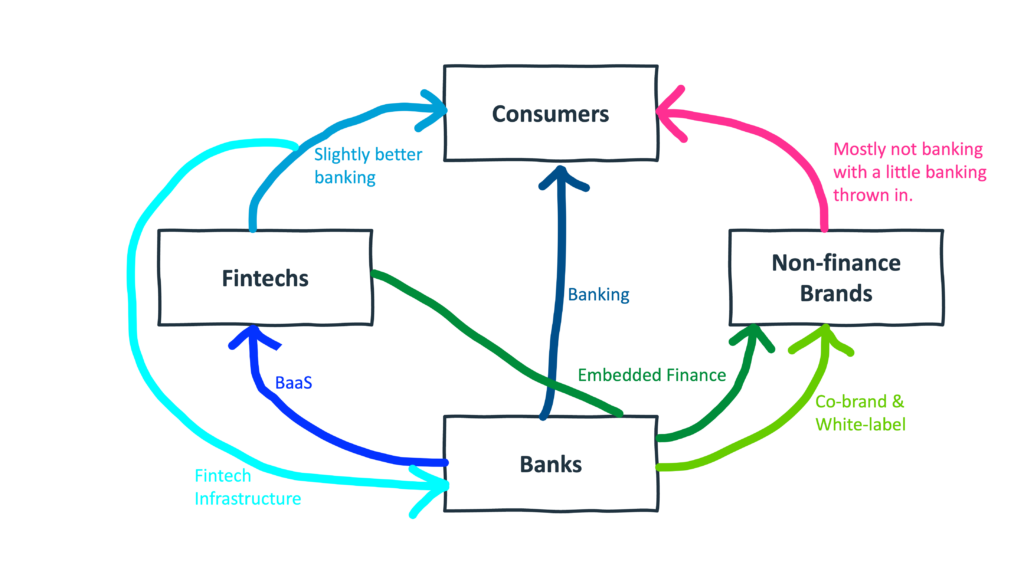

Here’s a very rough model for how B2C financial services works today:

Banks provide banking products and services to consumers.

A small (but growing) portion of banks provide banking-as-a-service capabilities to fintech companies.

Fintech companies provide slightly better banking products and services to consumers.

Banks provide co-brand and white-label banking products and services to non-finance brands.

Fintech companies provide embedded banking products and services to non-finance brands

(Editor’s Note – Embedded finance and co-brand/white-label are very similar. The difference is that embedded finance is enabled by the ease of integration with software products and platforms and is driven more by fintech than by banks.)

Non-finance brands provide mostly-but-not-entirely-not-banking products and services to consumers.

A small (but growing) portion of B2C fintech companies (or operators at those companies) tire of selling directly to consumers and decide to pivot into selling their tech and expertise to banks (and other fintech companies) as infrastructure.

This model covers all of the important dynamics in B2C financial services today.

Well, almost all of them.

Aim Small, Miss Small

Ayo Omojola, founding product manager on Cash App’s banking team and writer of infuriatingly insightful essays, published a piece last year titled, “Subtle Differentiation (or why there are no 10x products in fintech)”

The core premise of the piece is that differentiation – doing something materially different and better than others – is achievable at an incremental level in financial services, but not at a 10x level:

Paying $0 to trade stocks is definitely better than paying $7 per trade, but it’s incremental, and once you hit $0 you can’t sustainably go lower without destroying your unit economics. Giving access to paychecks 2 days early is definitely better, but once you hit 0 days, you can’t sustainably go lower without taking credit risk. Faster paychecks and lower cost trades are definitely better, but they’re not like “iPhone beats Motorola RAZR” or “reusable rockets” better.

Instead, Ayo proposes that success in B2C financial services is usually the result of subtle differentiation:

In the early days of the Cash Card, people sometimes asked why anyone would choose the Cash Card over a BofA card (in a lot of cases they’d also ask why anyone would choose Cash App over Venmo). I thought a lot about how to answer this, and within the 10x model for differentiation (which was dominant in 2015, and I think remains dominant in software industry narratives to this day). I didn’t have a good answer. My answer at the time was that we weren’t going to be 10x better at one thing, because it just wasn’t possible. But we could be 2x better at 10 things.

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

This approach can work, but it’s not without its challenges.

One of the big ones is that it takes time to get different customer segments to understand and try out your subtly differentiated product, and then more time to introduce enough 2x benefits to start seeing compounding returns:

When you build something that’s subtly differentiated, you spend a lot of time explaining to customers and partners why it’s better, and even then there’s a high likelihood that the specific benefit you’ve built is tangential to them (because each of these 2x improvements probably only applies to a subset of specific customers, and you likely only launch with one). As such, they have to try it to believe it, and even when they do, it does not result in a step function/order of magnitude improvement.

