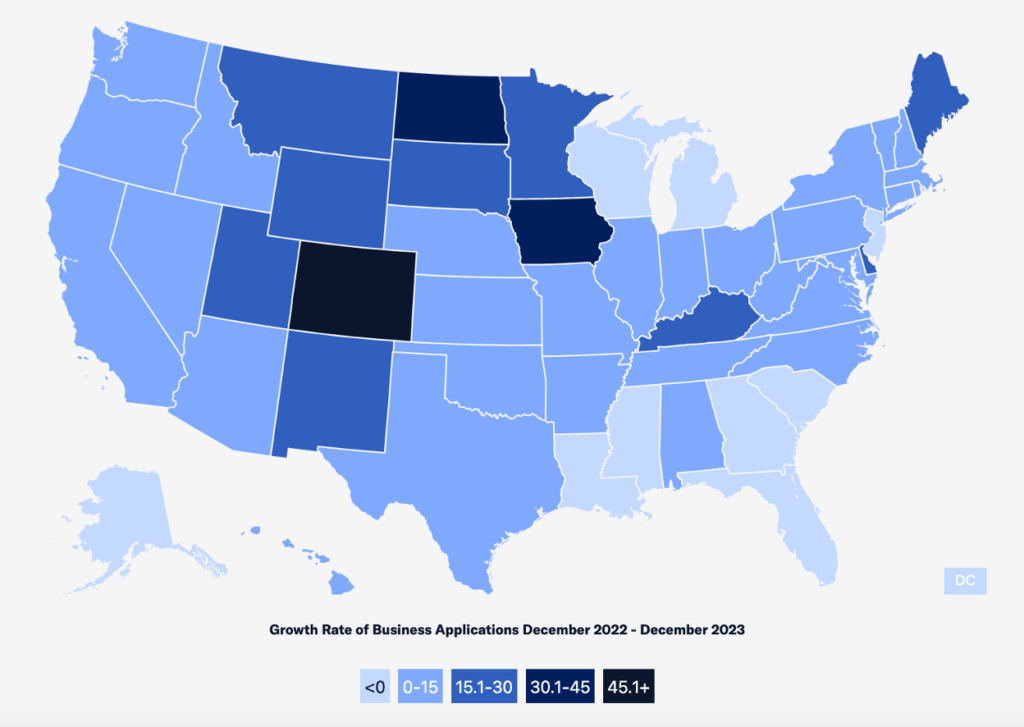

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, almost 5.5 million new business applications were filed in 2023, breaking the 2021 record of 5.4 million. Since 2012, the submission rate for new business applications has more than doubled.

Here’s what the 2023 entrepreneurship growth spurt looks like, broken out geographically:

It’s hard to look at those statistics and not come away feeling optimistic.

It’s cliché to say that small businesses are the engine of the U.S. economy, but it’s a cliché for a reason. Small businesses account for 99.9% of all U.S. companies and nearly half of private-sector employment.

And if small businesses are the engine of our economy, then capital is the fuel.

However, according to nearly every survey that has ever been done of small business owners, that fuel is scarce. Take this January 2024 survey from Goldman Sachs, which found that:

- 77% of small business owners are concerned about their ability to access capital.

- 35% of small business owners have applied for a new business loan or line of credit in the past year.

- Of those who had applied in the last year, 79% found it difficult to access affordable capital, 60% did not receive all of the funding they requested, and 28% of applicants have taken out a loan or line of credit with payment terms that felt predatory.

It’s hard not to look at those statistics and come away feeling pessimistic about the U.S. financial industry’s ability to support American entrepreneurship. Despite all of the innovations introduced by fintech over the last couple of decades, the small business lending gap persists.

In this essay, I will explain why small business lending is so difficult and trace the recent evolutionary history of small business lending in the U.S.

My goal is to outline where we’ve been so that we can more accurately project where we’re going next (and what tools we will need to get there).

Spoiler alert – there are lots of reasons for optimism!

Why is Small Business Lending difficult?

The short answer is that small business lending is difficult because operating a small business is a risky endeavor.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 45% of small businesses fail within five years. Extend that out another five years, and the percentage goes up to 65%.

