If you were going to loan someone money and you wanted to predict if they were going to pay you back or not, what pieces of information would you most want to see?

This isn’t a trick question.

When I used to teach financial literacy to high school students, I’d ask them this question and they would usually give me the same two answers that you’re likely thinking of right now:

- The person’s history of borrowing money from other people.

- How much money they make.

These are the obvious answers, and, indeed, these two datasets, which cover willingness to pay and ability to pay, respectively, have been the twin pillars of loan underwriting for as long as companies have been lending money.

What’s interesting, however, is how little infrastructure has actually been built around that second pillar.

For the last 50+ years, lenders, credit bureaus, and analytics providers like FICO have spent a tremendous amount of time and money squeezing as much predictive value out of willingness-to-pay data (i.e., traditional credit data) as possible and next to nothing on ability-to-pay data (i.e., cash flow data).

Why?

It’s actually very simple – in the 1970s, credit data was much easier to deal with.

Credit data is straightforward. The structure is simple and relatively consistent across product types (loan amount, payment amount, balance, delinquencies, etc.). It doesn’t change frequently (because loan repayment cycles happen on a monthly basis), and there’s just not that much of it (because most people don’t borrow a lot of money over the course of their lives).

Cash flow data, by contrast, is tricky. While it can be summarized in simple terms (revenue, expenses, income), the actual inflows and outflows are made up of hundreds or thousands of distinct, real-time transactions a year. The data is constantly changing, and the sheer volume of data is much larger over the course of an individual’s life.

Asking a bank or a credit bureau in the 1970s which dataset they would prefer to build lending infrastructure around would have been like asking an automobile manufacturer in the 1910s which fuel source they’d prefer to build their car around – gasoline or electricity?

Gasoline was the obvious choice. It was cheap, abundant, and it has an incredible energy density (meaning that you can drive a lot of miles on a single tank). That’s why most of the cars being driven around today still run on gasoline.

Credit data was similar. It was cheap, easy to aggregate, and has an incredibly high predictive density (meaning that you can directly calculate or infer a great deal about a consumer’s financial situation from it). That’s why most credit decisions made today are still made using traditional credit data.

With the benefit of hindsight, these choices often appear to have been inevitable. However, in the moment, they are often much closer than we might appreciate.

In 1914, Henry Ford told the New York Times:

Within a year, I hope, we shall begin the manufacture of an electric automobile. I don’t like to talk about things which are a year ahead, but I am willing to tell you something of my plans.

The fact is that Mr. [Thomas] Edison and I have been working for some years on an electric automobile which would be cheap and practicable. Cars have been built for experimental purposes, and we are satisfied now that the way is clear to success. The problem so far has been to build a storage battery of light weight which would operate for long distances without recharging. Mr. Edison has been experimenting with such a battery for some time.

Larry Rosenberger, who joined FICO nearly 50 years ago and became CEO in 1991, two years after the launch of the general-purpose FICO Score, had a similar reflection on cash flow data:

Cash flow data is gold. The only reason it wasn’t used at the beginning of FICO is because it wasn’t widely available.

As technology improves, companies are presented with new opportunities to revisit past prioritization choices.

As battery technology has matured, Ford has dramatically reassessed its strategy on electric vehicles, investing roughly $12 billion in its EV business over the last decade.

More germane to the subject of this essay, as open banking has become more reliable and ubiquitous over the last couple of decades, lenders and lending infrastructure providers have begun to reassess the practicality of cash flow data for loan underwriting.

This is very exciting!

However, this burgeoning space can also be difficult to keep track of, especially as more companies jump into cash flow underwriting, each talking about their own products, use cases, and competitive differentiators.1

So, my goal for this essay is simple – to tell you everything you have ever wanted to know about cash flow underwriting but were afraid to ask.

Let’s start with the obvious first question.

What is cash flow underwriting?

I’ll try to provide a simple definition.

Cash flow underwriting is the use of cash flow data to evaluate and price the risk of credit default in a manner that is compliant with applicable laws and regulations.

A few notes on this definition:

- Cash flow data is generally defined as historical and current information about the money flowing into and out of an applicant’s transaction accounts (checking, savings, prepaid, etc.) This information can provide valuable signals, which can be used to predict risk.

