If you wanted to summarize the debate we’ve been having about earned wage access over the last eight years, it would go something like this:

Regulators and Consumer Advocates: Earned wage access is a loan.

EWA Providers and Fintech Trade Associations: No, it’s not.

Regulators and Consumer Advocates: Yes, it is. You’re giving people access to money and charging them for it. That’s a loan.

EWA Providers and Fintech Trade Associations: But none of our fees are mandatory, and we don’t try to collect if the customer defaults.

Regulators and Consumer Advocates: But most customers do pay a fee, so the fact that it’s not mandatory is irrelevant.

EWA Providers and Fintech Trade Associations: That doesn’t make any sense!

Regulators and Consumer Advocates: Your face doesn’t make any sense!

As you might be able to glean from the end of that fictionalized exchange, the debate has gotten a bit intense over the last year or so, at a state level and, more recently, at a federal level, with the CFPB’s proposed interpretive rule on earned wage access.

So, in today’s essay, I want to talk about the CFPB’s interpretive rule, the impact it will have on the market (if it ends up sticking around), and why the debate over earned wage access misses the point.

What does the CFPB’s proposed interpretive rule do?

Put simply, the CFPB is trying to make it clear that earned wage access products are loans under federal law.

In contrast to a 2020 advisory opinion from the CFPB, which stated that EWA products were not an extension of credit if they met several specific conditions, the bureau’s new rule takes a very broad view of what constitutes “credit” under the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) by defining “debt” to include any obligation to pay money at a future date, even if the amount is contingent on future events, such as the availability of funds from the next payroll event.

The rule applies to any product that involves both “the provision of funds to the consumer in an amount that is based, by estimate or otherwise, on the wages that the consumer has accrued in a given pay cycle” and “repayment to the third-party provider via some automatic means, like a scheduled payroll deduction or a preauthorized account debit, at or after the end of the pay cycle.”

Functionally, this means that the CFPB’s rule applies to both “little e” eWA products (i.e., those that are offered directly to consumers without any direct integration or sponsorship by the employer) as well as “big E” EWA products (i.e., those offered through employers).

(Editor’s Note — a tip of the hat to Kunal Kaul for the “little e/big E” framing, which I love.)

According to the CFPB, the optional fees commonly found in earned wage access products qualify as “conditions of the extension of credit” and must be disclosed as part of the finance charge. This includes both expedited delivery fees, which are common in both EWA and eWA, as well as tips, which I fucking loathe and are commonly found in eWA.

What will be the impact of the CFPB’s proposed interpretive rule?

It may not have any impact at all if the rule isn’t finalized or if it’s stopped through judicial intervention. The CFPB is almost certainly getting sued over it, and the lawyers I speak to tell me that the bureau’s case, on legal, policy, and administrative grounds, is not terribly strong (especially in a post-Chevron world). Plus, it seems highly possible that the clock may run out before this iteration of the CFPB can get the rule finalized, which would be a problem for them if November 5th doesn’t go the way they’re hoping.

However, let’s just say that the rule ends up sticking around in its current form. What would be the impact?

The TILA-mandated disclosure of the APR seems like it should be a big deal — the CFPB’s research found that the APR for a typical EWA loan is 109.5%, which is a large and scary-sounding number!

However, it’s unlikely that new disclosure requirements would be all that disruptive to the existing earned wage access market.

There are two reasons for this.

First, under TILA, an APR disclosure is not required if the close-ended loan is under $75 with a finance charge that does not exceed $5 or if the loan is more than $75 but the finance charge does not exceed $7.50. This exception would cover a large percentage of eWA and EWA loans.

Second, and more fundamentally, I don’t think astronomical-sounding APRs (if they were disclosed) would do much to dissuade consumers from using earned wage access products. I don’t think most consumers understand what an annual percentage rate is, nor how they should think about it as a point of comparison when shopping for credit (especially short-term, small-dollar credit). Consumers like earned wage access products, and from what I can tell, they don’t think that paying a couple of bucks to access their pay early is unfair or predatory (though I imagine at least some of them find the notion of tipping a fintech app to be as bizarre as I do, but I digress …)

The real impact of the CFPB’s interpretive rule would be to bring earned wage access products into the purview of state lending laws, many of which include caps on interest rates (36% is a common usury limit, though it varies from state to state). If eWA and EWA products are considered loans under TILA, then any of them that charge interest rates above the usury limits in states that align their lending laws with TILA would become illegal (except those products that are offered through national banks, which would be able to preempt state restrictions).

This would be a big deal for the earned wage access industry. Most providers are not nationally chartered banks, nor are they partnered with such banks, which means their product would suddenly become unavailable in large portions of the country.

One possible result of this change would be the elimination of all voluntary fees from eWA and EWA products, which would allow them to continue to be offered in states with TILA-aligned interest rate caps (you can call it a loan, but if the finance charge is zero you can’t call it usurious).

My question is what happens if that happens? If earned wage access products can’t charge fees to consumers and if employers continue to be reluctant to pay for EWA as a benefit for their employees (as the vast majority are today), who will offer these products? And why?

This brings us to the essential truth that the current eWA/EWA debate ignores.

EWA isn’t a Loan. It’s Data.

eWA — the direct-to-consumer, not-integrated-with-employers type — that’s a loan. These products use consumer-permissioned cash flow data to get a rough estimate of how much money a consumer has coming to them, which they then use to underwrite small-dollar cash advances against those future paychecks.

Dave, the neobank, is a good example. It offers a cash advance product called ExtraCash, which provides customers up to $500. There is no interest and no late fees, but Dave does charge a fee for expedited delivery, and it does (embarrassingly) ask for tips.

