Up to this point, open banking in the U.S. has been a game that anyone could play, but that no one had to play.

This is what I have generally referred to as the “market-driven era of open banking.” And I use that terminology because, at the end of the day, open banking in the U.S. exists because U.S. consumers demand it. By sharing their financial data with authorized third parties, consumers have been able to access better financial products, prices, and experiences.

In this era, fintech companies — focused on gaining market share from incumbents — were the primary users of consumer-permissioned financial data, and banks and credit unions — focused on defending their market share against incumbents — were the primary (often reluctant) suppliers of it.

In this era, innovation flourished and consumers benefited, but the playing field wasn’t level and the experience wasn’t always smooth.

Now that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has released the final version of the Personal Financial Data Rights Rule (commonly known as Section 1033), the game has changed.

By securing strong consumer financial data rights, the CFPB has transformed open banking in the U.S. into a game that everyone has to play, whether they want to or not.

From a policy perspective, there are two reasons why I think the CFPB believes this shift is important for the market.

First, if everyone plays, it creates a smoother and more reliable experience for everyone.

Screen scraping powered the first phase of open banking in the U.S. However, over the past few years, the industry and regulators have driven a shift towards “developer interfaces” (i.e., APIs). The consensus in the market is that APIs are the gold standard if your goal is to create a comprehensive and highly performant consumer-permissioned data infrastructure for financial services providers to build on top of.

The final version of the CFPB’s rule, which mandates financial services providers to stand up developer interfaces and to ensure that those interfaces meet minimum performance requirements, will go a long way in solidifying open banking as reliable infrastructure in the U.S., giving greater confidence to both developers and consumers.

Second, if everyone plays, it will make the game fairer and more competitive.

Under the final rule, every company that offers covered financial accounts (deposit accounts, credit cards, digital wallets, and pay-in-4 BNPL) will need to provide their customers’ data to authorized third parties at their customers’ request (with the exception of banks and credit unions with $850 million or less in assets, which are exempt). These companies are referred to in the rule as “data providers,” and this requirement will meaningfully strengthen data coverage for open banking in the U.S. by ensuring that no data provider prevents or limits authorized 1033 data sharing.

Additionally, the rule will likely motivate certain market participants who may not have fully embraced the benefits of open banking to finally go on offense and become what the rule refers to as “data recipients.” This is certainly the intention that the CFPB has, as Director Chopra explained when the draft rule was released a year ago:

The business opportunity is about how you can steal the lunch of your bigger competitors — that is going to be key … You cannot look at open banking as a compliance burden only — you have to look at it as a business opportunity too.

It’s imperative that smaller financial service providers pursue this opportunity aggressively because bigger providers aren’t waiting to go on offense, as this quote from Bill Demchak, CEO of PNC, highlights:

“We’ll pull share out of smaller banks who won’t have the technology to be able to take advantage of open banks,” Demchak said.

Regulators are “doing this because they think they’re going to lower switching costs,” he said. “All they’re going to do is drain [small] banks of accounts, by big banks who have the technology.”

Put simply, in the new era of open banking that we are about to enter, every financial services company will need to be prepared to be both a data provider and a data recipient.

This is exciting!

However, it will also be a bit chaotic and difficult to navigate, at least for the next few years. It reminds me a bit of the fun-but-confusing scene in Top Gun: Maverick, where Maverick has the other pilots playing dogfight football, in which the teams play offense and defense at the same time.

We’re all playing offense and defense at the same time now. And having a plan for how your company will comply with the final rule’s compliance requirements (for both data recipients and data providers) and develop a strategy for capitalizing on the benefits of open banking in this new era is essential.

The purpose of today’s essay is to provide some insights to help inform that plan. I will walk through the compliance deadlines and key requirements for data recipients and data providers, and offer some ideas on the best path forward for each group.

Let’s start by talking about the compliance deadlines.