- Traditionally, cash flow underwriting was done manually, with an applicant providing paper copies of their bank transaction data (they would literally bring in shoeboxes full of old bank statements) to a human underwriter at the bank who would personally review and analyze that data in order to make a decision. Traditional cash flow underwriting was obviously highly inefficient and expensive, which is why modern cash flow underwriting – where the data is accessed digitally (often through open banking) and analyzed using software – is so exciting.

- It’s important to ground our definition in compliance with applicable laws and regulations, such as those that govern consumer data privacy (like the Fair Credit Reporting Act) and fair lending (like the Equal Credit Opportunity Act). Cash flow underwriting is only valuable if it can fit within lenders’ existing compliance frameworks.

- Cash flow underwriting is a process that can be applied to both consumer lending (which is just catching on) and commercial lending (which is now fairly common). For the purposes of this essay, I’ll focus on consumer lending.

Why is cash flow underwriting such a hot topic right now?

Folks in the financial services ecosystem started getting excited about the concept of modern cash flow underwriting around 2016. This was when entrepreneurial enthusiasm for both online lending and building on top of the burgeoning open banking infrastructure in the U.S. really started to gain momentum.

This enthusiasm has been matched (or perhaps even slightly exceeded) by the enthusiasm that regulators and consumer advocates have shown for cash flow underwriting in the years since.

Here’s Rohit Chopra, Director of the CFPB, explaining how his agency’s work on the forthcoming open banking rule in the U.S. will empower borrowers with more choices:

Bringing in your personal financial ledger to a new provider will let them consider your full financial history when offering you a loan, instead of relying on a summary from the credit reporting conglomerates. This means that individuals without years and years of credit history or those who may have had stumbles in the past can now be evaluated based on their current income and expenses.

And here is Michael Hsu, Acting Comptroller of the Currency, providing an update on the progress of the OCC’s Project REACh (a collaborative industry initiative focused on increasing financial inclusion by expanding access to credit and capital):

As part of Project REACh, several national banks have undertaken a pilot program to use alternative, non-FICO data – primarily from deposit accounts – to qualify consumers for first time credit cards. As of October 31, 2023, over 110,000 accounts were established under this pilot. Participating banks have been monitoring key performance metrics to track customers’ credit progression after account opening.

In the same way that the EV market has exploded in recent years thanks to the combination of government subsidies (inspired by environmental concerns) and rapidly improving battery technology, cash flow underwriting is having a moment right now thanks to the combination of government support (inspired by accessibility and competition concerns) and rapidly improving open banking infrastructure.

How well does cash flow underwriting predict credit default risk?

This is always the sticking point when it comes to using new data sources in loan underwriting.

The concept can make perfect sense on the whiteboard, and regulators and consumer advocates can love it, but if it doesn’t help lenders make more accurate credit risk decisions, then it’s not going anywhere.

Lenders don’t like to take a data provider’s word for it. They want to see proof in the form of performance data (the credit bureaus and FICO obviously have decades’ worth of data on how traditional credit data performs).

Fortunately, Prism Data can help us here. Prism has a unique history as an analytics provider that was spun out of a consumer credit card company, which utilized cash flow data to underwrite credit-invisible, thin-file, and sub-prime consumers beginning in 2018. In recent years, Prism has amassed a large “consortium” of cash flow underwriting performance data — inclusive of many loan types and customer segments — that can be used to demonstrate just how effective modern cash flow underwriting is at rank-ordering the probability of default.2

