As regular readers of this newsletter know, I spend a lot of my time carefully reading the rules set by regulatory agencies and parsing the public statements made by regulators.

I feel strongly that this is a good use of my time.

Opportunities for regulatory arbitrage are plentiful in financial services. However, they also tend to be short-lived and end violently.

Avoiding these violent ends requires understanding not just the letter of the law (not my specialty anyway … NOTHING IN THIS NEWSLETTER IS EVER LEGAL ADVICE!), but also its spirit.

So, in that … spirit, here are three updates on the regulatory front.

The CFPB Finalizes Rule on Standard Setting for Open Banking

As I reported back in March, the fight over standard setting for open banking under the CFPB’s soon-to-be-finalized Personal Financial Data Rights rule (AKA Dodd-Frank Section 1033) has been happening quietly for months.

The basics of the fight are this:

- The CFPB has (wisely, IMHO) taken the position that it shouldn’t directly be responsible for determining and managing the technical standards through which open banking is enabled in the U.S. Instead, it would like to empower an industry-led standard-setting organization (SSO) to do that work.

- The Financial Data Exchange (FDX) is the dominant standards body for financial data sharing in the U.S. and the obvious choice for the CFPB’s officially recognized SSO. However, the CFPB has had some concerns about the structure and governance of FDX, which have made it reluctant to formally recognize FDX as the SSO (more details on that here).

- Once the rule for 1033 is finalized, compliance deadlines for different participants will quickly approach (as quickly as six months for some). The CFPB knows that it can’t expect compliance to be achieved within those deadlines if it doesn’t give industry participants assurance that they are building to the official standard. That means that the bureau can’t wait too long to officially designate FDX (or a different SSO). This has set up a very interesting game of chicken between FDX (and its different member constituencies) and the CFPB.

That game of chicken escalated this week with the CFPB finalizing a rule “establishing a process for recognizing data sharing standards and preventing dominant incumbents from squelching startups.”

As you’d likely expect, the rule itself (which you can read here) is written in a vague and unspecific way, but I think we can still tease out a few of the messages that the bureau is trying to send to FDX:

- Balance means everyone. The CFPB’s desire is to ensure that the composition and influence of the SSO’s membership are balanced across all industry stakeholders. The final rule reiterates the importance of balance while calling out a few specific points. First, the rule distinguishes between small and large commercial entities. The idea here is that an SSO can not be considered to have balanced participation if one group of participants (say banks, for example) is only represented by larger entities. Second, the CFPB explicitly included “data recipients” as an interested party in this final rule. The intent of this seems to be to encourage companies receiving the data (which today is mostly fintech companies) to be actively and directly involved in standard setting, rather than outsourcing that work to data aggregators (which may not be fully aligned with their interests). Third, the rule makes it clear that the CFPB can consider an entity’s ownership structure when assessing how balanced the various levels of an SSO’s governance model are. For FDX, this appears to be aimed squarely at the banks and Akoya, which today play separate roles within FDX, even though Akoya is owned by a group of big banks.

- Consensus doesn’t require unanimity. A couple of the big banks have been trying to convince the CFPB that because most of the costs to comply with 1033 will fall on data providers (i.e. banks), any decisions made by a financial data-sharing SSO should require unanimous approval from all data provider SSO members. The CFPB wasn’t convinced by this argument, writing, “While consensus is important, privileging one group of members would inappropriately give that group unwarranted influence.”

- We reserve the right to “participate”. Andrew Grant, Co-founder and Partner at Runway Group (and a very good basketball player), pointed out an interesting caveat that the CFPB included at the end of its rule – “The CFPB has granted itself significant discretion to intercede in standard-setting activities through the terms and conditions it will impose. Specifically, the rule states, ‘[t]he procedures highlight terms and conditions related to CFPB observation or participation in standard-setting activities…’. While observation and requesting materials are understandable, the rationale for direct participation remains unclear as does what it means to ‘participate.’ Will the CFPB vote? Look to overrule something unilaterally via the terms it imposes even if the standard or process is otherwise approved because it meets the requirements the CFPB imposed by regulation?”

How will all of this play out?

The expectation, based on the timeline outlined in the rule, is that the CFPB will begin accepting applications from aspiring standard-setting organizations in July. Will FDX make the changes that the CFPB wants to see before applying? Or will FDX take the position that the changes to its structure and governance that it has already been making are sufficient? If FDX holds the line, does the CFPB have an alternative SSO that it would be willing to empower? Or, in a last case scenario, would the CFPB be willing to directly set the standards for 1033 itself?

No one who I have spoken with knows the answers, but these are the questions they are asking.

The FDIC Warns Consumers About Third-Party Apps

In what I’m sure is a pure coincidence of timing, the FDIC recently published a consumer news bulletin on the risks of banking with third-party apps:

Increasingly, some consumers are choosing to open accounts through nonbank companies (typically online or through mobile apps), such as technology companies providing financial services (often referred to as fintech companies), that may or may not have business relationships with banks. If and how a bank is involved is key to understanding whether or not your money is protected by deposit insurance. However, in some cases, it is not always clear to consumers if they are dealing directly with an FDIC-insured bank or with a nonbank company.

It is important to be aware that nonbank companies themselves are never FDIC-insured. Even if they claim to work with FDIC-insured banks, funds you send to a nonbank company are not eligible for FDIC insurance until the company deposits them in an FDIC-insured bank and after other conditions are met. If the nonbank company deposited your funds in a bank, then, in the unlikely event of the bank’s failure, you may be eligible for what is referred to as “pass-through” FDIC-deposit insurance coverage.