Lending to an entity with that short of a lifespan is an inherently risky proposition.

The slightly longer answer is that small business lending is difficult because it is rife with information asymmetry.

Information asymmetry – the difference between what the two parties in a transaction know – is a foundational challenge in lending. And in small business lending, it cuts deeply, both ways.

For the lender, it’s always likely that the small business owner knows something about the viability of her business and the competitive environment in which it operates that would make lending to her unacceptably risky, like, for example, if a new bakery is about to open across the street from hers and siphon away 40% of her business.

And for the small business owner, it’s nearly impossible for any lender to see her business with the same clarity and conviction with which she sees it. This isn’t surprising. The lenders aren’t living in the business, day in and day out. They’re not talking to customers or suppliers. They’re not executing marketing campaigns or restocking inventory. It’s not surprising that lenders don’t understand small businesses as well as their owners do, but it can be quite frustrating for those owners when they see opportunities to grow their businesses and lenders won’t give them the capital they need to seize those opportunities.

So it didn’t come as a shock to me that 60% of small business owners who applied for a loan or line of credit last year didn’t receive all of the funding they requested.

Not shocking, but it is a problem.

As a society, we want to maximize the amount of responsible lending to small businesses. We want to put as much capital into the hands of entrepreneurs as we safely can, especially at a time when entrepreneurship is surging.

The question is, who is going to do it?

I have a theory.

I believe that the ideal small business lender is one that has the following four characteristics:

- Delivers a fast and convenient borrower experience.

- Has useful first-party data.

- Specializes in a specific niche.

- Has a balanced and sustainable business model.

The best way for me to explain each of these characteristics is to quickly review how small business lending in the U.S. has evolved over the last two decades.

The Recent Evolutionary History of Small Business Lending

OK, let’s start at the beginning.

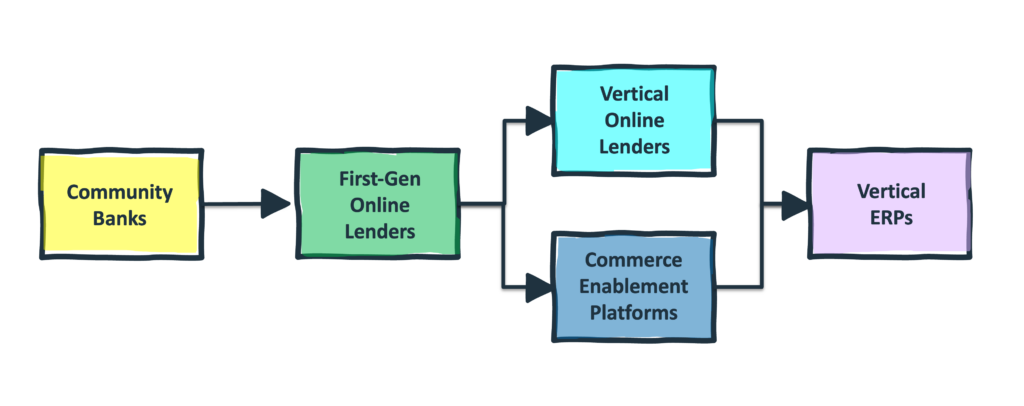

Community Banks

Historically, community banks have dominated small business lending.