Compliance Deadlines

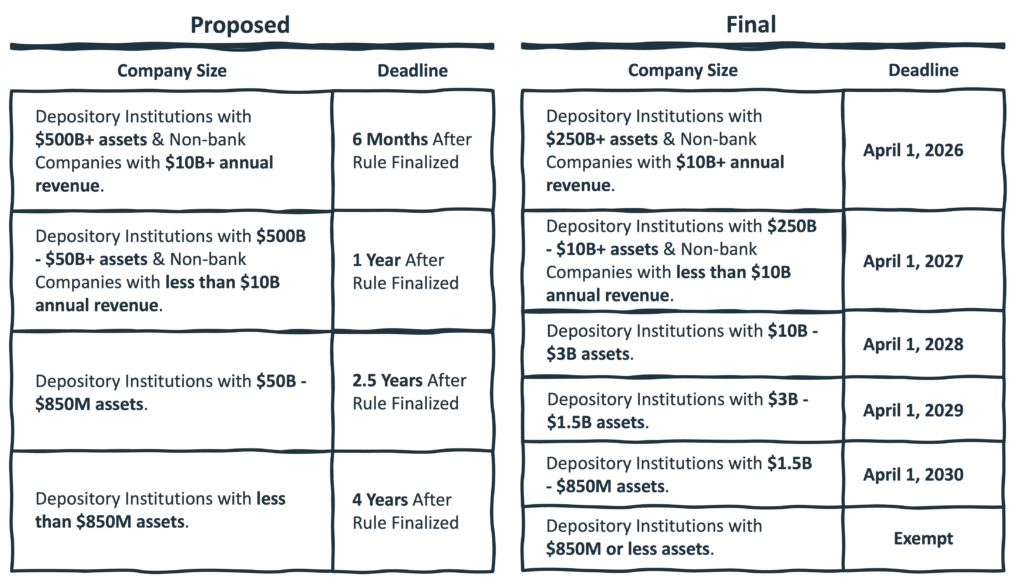

One big change from the proposed rule to the final rule is the deadlines for when data providers need to be in compliance.

The CFPB received A LOT of feedback from the industry that the proposed deadlines were too tight, and in response, the bureau pushed the dates back and created a more granular compliance schedule for data providers of different sizes.

Here’s a summary of the changes:

As you can see, everyone got more time, with a particularly big break for banks and credit unions under $10 billion in assets. Additionally, at their urging, banks and credit unions with $850 million or less in assets were exempted entirely from the requirement to stand up a developer interface.

(Editor’s Note — For what it’s worth, I think community banks and credit unions with $850 million or less in assets made a mistake in pushing to be exempt in the final rule. Open banking is a competitive necessity in the U.S. Many community banks and credit unions have already stood up developer interfaces and are exploring how to add value as data recipients. Read this recent American Banker OpEd for a more fleshed-out version of this argument.)

The rationale for these changes boils down, primarily, to two considerations: 1.) The CFPB has yet to designate an official standard-setting organization for consumer-permissioned financial data sharing in the U.S. (read more about that here), and it’s hard to build a developer interface when you don’t know what technical standards you need to build to, and 2.) The technical lift to set up a developer interface will be significant for smaller data providers, many of which will be dependent on third-party technology vendors.

Interestingly, it’s a bit unclear in the final rule what the compliance deadline is for data recipients (i.e. those companies that the consumer authorizes to access their financial data).

My best read of the rule is that data recipients should be in compliance with the rule by the same deadlines as the data providers they are receiving data from. Practically speaking, this means that the compliance deadline for data recipients is April 1, 2026 (i.e., the date that large data providers like JPMorgan Chase must be in compliance).

But what exactly are the compliance obligations of data recipients under the finalized Personal Financial Data Rights Rule?

GREAT question!

What Data Recipients Need to Know

A data recipient is any company that receives authorization from a consumer to access their financial data in order to provide them with a product or service.

Today, most data recipients are fintech companies and other non-bank financial service providers that leverage open banking to streamline experiences or deliver new products and services. Picture a personal financial management app using transaction data to help a consumer budget or a non-bank lender using cash flow data to underwrite a consumer for a loan.

However, as we’ve already discussed, forward-thinking banks and credit unions are beginning to aggressively utilize consumer-permissioned data sharing to increase their own competitive differentiation and gain market share. I expect many more financial institutions will become data recipients under the Personal Financial Data Rights Rule in the next few years.

