The end goal for financial services companies is to put as much distance between profit and risk as possible.

That’s the goal for companies across all industries, obviously, but in financial services, where risk management is an existentially important function, it’s especially important.

This is the root of the underbanked problem in the U.S.

Market incumbents — the big banks, the card networks, large established non-bank lenders — have the resources necessary to effectively serve the traditionally underserved customer segments in their markets.

However, those customer segments (small businesses, young adults, recent immigrants, etc.) often come with heightened risks (legal, reputational, credit, etc.), and market incumbents, which have the luxury of also serving less risky (and often more profitable) customer segments, will usually choose to focus their resources there, rather than taking on the risks to continually make their products more broadly accessible.

This is enormously frustrating for all of us who want to see a more inclusive and accessible financial system, but it’s also the source of most innovation in financial services.

As Clayton Christensen teaches us, technology disruption tends to start with the customer segments that market incumbents rationally choose to ignore.

In financial services, these tend to be the riskiest customer segments. These segments have always attracted disruptors (long before ‘fintech’ was the term used to describe them), and the creative ideas they come up with to serve those customers have been the driving force behind a lot of important innovations.

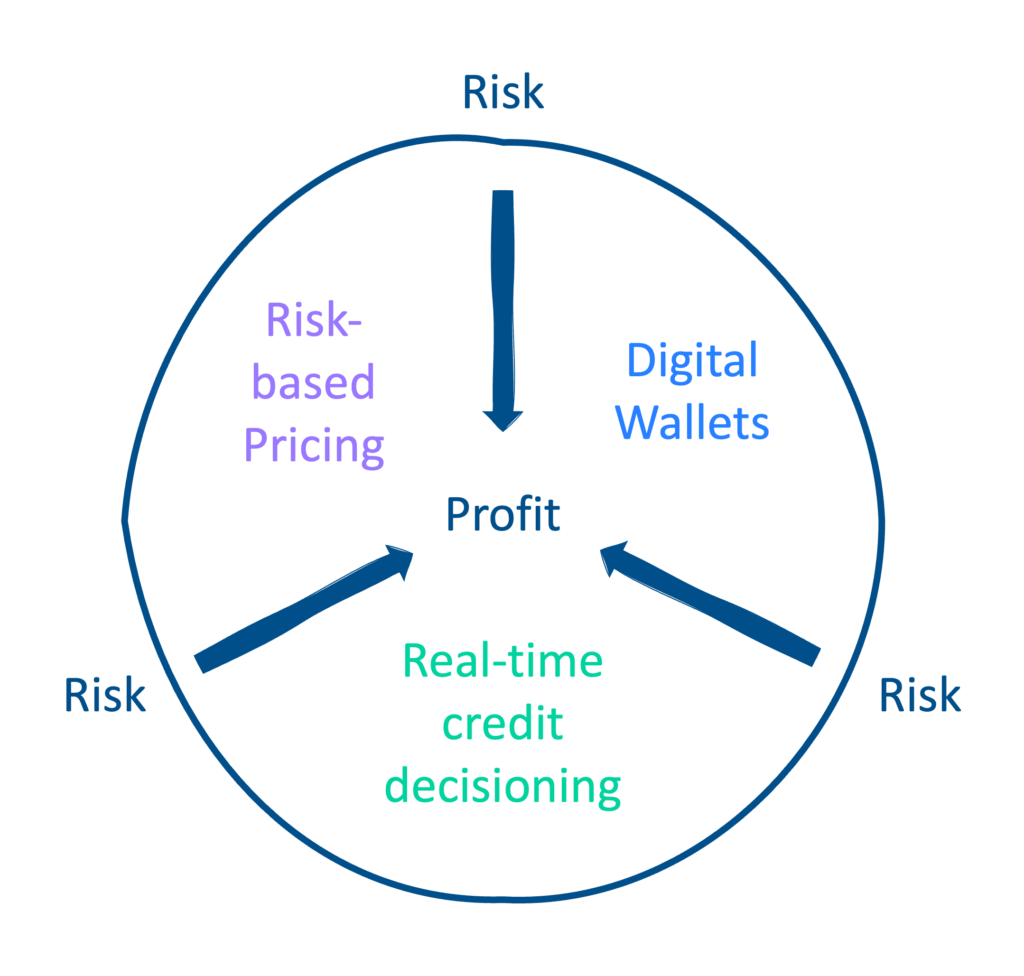

There are countless examples, but I’ll give you three:

- Capital One prices risk more granularly. Until the 1990s, credit cards were homogeneous products. Issuers would offer the same card, with the same features, interest rate, and annual fee to every qualified customer. This naturally constrained the number of qualified customers and the appeal of the product to different customer segments (who valued different features more or less than others). Then Capital One came along and applied statistical analysis to consumer demographic and credit data in order to personalize the pricing and features of their credit card offers to the risks and preferences of granular customer segments. This innovation enabled Capital One to profitably acquire and service a much broader portfolio of customers, across the credit spectrum.

