An oversimplified model of how banking has traditionally worked looks something like this:

- A bank invests in building a differentiated model for customer acquisition. It could be branches in a specific geographic area or TV commercials featuring celebrities. Whatever.

- This acquisition model enables the bank to acquire liabilities (i.e., deposits) and assets (i.e., loans) without competing solely on price.

- The bank invests a lot in risk management to ensure that they are pricing their assets and liabilities correctly and mashing them together in ways that will maximize profit (i.e., net interest margin) within acceptable risk parameters.

This model has worked exceptionally well for banks for a very long time. However, it rests on a critical assumption — banks will be able to acquire and (more importantly) retain their assets and liabilities without having to price them competitively.

Historically, this hasn’t been a problem.

For most of its lifespan, the U.S. banking market has been fractured, opaque, and time-consuming to traverse. The interest rates available to you were the ones that the local banks in your community offered. There was no way to quickly compare those rates to what other banks in other communities were offering. And moving your accounts from one bank to another was so painful that even if you found a bank offering you a better price, it was highly unlikely that you would dedicate the time and energy to switch.

This context is important because it helps us understand things like brokered deposits.

Quick review — in 1989, Congress enacted Section 29 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act to impose restrictions on brokered deposits in response to the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s. The idea was to restrict banks’ use of deposits that were sourced indirectly through third parties (i.e., deposit brokers), which in 1989 was understood primarily to be human brokers who would shop around large piles of cash from wealthy customers to banks around the country, which would compete to offer the highest interest rate (usually in the form of a certificate of deposit).

The rationale for the brokered deposit rules (which, you may have heard, are in the process of being updated, yet again) was informed by regulators’ experiences watching the S&L crisis unfold and is simple to understand from their perspective — banks that need brokered deposits are (likely) badly-run banks, and we should watch them carefully and restrict their use of brokered deposits if they get into trouble.

Brokered deposits were a proxy for risk.

This makes sense in the context of the 1980s, but it’s kinda bizarre to think about in the abstract.

Ohh, my God! This bank is paying its customers a competitive rate for their deposits! What the fuck are they doing? We gotta get in there and slow them down before they crash the financial industry!

It’s strange to think that the mere act of paying a depositor a competitive rate for their money in 1989 could be a sign that a bank was acting recklessly, but that’s because most of us today can’t fathom living in a world in which it was so hard, as a bank customer, to get a fair price.

In the 1980s, you literally had to pay someone to call a bunch of banks on the phone and haggle with them to get a fairly priced CD. Very few people had enough money to make this worth it, which meant that very little of the money that sat in banks in the 1980s was hot (i.e., likely to move quickly if offered a higher rate).

So, logically, Congress and bank regulators designed a system around the assumption that hot money = bad.

Here’s the interesting part — this is no longer a safe assumption.

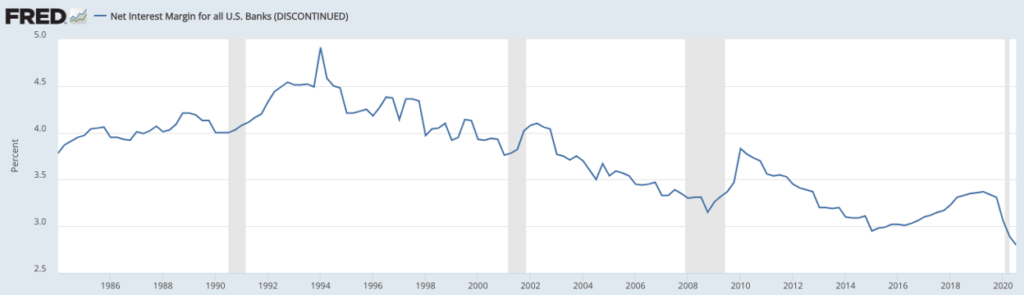

NIM Compression

Net interest margin (NIM) — the difference between what a bank pays for deposits and what it charges for loans — has been steadily declining at U.S. banks since 1994:

There are lots of reasons for this decline, but there are three specific ones that I want to highlight, all of which just so happened to crystallize in 1994:

- Interstate Banking — In 1994, President Clinton signed the Riegle–Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act into law. It allowed banks to branch across state lines and allowed bank holding companies to acquire banks in any state, regardless of state law.