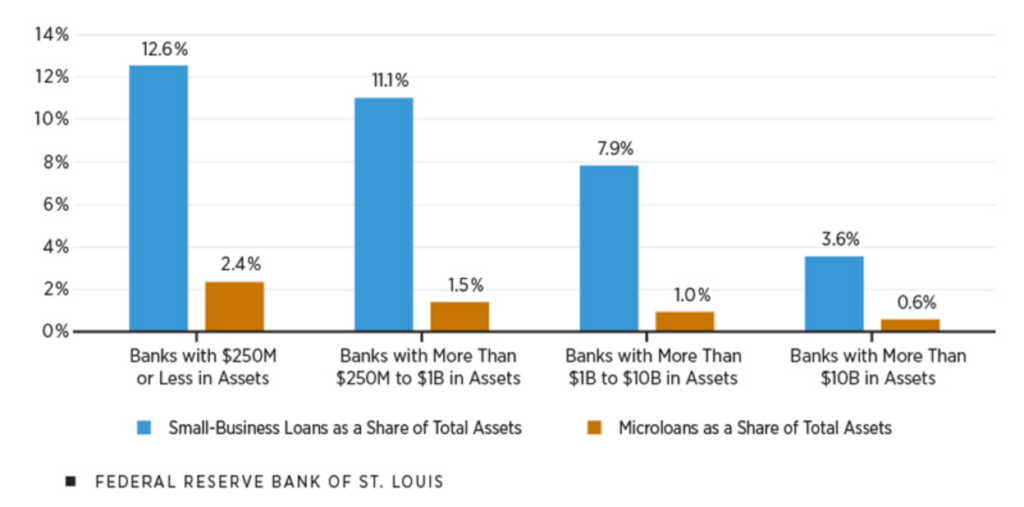

According to an analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, small business loans (loans under $1 million) and business microloans (loans under $100,000) made up a significantly higher share of community banks’ total assets than they did for regional, super regional, and national banks:

This is due, in part, to bigger banks ignoring small businesses, in favor of building larger and more profitable businesses in consumer and commercial lending.

However, it’s also due to the fact that community banks are really good at serving small businesses!

Community banks specialize in serving their communities (hence the name). These communities are most often defined geographically, which means that community banks are uniquely well-positioned to lend to brick-and-mortar small businesses that are located in their towns or cities because, well, the loan officers working at those banks also live in those towns and cities. They understand, for example, if the local bakery will be adversely impacted by a second bakery opening up across the street.

Community banks are multi-product relationship businesses. They loan money to small businesses as part of a larger (and very-well-tested) business model, which also includes selling other small business financial products (deposits, payments, wealth management, etc.) and consumer financial products to the business owner and employees. This multi-product relationship creates a depth of first-party data (payment transactions, financial planning and forecasting, etc.) that gives the bank an even richer understanding of their small business customers’ financial condition and needs. It also gives banks an incentive to invest in protecting and expanding their relationships with their small business customers, which manifests in excellent customer service and competitive pricing and terms in their lending products.

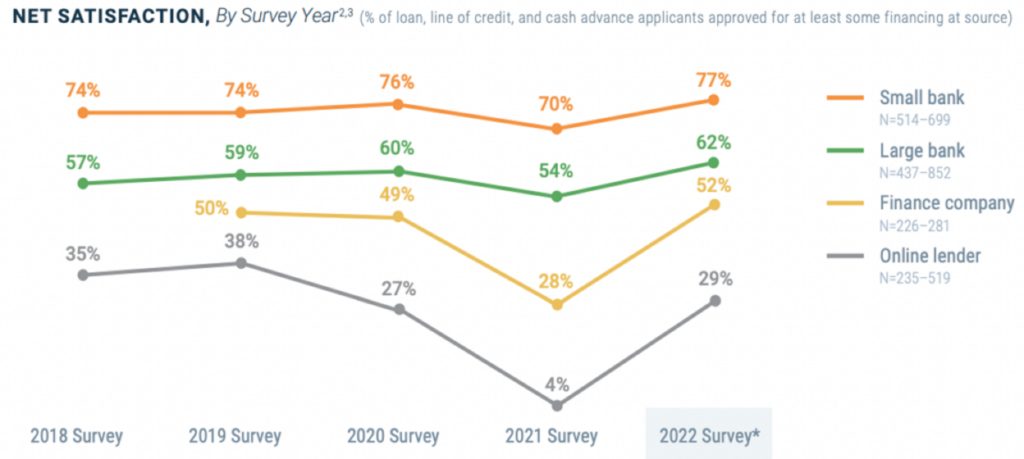

Little wonder then that the Federal Reserve found that small banks have consistently beaten out big banks, online lenders, and specialty finance companies when it comes to customer satisfaction in small business lending:

Small business owners love everything about working with community banks.

Well, almost everything.

First-Gen Online Lenders

In the early 2010s, small business lending volumes began to shift towards online lenders like Kabbage and OnDeck Capital.

These providers captured this volume by exploiting the one big weakness in community banks’ small business lending processes – a lack of speed and convenience.

