Imagine that you learned how to play chess at a young age and became good at it — like obsessively good. And you never really bothered to wonder why there was that empty space on the board, right next to the king. It was always just there.

Then you hear about a different version of chess — an older version — one in which that empty space next to the king was occupied by an unusually flexible and powerful piece — the queen.

How would you react?

Obviously, you’d be intrigued. A piece that can move in a straight line, in any direction, an unlimited number of spaces? Yeah, you’d be intrigued.

However, you might also be a bit hesitant. After all, you’ve spent your entire life mastering a game without the benefit of the queen. You’ve gotten good! Integrating the queen into your playstyle and strategy would be a huge disruption to your routine. It would be a temporary step backward.

This is an apt analogy for the current state of consumer lending.

We have a new piece that is unusually flexible and powerful: consumer-permissioned alternative data. If broadly adopted, it has the potential to significantly improve the game.

And yet, according to a survey of 125 decision-makers at banks, credit unions, fintechs, and other lending institutions, conducted by Nova Credit, only 43% of respondents said that they are using alternative data to improve their credit underwriting, despite 90% of respondents saying that they believed that such data would help them approve more worthy borrowers.

90% of players believe the queen would be useful, but less than half that amount are choosing to use it. That’s odd!

Let’s try to figure out why that is.

Why Did Alternative Data Become Alternative?

We should start by defining alternative data.

Alternative data is data about a consumer’s finances that isn’t captured in a traditional credit file.

Bank transaction data, employment and payroll data, and rent and utility payment data are all common types of alternative data.

This isn’t groundbreaking. It’s obvious. Alternative data is, for the most part, the type of data that you would write down on a whiteboard if you were asked to brainstorm a list of data sources that you think would be most helpful in predicting a consumer’s probability of defaulting on a loan.

In fact, banks used a lot of this data—particularly bank transaction and employment data—heavily in their consumer loan underwriting processes for much of the 20th century.

So, what changed? Why did alternative data become alternative?

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Put simply, it was an accident of history.

For most of U.S. history, consumer lending was an activity done more by merchants than by banks. Merchants wanted to enable their customers to buy more of their products and services, which meant offering them credit. However, unlike banks, merchants had no window into the broader financial lives of their customers. No insight into a customer’s income or employment or financial habits. They were lending blindly, which was, obviously, a very risky thing to do.

So they started sharing data with each other. Specifically, they started sharing loan repayment data with each other (which was the only data that they had).

These were the first credit bureaus.

They started locally (often as non-profits), but they eventually grew and consolidated into the large public companies that we know today.

A lot changed during those years – 1960 to 1990, roughly – including the displacement of merchants by banks as the dominant consumer lenders in the U.S. and the transition from paper-based credit files to digital ones stored in computer databases.

But one thing didn’t change – the data.

The credit bureaus were designed to efficiently collect and organize consumer loan repayment data. That was the central goal around which they were organized, and around which their technology was architected. And even though banks, unlike merchants, could have furnished a great deal more data to the credit bureaus – data that would have given lenders a more comprehensive view into consumers’ financial lives – they didn’t. They weren’t asked to.

Instead, credit files evolved into the tool that we are familiar with today — a narrow but very deep repository of consumer loan repayment data. This data has a lot of value for predicting the probability of default, and lenders and analytic companies like FICO have spent the last 60 years wringing every last drop of predictive value out of it.

This is why I find alternative data so exciting – it’s a (comparatively) untapped resource!

The Value of Alternative Data

The danger, when talking about alternative data, especially if you aren’t a data scientist (as I most definitely am not), is that the discussion can get a little handwavy. Alternative data is valuable because … data is the new oil, and AI will revolutionize the way that we understand and serve customers! Blah, blah, blah.

Let’s try to be much more precise.

What value does alternative data offer in a world that already has credit files and the FICO Score?

There’s an obvious answer and a more nuanced answer.

Let’s start with the obvious – alternative data can help lenders safely approve prospective borrowers who can’t be approved using only traditional credit data.

This population, which is made up of many sub-groups, including young consumers, recent immigrants, unbanked consumers, and consumers with damaged credit profiles, stands at roughly 100 million in the U.S.

At the risk of stating the obvious, that’s a big number – about a third of all Americans.