- The Internet — In 1994, Tim Berners-Lee left CERN and founded the International World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the Mosaic web browser — one of the earliest web browsers, capable of multimedia browsing — became available across PC and Macintosh computers, and the number of web servers increased from 500 to more than 10,000, which helped get more than 10 million people online for the first time.

- Risk-based Pricing — In 1994, Signet Financial Corp spun off its wildly profitable credit card business into a monoline company, Capital One. Capital One pioneered the use of data analytics for risk-based pricing (i.e., individually evaluating and pricing the risk of each credit card customer rather than offering a single rate for all customers).

Interstate banking leveled the competitive playing field, allowing all U.S. banks to compete with each other. The internet supercharged this competition and made it significantly faster and easier for bank customers to open new accounts and move their money around. And risk-based pricing and data-driven customer segmentation enabled banks to compete on price at a more granular level (to the benefit of bank customers).

Over the last 30 years, shopping for the best price in banking has slowly transitioned from a luxury only available to the rich to a reasonable option available to the mass market.

That’s progress, but we’re still not as far along as we should be.

Despite having access to the information and digital tools necessary to efficiently chase rates, many bank customers still settle for suboptimal interest rates on their deposits. According to a Bankrate survey from earlier this month, the national average savings account yield was 0.61% APY.

And on the lending side, it’s the same story. During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when interest rates dropped to zero, only 5.2% of consumers refinanced their auto loans, and only 19% refinanced their mortgages.

Technology has made money hotter than it used to be, but it’s not uniformly scorching.

Not yet …

The Future of Money Will be Hot, By Default

Looking forward, there are two big changes that I think will have an enormous positive impact on the financial lives of bank customers and an enormous negative impact on the bottom lines of banks.

(Editor’s Note — The content for this essay section was inspired by the great Matt Harris at Bain Capital Ventures, who was the first person I saw tie these ideas together. Not shocking. Matt is one of the OG fintech brains. Check out this presentation he gave a while back for more details.)

The first is open banking.

Here is what Rohit Chopra, Director of the CFPB, said when he announced the draft rule for open banking last year at Money20/20 (emphasis mine):

American families can see the imbalance between them and their financial providers. As market interest rates have risen, many struggle to find credit cards and loans at affordable rates, and, yet the largest banks have not been paying those same families much more for their savings. Millions of families are being paid interest rates as low as 0.01 percent on their bank accounts, even though other institutions are offering rates that are way higher, even up to 5 percent.

This reflects the current reality that many banks design their products – sometimes purposely – so that it’s a hassle to switch, just like wireless phones used to be. On average, Americans have had the same checking account for 17 years. If switching were easier, American families could earn billions of dollars more in interest each year.

Today, the CFPB is proposing a rule to activate a dormant authority under a 2010 law to accelerate much-needed competition and decentralization in banking and consumer finance by making it easier to switch to a new provider. The Personal Financial Data Rights rule would help address many of the root causes of sticky banking – by giving people more power to walk away from bad service and enabling small community banks and nascent competitors to peel away customers through better products and services with more favorable rates.

The CFPB’s proposed Personal Financial Data Rights Rule, which is expected to be finalized within the next month or two, is explicitly designed to undermine banks’ ability to acquire and retain the suboptimally priced assets and liabilities that their net interest margins depend on.

Under this rule, financial services companies offering transaction products (checking, savings, credit cards, BNPL, digital wallets, and possibly EBT accounts) must share data on these accounts when their customers ask them to. That data will include things that banks have traditionally not shared and that they view as proprietary, such as pricing, rewards, and terms and conditions.