First-gen online lenders looked at the 25-30 steps in the traditional small business loan underwriting process and found numerous creative ways to streamline, automate, and resequence those steps, reducing the application-to-funding cycle for small business owners from days or weeks to hours or minutes.

This focus on creating a faster and more convenient borrower experience was a huge deal.

In small business lending, speed kills.

Small business owners will always say that they want competitive pricing, responsive customer service, and the convenience of working with one banking provider … and they do. However, the success of these online lenders proved that those wants are second-tier priorities compared to the desire for fast and frictionless funding.

Remember, capital is the lifeblood of a small business. When you are running low on blood, you don’t quibble over the cost of a transfusion or the bedside manner of the nurse. You do whatever you have to do to survive, and you worry about (and complain to researchers at the Federal Reserve about) the consequences later.

This is how this first generation of online lenders captured a significant chunk of the small business lending market in the U.S. in the 2010s, despite small business owners consistently ranking them last in customer satisfaction.

It has not proven to be a sustainable model.

As non-bank monoline lenders, these companies struggled to construct a sound business model. High customer acquisition costs on the front end, combined with the high cost of capital on the back end, produced poor unit economics. And unlike many other areas of financial services, where there is at least the hope of getting to improved unit economics by achieving greater scale, lending is an anti-scale business. The faster you attempt to grow it, the more risk you take on (either intentionally or through increased adverse selection) and the more pressure you put on your pricing.

Additionally, the first-gen online lenders were industry agnostic. They didn’t specialize in any specific niche or customer segment. They went after small businesses indiscriminately, using a one-size-fits-most product set and automated lending platform that didn’t leave much room for nuance. This was fine because, as monolines, they lacked the differentiated first-party datasets that could facilitate a more personalized approach to product development and underwriting.

These challenges led to less-than-stellar exits for many of the big online lenders of that era (OnDeck was acquired by Enova, and Kabbage was acquired by American Express) and opened the door for new competitors.

You can organize these new competitors into two groups.

Vertical Online Lenders

The first is fairly straightforward – vertical online lenders.

These are the spiritual successors of Kabbage and OnDeck, and they provide a similarly fast and convenient borrower experience. However, where Kabbage and OnDeck targeted everyone, vertical online lenders specialize in specific industries and customer segments. For providers in this category, specialization removes a lot of the variability that makes underwriting small businesses so tricky. It enables these lenders to approve a higher number of applicants (at a wider range of sizes) from their industries, which builds their brand awareness and reputation. This drives lower-cost customer acquisition and positive selection, which, in turn, leads to safer risk decisions and the ability to approve more applicants.

Put simply, specialization makes lending less of an anti-scale business.

Additionally, while vertical online lenders typically lack first-party data that would be useful for making lending decisions, they at least understand the value of such data, and they will, where possible, look to access it (with their customers’ permission). This is why so many of the vertical online lenders that have popped up in the last five years (Ampla, Wayflier, Pipe, etc.) started out focusing on e-commerce, where APIs to access real-time sales and inventory data are readily available.

However, despite these innovations, vertical online lenders have already shown signs of the same business model vulnerabilities (high costs, concentrated revenue mix, etc.) that undermined Kabbage and OnDeck. A recent New York Times article about Ampla, which specializes in direct-to-consumer brands, illustrates the point well:

Firms that worked with Ampla said that the company moved fast and that its employees were sharp and friendly. It accepted collateral that other lenders would not. Many borrowers signed on because Ampla offered relatively low rates — and kept them at those levels even as the Fed raised its benchmark rate.

But as the Fed kept its benchmark rate high for months, Ampla’s costs became onerous. It had to start raising the interest rates of the loans it made, undercutting its appeal to smaller brands, the person said.

Ampla made loans that one of the people familiar with its finances said appeared not to meet the standards the company had set for itself. Some of those customers ended up not abiding by the terms or fell behind on payments, the person said.

Commerce Enablement Platforms

The second group of companies is a bit more complex and interesting.

You’ll immediately recognize the names – PayPal, Square, Stripe, Shopify – which I refer to collectively as commerce enablement platforms.