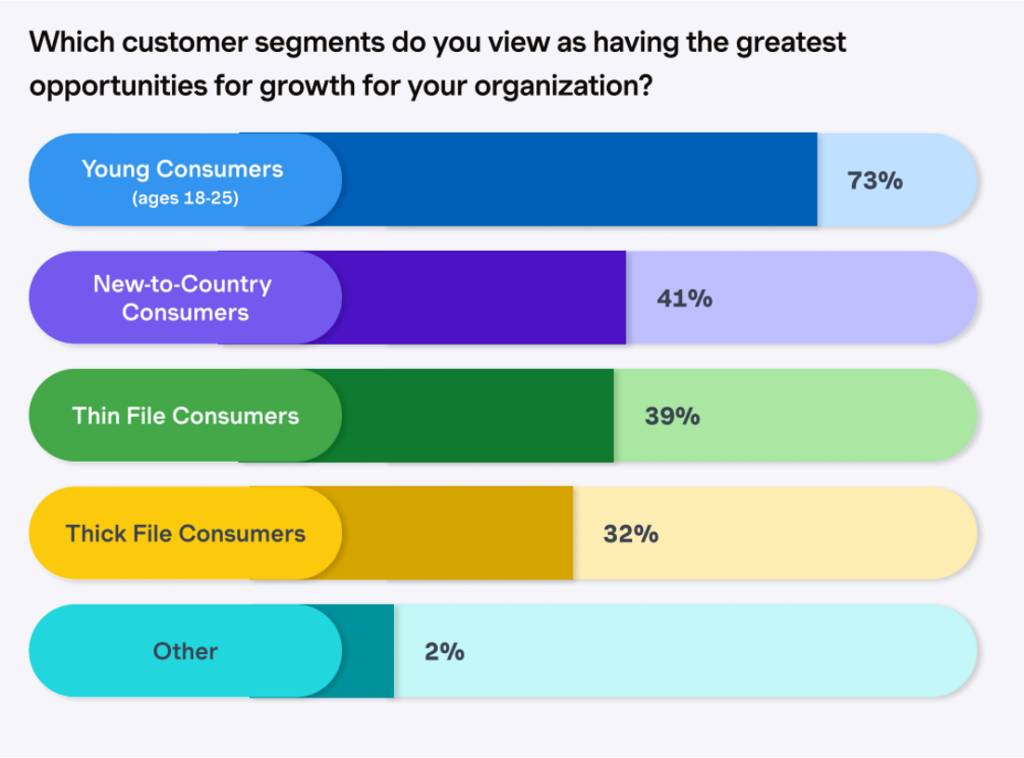

And it’s an opportunity for lenders that are looking to grow, which the Nova Credit survey confirmed when it asked respondents, “Which customer segments do you view as having the greatest opportunities for growth for your organization?”

This use case – filling in the gaps around traditional credit data – is where most of the traction for alternative data has happened, to date.

There is, however, a larger (and underexplored) opportunity – alternative data can help lenders make more accurate risk-based pricing decisions on all prospective borrowers.

How exactly can it do this?

Allow me to explain.