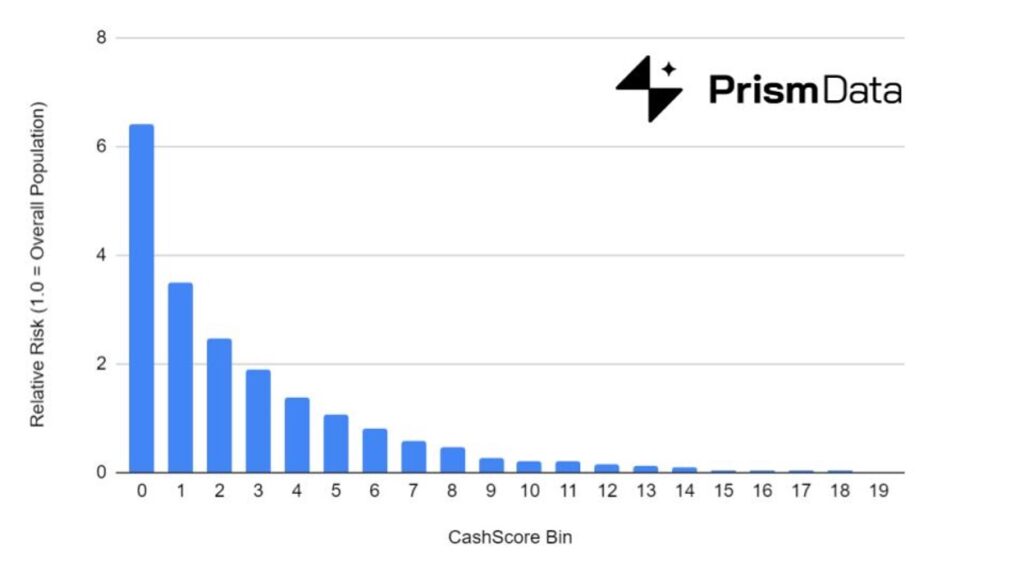

In the chart below, Prism separated borrowers into twenty equal groups – or bins – based on the strength of their cash flow underwriting assessment using Prism’s latest cash flow underwriting risk score (the CashScore®). As you can see, the cash flow assessment rank-orders risk consistently (i.e., borrowers in CashScore bin 3 are riskier than borrowers in CashScore bin 4, etc.). This analysis is completely independent of traditional credit scores or credit bureau data.

More interestingly, according to Prism’s analysis, the CashScore performs roughly as well as the FICO Score or VantageScore in terms of predicting credit default risk. Statistically, this is measured through metrics like the Area under the ROC Curve (AUC) or the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) Statistic. VantageScore and CashScore by Prism Data actually have the same AUC of 0.76.

OK, so if cash flow underwriting is equally effective as credit bureau data in rank-ordering risk, why do we need it? Where does it add value?

This is the billion-dollar question.

Cash flow underwriting adds value in two distinct ways, one obvious and one more subtle.

Let’s talk about the obvious way first – cash flow data allows lenders to safely underwrite consumers who lack traditional credit data.

According to the CFPB, there are roughly 26 million credit-invisible adults in the U.S. and another 10 million who lack sufficient credit data to be scorable using traditional models.3 The reasons for their unscorability vary. Some are young adults who are just entering the credit system, some are recent immigrants to the U.S., and some are older consumers who haven’t had any reason to use credit for decades.

Regardless, one thing that most of these consumers have in common is that they have transaction accounts. Thus, they are underwritable using cash flow data.

This credit-invisible population is a promising, low-risk customer acquisition opportunity for lenders.

Non-bank lenders have been attacking this space successfully for a while now. Prism shared with me that credit invisible consumers approved by one of its non-bank clients using CashScore exclusively went on to earn an average credit score of 682.

More recently, with regulators’ encouragement, banks have also been exploring this opportunity. Bank participants in the OCC’s Project REACh cash flow underwriting pilot report that, after 12 months, the average FICO Score of approved customers (who started out credit invisible) was 680.

However, the benefits are not limited to consumers who lack credit scores. Although credit scores and cash flow scores rank similarly in terms of overall predictive power, the risky borrowers they identify are different.

This brings us to the more subtle but no less important value add – cash flow data, when layered on top of traditional credit data, significantly improves lenders’ ability to predict and price credit default risk, across the credit risk spectrum.

Wait, WHAT?!?

I know! Pretty cool!

In data science speak, cash flow underwriting is orthogonal to traditional credit risk analysis. What that means is that cash flow data is, for the most part, picking up different signals than traditional credit data. In fact, according to Prism’s analysis of data from a variety of lenders who have provided them with both a traditional credit score and cash flow data to derive a CashScore, the statistical correlation between the two was only 0.22.

If you think about it, this makes intuitive sense.