As you know, each of these companies offers entrepreneurs a suite of services designed to help them run and grow their businesses. These services include everything from marketing to inventory management.

But the reason we care about them in fintech is that a subset of those services are financial. This is what is commonly referred to as embedded finance.

Payments is the most common starting point. Indeed, three of the four companies that I mentioned above started out helping merchants process payments from their customers, before bundling their way into the broader commerce enablement platforms that we know today.

And the neat thing about embedded payments, for the purposes of this essay, is that it is an excellent enabler for embedded lending.

Payment transactions are an incredibly valuable first-party dataset for making lending decisions. It gives the commerce enablement platforms a detailed, real-time view into small businesses’ cash flow and ability to pay. This insight is not only useful for loan underwriting. It can also be used to predict when a small business may be in need of additional capital, allowing the commerce enablement platform to proactively offer a loan before the small business owner can even think to ask for it. And because the commerce enablement platform sits within the small business’s flow of funds, loan payments can be automatically collected without the small business owner needing to lift a finger. Talk about fast and convenient!

The business models of these companies vary. PayPal and Block (Square’s parent company) have both B2B and B2C businesses. Stripe is both a commerce enablement platform and an infrastructure provider to other commerce enablement platforms (more on that in a bit). Shopify is Shopify. The thing they have in common is that they are well-balanced and sustainable.

The only drawback of these platforms, from a small business lending perspective, is that they are generalists, not specialists. This lack of focus on a specific vertical or niche requires the companies to be decidedly unopinionated in the design of their products, which isn’t a problem for the long-tail of e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, and service small businesses out there but does limit their appeal to larger small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs).

And that brings us to our final chapter – the ideal end state, from my perspective, for this evolutionary journey that we’ve been on – Vertical ERPs:

Vertical ERPs

I’m borrowing the term Vertical ERP or VERP from Matt Brown, a fintech investor at Matrix, who coined it back in 2022. So let’s let Matt define the term for us:

[Small businesses] rely on a patchwork of horizontal software products (think Mailchimp, Typeform, Google Suite, etc). But just as it does with larger companies, this patchwork leads to fragmented data, and fragmented understanding, across business functions. Where’s the source of truth for the list of ‘active customers’? Where’s the single, true, complete list of all products, services, delivery dates? Tools like Zapier and Paragon help with data portability, but don’t provide that single source of truth. These businesses are still stuck juggling multiple logins, monthly subscriptions, and duplicate data.

A vertical ERP (VERP) solves this by bundling all of these tools in one place. Specifically, a VERP:

- is designed exclusively for the business and workflows of one specific vertical (think restaurants, hair salons, florists).

- is built to manage as much of that business’s data and functionality as possible. A VERP is successful if a large number (if not all) employees use it for the majority of their day, to the exclusion of other software products.

- aims to absorb a business’s spending and revenue via fintech products like payments, banking, credit, and more.

Canonical examples of VERPs include Toast (restaurants), Mindbody (wellness), and ServiceTitan (home repair and improvement).

The principal differences between commerce enablement platforms and VERPs are A.) the depth of the products’ non-financial services functionality (commerce enablement platforms focus primarily on sales, marketing, and growth, while VERPs aim to consolidate as much of a business’s data and workflows as possible) and B.) the specialization of the companies’ products (commerce enablement platforms build generic capabilities for a broad swath of small and microbusinesses across industries whereas VERPs build opinionated capabilities for larger and more sophisticated SMBs in one specific vertical).

Similar to commerce enablement platforms, VERPs dramatically improve the speed and convenience of the lending experience for small businesses by embedding a variety of lending products directly within the software workflows that the businesses’ employees use every day.

VERPs also have a significant amount of first-party data that can be applied to improve marketing and underwriting. In fact, the first-party datasets that VERPs generate are often deeper than what either community banks or commerce enablement platforms generate. Here’s Matt again:

Lending is interesting because a VERP has a wealth of data that traditional lenders don’t. Banks underwrite many different types of businesses without much visibility into or detailed understanding of each business’ unique and underlying operations, but a VERP specializes in a specific type of business as part of its operations. The VERP can see all of the business’ activity: leads, clients, seasonal patterns, outstanding payments, etc. For example, although two businesses may have similar top line revenue in a given month, perhaps one’s revenue is highly concentrated in a small number of customers or much of that revenue is from significantly overdue payments. This more granular data gives the VERP a significant edge in underwriting.

