According to BAI’s 2024 Banking Outlook survey, customer acquisition was the second biggest challenge that financial services organizations listed for the coming year (number one was deposit gathering, which is obviously highly related to customer acquisition).

In 2023, the biggest challenge that BAI survey respondents listed was … you guessed it — customer acquisition!

In financial services, like in every industry, customer acquisition is critical.

However, unlike most other industries, customer acquisition in financial services has been shaped by some unique constraints.

In financial services, customer acquisition is a function of distribution and competition.

Historically, U.S. banks’ distribution strategies were limited by geography. Interstate banking was illegal, which meant that you could only reach customers in the state (or region within the state) that you were legally allowed to operate in. And even within that state or region, your reach was a function of your branch network. If you wanted to acquire new customers, you had to build (or buy) new branches.

Then, in the early 1990s, we got both the Internet and the Riegle–Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act. These changes leveled out the distribution playing field and allowed everyone to fish in the same (big) pond.

This, of course, opened the door to the modern fintech industry.

Fintech startups intuitively understood that the Internet would allow them to efficiently reach any segment of customers that they wanted. And so the pragmatic founders of those startups went where the fishing was easiest — the customer segments (low-income consumers, young consumers, recent immigrants, etc.) that banks had been ignoring or underserving.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and you get to where we are today.

Banks, now legally and technologically unbound by geography, are going through a period of ferocious consolidation, in an effort to become as big as possible. And fintech companies, having plucked most of the low-hanging fruit that banks had been neglecting, are now moving up market and into new product categories, bringing them into direct competition with banks and other fintechs.

And this explains why the financial services organizations surveyed by BAI have ranked customer acquisition as one of their top challenges for the last few years.

Distribution advantages have disappeared. Competition has increased. And the fight to acquire new customers has never been more fierce.

But here’s the thing that we sometimes forget in the heat of battle — in financial services, not all customers are good customers.

When your product is money, your business is managing risk.

That risk can be credit risk (will my customer be able to pay me back?), fraud risk (will a criminal steal from me or my customers?), legal risk (will I get sued or fined for making a mistake with my customers’ money?), or reputation risk (will my brand get shredded for making a mistake with my customers’ money?)

You’re in the business of managing risk, which means that your enemy is adverse selection.

In economics, adverse selection occurs in a transaction between a buyer and a seller, when one party has more information than the other.

This information asymmetry shows up in all kinds of different places in financial services.

Take lending, for example. A common example of adverse selection is the discrepancy between what the borrower knows about themselves (who they are, what they are planning to use the money for, how capable they will be of repaying, how serious they will be about repaying, etc.) and what the lender knows about the borrower.

The purpose of loan underwriting is to shrink the information asymmetry gap between the lender and the borrower and reduce the lender’s odds of getting hurt by adverse selection.

The challenge is that if you are trying to grow, there is a natural tension within the customer acquisition process between marketing (convincing prospective customers to open an account) and underwriting (minimizing risk).

This is why financial services regulators are so suspicious of rapid growth and why they pay close attention to things like brokered deposits—if you are adding customers at a fast clip, you are likely doing so by reaching into new (and potentially risky) places and doing so aggressively (i.e. lowering your risk standards).

I’m also not a fan of rapid growth through traditional customer acquisition techniques, but not for the same reason.

My objection is strategic.

In a digital-first market, in which no company has an overwhelming distribution advantage, you can either get into a knife fight to grab new customers (and give all of your money to Credit Karma, Google, and Facebook in the process) or build products and brands that will entice the customers you most want to come to you.

That second strategy is the one that most banks and fintech companies should be leaning into.

You don’t want to acquire customers. You want to be acquired by customers.

The Power of Positive Selection

The term that I use to describe this strategy is positive selection, and once you learn to see it, you can’t unsee it.

The idea is that by building a product and a brand to appeal to a specific segment of customers, you can benefit from both the segment’s inherent characteristics and the behavioral characteristics that result from customers in that segment choosing to work with you.

Doctors are a great example.

Every financial services organization wants to serve doctors because of their obvious inherent characteristics. Doctors make a lot of money (the average salary for a U.S. physician in 2023 was $363,000). Doctors are always in demand and tend to have very stable career paths. Doctors rack up a lot of debt over the course of their professional lives (both personally and professionally). And doctors are notoriously sloppy payers, which creates ample opportunities to generate fee and revolving interest income.

