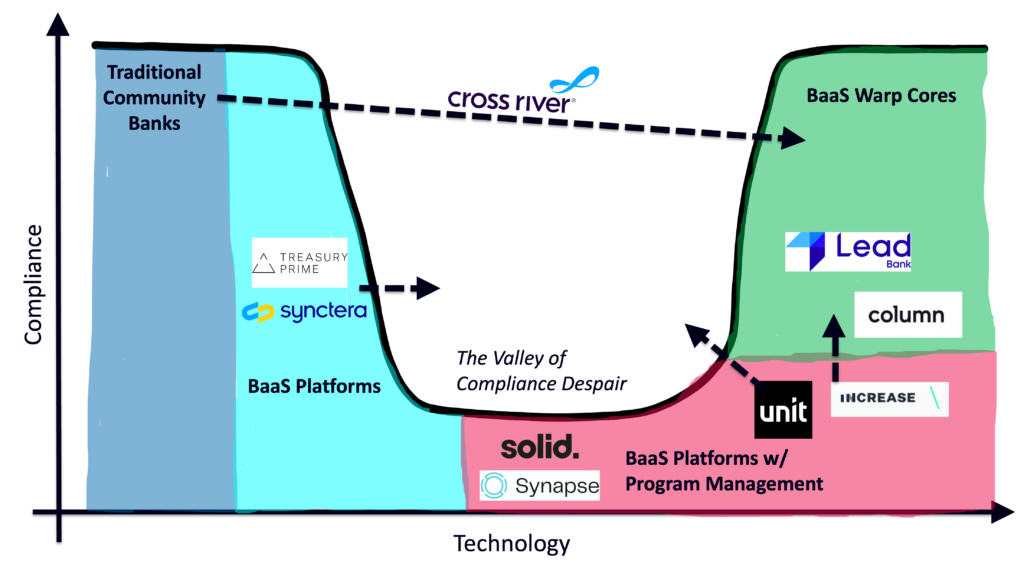

A Review of BaaS Models and a Visit to the Valley of Compliance Despair

Now, let’s review the various delivery models for banking-as-a-service, which will also serve, roughly, as a quick tour of the last 15 years of BaaS history.

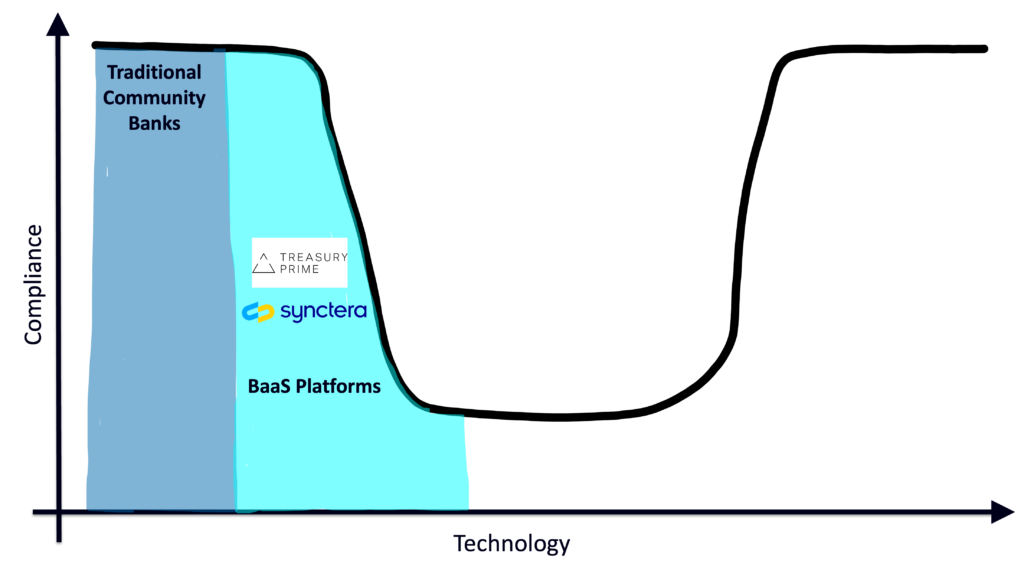

First, it is important to note that the ideal BaaS solution is one that optimizes both the technology and compliance sides of the business.