- PayPal makes e-commerce feel safe. In 1999, eBay was one of the largest e-commerce websites in the world. Bizarrely, for the first four years of its existence, eBay did not provide its buyers or sellers with a payment system that they could use to transact with each other. This left users exchanging funds via checks, money orders, and even cash, sent through the mail. Fraud, as you’d likely imagine, was rampant. Enter PayPal, which introduced P2P payments (via email), followed by a stored credential digital wallet, for use in e-commerce transactions (most notably on eBay). These innovations strengthened consumers’ trust in online commerce and contributed significantly to the growth of e-commerce.

- BNPL providers underwrite individual purchases. One of the reasons why credit cards are built around open-end revolving credit lines is because, historically, the process that banks used to underwrite consumers for credit was highly manual and, therefore, very expensive. It was more economical to underwrite a consumer for a larger line of credit, which they could draw upon when needed than it was to underwrite them for credit on a transaction-by-transaction basis (unless the transaction was sufficiently large, like buying a new car). This obviously constrained the number of consumers who could qualify for credit cards (even when leveraging Capital One’s risk-based pricing methodology). However, when BNPL providers like Klarna and Affirm entered the market, wielding fully automated credit decisioning systems that were capable of approving or declining consumers for low-dollar loans for specific e-commerce transactions in real-time at the point of sale, it changed the risk calculus for consumer lending and opened up access to credit for consumers who might otherwise be declined.

Necessity is the mother of invention.

But the beauty is that once these inventions are born, they don’t stay confined to the outer edges of our industry. They permeate every part of it.

Today, every large credit card issuer, regardless of their risk appetite, leverages the marketing segmentation and risk-based pricing techniques developed by Capital One, and many are beginning to incorporate real-time transactional installment lending into their cards, following in the footsteps of Affirm and Klarna. Similarly, P2P payments and digital wallets have become the competitive battleground between banks (Zelle, Paze, etc.) and non-bank payment providers (Cash App, Apple Pay, etc.)

This is why it’s worth paying attention to what’s happening in the riskier, less-heralded corners of financial services. The innovations that happen out there often provide us with a sneak peek of the technologies and challenges that will shape the future of our industry.

For the remainder of this essay, I want to focus on the future of payments in the U.S. And to get a glimpse of that future, I want to look at how payments problems are being solved (or, more to the point, not solved) today in highly regulated industries.

Highly Regulated Industries

First, what is a highly regulated industry?

Highly regulated industries are those that are perceived to have a greater likelihood of fraud, risk, or financial instability, and are, therefore, often subject to greater regulatory scrutiny. Banks and other market incumbents often exercise extreme caution when dealing with customers from these sectors due to potential legal and compliance challenges.

If that definition seems a bit imprecise to you, you’re not wrong.

These industries often exist in gray areas, where the legal status of transactions is uncertain or varies market-to-market.

Additionally, these industries are often seen by banking regulators as too reputationally risky to operate in, even if banks are legally allowed to do so. The idea here — and this is the subject of a lot of legal pushback at the moment — is that banks can lose customer trust and even become financially unstable if they provide products or services to companies or industries that would engender customer complaints or negative media attention.

Two good examples, which are worth double-clicking into, are cannabis and online gaming.

Cannabis, as you likely know, is now legal for recreational use in 24 states in the U.S. and for sanctioned medical use in 38 states. However, it is still illegal at a federal level to sell, possess, or use cannabis products.

The question for banks is, are you allowed to facilitate financial transactions that involve the sale or purchase of cannabis?

And the answer is that it’s really unclear!

Technically speaking, on a federal level, banks (even banks chartered in states where cannabis is legal) that facilitate the sale or purchase of cannabis are facilitating money laundering. However, depending on who is in charge over at the U.S. Department of Justice and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), the level of interest in stopping this activity (and prosecuting it when it does happen) varies.