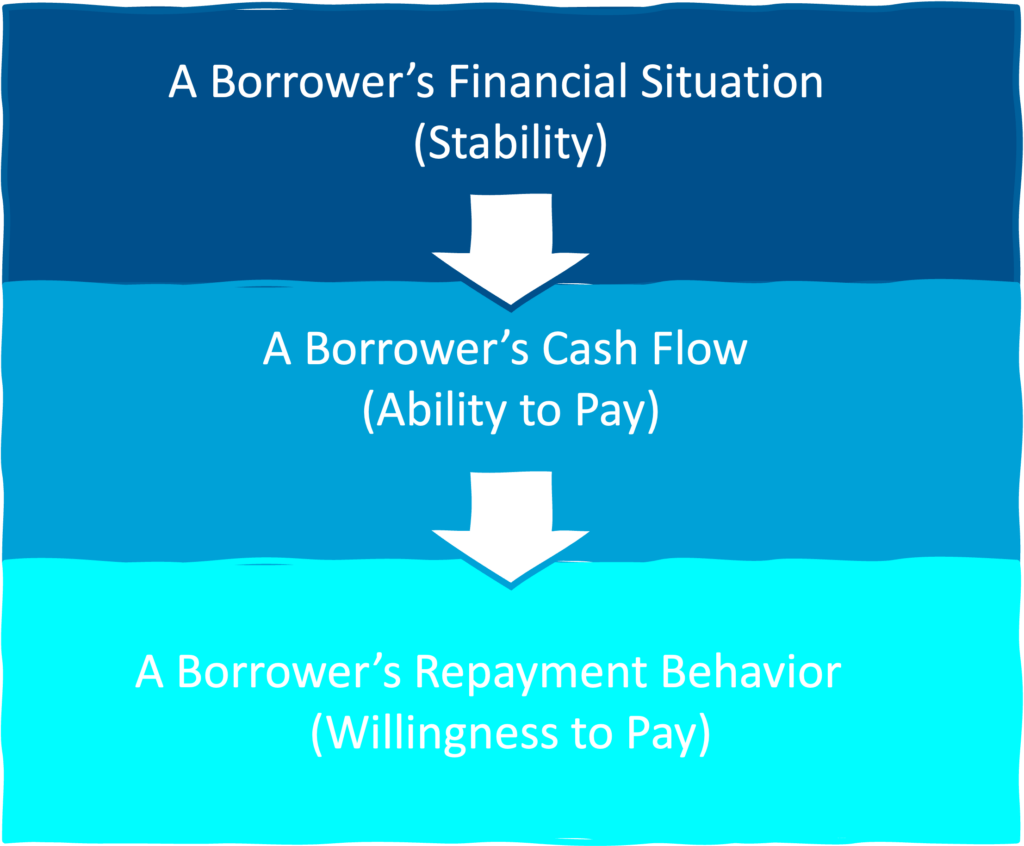

Not all data is equally and independently useful in making credit decisions. There is a hierarchy of insights that lenders are looking to glean from the data that they evaluate in the loan origination process. That hierarchy looks like this:

A borrower’s financial situation, which can be assessed by looking at things like their education, employment, where they live, and what, if any, non-liquid assets they might have, is an indicator of stability.

A borrower’s cash flow, which can be assessed by looking at the pattern of money flowing into and out of their bank accounts, is an indicator of their ability to pay.

A borrower’s repayment behavior, which is traditionally assessed by looking at repayment history, is an indicator of their willingness to pay.

What’s interesting is that each level in this hierarchy is somewhat dependent on the level above it.

For example, a consumer can be very diligent in managing their cash flow and ensuring that they don’t overspend, but the conditions under which they make those decisions are largely a function of their overall financial situation (how much money they make, their cost of living, etc.)

A similar interdependency exists between cash flow and repayment behavior. Different consumers react differently when they are under financial stress and juggling their payment obligations, but the conditions that create financial stress, that put consumers in the difficult position of having to decide which loans to pay back, are mostly a function of their cash flow (and overall financial situations). That’s why the term ‘willingness to pay’ is a bit misleading. After you screen out first-party fraud (consumers who apply with no intention of repaying the loan), all your remaining applicants are, in theory, willing to pay you back. That’s their intention. The challenge is in discerning which ones have put themselves in the position to be able to live up to that intention.

This is a useful framework for considering how different types of data deliver, directly or indirectly, the insights that lenders seek.