Doctors are an appealing customer segment. The problem is that they know that.

So, if you try to acquire them through traditional channels, using the same generic horizontal products and branding that everyone else is using, the dimensions that you end up competing in — accessibility, price, convenience, etc. – create a race to the bottom.

Even if you win, you’re not acquiring a general cross-section of all doctors. You are negatively selecting for a subset of doctors with behavioral characteristics — risky, price-sensitive, fickle – that are the inverse of the competitive advantages that helped you win.

By contrast, if you build a compelling product and a brand that doctors will go out of their way to choose — not because it’s accessible, low-priced, or convenient, but because it’s the only one of its kind — then you are positively selecting for a subset of doctors with behavioral characteristics that reflect the utility of your product and the promise of your brand.

There are actually quite a few banks and fintech companies that have built (or acquired) products and brands designed to positively select for doctors, nurses, dentists, and veterinarians. KeyBank’s Laurel Road for Doctors, Fifth Third (through its acquisition of Provide), and Panacea (a digital bank for doctors) are all good examples.

Panacea, for instance, positively selects for doctors by offering what it calls PRN Loans, which are personal loans that are underwritten based on where the borrower is in their journey towards becoming a practicing physician (fourth-year students, residents and fellows, etc.), rather than solely on their credit score and debt-to-income ratio (which typically aren’t great when you’re first starting out). Panacea also offers access to a “primary care banker” who is trained specifically to understand the evolving needs of a doctor and is available 24×7 because, in Pancea’s words, “they work doctors’ hours, not bankers’ hours”.

The Challenge of Designing for Positive Selection

The trick with positive selection is that it’s often non-obvious and difficult to copy. It requires a unique insight into the segment that you are looking to serve and the product and brand features that will positively select for the most desirable customers within that segment.

In a recent article, Matt Brown at Matrix Partners, pointed to Afterpay as another good example:

Afterpay’s powerful insight was combining the best of several trends (ecommerce adoption, limited traditional credit use among younger consumers, etc) with a deliberate choice of customer segments (fashion and beauty) that reinforced its competitiveness in a space that was somewhere between excruciatingly competitive (consumer credit) and minimal (consumer credit for 18-36 year olds). By focusing on fashion and beauty – where buyers and sellers naturally had a high frequency of lower-value transactions – you could be more flexible in assessing and pricing risk (because the downside the low, especially if 25% was paid upfront) and have leverage in shaping consumer outcomes because you needed to be in good standing to continue using the network as a consumer.

Afterpay is a good example of a series of product choices that may seem odd from the outside, but are deliberate and powerful when viewed through the lens of the risk insight. Risk insights and secrets are, well, secrets. Some publicize them, but most successful companies don’t. And it can be even harder to discern what they are when they’re expressed in non-obvious ways.

I’ve found the deeper and more powerful a risk insight is, the more confusing its manifestations in product and marketing can initially seem. This can be an “ugly” product. Seemingly weird ICP or product messaging. Features that should be there but aren’t, or that seemingly shouldn’t be but are. That’s because the company isn’t oriented around a traditional and observable approach to company building, but around an insight into risk that manifests in non-obvious ways.

This non-obviousness is what makes it so dangerous to copycat … without understanding their risk insight and the series of interlocking product and marketing choices that amplify it.

Simply focusing on a specific affinity group or customer segment is insufficient if that selection doesn’t make you better off in risk in some way. The same applies for the multitude of companies that tried to do BNPL for different sectors. They copied what they could see superficially of Afterpay’s company and strategy, without understanding the foundational importance of customer selection and risk orientation.

As Matt points out, the most powerful insights into customer segmentation and risk orientation often manifest in confusing and unintuitive product and marketing decisions.

The reason for this is that positive selection requires building something that your desired customers will need to go out of their way to get. They have to proactively seek it out and work hard to acquire it.

If it’s too easy or too broadly appealing, the advantages of positive selection disappear.

But this, of course, is the problem. In financial services, we’ve convinced ourselves that banking products should always be beautiful, banking experiences should always be frictionless, and banking services should always be easily accessible.

This is why even when banks and fintech companies identify a good segment to go after, the end results rarely end up meeting (or exceeding) their expectations. It’s not the idea. It’s the assumptions we wrap around the idea.

Take Finn, the short-lived digital banking app from JPMorgan Chase, as an example.