While this legal uncertainty does leave a very narrow (and very risky) path open to banks that are interested in serving the cannabis industry, it (along with the associated reputational risks) constrains the overall supply of banking services available to cannabis merchants and consumers.

Online gaming is a bit different.

Online gaming isn’t illegal at the federal level in the U.S. And since the Supreme Court overturned the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act of 1992, individual U.S. states have been rapidly legalizing sportsbooks and online gaming (30 states now allow for online gaming).

The challenge, from a financial services perspective, is that online gaming is still illegal in 20 states, and, thanks to the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA), which was passed in 2006, it is illegal for businesses to knowingly accept payments related to unlawful online gaming. The law requires banks, credit card companies, and other payment processors that are interested in serving the online gaming industry to develop systems and procedures to comply with the UIGEA, including monitoring and blocking transactions originating from states where online gaming is illegal. This compliance burden led to some financial institutions opting to avoid processing any gaming-related transactions, even if they might be legal, to reduce the risk of non-compliance.

Banking Is Competitive. Payments Infrastructure Is Not.

The nice thing about banks in the U.S. is that there are a lot of them — more than 4,600.

That means that for every large national bank that is reluctant to venture anywhere near a highly regulated industry, there are hundreds of smaller state-chartered banks that might, under the right circumstances, be willing.

MVB Bank, a small community bank in West Virginia, is a good example:

“We were one of the first to spot opportunities in online gaming, and we’re working to keep up as it grows,” said Larry Mazza, MVB’s chief executive, who oversaw the bank’s pivot in 2018 after the Supreme Court struck down the federal ban on sports betting.

In less than a decade, the bank’s employee headcount has soared from a few dozen employees to nearly 500 workers in 39 states, with recent expansion fueled by pandemic lockdowns that increased online sports betting’s popularity.

The challenge is that while the U.S. banking market is large and diverse enough to provide at least some support to companies in highly regulated industries, the payment processing market is not.

Payment processing is a network-effects business, and the two largest electronic payment network operators in the U.S. — Visa and Mastercard — have no incentive to take excessive risks in order to enable commerce in highly regulated verticals.

For online gaming, this means that the card networks are extraordinarily careful about enabling credit card and debit card transactions and require merchants and banks to conduct enhanced due diligence to ensure compliance with all state and federal laws.

For cannabis, which, again, is still illegal at a federal level, this means that the card networks are incredibly aggressive in identifying and stamping out any usage of their networks for cannabis transactions. For example, a few years ago, Visa told cannabis businesses (and their merchant acquirers) to stop processing cashless ATM transactions in their stores:

Visa sent out a memo to banks that work with cannabis businesses explaining that cashless ATMs, one of three methods dispensaries use to accept non-cash transactions, run afoul of Visa’s rules. Visa, which has a policy against cannabis, says the cashless ATM method is prohibited because it disguises a retail transaction as an ATM withdrawal.

“Cashless ATMs are primarily marketed to merchant types that are unable to obtain payment services—whether due to the Visa Rules, the rules of other networks, or legal or regulatory prohibitions,” Visa’s memo reads. “Therefore, supporting this scheme affects the integrity of VisaNet and the Plus network, as well as the Visa payment system.”

The end result of these challenges is that there is a huge demand in highly regulated industries like cannabis and online gaming, from both merchants and consumers, for innovative alternative payments solutions.

One solution, in particular, has gained a lot of momentum in the last few years — pay-by-bank.

Pay-by-Bank

Pay-by-bank is exactly what it sounds like. It’s a consumer using their bank account details (routing number and account number) to initiate a payment via a bank-to-bank payment rail, such as ACH or FedNow.

Pay-by-bank isn’t a new idea. The national ACH network, operated by the Federal Reserve, came online in 1978, and the Fed set an aggressively low price for banks to use it to send and receive payments (one reason they did this was to entice more banks to join the Federal Reserve System in order to increase the effectiveness of its monetary policy … you can learn more about that history from this Bank Nerd Corner podcast).

Since its inception, market disruptors have leaned on the ACH system as a low-cost alternative to credit cards and debit cards. In fact, PayPal was one of the first internet-era payments companies to leverage the ACH system to reduce payment processing costs. In 2000, the company invented digital bank account authentication using microdeposits in order to enable their customers to easily connect their accounts for pay-by-bank transactions.