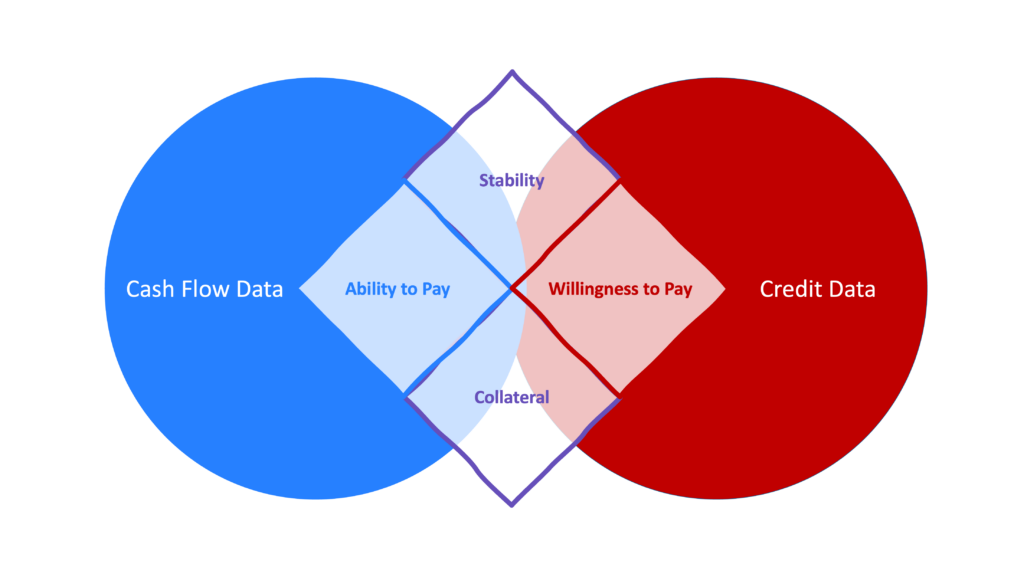

When you’re underwriting a loan, there are four essential things that you are looking at:

- Willingness to Pay – Does the consumer have a demonstrated history of responsibly entering into credit arrangements and managing the resulting payment obligations?

- Ability to Pay – Does the consumer have the financial means to meet their existing obligations and the capacity to take on new ones?

- Stability – Has the consumer’s financial situation been stable over time? How likely is it to change drastically in the future?

- Collateral – What is the value of any collateral that the consumer may use to offset the risk for the lender?

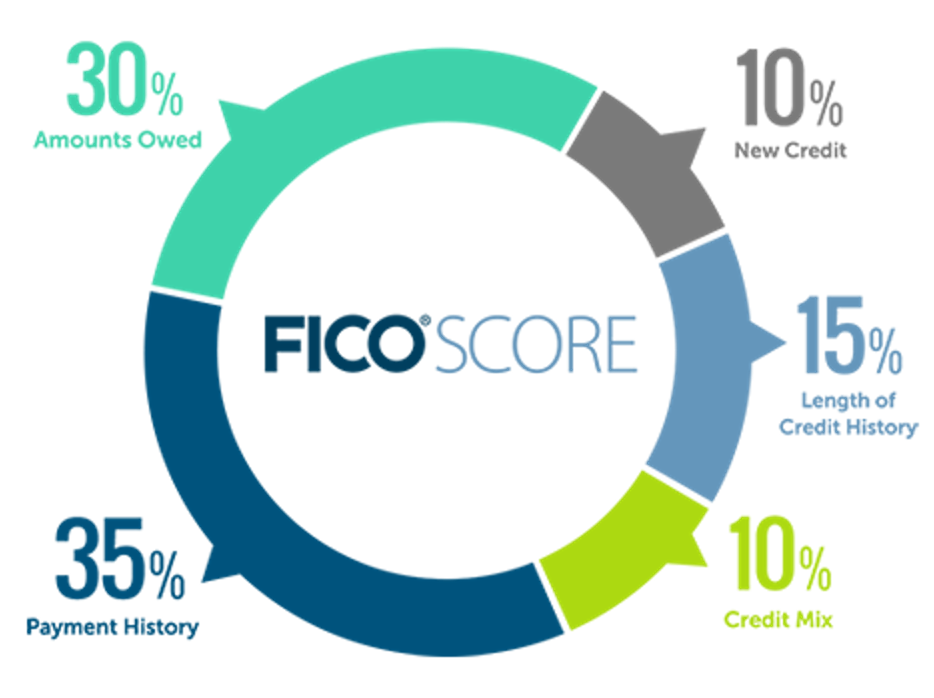

Credit history is obviously the best data to assess willingness to pay. It can also provide a window into a consumer’s financial stability (this is why the age of your oldest credit report tradeline has such a big impact on your credit score).