The segment insight – younger consumers are an attractive market opportunity and aren’t well served by traditional banking products and experiences – was correct. It wasn’t a novel insight back in 2017, but it was broadly correct.

The problem with Finn was that it was built to appeal to what Chase executives assumed the generic young consumer would want out of a bank account — a streamlined, digitally-native experience that never requires a visit to the branch — which turned out to not be a good assumption. Here’s what Ron Shevlin wrote when Finn was closed down in 2019:

If Finn’s target market was “younger, digitally native users,” it was barking up the wrong tree. Just 7% of 20-something Millennials and 6% of 30-something Millennials said a digital bank would be in their consideration set. In contrast, 9% of Gen Xers and 7% of Boomers said they would consider a digital bank.

Why were Gen Xers and Boomers more likely to be interested in a digital bank than Millennials?

Well, because young people are more likely than middle-aged people to want in-person banking experiences:

According to J.D. Power’s 2023 US Retail Banking Satisfaction Study, customers’ widespread use of bank branches has grown to just under pre-pandemic levels as the U.S. and the rest of the world acclimate to doing things in person.

Almost three-quarters of customers surveyed say they plan to visit a branch at the same rate this year. Interestingly, 21% of customers under age 40 say they expect their branch visits to increase compared to 12% of those over 40. Those results come against a perception that younger bank customers are more likely to embrace a fully digital experience.

Wait, I hear you say, how can that be? That doesn’t make any sense!

Ahh, but it does.

Young people are inexperienced when it comes to money. They don’t know how it works. They don’t know what they should be doing. And they have plenty of free time to visit a branch or talk on the phone and get financial advice from a qualified professional.

By contrast, middle-aged people — and I now speak from personal experience here — have no free time. Zero. We know how money works (mostly), and we know what we want (mostly). What we need are automated, intelligent digital tools to help us do those things in the most convenient and low-touch way possible.

As unintuitive as it sounds, Finn by Chase would have had a greater chance of success in attracting and deeply engaging new Millennial customers if it had required them to come into the branch.

Positive selection is really freaking weird.

Opportunities to Design for Positive Selection

The good news is that because positive selection is such a weird and difficult-to-grok concept, there is plenty of white space left in financial services to build niche products and brands that profitable customers from underserved segments will want to acquire.

I’ll offer a couple of diverse examples, just to illustrate the true breadth of this opportunity.

Embedded Finance

I wrote about this last year. Compared to direct customer acquisition, which I simplistically described in my essay as “operating a money store”, indirect customer acquisition through embedded finance partnerships can deliver much less risky outcomes:

You are operating a money store. You know that everyone walking into your store is looking to buy money. You know that these prospective customers have hidden information that may give them an advantage over you. You have to efficiently expend your limited resources to uncover that hidden information and discover which of them you want to work with.

Allow me to propose an alternative.

What if you were selling money inside someone else’s store?

Now we’ve changed the equation. The denominator is different. The population of folks in your store isn’t made up of people looking to buy money. It’s made up of people looking to do something else entirely.

These folks still have an informational advantage over you. However, two things are different. First, the store that you are selling within has information on these prospective customers. Information entirely outside the realm of what direct financial services providers have access to. And second, the impact of that information asymmetry (which can never be fully eliminated) may be different because the underlying characteristics of the store’s population may be different. In other words, the store may have already positively selected for a segment of consumers that you would, all things being equal, prefer to work with.