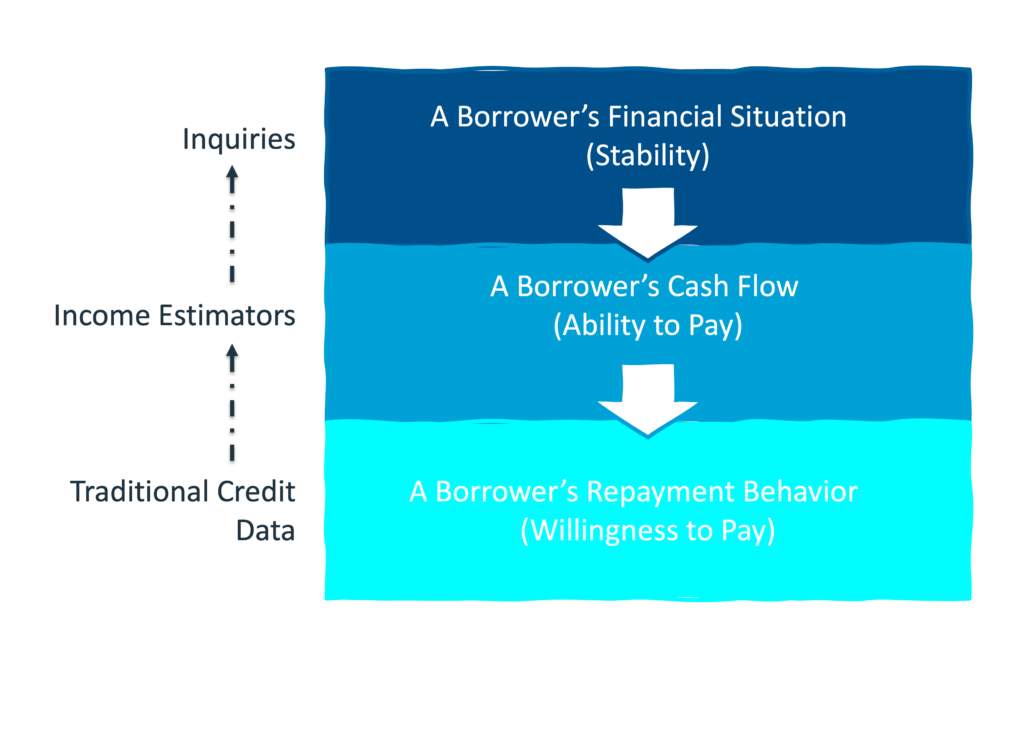

Traditional credit data is an excellent tool for directly understanding how consumers manage their loan repayment obligations. However, because financial behaviors are interdependent, it is possible (though not ideal) to use traditional credit data to infer insights into a consumer’s cash flow (as the credit bureaus did when they tried to get credit card issuers to use their income estimator models after the CARD Act was passed in 2009) and overall financial situation (inquires, on credit reports, serve as a lagging indicator of financial instability).

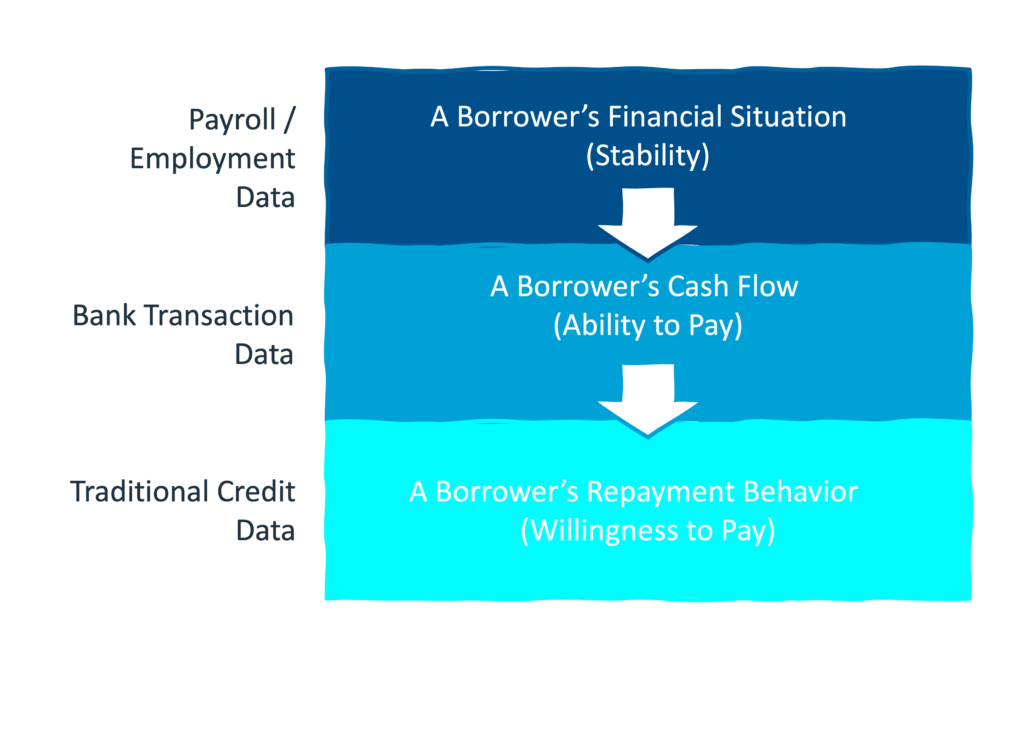

The value of alternative data, broadly speaking, is that it can be used to directly supply the insights that lenders need, rather than relying on the out-of-date and less-than-perfectly-accurate inferences made using traditional credit data.