However, you have to contort traditional credit data quite a bit in order to be able to infer anything useful about a consumer’s ability to pay.

A good example is inquiries. Inquiries are a record of all the times that a consumer has applied for credit. They are captured in the credit file and are a significant factor in most credit scoring models (including the FICO Score and the VantageScore).

Why do inquiries matter to lenders? What behavior are they trying to detect?

To a credit risk professional, inquiries are a signal of possible financial distress. If you lose your job and find yourself headed towards a liquidity crunch, a logical next move would be to stockpile as much access to credit (credit cards, unsecured personal loans, one more loan for a new car, etc.) as you can before you start missing payments and harming your credit score.

This financial desperation can sometimes be inferred from a large number of inquiries on a person’s credit file within a short period of time. That’s why inquiries are captured by the credit bureaus and used as features within credit score models.

That said, inquiries are a very slow and imprecise way of detecting financial distress.

Ohh my god, Alex just applied for unsecured credit three times in the last 70 days. Why? What does he want all of that credit for? Is something wrong? Did he lose his job? Is he not going to be able to pay his bills?

Maybe! Or maybe everything is fine with my job and finances, and I’m just planning to remodel my kitchen.

It’s difficult to tell, just from looking at inquiries.

The reason we rely on inquiries in traditional credit scoring isn’t because they’re the best tool for the job. It’s because, when credit files were being digitized and the first credit scoring models were being built in the 1980s and 1990s, they were the only tool that we had!

This is where plugging in cash flow underwriting, enabled by programmatic, consumer-permissioned access to bank transaction data, can add A TON of value.

Do you want to know whether I’ve lost my job and am going to be at risk of not being able to continue meeting all of my financial obligations? Just look for disruptions to my normal inflows (direct deposits or other recurring income streams). Shockingly straightforward.

Cash flow data easily answers the important ability-to-pay questions that lenders have traditionally been answering through the contorted use of credit data (inquiries, income estimation models, etc.) or through manual steps in the underwriting workflow (it’s still very common to confirm your income by supplying a copy of your W-2). Cash flow data can also provide a more direct view into a consumer’s financial stability (how stable have their income and spending patterns been over the years?), which is deeply complementary to what credit data can do in that area.

Be more specific. What would it look like for a lender to overlay cash flow underwriting on top of traditional underwriting based on credit data?

You want numbers? I’ll give you numbers!