VERPs have significant flexibility in designing their business models – blending together financial services revenue with traditional SaaS subscription revenue – in order to balance growth, profitability, and sustainability within their target markets.

Build or Buy?

VERPs are the ideal distribution channel for small business loans. They deliver a fast and convenient experience to borrowers. Their depth of first-party data and opinionated design allows for precisely tailored loan product constructs that meet the requirements of even the most demanding SMBs. And the flexibility of being able to blend SaaS and financial services revenue together ensures that VERPs will be a sustainable distribution channel for small business loans, not a ZIRP-fueled flash in the pan.

Best of all, hardly any VERPs have embedded lending into their products yet!

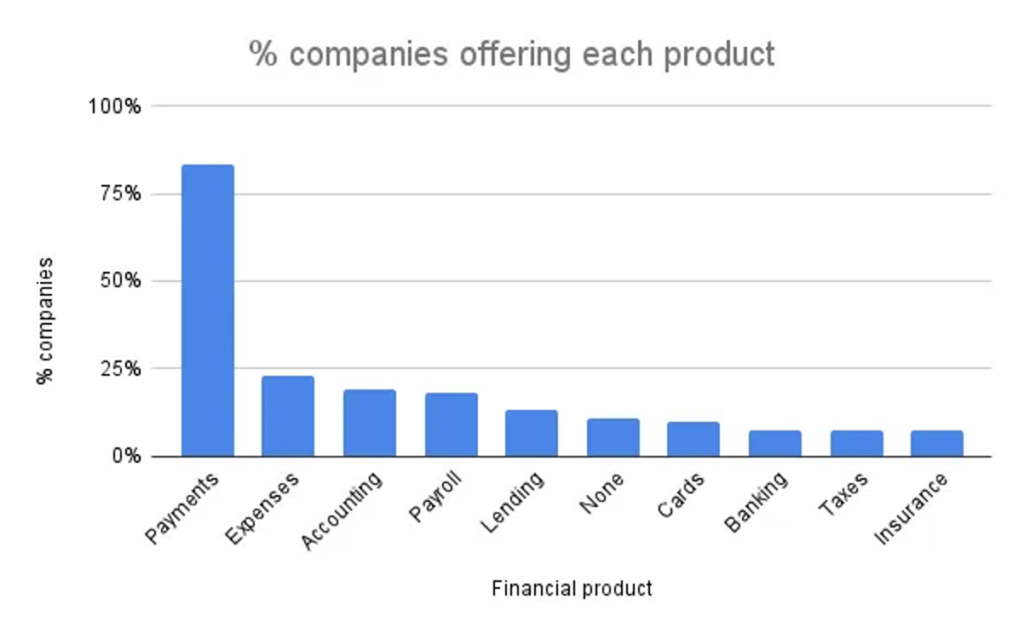

Again, we turn to Matt Brown, who did some great primary research looking at several hundred software companies that could meet his definition of a VERP (explicitly focused on one vertical and offering a multi-product product suite) and analyzing the penetration of different embedded finance offerings within those product suites.

Unsurprisingly, Matt’s analysis found that payments was, by far, the most commonly integrated financial offering within VERPs. What was more surprising to me was how far behind payments lending was, despite the fact that (as we’ve discussed) lending is a natural follow-on product after payments:

Look at how few VERPs have added lending into the mix! Less than 20%, despite 83% already offering embedded payments!

This means that there is a massive untapped opportunity for VERPs to take market share in small business lending away from banks, monoline online lenders, and (to a lesser extent) commerce enablement platforms.

I believe this will happen.

However, the question is, how will it happen?

Will VERPs choose to assemble their own lending products from scratch? Or will they take the more expedient path and buy embeddable lending-as-a-service (LaaS)?

You can certainly see the argument for buy over build.

As I am fond of saying around here, building a lending business is extraordinarily challenging.