Alternative data is deeply complementary to traditional credit data, not just for decisioning prospective borrowers on the fringes, but for making more accurate credit decisions for all applicants.

How Do We Unlock Access to Alternative Data?

Ok, so alternative data has value. Great.

The next problem is that, unlike the 1960s, companies today understand exactly how valuable their first-party data is. They don’t like to share it, especially not with for-profit companies that are trying to sell it back to them. This is a major challenge for the credit bureaus. How do you convince merchants, BNPL providers, property management companies, payroll companies, and banks to hand over their data (or, in the case of banks, more of their data) for free?

It’s tough.

Fortunately, we have a solution – consumer permission!

Consumer-permissioned data access, often referred to as open banking, has opened up the world of alternative data at a truly unprecedented level. The essential idea is that, in the same way that companies are free (with some restrictions) to leverage their first-party customer data, their customers are free (with some restrictions) to share their own data with any third parties that they authorize.

And the good news today (versus 20 years ago when consumer-permissioned data access first started to get traction via screen scraping) is that consumer advocates and regulators are passionate supporters of open banking generally, and cash flow underwriting specifically. Here’s CFPB Director Rohit Chopra, whose agency is finalizing rules to solidify open banking in the U.S., talking about the benefits for borrowers with no credit files or damaged credit profiles:

Bringing in your personal financial ledger to a new provider will let them consider your full financial history when offering you a loan, instead of relying on a summary from the credit reporting conglomerates. This means that individuals without years and years of credit history or those who may have had stumbles in the past can now be evaluated based on their current income and expenses.

So, to sum up, we know that alternative data is broadly useful to lenders, for both filling in the gaps around traditional credit data and layering new and valuable insights on top of traditional credit data, and we now have a well-established and regulatorily-blessed mechanism for accessing much of that data programmatically.

This brings us back to our question — why is it that, according to Nova Credit’s survey, only 43% of respondents said that they are using alternative data to improve their credit underwriting, despite 90% of respondents saying that they believed that such data would help them approve more worthy borrowers?

Implementation Challenges

The simple answer is that consumer-permissioned alternative data is, for most lenders, a net-new capability. And adding a net-new capability into an existing loan origination process is a multi-dimensional problem.

What do I mean by a multi-dimensional problem?

It’s like that bet that some bartenders will make with you on a slow night – they bet you that they will be able to balance a cup of water on top of three beer bottles, spaced equally far apart from each other, using only three butter knives, all of which are shorter than the distance between the beer bottles.

It’s a good trick because the solution isn’t obvious. The knives aren’t long enough to bridge between the bottles, and even if they were, the water glass is too big to balance on top of the resulting bridge.

The solution is to carefully weave the butter knives together, such that the tension in each knife is supporting the other two knives simultaneously. This creates a balanced point in the center of the bottles for the water glass to rest on.

The loan origination process is similar — a very carefully structured and tenuous compromise between different parties that could collapse at any moment.

You have the credit risk team, whose performance is evaluated according to the portfolio’s loss rate and, consequently, always interested in adding another data source to the origination process if it will provide an incremental lift (no matter how slight).

You have the compliance team, which is evaluated based on how effectively it minimizes regulatory risk for the institution and is thus never wild about adding in a novel and potentially risky source of consumer data.

You have the marketing team, which is evaluated based on the number of new customers added to the portfolio and is therefore always pushing for an origination process that says ‘yes’ to as many applicants as possible.

And you have the digital team, which is evaluated based on the conversion rate of the digital account opening process and is, as a result, very focused on keeping the applicant experience as smooth and friction-free as possible.

Balancing these competing interests is incredibly difficult, so you can imagine how pitching these teams an innovative new capability like consumer-permissioned alternative data can cause some consternation.

Consumer-permissioned alternative data helps the credit risk team make better risk decisions. Yay! → But wait! Those better decisions are leading to a lower approval rate, which is bad for the marketing team! Ohh no! → OK, phew! We adjusted our approach so that we’re keeping our loss rate steady while increasing the overall number of approvals. The marketing team is happy! → Ohh, shoot! Asking the applicant to log in to their bank account at the beginning of the process introduced a whole bunch of friction into the experience, and our conversion rate is plummeting, and the digital team is pissed! And ohh yeah, it turns out the compliance team has some FCRA-inspired concerns about reason codes and adverse action letters. Blast!