At scale though, the aggregation of multiple 2x benefits does compound. I think this is because each 2x benefit attracts different niches, or enables you to win smaller channels that competitors don’t focus on, with a more modest promise.

Obviously, Cash App was able to bundle enough of these 2x benefits together to start seeing compounding returns and reach the significant scale that it has today (this was aided by the inherent virality of P2P payments and Cash App’s loose approach to fraud and AML).

My question is this – what happens to all the B2C fintech companies that build differentiated 2x benefits but fail to bundle enough of them together to reach escape velocity?

Put differently, what happens to the folks who end up building planes rather than rocket ships?

Fintech’s mania period – roughly 2019 to 2022 – put a lot of money into the hands of smart, creative entrepreneurs, so this is a very important and timely question.

I don’t want those planes to crash!

What Do You Do When Your B2C Engine Starts to Sputter?

What do you do, as a B2C fintech founder, when you realize you won’t be able to continue scaling up your business?

One option is to pivot into fintech infrastructure.

Traditionally, to get anywhere meaningful in fintech, you had to solve at least 1-2 difficult technology problems. If you can package up that technology (and the associated IP) into a SaaS product that would be useful for other B2C financial services providers, you can become an infrastructure provider. The sales cycles are long (especially when selling to banks), but it’s generally more pleasant than waging CAC war in the B2C trenches.

This is the path that Astra (which started as a B2C financial automation app before branching off to create a payments platform) and Knot (which grew out of a neobank called Millions) took, among many others.

Another option is to get acquired.

Sometimes the acquirer is a bank (as with Fifth Third acquiring Provide). Sometimes the acquirer is a fintech company (Robinhood acquiring X1 is a recent example). Sometimes the acquisition makes strategic sense (I liked the idea of Rocket acquiring Truebill, even though the execution hasn’t been perfect). Sometimes the acquisition is baffling (I still don’t get JG Wentworth acquiring Stilt). And sometimes the acquisition is an ill-fated idea that ends in disaster (JPMorgan Chase acquiring Frank for its list of customers that allegedly turned out to be fake is an all-timer).

Another option, unfortunately, is to shut down.

Braid (multiplayer finance) and Daylight (a neobank for LGBTQ consumers) are two fairly recent examples of B2C fintech shutdowns that bummed me out.

A final option is to “partner” with banks.

I intentionally put “partner” in quotes because partnering with banks is a tricky and highly nuanced endeavor worth taking a closer look at.

Why Do Banks Partner with B2C Fintech Companies?

To understand what banks hope to get from partnering with B2C fintech companies, it’s useful to first understand the shortcomings of other bank–fintech engagement models.

As I’ve discussed many times in the newsletter, BaaS can be a highly efficient and scalable way for banks to generate revenue. However, compared to their fintech programs, the overall portion of revenue captured by banks in BaaS is not huge. This makes sense (the fintechs deliver most of the customer value), but it’s not ideal for the bank. Nor is the fact that the bank doesn’t have a direct relationship with the end consumers or that the fintech companies don’t think of their BaaS banks as partners, but rather as interchangeable vendors.

Acquiring a fintech company allows a bank to capture 100% of the upside, but it’s expensive (the way banks value themselves is significantly different than how VC-backed tech companies value themselves), risky (ask Chase if it would like a do-over on Frank), and difficult to make work over the long-term (big companies tend to wreck the culture of the smaller companies they acquire, which drives the acquired talent away).

Buying technology from fintech infrastructure providers can make the bank buyer feel more innovative (and the tech itself is often quite good), but, by itself, modern technology can’t transform a bank into a fintech company.

And that’s the core point – the reason that many banks want to partner with, acquire, or buy technology from fintech companies is because (and they would never admit this) they want to be fintech companies.

They want differentiation.

BaaS can’t deliver that. Fintech infrastructure can’t deliver that. Acquiring a fintech company (likely) won’t deliver that.

The alchemy of B2C fintech is the combination of technology, marketing, and customer-centric product design.

That’s what banks want to buy. And there’s no reliable and cost-effective way for them to do that today.