However, despite the maturity of bank-to-bank payment rails and the compelling cost savings available to those who use them, pay-by-bank is not a popular choice today. According to a December 2023 survey from PYMNTS Intelligence and AWS, only 36% of U.S. consumers said that they had used account-to-account (AKA pay-by-bank) to make a payment in the prior three months, and a majority of that 36% was driven by P2P payment apps like Zelle and PayPal.

Why is that? Why has pay-by-bank not become a ubiquitous form of payment for consumer-to-business transactions the way that it has for business-to-consumer use cases like payroll?

I think there are a few reasons:

- It’s a clunky experience. Convenience always wins in financial services. Always. And pay-by-bank hasn’t, historically, been the smoothest user experience. Having to type in your routing and account numbers and verify microdeposits in order to link your account is simply too much work for the vast majority of consumers, especially for one-off payment transactions at the point of sale.

- It doesn’t feel safe. Typing in your routing and account numbers isn’t just annoying — it’s scary. Account-to-account payments don’t come with the same fraud protections that credit cards do, and consumers understand this, especially if they’ve had any negative experiences with Zelle or other P2P payment apps, which have been overrun by scammers in recent years.

- Merchants aren’t saving money. Bank-to-bank payment rails are usually significantly cheaper than card rails, but there are two things that are important to remember. First, the vast majority of merchants not named Walmart, Target, or Amazon aren’t motivated by saving money on their payment processing costs. They care about driving sales. They care about increasing their conversion rate. They may be annoyed by interchange fees, but they’re not obsessed with reducing them at any cost. Second, the cost savings that merchants see from pay-by-bank are often outweighed by the losses that they incur from fraud and ACH returns.

- Consumers like their rewards. All things being equal, consumers tend to prefer payment methods that generate rewards for them. Credit card issuers have done a lot of work over the last few decades to strengthen the value propositions of their reward programs.

- Banks and the card networks don’t want to disrupt themselves. On a similar note, unless they are forced to, banks and the card networks are generally reluctant to invest in alternative payment products that have the potential to meaningfully disrupt their existing card products.

Now, the good news is that many of these challenges seem likely to be less severe moving forward.

The ability for consumers to authenticate and link their bank accounts using their account credentials (or, better yet, using passkeys and biometrics) will make the pay-by-bank user experience vastly more streamlined and enjoyable. And, as I have written about before, the CFPB is focused on giving pay-by-bank a big boost through its open banking rulemaking.

Thanks to the rampant fraud and social engineering in P2P payments these days, banks, fintech companies, and regulators have all been spending significant time and resources on figuring out how to make account-to-account payments safer for consumers. This work is necessary and will help pave the road for the broader adoption of pay-by-bank in the years to come.

Finally, banks and the card networks’ willingness to embrace the disruptive potential of pay-by-bank has increased significantly in the last couple of years (Jamie Dimon has forced his employees to explore pay-by-bank, and Visa and Mastercard have both acquired open banking data aggregators), marking an important tipping point for industry adoption.

All of this will help.

However, even with these tailwinds, I don’t think pay-by-bank will become ubiquitous in the U.S. unless we figure out how to solve for some very specific problems.

Fortunately, the experiences of consumers, merchants, and payment infrastructure providers with pay-by-bank in highly regulated industries give us a roadmap for understanding and addressing these problems.

What Cannabis and Online Gaming Can Teach Us About the Future of Pay-by-Bank

Let’s end this essay by reviewing a few of the key lessons about pay-by-bank that have emerged from the highly regulated industries, where pay-by-bank is beginning to see significant adoption.

#1 – Overinvest in data aggregation.

As I mentioned above, open banking is a huge unlock for pay-by-bank. Replacing routing and account numbers and microdeposits with account linking and authentication powered by open banking is a step-change improvement in the user experience.

However, as I wrote recently, the data aggregation infrastructure that powers open banking in the U.S. is far from perfect. The coverage, connectivity, and support provided by individual data aggregators often leave a lot to be desired. This is particularly important when it comes to use cases like payments, where there is a natural expectation for highly performant, always-on infrastructure.

Given this, it’s not a surprise that several of the pay-by-bank providers that focus on highly regulated industries (including Aeropay) have invested in building their own dedicated data aggregation services internally, in order to ensure the best possible coverage, connectivity, and support for merchants.

#2 – Figure out how to solve for ACH returns.

Here’s something I was surprised to learn — a large portion of ACH returns for pay-by-bank transactions in highly regulated industries aren’t due to fraud. They are due to the consumer having insufficient funds in their accounts.