The need for technology is obvious. Fintech startups and the vast majority of large, non-bank companies interested in embedded finance are, in their DNA, software companies. Developers are the ones steering the ship. They want and expect to work with modern tech platforms featuring easy-to-play-with sandboxes, robust APIs, and clear, comprehensive documentation.

Put simply, they never ever want to see or touch a core banking system.

The need for compliance is, on the surface, less obvious, but (as we’ve all discovered recently) much more important. In fintech and embedded finance, your bank partner is existentially important.

If your bank runs into a compliance problem and is forced to offboard you, there’s nothing you can do to stop it, regardless of how diligent you yourself have been on all things compliance. Amanda Peyton, founder of B2C fintech app Braid, summed this up well in an essay last year:

As a startup, we were a tiny rivulet downstream of the ocean that is the U.S. financial system. When the dam broke, we learned very quickly that no one cared about our perfect, squeaky-clean BSA audit.

So, that’s our North Star – a BaaS solution that provides an optimal blend of technology and compliance.

However, just because we’ve known where we needed to go, doesn’t mean that it has been easy to get there.

The journey started with traditional community banks (circa 2009) and the creation of Simple and PerkStreet, two of the first neobanks in the U.S.

The few community banks that agreed to work with this first generation of neobanks – your Bancorps and MetaBanks – were pioneers. They took their lumps (The Bancorp and MetaBank, now known as Pathward, both dealt with consent orders in the 2010s), but, in doing so, they helped to establish the blueprint for what a direct fintech-bank partnership looks like.

The challenge was scalability. None of the early BaaS banks had infrastructure that was particularly well-suited to supporting a large number of fintech programs. And the barriers to entry for new community banks getting into BaaS were simply too high to allow for a meaningful increase in supply.

This was problematic because demand for BaaS, fueled by ZIRP-inspired mania in the fintech VC community, was starting to explode in 2018/2019.

The market needed a new solution, and it got one – BaaS Platforms.

We’ve talked about BaaS Platforms a lot around here over the last few years, but here’s a quick refresher – BaaS Platforms are middleware providers that connect banks looking to offer BaaS services with fintech companies and other non-bank financial services providers looking for bank partners.

All BaaS Platforms provide the same two core value propositions – technological agility (APIs, ledgers, and payment processing capabilities make it faster and easier for banks and fintech companies to integrate and get into production) and matchmaking (BaaS Platforms help connect fintech companies with the BaaS banks in their networks that will be the best fit for the fintechs’ goals and product roadmaps).

Where the BaaS Platform market starts to get interesting is when you add in program management.

In the U.S., banks are responsible for ensuring that everything facilitated through their charters is done in full compliance with all applicable laws and regulations. Banks design their risk, governance, and compliance processes and systems in order to guarantee that they are consistently meeting this obligation.

When a bank is working directly with third-party partners like fintech companies or non-bank embedded finance providers, it will extend its risk, governance, and compliance processes and systems to cover these partners (in much the same way that it would if it expanded its geographic footprint with a new branch).

Some BaaS Platforms – such as Synctera and Treasury Prime – are built around this approach. They help their banks and fintech companies find each other and integrate their systems, but they don’t attempt to play any type of intermediary role when it comes to risk or compliance operations. They get out of the way and let the bank and fintech company work everything out directly. This isn’t a lot of fun (for either the BaaS banks or fintech companies), and it’s not terribly efficient, but it is relatively safe from a compliance perspective.