This drama is why a lot of the lenders that do use consumer-permissioned alternative data in their origination processes do so exclusively as a second look – a last-step intervention for applicants who weren’t able to be approved through the standard origination process.

This compromise is understandable, but far from optimal. Consumer-permissioned alternative data has too much value to be shunted off to the corners of the origination process.

As an industry, we need to find a way to overcome these implementation challenges. We have to work the queen into our chess game.

How do we do that?

I have a few suggestions.

Fully Embracing Consumer-Permissioned Alternative Data

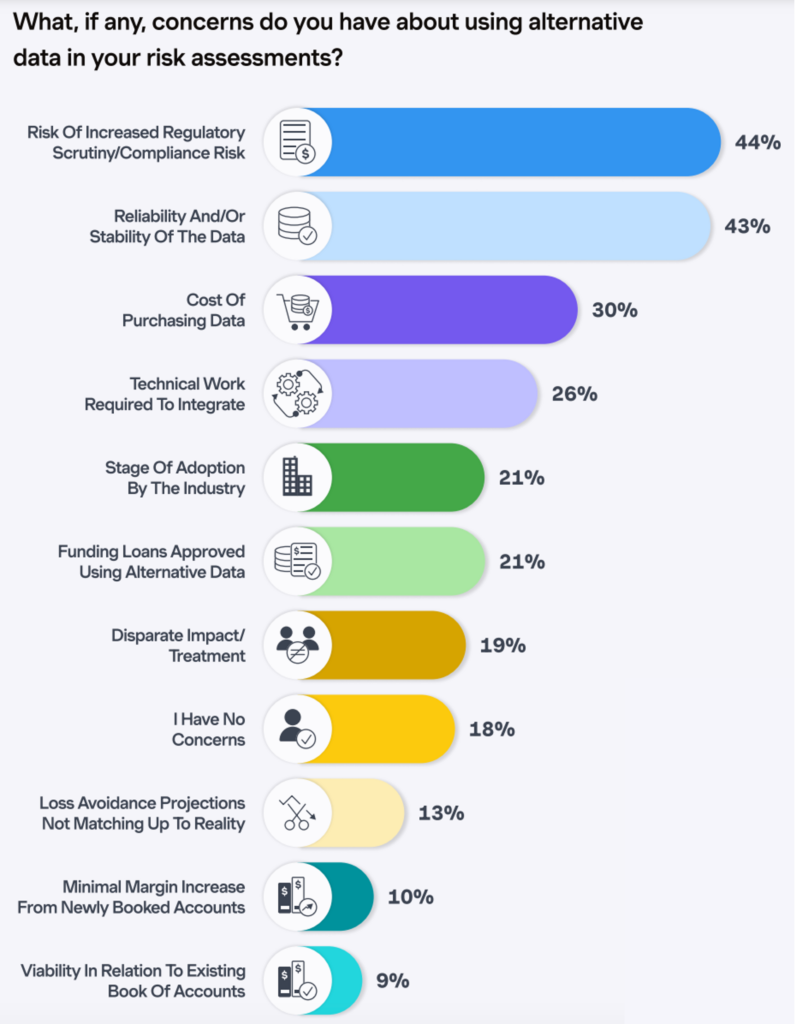

In its survey, Nova Credit asked lenders, “What, if any, concerns do you have about using alternative data in your risk assessments?”

Here’s what the respondents said:

I want to quickly discuss a few of these concerns and how lenders should start to consider addressing them.

Concern: Reliability and/or Stability of the Data

Answer: This concern comes up frequently in open banking. Despite the progress we’ve made in enabling consumer-permissioned data sharing, the experience is still far from perfect. Data aggregators don’t have comprehensive data coverage, and the continued use of screen scraping has a negative effect on latency and uptime.

In the short term, the best strategy for lenders to address this concern is to focus on redundancy. In the same way that lenders don’t rely on a single credit bureau, they should also consider building or buying data access infrastructure that allows for redundancy and least-cost routing across multiple data aggregators.

In the long term, the hope is that the CFPB’s rule on open banking will solve many of these coverage, latency, and uptime issues, although it should be noted that in other countries, this hasn’t proven to be a sure thing.