For data recipients, the final rule requires them to focus on three key things:

- Authorization Management

- Record Retention

- Onboarding

Let’s take a second to talk through each of these.

Authorization Management

Under the final rule, data recipients are required to capture the consumer’s authorization for accessing their financial data. This is actually a very big deal and was the subject of intense disagreement between banks and fintech companies during the comment period for the proposed rule.

The CFPB’s rationale for requiring the data recipient (rather than the data provider) to capture the consumer’s authorization is that the data recipient is in the best position to understand what covered data is reasonably necessary for providing the product or service that the consumer has requested and that allowing the data provider to play a significant role in the authorization process could create friction and impair access to authorized consumer data.

However, under the final rule, the data recipient is required to make some very specific disclosures to the consumer when getting their authorization. This includes disclosing the precise scope of the data necessary for the use case that the consumer is authorizing (e.g., a routing and account number for a pay-by-bank use case).

This level of granular transparency during the initial authorization process is new and is a direct result of the CFPB’s focus on limiting any secondary, unrelated uses of the consumer’s data.

And it’s not just the initial authorization that needs to be captured anymore, either!

Under the final rule, data recipients will need to capture the consumer’s reauthorization for the use of their data for many persistent use cases (e.g., budgeting) no less than once every 12 months.

This has the potential to be an added point of friction between data recipients and their customers (this is why card networks and issuers invented card account updaters to automatically update account numbers for card-on-file use cases). However, I expect we will see significant investment in the ecosystem to reduce or eliminate this friction moving forward, building on the work that companies have already done to help consumers when their data connections break (Plaid’s Update Mode functionality is a good example).

Finally, the rule requires that consumers be allowed to revoke access to their data at any time. Interestingly, the rule provides a lot of flexibility for where and how a consumer can revoke access. It can happen directly through the data recipient, through a different third party (like a data aggregator), or through the data provider that is supplying the data (provided, of course, that the data provider enables this functionality in a reasonable manner that doesn’t interfere with the authorized data recipient).

Record Retention

The final rule also requires data recipients to establish and maintain policies and procedures for compliance and to retain records that can be used to demonstrate their compliance. This includes a copy of the signed authorization disclosure by the consumer as well as a record of all the actions taken by the consumer (including through a data provider or a different third party) to revoke the data recipient’s access to their data.

Onboarding

The last big bucket of compliance tasks under the final rule is probably the one data recipients think about the least, but that is the most important to data providers — onboarding.

As I wrote after the final rule was released, data providers (i.e., banks) are very concerned about how they will manage the risks of sharing data with third parties authorized by consumers. This is a fair concern, especially given the size and diversity of the fintech market in the U.S., and the CFPB adjusted the final rule to give more specific guidance to data providers on this front.

Under the final rule, a data provider is allowed to deny access to an authorized data recipient based on specific, well-articulated risk management concerns relating to data security, safety and soundness, or any other applicable law regarding risk management. Additionally, access may be denied if the data recipient fails to give the data provider essential data about itself, including its legal name, website URL, legal entity identifier, or contact information.

Based on these guidelines, there are two things relating to onboarding that data recipients should keep in mind:

- You need to be prepared to provide all of the required information on your business and your data security and compliance processes and procedures to any data providers that you want to access data through.

- Data provider processes and timelines will vary tremendously from one data provider to another, especially in the early days of implementing the rule.

What Data Providers Need to Know

A data provider is any company (bank or non-bank) that provides covered accounts (deposit accounts, credit cards, digital wallets, or pay-in-4 BNPL) to consumers.

Data providers’ responsibilities under the final Personal Financial Data Rights Rule mirror, in many ways, the responsibilities of data recipients that we just reviewed.

Data providers must make covered data available at consumers’ direction through a safe and reliable developer interface that meets specific performance requirements, and that adheres to designated industry standard specifications.

As I already mentioned, we don’t yet have an officially designated standard-setting organization for consumer-permissioned financial data sharing under the final rule (although I expect we will soon … and my money is still on the Financial Data Exchange). And while many of the larger banks, credit unions, and fintechs in the U.S. have already built their own developer interfaces for consumer-permissioned data sharing (and negotiated individual data access agreements with open banking platforms and larger data recipients), there is a very long tail of smaller banks, credit unions, and fintechs that still need to do this work.