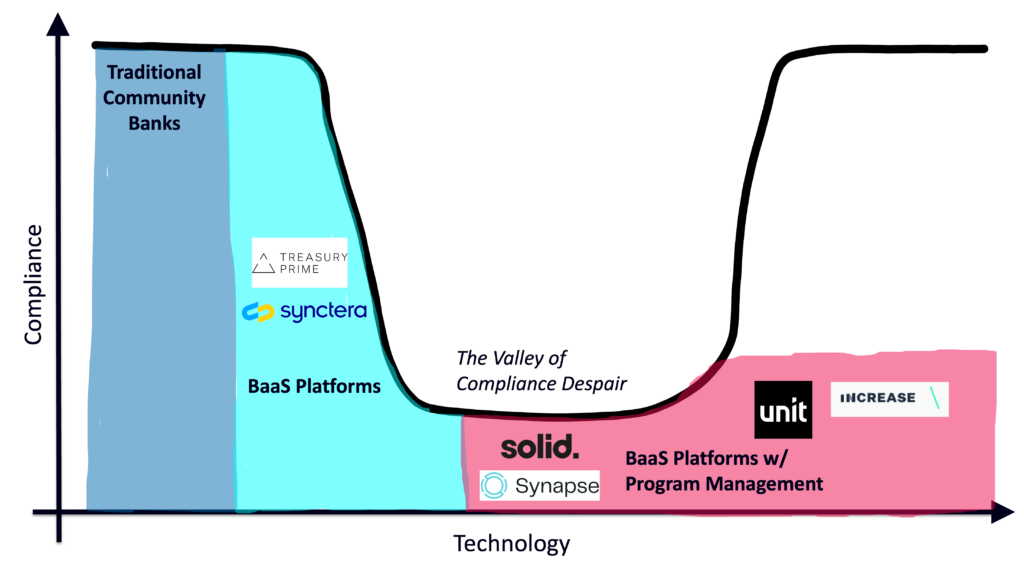

Other BaaS Platforms take a more hands-on approach.

In this model, the bank leans heavily on the BaaS Platform for a lot of the day-to-day risk, governance, and compliance work. The platform acts as both the technical and operational interface between the bank and its fintech programs. The bank gets some high-level reports on what its fintech programs are doing, but otherwise is fairly hands-off. The fintech company is similarly abstracted away from the bank and is given a bit more control to design onboarding and transaction monitoring processes that will create great experiences for its customers. The BaaS Platform is the program manager.

Solid, Synapse, Unit, and Increase are all examples of BaaS Platforms that have, to varying degrees over the last several years, provided program management (along with matchmaking and technical integrations).

It’s important to note that program management provides a lot of value to fintech companies and non-bank embedded finance providers. Remember, these are software companies. Software developers don’t want to work with bankers. They don’t want to talk to bankers. They don’t want to be told by bankers why the thing they want to do is technically feasible but probably too big of a risk. Developers just want to be given a sandbox and a set of APIs and to be let loose to write and ship code.

Program management, when combined with a modern technology platform, delivers the BaaS experience that software developers strongly prefer.

And program management works well in certain corners of financial services. Program management is a model that has worked in card issuing, for example, where a bank may act as a BIN sponsor for a non-bank card program but outsource a great deal of the operational and compliance work to a third-party program manager.

However, the reason that program management works in card issuing and BIN sponsorship is that it is a very narrow, well-established space with a lot of built-in controls and risk monitoring (much of which flows down from Visa and Mastercard).

The problem with BaaS is that it is decidedly not a narrow, well-established space with a lot of built-in controls and risk monitoring. Quite the opposite!

Which brings us to …

The Valley of Compliance Despair

The majority of BaaS banks that have gotten into regulatory trouble in the past couple of years have been working with a BaaS Platform that provided some level of program management. Here’s just a sampling:

- Increase – Blue Ridge Bank

- Unit – Blue Ridge Bank, Choice Bank

- Synapse – Evolve Bank & Trust, Lineage Bank

- Solid – Evolve Bank & Trust, CBW Bank

The proximate cause of these problems varies. Sometimes it’s the platform playing fast and loose with the program onboarding and oversight processes. Sometimes it’s the bank treating BaaS like a free money machine rather than as a new high-risk line of business that needs to be carefully managed. And sometimes it’s the fintech company executing a crazy pivot and not bothering to tell their platform provider about it.

The ultimate cause, however, is consistent – BaaS Platforms that provide program management tend to attract fintech companies and BaaS banks that are looking for the easiest and lowest-cost path forward, and those characteristics tend to be associated with a higher level of regulatory risk.

And regulators have noticed this. One of the most common hallway conversations at Money 20/20 last year was about the hardening attitude among prudential regulators about BaaS program management. Here’s what I wrote in my event recap:

There seems to be a belief among regulators that any BaaS middleware model that includes significant program management or that attempts to obfuscate the relationship between the bank and the non-bank partner is fundamentally flawed and incompatible with satisfactory third-party risk management.

How are BaaS Platforms reacting to this shifting regulatory stance? How are they trying to escape the Valley of Compliance Despair?

Well, some of them are engaging in protracted legal battles with their clients and investors.

Some are attempting to soften their approach to program management in order to mollify regulators’ concerns (for example, moving from bi-party agreements with fintech companies to tri-party agreements with fintech companies and BaaS banks).