However, FDIC deposit insurance does not protect against the insolvency or bankruptcy of a nonbank company. In such cases, while consumers may be able to recover some or all of their funds through an insolvency or bankruptcy proceeding, often handled by a court, such recovery may take some time. As a result, you may want to be particularly careful about where you place your funds, especially money that you rely on to meet your regular day-to-day living expenses.

I apologize for the overly long pull quote, but if you found your attention wandering a bit while reading it, imagine how unlikely it is for consumers who haven’t yet run into a Synapse-sized problem to seek out, read, and understand the full article from the FDIC.

This brings me to a larger thought – financial services regulators need to get way better at proactively communicating with consumers.

I know the prudential regulators do their best with the resources and other priorities that they have, but as the financial services ecosystem becomes more complex, the ability of prudential regulators to indirectly protect consumers by ensuring a safe and sound banking system goes down. Synapse is a perfect example of this. There have been no bank failures, and yet hundreds of thousands of consumers have had their access to their primary banking providers cut off (which undermines the perception of safety that the FDIC works so diligently to uphold).

The CFPB, which is focused on consumer protection rather than safety and soundness and is incredibly aggressive on consumer education and awareness, provides an interesting example for its prudential cousins to consider. The bureau’s ‘regulation by blog post’ approach annoys bankers to no end, but at times like this, you can understand why they make it a priority.

Perhaps the FDIC should as well.

The OCC Continues to Push on Financial Health

With all the different priorities taking up time and resources among federal and state regulators, I find it surprising that the Acting Comptroller of the Currency continues to spend time encouraging banks to focus on their customers’ financial health.

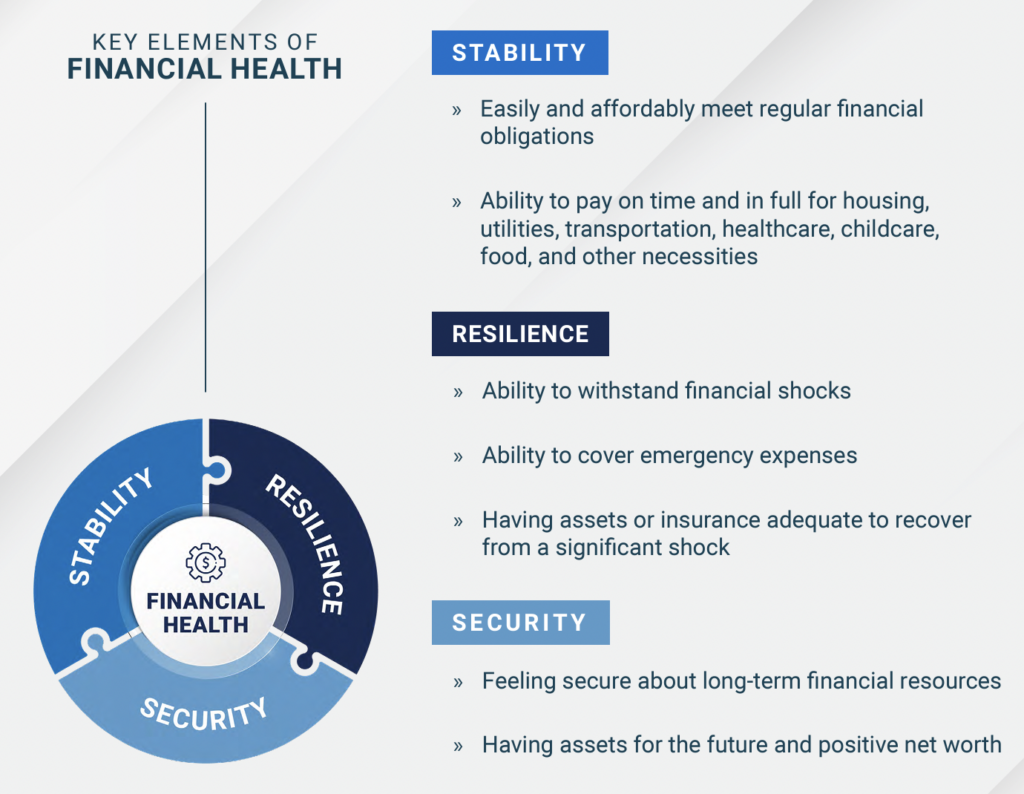

At the Financial Health Network’s annual conference, Acting Comptroller Hsu introduced new research conducted by the OCC on how banks can think about measuring what he calls ‘Financial Health Vital Signs’:

In our Community Development Insights report, as a starting point, we identify three Vital Sign metrics. Vital Signs can be a tool to help identify consumers who are struggling financially and where help is needed most. We would like to engage with banks and others to pilot these metrics and test their robustness and usefulness. Our hope is that the evolution of these Vital Sign metrics (and others that may be developed) will enhance the range of financial health surveys and metrics that have been developed to date and guide consumer banking and financial services in the future. The three Vital Sign metrics discussed in the Community Development Insights Report are positive cash flow, liquidity buffers, and on-time payments.

I really like this initiative from the OCC.

Yes, prudential regulators have a lot on their plates right now, but if you don’t make time for important-but-not-urgent tasks, they never get done.

My question is, how far can the OCC drive the industry on initiatives like this and Project REACh (which is focused on financial inclusion) through research and public encouragement? Can the OCC sell banks on the business value of investments in these areas?

I hope so!