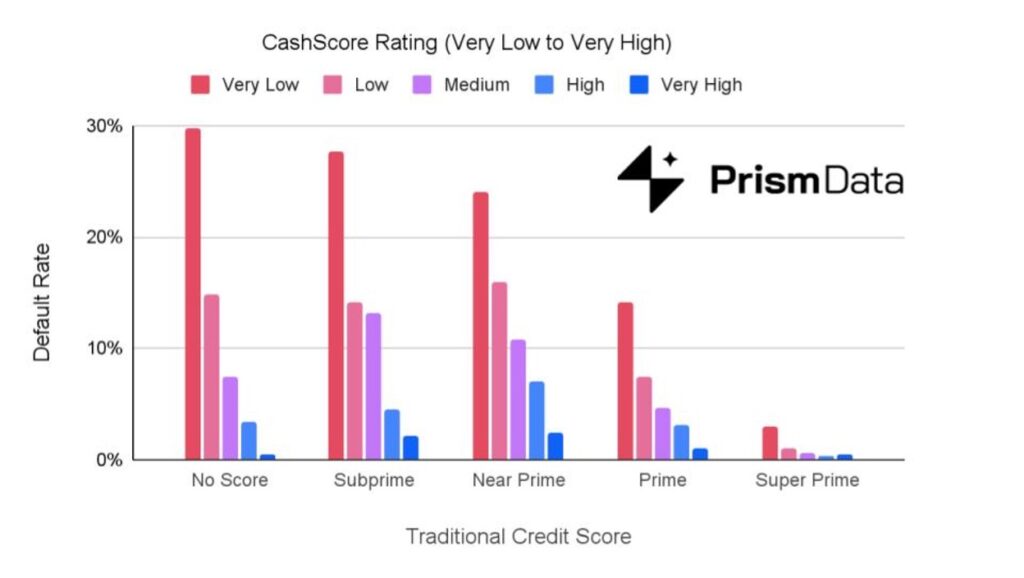

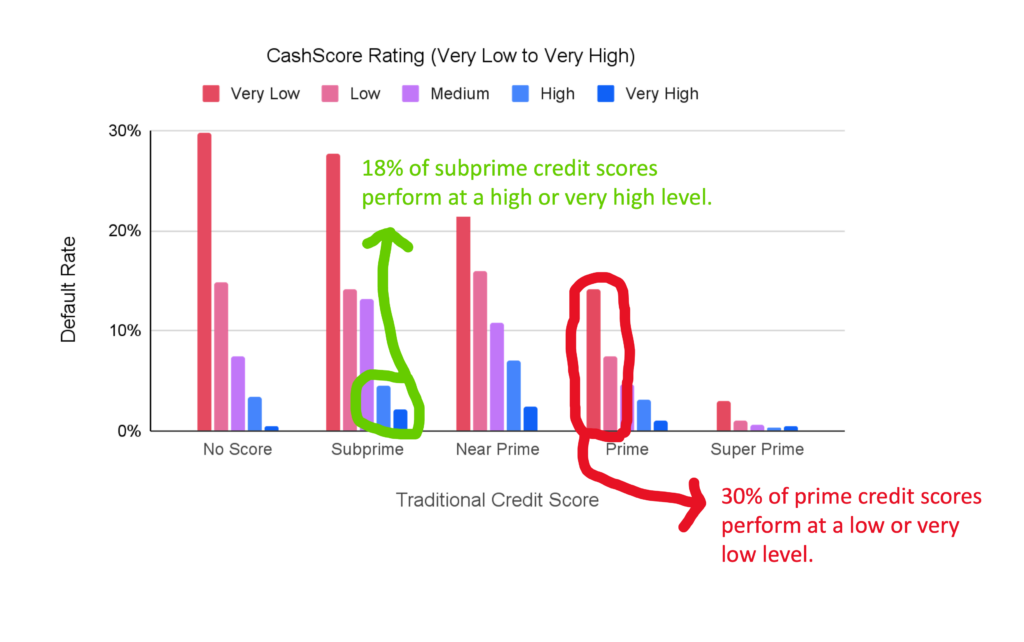

Prism collected performance data from a representative sample of lenders from 2019 to 2023. They split the loan performance out by traditional credit rating (subprime to super prime) and by their CashScore rating (very low to very high). In each category based on traditional credit scoring, they found that cash flow underwriting could be used to further segment those populations into distinct categories of risk.

When you look at the distribution of the population across these risk segments, it becomes clear just how big of an opportunity we’re talking about.

Cash flow underwriting is often thought of as a solution for thin-file and no-file consumers – and indeed, it is likely the most powerful risk-scoring tool available for these populations. However, it also provides meaningful value in underwriting consumers with full traditional credit files across the entire credit risk spectrum from super prime to subprime.

Is that it?

[Mona Lisa Vito voice] No, there’s more!

In addition to providing complementary signals to what traditional credit data provides, cash flow data is also able to correct for some of the material weaknesses in our traditional credit reporting system.

According to a 2012 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) study, about 26% of consumers have at least one potentially material error on their credit report. This isn’t terribly surprising, given that the data is furnished from accounts that consumers rarely monitor via an archaic process (👋 Metro 2!) that consumers neither see nor control.

And even when the data is correct, it’s rarely fresh. Most lenders furnish data to the bureaus on a monthly cadence, which aligns with the repayment cycles for their loan products.