It’s a relatively safe and customer-friendly product, as short-term small-dollar loan products go. But it’s absolutely a loan. Dave reported a 2% 28-day delinquency rate for its ExtraCash portfolio in Q2 of 2024.

EWA — the employer-sponsored and integrated type — is fundamentally different. The risk of delinquency and default is near zero because EWA isn’t a loan product. EWA is a method for more accurately calculating the true balance of a customer’s bank account.

The product doesn’t guess how much a fast food worker is likely to have earned in their current pay cycle and use that insight to underwrite the risk of a loan. The product knows how much that fast food worker has earned in their current pay cycle because the EWA provider is directly integrated into the fast food restaurant’s time and attendance system. This allows the EWA provider to make those funds available to the employee early without taking on any credit risk.

They are simply showing the customer how much money they actually have.

This is a subtle but highly compelling idea.

One of my favorite features of Simple (the OG neobank founded in 2009) was its safe-to-spend balance, which allowed users to see how much money they had in their accounts minus their expected monthly expenses.

The reason I liked it so much was that it recognized an essential truth — the question, “How much money do I have in my bank account?” is more complex and context-dependent than a traditional bank ledger would suggest.

You can create a great deal of utility for consumers by providing a more comprehensive and intelligent answer to that question.

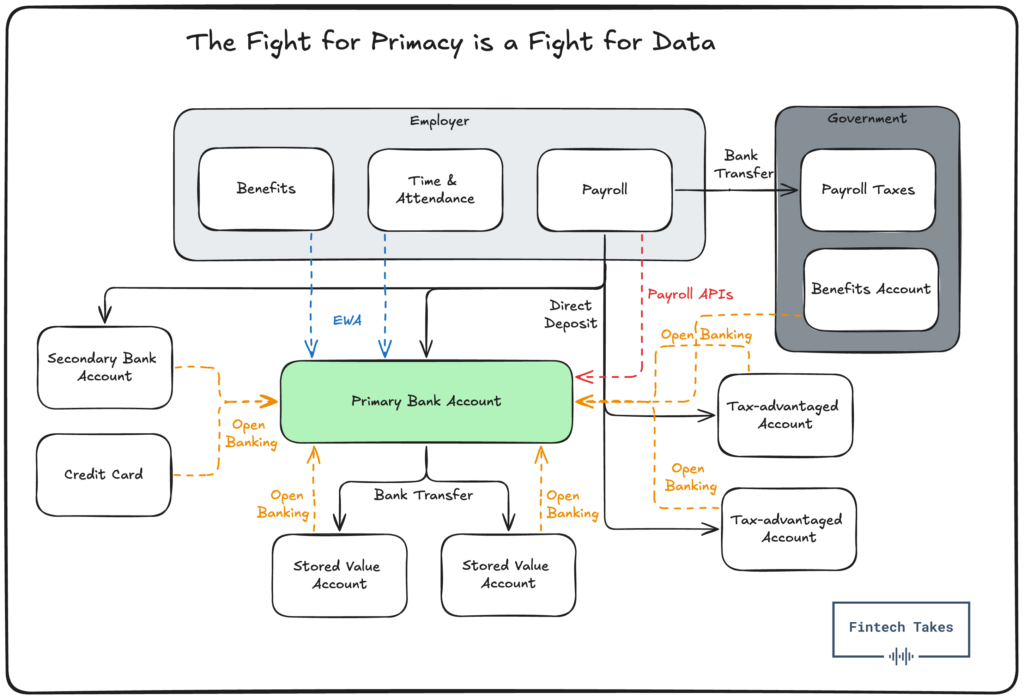

Indeed, I believe that the banks that acquire and retain the most primary bank account relationships in the future will be those that acquire the data necessary to answer that question in the most complete and helpful way possible.

You can see little glimpses of this future in the market today, if you know where to look:

- Two-day early access to paychecks is a feature that is enabled by capturing a consumer’s direct deposit and using the ACH file from the employer to give the bank the confidence to float the money in advance of the funds settling.

- The ability to tap into FSA/HSA or EBT funds for eligible expenses (or expense reimbursements) in real-time (see Bilt’s recent product announcement for an example) is enabled through open banking integrations that tell the bank how much money is in consumers’ government benefit and tax-advantaged accounts.

- Integrations with credit card issuers (or, in the near future, via open banking) allow banks and digital wallet providers (like Google) to help consumers improve how they earn and redeem their rewards at the point of sale.

- Consumers can now even optimize their tax withholding on a paycheck-by-paycheck basis through integrations into payroll systems and some clever engineering from companies like April.

- And, of course, EWA provides a unique level of visibility into previously untouched systems within employers’ HR and Finance stacks, including time & attendance and benefits.

All of these products and product features are small moves in a larger game; a game that many market participants don’t yet perceive or understand — the fight for data about how much money customers actually have.

The Fight for Data

So, to return to our earlier question — why would a financial services provider choose to offer EWA, even though they may be severely constrained in their options to directly monetize that product?

Because EWA (and the direct integrations with employers it leads to) unlocks data that makes bank accounts more useful. It literally puts more money in customers’ accounts, with no credit risk.

This is why I believe that “big E” EWA will continue to be a viable product category for banks and fintech companies, even if the CFPB’s proposed interpretive rule ends up being finalized in its current form.

This is why I believe that Chime, which helped pioneer two-day early access to paychecks as a feature in consumer bank accounts, acquired Salt Labs, an employee savings, rewards, and benefits platform.

And this is why I believe that the CFPB, which wants to ensure that this fight for data doesn’t create new competitive moats for the winners, is likely to prioritize consumer-permissioned access to payroll data as a top priority for version 2.0 of its Personal Financial Data Rights rule (i.e., open banking) after the initial rule is finalized later this year.