Let’s start with a couple of recent news stories.

The first is the story of a man named Romeo Chicco.

At the end of last year, Mr. Chicco attempted, unsuccessfully, to get auto insurance from seven different providers. When he finally succeeded on the eighth attempt, he ended up paying nearly double the price that he had been paying previously.

Why?

Well, after some investigating, he discovered that it was due to a negative report from LexisNexis, the data broker and consumer reporting agency (CRA), which had assembled some rather interesting data on his driving habits:

When Mr. Chicco requested his LexisNexis file, it contained details about 258 trips he had taken in his Cadillac over the past six months. His file included the distance he had driven, when the trips started and ended, and an accounting of any speeding and hard braking or accelerating. The data had been provided by General Motors — the manufacturer of his Cadillac.

Why did G.M. share this data with LexisNexis? GOOD QUESTION!

In his complaint, Mr. Chicco said he called G.M. and LexisNexis repeatedly to ask why his data had been collected without his consent. He was eventually told that his data had been sent via OnStar — G.M.’s connected services company, which is also named in the suit — and that he had enrolled in OnStar’s Smart Driver program, a feature for getting driver feedback and digital badges for good driving.

Mr. Chicco said that he had not signed up for OnStar or Smart Driver, though he had downloaded MyCadillac, an app from General Motors, for his car.

A spokeswoman for G.M., Malorie Lucich, previously said that customers enrolled for SmartDriver in their connected car app or at the dealership, and that a clause in the OnStar privacy statement explained that their data could be shared with “third parties.” Asked about the lawsuit, she said by email that the company was “reviewing the complaint,” and had no comment, pointing instead to a statement the company previously gave about OnStar Smart Driver.

So, essentially, Mr. Chicco checked a box while downloading G.M.’s mobile app, and that authorized G.M. to share (i.e. sell) data on his driving behavior to LexisNexis, which was then resold in the form of an insurance risk report and score to the insurance companies that were evaluating Mr. Chicco.

Our second story is about JPMorgan Chase.

While it’s difficult to feel the same level of sympathy for the country’s largest bank as we do for Mr. Chicco, JPMC recently discovered that it, too, had been wronged by a data broker:

JPMorgan Chase has sued TransUnion for what it calls an “elaborate, decade-long scheme” by Argus, a unit of TransUnion, to “secretly misappropriate JPM’s valuable trade secret data.” The “trade secret data” the bank refers to is anonymized credit card data.

In the lawsuit the New York bank filed against Chicago-based TransUnion last week in Delaware Federal District Court, it said Argus Information & Advisory Services collected the bank’s credit card data while under contract as a data aggregator for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Argus then, without permission and in violation of its contracts with those agencies, used that data in the benchmarking services it sells to other banks, according to the bank.

Whoops!

Sign up for Fintech Takes, your one-stop-shop for navigating the fintech universe.

Over 41,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

And despite TransUnion’s rather uninspiring defense that all this happened before it acquired Argus from Verisk (another data broker) in 2022, legal observers don’t like TU’s chances in the coming court case because Argus just settled a different case with the government on the same basic charges:

The bank’s case is bolstered by the fact that earlier this month, Argus agreed to pay $37 million to settle a civil investigation by the Department of Justice and other federal authorities accusing it of the same thing – using anonymized credit card data collected for government agencies in the benchmarking services it sells to credit card issuers, in violation of its government contracts.

The contracts each restricted Argus’ ability to use, disclose or distribute credit card data collected from banks for purposes other than the performance of the work under the government contracts.

But the company used this anonymized data to create synthetic data that it incorporated into the products and services it sold to some commercial customers, the DOJ said.

Whoops! Whoops! Whoops!

These stories are obviously bad, but the reason they’re important is that they (and many more like them) are motivating a specific financial services regulator to take some dramatic actions.

Enter: The CFPB

Rohit Chopra, Director of the CFPB, has been talking non-stop for the last couple of years about the huge potential for consumer harm coming from AI and its insatiable appetite for consumer data:

Today, “artificial intelligence” and other predictive decision-making increasingly relies on ingesting massive amounts of data about our daily lives. This creates financial incentives for even more data surveillance. This also has big implications when it comes to critical decisions, like whether or not we will be interviewed for a job or get approved for a bank account or loan. It’s critical that there’s some accountability when it comes to misuse or abuse of our private information and activities.