And one tried to buy a bank!

Washington Business Bank, to be precise:

Washington Business Bank announced today the signing of an agreement pursuant to which an investor will seek to acquire 100% of the shares of WBB through a tender offer to all its shareholders. Pursuant to the agreement and subject to regulatory approval, the investor will offer $30.00 in cash for each share of WBB common stock.

The investor in question was Darragh Buckley, the first employee at Stripe, who left in 2016 and founded Increase in 2020.

Increase, which has partnerships with Blue Ridge and First Internet Bank, is generally considered to be one of the most modern, developer-centric BaaS Platforms in the market. This shouldn’t come as a surprise given Buckley’s experience at Stripe, and it is the primary reason that Increase has been able to land a number of brand-name fintech clients, including Pipe, Gusto, and Ramp.

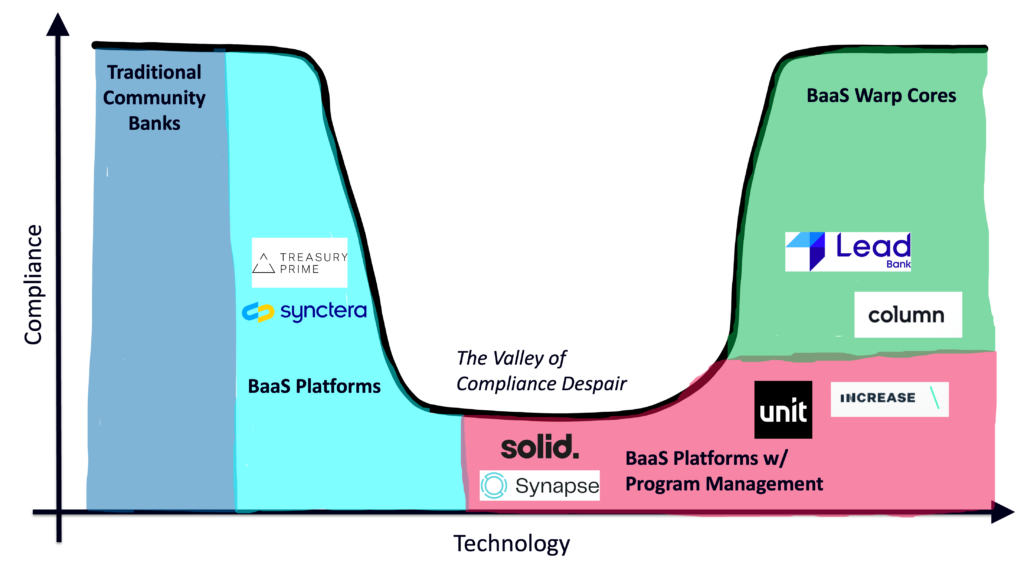

In seeking to acquire Washington Business Bank in May of 2022, Buckley and Increase were trying to ascend to the other side of the Valley of Compliance Despair. They were trying to become a BaaS Warp Core.

What’s a BaaS Warp Core?

In theory, it’s the best of both worlds – a world-class technology platform that delivers an exceptional developer experience, built directly on top of a community bank charter and balance sheet.

There are two BaaS banks in the market today that meet this description – Column Bank and Lead Bank.

Column was launched in 2022 by William and Annie Hockey. William Hockey was previously the co-founder and CTO of Plaid, a role that he stepped down from in 2019. In 2021, the Hockeys purchased Northern California National Bank, a tiny community bank based out of Chico, California, for $50 million and spent the next year building a brand new technology platform, optimized to support fintech developers looking to build B2C or B2B banking or payment products.

Lead Bank is, at a high level, a similar story. The community bank, based in Kansas City, Missouri, was purchased by Jackie Reses (backed by a group of investors) in August of 2022 for $52 million. Prior to acquiring Lead, Reses was at Square, where she led the company’s small business lending unit (Square Capital). In 2017, Reses and the team at Square undertook the effort to acquire a Utah-based Industrial Loan Company (ILC) charter, an effort that succeeded in 2020, the same year that Reses left the company. Since 2022, Reses has transformed Lead into a technology-centric BaaS bank, specializing in the same business that Square Capital was in – lending.

BaaS Warp Cores are appealing because, like the engines of the USS Enterprise, they allow fintech companies to move fast.