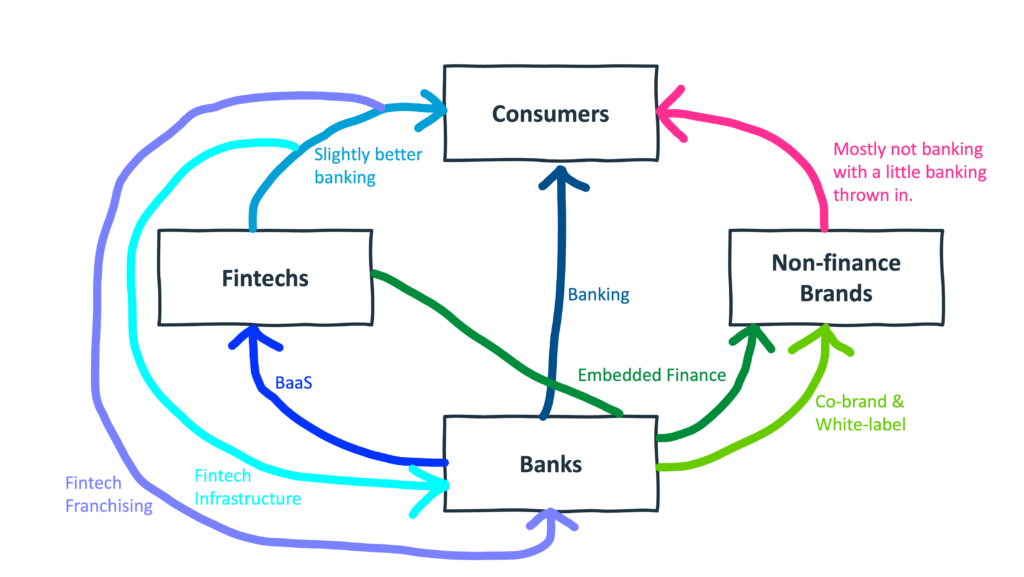

It feels like we need a different model – fintech franchises.

Fintech Franchises

According to my Workweek colleague – The Wolf of Franchises – a franchise is, essentially, a business-as-a-service.

You take everything that you’ve learned building and running a successful small business, and you package that knowledge into an operational, technological, and brand playbook, which you sell to someone else while retaining an economic stake in the franchisee businesses.

Typically, franchisees will pay the franchisor an upfront fee to access the playbook and then an ongoing revenue share (usually around 6%).

Now, given that most franchise businesses are brick-and-mortar stores, restaurants, or service businesses, we obviously wouldn’t want to port over this exact model to financial services.

For example, one of the big value propositions of buying into a franchise is the ability to share in that franchise’s brand. This works if the different franchisees are geographically distributed and unable to compete with each other. Financial services is mostly distributed digitally these days, which means that having different franchisees sharing the same brand and competing directly against each other online might not make as much sense.

Having said that, I think parts of the franchise model could make a lot of sense in B2C financial services.

Imagine being able to package up the technology, product design, user interfaces, and (genericized) marketing of successful niche B2C fintech products and franchise them out to banks (particularly community banks) to sell to their customers.

Imagine being able to flip the economics – basically the reverse of BaaS – with the bank retaining most of the revenue (and avoiding the expense and headache of acquiring the fintech company whole hog), but with the fintech company being paid a recurring revenue stream.

Imagine banks pooling their money, in much the same way that they do for bank-funded VC investing (through firms like Canapi Ventures and Alloy Labs), to pursue a private equity-like strategy of rolling up all these subtly differentiated B2C fintech companies and franchising their products back to the banks.

Sounds a bit outlandish, I know.

But it’s already kinda starting to happen.

In 2020, Greenlight partnered with Chase to launch a bank account for kids. Since then, it has partnered with a digital banking provider to resell its “Greenlight for Banks” offering and formed its own Credit Union Servicing Organization (CUSO) and taken investment from Curql (a VC firm funded by credit unions) to resell its product to credit unions.

Carefull – a financial protection platform for seniors – raised $16.5 million to help it expand its B2C offering into a co-branded B2B2C offering for banks and credit unions. As of October, more than 35 customer institutions and partners were already signed up.

HMBradley, which had built a highly opinionated and compelling take on the standard neobank product package – called it quits on B2C last year and raised $13 million to pivot into B2B2C. It’s unclear to me if this pivot will be more infrastructure-focused or product-focused, but I hope it’s the latter. Banks don’t need another digital banking provider or next-gen core. They need differentiated product thinking.

Perhaps the closest example of this fintech franchises model in the market today is Nymbus, which spun up a division to help community banks and credit unions incubate and launch niche digital banking brands. A recent example is Roger – a digital bank for military service members – was launched by Citizens Bank of Edmond (in partnership with Nymbus), and may eventually be franchised out by Citizens to other banks looking to better serve new military recruits in their communities.

Let’s Make This a Thing!

Unicorns are boring. Let’s figure out how to preserve the subtle differentiation that fintech founders have diligently built over the last five years and empower banks to better serve their customers.

Fintech franchises!