By contrast, cash flow data, which is sourced in real-time directly from consumers’ bank accounts with the consumers’ explicit permission, is highly unlikely to have errors because, well, ensuring that data is accurate is one of the core jobs of all regulated banks (it’s also the exact same data that consumers are checking on a regular basis through their digital banking apps, so any errors that do happen are swiftly corrected).

Additionally, in the same way that traditional credit data can be used to infer certain insights in the realm of ability to pay, so too can cash flow data be stretched to help fill in gaps on the willingness to pay side of the ledger.

Despite their best efforts, the big three credit bureaus have far from perfect data coverage when it comes to important non-credit repayment obligations (rent, utilities, etc.) and novel credit products (such as BNPL).

Analysis of bank transaction data can identify these recurring payment obligations, thus shedding important light on willingness to pay behaviors that would otherwise be missed.

Where are the challenges with cash flow underwriting?

Unlike traditional credit underwriting, which we’ve had 50+ years to refine and work the kinks out of, modern cash flow underwriting is still very new. And like Ford trying to catch up to Tesla, there are going to be plenty of challenges as lenders reintegrate cash flow data into their systems and processes.

Here are a few challenges that are top of mind for me.

Connectivity and the User Experience

Modern cash flow underwriting is dependent on consumer-permissioned data sharing, and consumer-permissioned data sharing isn’t without its hiccups. Open banking in the U.S. is still market-led, which means that its reliability is subject to banks and data aggregators (Plaid, MX, Finicity, Akoya, etc.) getting along with each other. That frequently does not happen, which means connections are constantly breaking, resulting in poor user experiences.

So poor, in fact, that many lenders are justifiably nervous about putting consumer-permissioned data access at the beginning of their account opening user journeys. Instead, many are dropping it into their journeys at the end, either as a second look for applications that are about to be denied or as a way to improve the pricing or terms after a provisional approval.

Improvements in open banking, both technological (credential-less permissioning) and regulatory (the CFPB open banking rule will mandate APIs and minimum up-time standards), have the potential to ameliorate much of the friction associated with connecting external accounts.

Depth of History

Much like traditional credit data, the value of cash flow data goes up the more of it that you have. This is particularly true when it comes to assessing a consumer’s financial stability, where more history is always strongly preferred.

The draft version of the CFPB’s rule on open banking requires data providers to share at least 24 months of historical transaction data, which would A.) be an improvement over the status quo supported by many banks today and B.) likely establish a ceiling of 24 months of history, which would be unequal to the depth of data held by the credit bureaus on full-file consumers and insufficient to fully support certain use cases (like mortgage lending).

Additionally, because modern cash flow underwriting is still so new, there is limited performance data available to help lenders model and benchmark their own performance, especially across changing macroeconomic and credit cycles (which is a critical concern for all lenders). This performance data gap is an issue that can only be solved with time (though it’s helpful that companies like Prism now have cash flow performance datasets stretching back over 10 years).

Secondary Use

Another potential stumbling block in the CFPB’s draft rule on open banking is the bureau’s tight restrictions on secondary use.

The CFPB’s draft rule includes a blanket prohibition on third parties processing covered data for secondary purposes – i.e., any collection or use beyond what it is “reasonably necessary” to deliver the product or service requested by the consumer. This includes marketing or cross-selling additional products and R&D for future product development. This prohibition would apply even if the data was de-identified.

Cash flow underwriting depends on secondary use. You can’t build attributes or scoring models without being able to analyze de-identified bank transaction data. That’s how FICO and the credit bureaus build their analytics. And it’s how the first few generations of modern cash flow analytics were built as well.

Given the CFPB’s clearly stated objective of enabling this type of underwriting, I am reasonably optimistic that the CFPB will relax this secondary use prohibition in its final rule, but we’ll see.

Consumer Education

In the last 10 years or so, we’ve come a long way in getting consumers to be more comfortable sharing their bank transaction data. This is a credit to data aggregators and other fintech infrastructure companies that worked to enable this data sharing safely, as well as the B2C fintech companies that built products and experiences that were worth sharing your data to access.

That said, I think we still have a ways to go in educating consumers when it comes to open banking broadly, and cash flow underwriting specifically.

Consumers understand the FICO Score. They know what it means, why it’s important, and what goes into it.