What this will mean, in practice, is that it will no longer be a secret to customers if they are getting suboptimal pricing or service from their banks.

Other banks will tell them in excruciating detail!

The impact on marketing will be huge. Imagine going from “Hey, you can save money if you switch over to our product” to “Your bank is ripping you off. Switch to our product, and you will save $570 a year”.

Whatever opacity that still exists in banking will be significantly reduced by open banking.

The second big change is generative AI.

As you know, generative AI is a field of artificial intelligence that uses massive unstructured data sets to train models to be able to generate new outputs that are probabilistically similar to their training data.

These models are constantly getting smarter (thanks to the massive amount of money that tech companies are pouring into them). We are fast approaching the point where they will be capable of acting as autonomous agents, performing generalized tasks on behalf of humans.

These AI agents might be a bit inexperienced and overeager (sometimes they will lie or get stuff wrong), but they will be relentless in their pursuit of optimal outcomes, and they will have a level of general intelligence and capability that we’ve never seen before.

How will consumers and companies use them?

They will use them to do things they can and should be doing today but are too lazy to do.

That has the potential to break a lot of business models that depend on laziness or uninformed decision-making, including net interest margin.

My favorite way to conceptualize what this will look like in banking is to picture little ‘rate optimization robots’ roaming around the market, working on our behalf, constantly trying to refinance our loans and increase our deposits APY.

When rates move, bank customers will move … instantly. Price discovery will become perfect, and product utilization will become fully optimized.

This should scare the shit out of banks and any bank regulatory agency not named the CFPB.

Thanks to the relentless march of technology, in the not-too-distant future, all money will be hot by default.

The Product Development Imperative

This presents a huge challenge for banks.

They’ve spent decades strengthening their risk management muscles in order to ensure that their NIM-centric business model doesn’t get tripped up by excessive interest rate, liquidity, or credit risk.

That’s great! Risk management is (and will continue to be) really important!

However, it won’t matter how good they are at risk management if banks can’t acquire and retain the suboptimally priced assets and liabilities their business model requires.

To avoid competing on price, banks will need to compete on value.

They will need to deliver products and experiences that cause customers to choose to work with them rather than constantly chasing after the best rates. Quite literally, banks will need to convince their customers to overrule the recommendations of their rate optimization robots.

Fortunately, I think this is possible.

Why Consumers and Small Business Owners Will Choose to Overpay

In his book The Innovator’s Solution, Clayton Christensen, the father of the theory of disruptive innovation, argues that in a mature market, where product performance is relatively equal across suppliers, the cheapest and most modular products win.

This is a very rational theory, and, in many cases (mainframe computers, aircraft engines, medical devices, etc.), it has proven to be entirely accurate.

However, as Ben Thompson noted in an excellent rebuttal to Christensen’s theory, while business buyers are usually rational, consumer buyers are not. Consumers usually don’t make product buying decisions by coldly comparing the costs against the speeds and feeds. They think differently:

The business buyer, famously, does not care about the user experience. They are not the user, and so items that change how a product feels or that eliminate small annoyances simply don’t make it into their rational decision making process.

[However] some consumers inherently know and value quality, look-and-feel, and attention to detail, and are willing to pay a premium that far exceeds the financial costs.

I think this is true in banking as well.

As technology continues to make it easier for banking customers to seek out the best pricing, we will see a divergence in the market.

Large enterprise customers will become even more rational about their financial services buying decisions in the future. Executives at these corporations will become increasingly nervous about overruling the recommendations of their procurement AI agents as the quality of these agents’ recommendations continues to improve.

(Editor’s Note — In the near future, there will absolutely be a securities fraud lawsuit in which an executive is asked why he ignored the recommendation of the company’s AI. You can take this prediction to the bank.)

On the other hand, consumers and small business owners (who tend to behave like consumers) will still be willing to make irrational decisions about which banking products they use, provided that banks give them a compelling reason to do so.

Any bank that wants to continue making money from net interest margin must figure out how to inspire such irrationality.