Concern: Technical Work Required to Integrate

Answer: Consumer-permissioned alternative data, particularly bank transaction data, is messy. It’s just messy enough, in fact, that it is extremely difficult for data scientists to work with in its raw form.

It’s important for lenders to make data cleansing and standardization a priority in any investment in consumer-permissioned alternative data.

Concern: Loss Avoidance Projections Not Matching Up to Reality & Minimal Margin Increase From Newly Booked Accounts

Answer: I was not surprised that this was a smaller concern for most respondents. Generally speaking, when credit risk professionals get their hands on consumer-permissioned alternative data, they come away with the conviction that it can provide a significant lift.

Having said that, it’s not always obvious how to extract analytic value from this data. Analytics is both an art and a science. The art is in understanding the problem you’re trying to solve and the data you’re using well enough so that you can develop useful intuitions about how to design your model.

Many lenders lack that specific expertise with consumer-permissioned alternative data, which makes it imperative to find partners, vendors, or consultants who can help them understand, analyze, and operationalize this data, at scale.

Concern: Risk of Increased Regulatory Scrutiny/Compliance Risk & Disparate Impact/Treatment

Answer: Compliance is always lenders’ biggest concern when incorporating alternative data into the loan origination process.

To be honest, there isn’t an easy answer. Compliance risk in financial services can’t be mitigated by a silver bullet. My only recommendation is to work with partners, vendors, and consultants that have the specific (and very rare) experience of applying the Fair Credit Reporting Act (and other applicable lending regulations) to consumer-permissioned data. The deeper their experience, the better. You want to work with providers that have dealt with everything – fair lending and disparate impact, model risk management and governance, adverse action notices and reason codes – and that have policies and procedures that have been battle-tested by the biggest banks and non-bank lenders.

A First-Mover Advantage

There’s one last concern from the Nova Credit survey that I want to talk about – Stage of Adoption by the Industry.

That’s a bit vague, so allow me to translate – We don’t want to stick our neck out. We want to be second, not first.

This attitude is not uncommon among lenders, especially banks. And it’s not always a bad strategy. Being too early to a trend in financial services can be just as damaging to a company’s business as being too late.

However, in this particular case, I think waiting on your peers is a mistake.

Not since the late 1980s – when we saw the emergence of three national credit bureaus and the launch of the general-purpose FICO Score – have lenders in the U.S. had the kind of greenfield opportunity to creatively apply new sources of data to loan origination process that they do today, thanks to the emergence of consumer-permissioned alternative data.

There is a massive first-mover advantage to be gained here. One that only comes along once in a generation.

And if that statement feels a bit hyperbolic, consider the outcome of the lender that seized that advantage last time – Capital One.

Capital One was created when Signet Financial Corp spun off its wildly profitable credit card business into a monoline company in 1994. The cause of the credit card unit’s success – an obsessive focus on data-driven experimentation – was also what caused it to be spun off, according to an early Capital One employee (as recounted in the book It’s Alive: The Coming Convergence of Information, Biology, and Business):

The highly analytic, scientific culture of that division became more and more at odds with the banking culture of Signet, to the point where Signet ejected the group because of all the chaos and friction it created.

Capital One’s data-driven experimentation was fueled by an intense focus on trying to understand its customers, to understand them better than perhaps any financial services company had ever understood its customers. A young Capital One executive named Frank Rotman elaborates:

You start to think about customers as customers, not as data sitting in a computer. A customer who charged off and didn’t pay us off is a real person with a real situation. And by listening to them explain their situation through their lens, hearing how they made decisions about paying their bills, maybe even by looking at the data about their transactions, we can learn. These individual data points could lead to insight.

Consumer-permissioned alternative data provides lenders with an immense opportunity to learn about their customers.

The question is, which lender will seize that opportunity?

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Nova Credit.

The Nova Credit platform gives lenders the power to underwrite anyone. For years, Nova has empowered lenders to better see the credit invisible and extend credit safely. To date, Nova Credit has helped partners unlock well over $10B in credit for their customers through our Cash Atlas™, Income Navigator, and Credit Passport® products. Lending institutions can use Nova Credit Platform to grow responsibly by streamlining onboarding, verification, and underwriting processes of alternative data with a unified integration.

If you are interested in staying ahead of where cash flow is headed, be sure to apply to attend the inaugural Cash Flow Underwriting Summit in NYC on September 12th, presented by Nova Credit.