It will be incumbent upon lenders and cash flow analytics providers to develop and distribute new tools and educational content that help consumers understand the value and intuitive fairness of cash flow underwriting, relative to traditional credit scoring.

Compliance

Speaking of fairness, I would guess that we will encounter some interesting challenges in the next 5-10 years as lenders explore the boundaries of how cash flow data can be used within fair lending laws and other consumer lending regulations.

In the world of traditional credit data, these boundaries are very clearly marked and well-trodden. In cash flow underwriting, I would say the understanding of these boundaries is more conceptual, and their applicability to new insights that can be generated with cash flow data is less clear.

For example, with cash flow data, a lender can easily analyze the categories in which consumers spend money (groceries, entertainment, travel, etc.) Would the use of transaction category insights in the credit decisioning process result in a disparate impact on protected classes under Reg B? I have absolutely no idea, but I’m guessing that regulators will ask questions like that.

Fortunately, the infrastructure providers in the cash flow underwriting space — especially those who have operated for a number of years in regulated contexts — are generally very well aware of these issues and prepared to help their clients navigate them.

Securitization

As I have written about, one of the reasons the FICO Score is so difficult to disrupt is that its hold on the secondary market is very strong. Historically, lenders had to use the FICO Score if they wanted to be able to securitize their loans and sell them on the secondary market. This was due to a combination of familiarity (investors understood and trusted the FICO Score) and, in the case of mortgage-backed securities, regulatory requirements (for years, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac required FICO Scores on all conforming mortgages).

It’s difficult to envision exactly how cash flow underwriting will fit itself into the loan securitization process, but, at the same time, it feels inevitable that it will squeeze itself in there somehow.

In mortgage, Fannie and Freddie (and their regulator, The Federal Housing Finance Agency) are loosening up the restrictions on the data and scores that must be provided with conforming mortgages and are encouraging lenders to utilize cash flow underwriting for credit-invisible borrowers.

More broadly, secondary market investors are becoming much more sophisticated in their analysis of consumer loans, as non-bank lenders like Upstart and Affirm have taken bigger and bigger pieces of the market. And as the private credit industry continues to grow, I would not be surprised if investors proactively embrace cash flow underwriting in order to generate an edge.

OK, last question. Long-term, how do you expect cash flow underwriting to reshape the lending ecosystem?

We know that cash flow data can be used in place of traditional credit data to safely underwrite credit-invisible consumers. We know that cash flow data can strengthen specific weaknesses in the legacy credit reporting ecosystem (data accuracy, freshness, coverage). And we know that cash flow data can add significant predictive power, on top of traditional credit data, when underwriting full-file consumers across the credit risk spectrum.

Given these facts and given the powerful regulatory and public opinion tailwinds behind open banking in the U.S., it is inevitable that cash flow underwriting will become a major component of every lender’s business.

The downstream implications of this shift – which may take 20+ years to fully manifest – will be fascinating.

It seems obvious that it will result in the approval of more low-risk consumers for loans (and, correspondingly, the denial of more high-risk consumers), which will lower the overall cost to borrow for all consumers.

Perhaps less obvious, I think the mass adoption of cash flow underwriting will lead to significant changes in the ways that the traditional credit bureaus operate (pay attention to the collision of rulemaking by the CFPB on open banking and the FCRA) and the ways that consumer lending regulations are applied to consumer-permissioned data (could we see lenders be required to accept cash flow data for credit-invisible consumers in the future?).

Personally, I can’t wait to see how it all plays out.

- Proving my point, VantageScore (the credit score provider created by the three credit bureaus) launched a new version of its score that takes cash flow data into consideration last week. ↩︎

- The language here is important. The FICO Score doesn’t tell you how likely a consumer is to default on a loan. The FICO Score rank-orders the risk of credit default within a population. It is a relative measure. Not an absolute one. It tells you how likely a consumer is to default compared to another consumer. Risk scores built on cash flow data operate in a similar fashion. ↩︎

- In addition to these 36 million unscorable consumers, the credit bureaus estimate that there are 30-35 million thin-file consumers who are scorable. It’s likely that this population could benefit from additional data to evaluate their creditworthiness. ↩︎