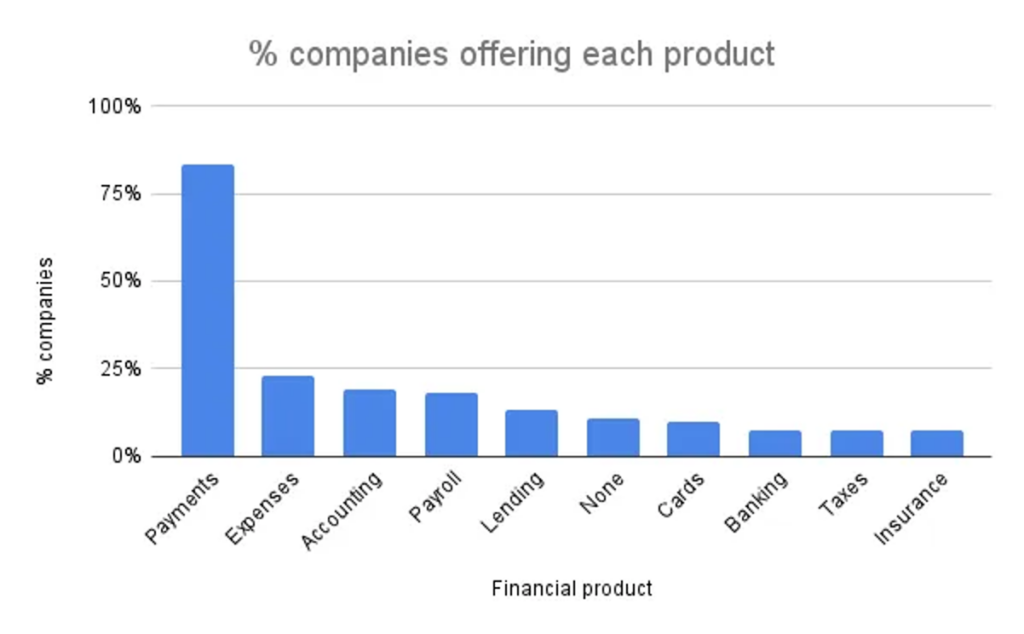

And as Matt Brown pointed out in an article about embedded finance in vertical SaaS, outside of payments, there’s still a lot of untapped opportunity for banks and fintech companies to harness the power of positive selection through embedded finance partnerships:

A Digital Bank for Teachers

I’ve been begging for someone to build this for years because A.) I have a soft spot for public school teachers, and B.) it’s a compelling business opportunity.

Credit risk professionals know that one of the most predictive pieces of information, when trying to assess a borrower’s likelihood to repay, is their profession. Profession tells you a lot. Obviously, it gives you a view into their current and future income. However, it also reveals a lot about their financial stability. Is this a profession that is always hiring? Do professionals in this field have a long average tenure? Are there macroeconomic forces that might impact the stability or demand for this profession in the near future?

The challenge is that U.S. lenders are not allowed to consider profession as a variable within their credit underwriting models because profession tends to be highly correlated with protected classes (gender, age, race, etc.) under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act.

That said, there is nothing prohibitive about building a product and a brand that positively selects for customers within a specific profession, as long as you don’t make having a job in that profession an explicit requirement for approving them for a loan.

As we’ve already covered, banks and fintech companies have long understood this opportunity when it comes to obviously attractive professions like healthcare (high income, stable job). However, it’s not as popular of a strategy when it comes to more subtly attractive professions like teaching (low income, stable job).

A Digital Bank for Digital Security Fanatics

This one is a bit more out there, but hear me out.

According to the FTC, consumers reported losing more than $10 billion to fraud in 2023, marking the first time that fraud losses have reached that benchmark, and representing a 14% increase over reported losses in 2022.

Two things about this stat:

- It’s almost assuredly underestimating the actual number, as only a small portion of fraud and scams are reported to the government.

- If the public furor over Zelle scams is any indication, banks and fintech companies will likely be forced to assume more liability for those losses, regardless of what Reg E says.

This should be alarming to banks and fintech companies.

We’ve given consumers a suite of digital financial tools that have made it extraordinarily easy for them to get ripped off by criminals. And as Tommy Nicholas, CEO of Alloy, wrote in a recent op-ed, generative AI is going to make things so much worse.

Given that, would it be crazy for a bank or fintech company to build a digital bank for consumers who are hyper-focused on digital security and protecting their personal information?

Positively selecting for this group would feel weird. Instead of a frictionless digital onboarding experience, you’d want to construct an experience that felt more akin to breaking into Fort Knox.

The friction would select for consumers who take digital security seriously, which would (in theory) manifest as fewer fraud losses for the financial services organization on the backend.

Get Acquired

Almost everything in financial services is trending in the same general direction—large, digital-centric, multi-product banks (and neobanks) that can efficiently serve a broad swath of consumers across multiple segments and verticals.

Everyone is trying to become JPMorgan Chase, basically.

I don’t like that strategy. Traditional customer acquisition only works if you have a natural advantage, like geography, or a synthetic advantage, like ZIRP-era VC profligacy, to fall back on. Those distribution advantages have (mostly) been wiped away, which means customer acquisition is now a game rigged in favor of the behemoths.

Instead, more banks and fintech companies should follow JPMC’s playbook from 2017. Finn didn’t work, but niche banking products and brands designed to drive positive selection can.