This is especially appealing to the largest and most sophisticated fintech companies in the market. At these companies, the decision on which BaaS providers to work is made by the engineering teams. These teams want to work with BaaS providers that can match their engineering velocity, and that will expend the necessary resources to implement exactly what they want (these fintech companies don’t pick off of a menu, they expect custom implementations). They look for technical credibility, above all else, which is an advantage that these well-known executives from Stripe, Plaid, and Square lean on heavily to help their companies win business.

Brex (Column), Affirm (Lead), and Ramp (Lead & Increase) are all major fintech companies that have gone this route.

The challenge with BaaS Warp Cores is that you have to maintain the precise right balance between your technology, regulatory compliance, and balance sheet, or, much like on the USS Enterprise, the matter–antimatter reaction can become unstable and result in a massive explosion.

Maintaining that balance is difficult. The folks running these BaaS providers are extremely confident in their ability to serve the largest and most demanding fintech companies in the market. As fintech veterans themselves, they have a bias towards action and moving fast. This mindset, if not properly calibrated, can rub bank regulators (the antimatter in this analogy) the wrong way or even scare them enough to pump the brakes.

After a splashy public launch in April of 2022, Column ran into some regulatory headwinds, which caused the company to cut back on the number of new clients it was onboarding and to focus its resources and attention on a smaller number of large clients in the B2B banking and payments space (Brex, most notably).

Around the same time, Washington Business Bank repeatedly delayed its sale to Darragh Buckley due to concerns from the FDIC. Ultimately, the acquisition was called off when it became clear that regulators would not approve it, and Buckley settled for taking a small ownership stake and a board seat.

Even Lead Bank, which, from what I can tell, has taken the most compliance-forward approach to building a BaaS Warp Core, has been flirting with businesses that bank regulators aren’t wild about, as Forbes recently reported:

In early 2023, Lead partnered with bitcoin storage company Unchained in spite of the apparent disdain federal regulators have for cryptocurrency-related firms and activities. In February, crypto investor Nic Carter tweeted about regulators joining in a “well-coordinated effort to marginalize the industry” and cut it off from the banking system that he dubbed “a new Operation Choke Point.” Unafraid of any backlash, Reses replied to the post, “We can help on the core banking products not crypto custody.”

Can Anyone Win?

Hopefully, this essay has demonstrated just how precarious BaaS, as a business, has become. One of the folks I spoke with while researching this piece described it as an anti-network effect business, meaning that the value of your service actually goes down as more programs use it (because each new program adds compliance risk for the BaaS provider and the other programs already relying on it).

This isn’t a winner-take-all market. This isn’t a winner-take-most market. Heck, if prudential bank regulators keep pushing in the direction and with the force that they’ve been pushing lately, this might not be a market at all in the near future.

Assuming regulators stop short of that, however, how should current and aspiring BaaS providers think about navigating this increasingly fraught ecosystem?

I truly, sincerely, do not know. And anyone who tells you that they do know is full of shit.

That said, here are a couple of ideas, loosely held:

- If you’re a traditional community bank, you’re either going to want to try to cross the chasm and develop a technology platform that is somewhat comparable to what Lead, Column, and Increase have built (Cross River Bank, having raised $620 million from investors in 2022, appears to be taking this approach), or you’ll want to develop a high level of competency and risk tolerance for a specific BaaS market segment that is underserved (cannabis, cross-border payments, adult entertainment, etc.), which will give you leverage with fintech partners and BaaS Platforms.

- If you’re a BaaS Platform, you’ll want to figure out a way to develop a better experience for developers and software engineers (if you don’t provide program management) or a more appealing (in the eyes of regulators) approach to compliance (if you do provide some level of program management). In both cases, you’ll also want to recruit additional bank partners.

- If you’re Solid or Synapse, you hope for good luck with your ongoing legal battles.

- If you’re a rich tech executive interested in buying a community bank and building your own BaaS Warp Core, you hope for a regulatory environment that is more accommodating of your ambitions. (A name to watch in this space is Brian Barnes, founder of M1 Finance. Barnes successfully bought the First National Bank of Buhl in 2021 and is in the process of building a competitor to Column and Lead. However, his rebranded bank – B2 Bank – just received an enforcement action from the OCC in December, so it might be slow going for a while.)

- And if you’re a BaaS Warp Core, you keep doing what you’ve been doing – cherry-picking the very best fintech partners, carefully managing your balance sheet, and keeping your head down with regulators.