Left to the free market, Director Chopra fears that this demand for consumer data will be met by increasingly unscrupulous companies and business practices, which he lumps into the category of ‘data surveillance’:

While these firms go by many labels, many of them work to harvest data from multiple sources and then monetize individual data points or profiles about us, sometimes without our knowledge. These data points and profiles might be monetized by sharing them with other companies using AI to make predictions and decisions.

In many ways, these issues mirror debates from over fifty years ago. In 1969, Congress investigated the then-emerging data surveillance industry. The public discovered the alarming growth of an industry that maintained profiles on millions of Americans, mining information on people’s financial status and bill paying records, along with information about people’s habits and lifestyles, with virtually no oversight.

Of course, today’s surveillance firms have modern technology to build even more complex profiles about our searches, our clicks, our payments, and our locations. These detailed dossiers can be exploited by scammers, marketers, and anyone else willing to pay.

Those statements are difficult to deny – remember, Mr. Chicco’s car was essentially spying on him in order to profit G.M. – but the question is what, specifically, is Director Chopra going to do about it?

Open Banking and the FCRA

There are two big initiatives underway at the CFPB, which, taken together, have the potential to dramatically reshape the financial services data economy.

The first is open banking.

I have written a lot about the CFPB’s personal financial data rights rule, which it is working to finalize under the authority granted to it by Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act (check out this essay and this follow-up if you need a primer). I won’t rehash all the details here.

Suffice it to say that the CFPB is proposing a relatively narrow regulatory framework in order to advance a much larger and more comprehensive philosophical idea – financial data that is generated by or associated with a consumer is owned by the consumer and should only be shared with their explicit authorization and only for the narrow purpose for which it has been authorized.

You can easily see how this consumer-driven data-sharing philosophy conflicts with the General Motors and TransUnion stories I shared earlier.

Checking a box and agreeing to a densely written privacy policy that says that the company may share your data with unspecified third parties for unspecified reasons obviously falls well short of the general data privacy standard that the CFPB is trying to help set in the U.S. with its open banking rule.

The same is true in the case of JPMC and TU.

Does a company that is in possession of sensitive data have the right to anonymize that data or use it to create synthetic data without the explicit permission of the owners of that data?

If you squint your eyes and tilt your head just so, you can maybe see how someone (like the folks working at Argus) could reasonably believe that the answer is ‘yes’. After all, who’s getting hurt? The data is being anonymized or otherwise transformed in such a way that there is no risk of a data breach or negative outcome for an individual consumer. What’s the problem?

The problem is that it’s not their data!

In this specific case, Argus’s contracts with the government specifically forbade them from any secondary uses of the data that they were collecting from JPMC and the other big banks. But even if they hadn’t, it’s still not Argus’s data! They can’t just do with it whatever they please! That’s the general line in the sand that the CFPB is attempting to draw with 1033 – you are only allowed to use someone else’s data for the specific purpose they have authorized. Nothing else.

Now, of course, there’s quite a bit of consumer data that gets shared without consumers’ explicit authorization in the financial services industry today. And a lot of that data sharing is vitally important for ensuring that financial services providers can serve consumers in a safe, profitable, and legally compliant manner.

This is where the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) comes in.

The FCRA was enacted by Congress in 1970. It was one of the world’s first data privacy laws, and it was intended to give consumers more rights and control over the data that consumer reporting agencies (the legal term for credit bureaus) were assembling and selling. The FCRA allows for certain sanctioned uses of consumer report data (i.e. permissible purposes, such as making credit, insurance, or employment eligibility decisions) but strictly prohibits other uses of the data. Additionally, the FCRA mandates certain accuracy requirements and gives consumers a right to see their data, and due process rights to dispute inaccurate or incomplete information in their files.

The CFPB, which has rulemaking authority in regard to the FCRA, believes that the FCRA has, by virtue of being more than 50 years old, failed to keep pace with the data surveillance industry it was designed to constrain:

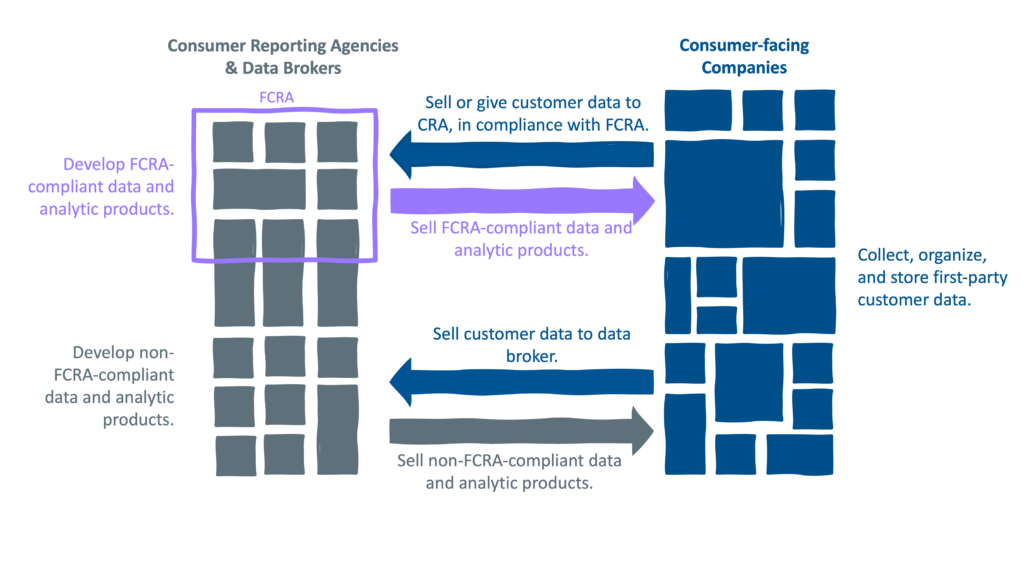

You have consumer-facing companies – banks and other financial services providers, as well as non-bank companies like G.M. – collecting data on their customers and either selling or furnishing that data for free to data brokers. Those data brokers – some of which are regulated under the FCRA as consumer reporting agencies and many which are not – are assembling and evaluating the data they collect, developing data products (e.g. credit files) and analytic products (e.g. credit scores), and selling them back to banks and non-banks for a variety of different purposes.

In much the same way that prudential regulators talk about the threat of shadow banking outside the regulatory perimeter, the CFPB sees the potential for massive consumer harm in the data surveillance industry that sits outside the boundaries of the FCRA.

The bureau is determined to rein that risk in, which is why it has initiated a formal rulemaking process around the FCRA. That process is not as far along as the rulemaking for 1033, but it is far enough along that we know the general shape of what the CFPB is planning to do. Here are the key points:

- Expanding the definition of consumer reporting agencies (CRAs). The CFPB wants to expand the perimeter of the FCRA as much as possible. This would include all data brokers that sell data that is used for an FCRA permissible purpose (credit, insurance, employment eligibility decisions), whether they know that their data is being used that way or not, as well as all data brokers that sell data that is typically used for FCRA permissible purposes.

- Restricting the sale of consumer data. The CFPB also wants to ensure that FCRA-covered data is only sold for a permissible purpose or when a consumer grants their explicit written permission. Non-risk use cases for the data, like marketing (which is big business for the credit bureaus and other data brokers today), would be restricted.

- Expanding the definition of “assembling or evaluating”. Historically, a loophole has existed in the FCRA, which allowed companies to transmit consumer data for permissible purposes without being considered a CRA as long as they didn’t “assemble or evaluate” the data (i.e. creating files, attributes, scores, etc.) The CFPB is contemplating closing this loophole, which would be a big change for the open banking data access platforms, among others (this was likely a motivating factor for Plaid to become a CRA last year).

- Making credit header data FCRA data. Credit header data is the identity data at the top of the credit file (name, address, DOB, SSN), which the credit bureaus have built a very robust business around for supporting non-FCRA use cases, such as marketing and fraud prevention. The CFPB is considering restricting the use of credit header data to only permissible purpose use cases, which would be a big (and unpopular) change.

- Restricting data aggregation and anonymization. As mentioned earlier, the CFPB generally doesn’t seem to believe that aggregating or otherwise anonymizing consumer data makes it OK for companies to use the data in ways that they were not explicitly authorized to. The bureau’s proposed rule may restrict or limit this type of secondary use.

- Limiting scope and giving consumers more control. Building on the prior point, the CFPB appears to be very focused on making sure that buyers of FCRA-covered data only use the data for the narrow permissible purpose for which they got it and that consumers are empowered to grant and revoke written authorization to use their data.