To build a profitable lending business, you have to master (among other things): customer acquisition that will drive positive selection, loan underwriting and credit decisioning, loan servicing (including deferrals and modifications), collections and recovery, debt capital management, and compliance (KYC/AML, fair lending, etc.)

Why go through all of that when you can choose from a host of full-service LaaS offerings specifically tuned for verticalized embedded B2B lending?

Stripe, Kanmon, OatFi, Pipe, and Adyen are some of the providers in this space. Their products are all a bit different, but the basic gist is that they offer an end-to-end embeddable lending solution that allows a B2B platform to offer loans to its customers without having to do anything. The LaaS provider handles the underwriting, servicing, collections, debt capital management, and compliance. They take 100% of the credit risk(!) and give the VERP a share of the resulting revenue.

Risk-free revenue! Available through one API!

If it sounds too good to be true, you’re not entirely off base.

Here’s the catch – because the LaaS provider is taking all of the downside risks, they also get to take a healthy chunk of the upside (far more than your typical lending infrastructure provider) and exert almost complete control over how the lending products are structured, marketed, originated, serviced, and collected.

Surrendering that control isn’t a tradeoff that VERPs should make if they can avoid it.

Start with the Relationship and Work Backward

The competitive differentiation of vertical ERPs, like community banks before them, is rooted in the customer relationship.

These platforms know their customers best. Their products are tailored to meet their exact needs. The core of their business model – SaaS subscription fees – is reliant on their customers explicitly choosing to continue working with them.

Given this, VERPs should never view small business lending solely as a revenue driver.

Instead, they need to view it as a mechanism for protecting and strengthening their customer relationships. They need to view it as an opportunity to uncover unmet needs that can inform both their software and fintech roadmaps and to build trust and brand affinity when they help their customers successfully navigate the volatility that is inherent in running a small business.

Put simply, if you’re going to build an embedded lending business within a vertical B2B SaaS platform, you should start with the customer relationship and work backward.

This is why, when it comes to technology, a lot of VERPs are prioritizing loan servicing.

Intelligent Servicing

This quote, from the VP of engineering at a high-growth SaaS company that offers SMB loans, neatly illustrates why loan servicing is often the highest priority when building an embedded lending business:

The complexity and corner cases in building a credit business aren’t in acquiring customers or the loan application journey. It’s everything after that.

Handling that complexity requires adaptability.

Can your systems support dynamic changes to loan terms, due dates, and interest rates at the individual loan level in order to help your customers better weather the cash flow volatility that comes with running a small business? What about at the portfolio level? Or the product level?

Can your systems monitor your customers’ aggregate financial performance and behaviors and identify macro patterns that may impact their ability to pay? Can they enable you to proactively reach out to those customers before they encounter a problem and restructure their loans to reduce the risk of default?

Lending generates friction. Every time a customer falls behind on a loan or has an existing loan’s terms unexpectedly changed in an unfavorable direction, you are increasing the risk of that customer churning and taking their SaaS subscription revenue with them.

Ensuring that you can minimize that friction and be as supportive as possible of your customers’ changing needs is essential for retaining and growing those customer relationships.

Adaptability is also necessary for innovation.

The data generated by your vertical B2B SaaS platform will be a continual source of inspiration as you observe how your customers manage their cash flows. It is critical to be able to quickly develop and launch new loan product constructs to meet your customers’ evolving capital needs.

One example – a vertical B2B SaaS company noticed that a large portion of its customers were trying to take out loans at a specific time in the spring. After investigating, the company discovered that these customers were attempting to take out short-term, low-interest loans to help them finance the costs of their annual tax bills. Rather than continuing to force a square peg into a round hole, the company rapidly designed and launched a dedicated lending product for taxes – 10-week term, no interest, just a small financing charge – BNPL for taxes!

These adaptable systems – what Canopy calls “Intelligent Servicing” – are the foundation upon which the next generation of great small business lenders will be built.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Canopy.

Canopy is a modern platform for managing and servicing business loans, offering flexible infrastructure to launch and scale multiple lending products. Its API-first architecture ensures any brand can embed financial products, go to market with new features faster, and support borrowers with world-class service. This allows fintech and SaaS providers to improve repayment rates and the customer experience while decreasing servicing costs.