Inspiring Irrationality

Now, we end with the most important question — How do you build a banking product that consumers or small businesses will explicitly choose to pay more for?

This is a tough one.

Banking products are commodities. A checking account is a checking account is a checking account. They all offer the same basic functionality, and whenever someone comes up with a new bit of functionality (like 2-day early access to paychecks), it is quickly copied.

The product differentiation that banks need to strive for is more subtle.

Here’s Ben Thompson again, explaining how Apple differentiates itself from its smartphone competitors despite often having worse performance specs:

You see this time and again when it comes to iPhone differentiation, which focused on the actual experience, not numbers on a spec sheet:

- The iPhone has a superior touchscreen (which can only be felt, not bullet-pointed), but lower resolution than competing smartphones

- The iPhone has bigger pixels in its camera, but fewer of them relative to competing smartphones

- The iPhone has superior performance-per-watt, but fewer cores and lower clock speeds than competing smartphones

- The iPhone has superior battery life compared to a similarly-sized competing smartphone, or a much-smaller size compared to a competing smartphone with equivalent battery life

But how exactly does Apple do this? How are they so good at this subtle, experience-focused differentiation?

Trung Phan, who publishes a fabulous newsletter called SatPost, wrote an article last year that attempted to explain the important but difficult-to-pin-down idea of having good taste.

The article draws on quotes from two noted tastemakers — Steve Jobs and Rick Rubin — to explain precisely what taste is, how it can be cultivated, and the immense value it can provide in the product development process.

I wanted to call out two specific points from the article because I think they’re highly relevant to the challenge of building better banking products.

Let People Build What They Would Want

Taste is personal. The only way to build something great is to trust your own well-cultivated sense of taste and hope that others will get value out of it. Here’s a quote from Rubin:

Make something that speaks to [you]. And hopefully someone else will like it. But you can’t second-guess your own taste for what someone else is going to like. It won’t be good. We’re not smart enough to know what someone else will like.

To make something and say, ‘well, I don’t really like it but I think this group of people will like it’, I think [that approach] is a bad way to play the game of music or art. Do what’s personal to you, take it as far you can go.

In financial services, I think the best example of this is the “Built by X, for X” category of fintech products: the serial entrepreneur building the business bank account she always wanted or the doctor building the debt consolidation loan that he always thought should exist.

Not all of these fintech products end up turning into great businesses (most don’t, in fact), but the impulse — I understand what needs to get built here, and I’m going to solve this problem for others like me — is something that we need more of in financial services.

(Editor’s Note — My recent article “Acquire or Be Acquired?” covers this topic in much more detail if you want to dig deeper.)

Don’t Ship It Until It’s Right

Taste is also something that you can’t compromise on. If you rush something out the door, even though you know it’s not quite right, you compromise your taste. Here’s Jobs:

I don’t think my taste in aesthetics is that much different than a lot of other people’s. The difference is that I just get to be really stubborn about making things as good as we all know they can be. That’s the only difference.

It doesn’t take any more energy — and rarely does it take more money — to make it really great. All it takes is a little more time. Not that much more. And a willingness to do so, a willingness to persevere until it’s really great.

On the question of taste, this is where fintech often falls short. The desire to always be shipping is laudable, but when I look at many of the companies that like to brag about their product velocity, I frequently notice shoddy craftsmanship (and poor compliance).

Fintech companies that don’t just ship code to hit OKRs or blindly copy the latest fintech fads are, in my personal opinion, often the ones with the most subtly differentiated products.

Chime has always stood out to me in this respect.

Will Your Customers Choose You?

It’s easy to forget that most banking customers today aren’t explicitly and continually choosing to pay more for the financial products they use. They’re just defaulting to the path of least resistance.

Once technology flips that default, once customers’ money becomes programmatically hot, banks will learn just how little value they’ve been providing.

At that moment, risk management won’t be enough. Banks will need to build products that customers will fall deeply and irrationally in love with.