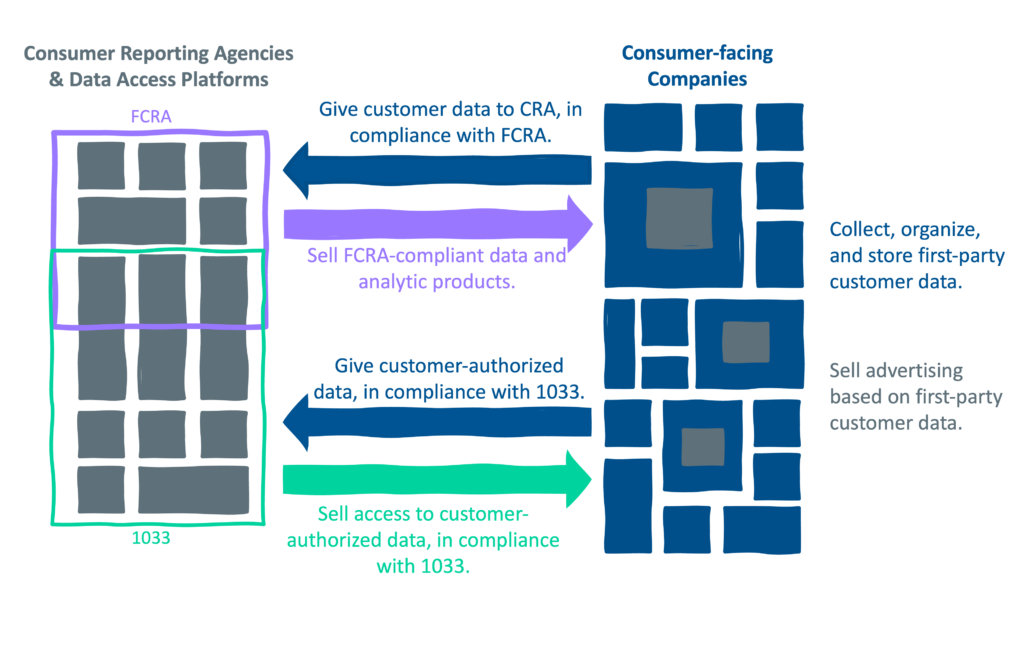

Taken all together, we can conclude from the CFPB’s rulemaking on the FCRA and Dodd-Frank Section 1033 that the bureau wants to dramatically reshape the financial services data economy into something that looks more like this:

A couple of notes:

- I think that in Director Chopra’s perfect world, he would like to see the traditional credit bureaus and data brokers completely subsumed within a consumer-permissioned data access framework (the green box). I don’t think he likes the idea of any consumer data being shared without consumers’ explicit permission. That said, there’s no way the traditional credit bureau model is going anywhere. It’s too entrenched, and candidly, there’s a value in collecting negative consumer data that consumers would never voluntarily share.

- Absent this perfect world, the CFPB seems intent on shoving as much of the data surveillance industry into the FCRA box as possible. One interesting side effect of this may be the slow elimination of consumer reporting agencies like LexisNexis buying data from sources that don’t also consume their data. These one-sided, for-profit arrangements can lead to a lot of harm for consumers with very little opportunity for redress (how does Mr. Chicco dispute the driving behavior data that G.M. provided?)

- The restriction of secondary use on both the open banking and FCRA sides of the fence is a big deal. The credit bureaus depend on secondary use provisions to develop many of the products that they sell (you can’t build attributes or predictive models without them). Unless the CFPB backs off a bit here (which may very well happen), they will essentially freeze the market for these products where it is today, which is bad for the credit bureaus and very bad for the open banking data access platforms (Plaid, MX, Finicity, etc.) that are trying to catch up to them.

- It will be interesting to watch how the CFPB manages the overlap between 1033 and the FCRA. Several of the big players in open banking (Nova Credit, Finicity, Plaid) have already become consumer reporting agencies. Will the combination of requirements under both regulatory frameworks place these providers at a disadvantage relative to traditional CRAs that don’t depend on consumer permission?

- You might have noticed in our picture that some of the gray data broker boxes appeared inside the blue consumer-facing companies. That, my friends, represents the rise of first-party data media networks. This trend, which is already manifesting in the financial industry (e.g. Chase’s new Media Solutions business), isn’t something that Director Chopra loves (I’m guessing), but it’s the inevitable consequence of expanded data privacy regulation of third-party data sharing. More financial services companies will follow Chase’s lead here.

Your Mileage Will Vary

It’s important to remember that this vision of the future is focused on what, in my opinion, the CFPB wants to see happen.

It’s highly unlikely, for reasons both legal and operational, that it will actually turn out that way.

This stuff is difficult to predict … but very fun to speculate on 🙂