Take online gaming, for example. Transactions will often take place over the weekend, which means that the window of time between when an ACH transaction is authorized and when it is settled can be three to four days (the Federal Reserve’s National Settlement Service is closed on weekends if you can believe that). During that window, consumers will sometimes unintentionally overspend on their accounts, leaving them insufficient funds to settle their original ACH payment.

Bringing these R01 returns down to a manageable level is an essential job to be done for any company that wants to play in the pay-by-bank space. This is usually accomplished by building predictive models that can evaluate consumers’ cash flow patterns and accurately anticipate ACH returns before they happen. However, the eventual mass adoption of real-time bank-to-bank payment rails like FedNow and RTP, which settle transactions instantly, will play a big role in solving this problem as well.

#3 – Have a plan to fight friendly fraud.

That’s not to say that fraud isn’t a big problem in pay-by-bank. It is. And, in fact, according to everyone I spoke with while researching this essay, it’s a problem that is getting worse.

Friendly fraud (also known as first-party fraud), in which a consumer uses their real name and bank account(s) to initiate a transaction that they have no intention of seeing through, is a particularly pernicious and fast-growing part of the problem.

Information on how to commit this type of fraud can be easily discovered through TikTok, YouTube, Reddit, and dozens of other digital channels, and the mere act of posting the information (which is always presented as a tip or a hack, rather than as what it actually is – fraud) creates a permission structure that tells consumers that this type of behavior is acceptable.

Friendly fraud, which is extremely common in highly regulated industries and increasingly prevalent in debit and credit card transactions across all industries, can be mitigated, but it’s tricky. It requires a network-level view of how consumers transact with different merchants over time, as well as a willingness to exclude banks and merchants from your network that tacitly encourage friendly fraud (which is unfortunately something we saw too much between 2019 and 2022).

#4 – Be prepared to steer consumer behavior.

In highly regulated industries like cannabis, there really isn’t much of a need to incentivize or otherwise steer consumers toward pay-by-bank. Given the dearth of alternative payment options available to them, most consumers are happy to try pay-by-bank (as long as it is sufficiently convenient to use).

As pay-by-bank moves into other industries and use cases, where competition from established payment methods is much greater, it is reasonable to expect that merchants will need to invest in more proactively steering consumers towards pay-by-bank and incentivizing them to use it over other payment methods.

This could involve developing new rewards programs to compete with the rewards offered by credit card issuers or leveraging the set-it-and-forget-it nature of stored payment credentials in digital wallets to lock in top-of-wallet status rather than fighting for it during every transaction.

#5 – Find new opportunities to engage customers.

Connecting to a consumers’ bank accounts gives merchants and pay-by-bank providers a unique window into the financial health and behaviors of those consumers. Beyond using these insights to manage risk and fight fraud, merchants and payment providers should view this as an opportunity to build a stronger relationship with consumers.

In highly regulated industries like online gaming, these insights can be applied to encourage healthier betting behavior (or, in more severe cases, to restrict betting entirely). In payments, more broadly, the opportunities for meaningful consumer engagement are much larger.

Pay-by-Bank is Coming Soon to an Industry Near You

It seems likely to me that pay-by-bank will eventually become a major part of the U.S. payments ecosystem. I’m clearly not alone in this opinion, as the big investments made by banks and the payment card networks in pay-by-bank and open banking have demonstrated.

However, the time it takes for the U.S. to get to this end state will depend on how quickly the industry internalizes the lessons learned by emerging pay-by-bank leaders like Aeropay in building the required infrastructure for highly regulated industries.

This will be harder than it sounds.

It’s not always easy, if you haven’t operated in highly regulated industries, to understand how specific industry quirks might translate from one vertical to another.

For example, as we’ve already discussed, the rate of ACH returns generated due to insufficient funds is often higher in highly regulated industries. If you were to apply pay-by-bank to a different industry that is similarly dependent on cash flow patterns — like utilities — you might consider implementing a predictive model trained on open banking data to dynamically determine bill due dates on a customer-by-customer basis, in order to minimize your number of R01 returns.

Capabilities like this likely wouldn’t occur to market incumbents, but fortunately, the pay-by-bank disruptors that got their start in highly regulated industries are coming soon to an industry near you.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Aeropay.

Aeropay is a leading financial technology company providing open banking and account-to-account payment solutions for businesses. With Aeropay, businesses can offer cost-effective, fast, and secure digital payments to their customers both in-store and online. Enabled by sophisticated technology, with compliance at the core, Aeropay is the better way to move money. For more information, visit aeropay.com.