Under the final rule, data providers are required to retain authorization (and re-authorization) records, and they have the option to provide consumers with a way to revoke authorization.

And as we already discussed, data providers are required under the final rule to onboard new authorized data recipients in a timely and unbiased manner while taking appropriate steps to assess and mitigate safety and soundness and data security risks.

The Need for Centralized Facilitation

There are two reasons why it’s important to think about the compliance requirements for data recipients and the compliance requirements for data providers as two sides of the same coin.

First, as we’ve already discussed, it seems highly likely that most financial services companies in the U.S. will eventually end up playing both roles.

The final rule requires that any company that provides covered accounts (except banks and credit unions with $850 million or less in assets) must comply with the rule as a data provider. And the competitive imperatives to use open banking to acquire and retain customers (or risk big banks taking them from you) suggest to me that most financial services providers will eventually become data recipients as well.

Second, there is a big need for centralized facilitation in open banking in the U.S.

The U.S. financial services industry is massive. Unlike the highly concentrated markets of our friends in the UK, Australia, and Canada, the U.S. has tens of thousands of banks, credit unions, and fintech companies.

From a competitive perspective, that’s wonderful. Consumers benefit when they have more choices.

However, when it comes to creating an open banking ecosystem that is compliant, fair, and low-risk, the size and diversity of the U.S. market become huge impediments.

How, for example, are data recipients and data providers supposed to keep track of consumer authorizations, re-authorizations, and revocations and remain synchronized on which data they are allowed to share/use/hold, especially given how likely today’s consumers are to have multiple bank/credit union/fintech relationships at the same time?

Or, to use another example, how can we expect data providers to individually onboard tens of thousands of authorized data recipients in a timely and unbiased manner while effectively managing risk?

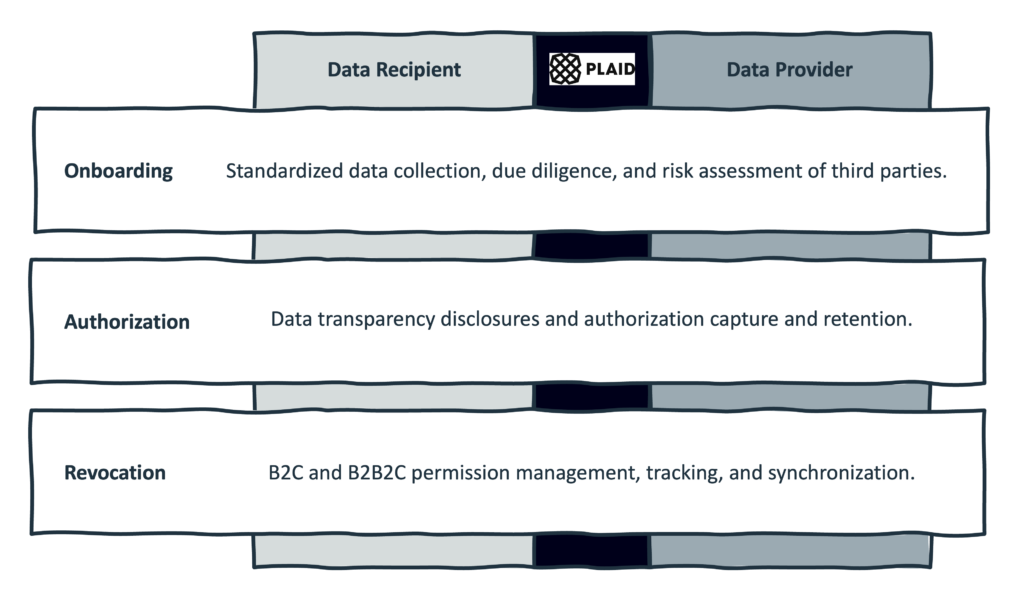

This is where I expect open banking platforms to play an important role. By being central nodes within a large and diverse network, these platforms can facilitate common and required tasks for both data providers and data recipients, which can help solve this coordination problem.

Plaid, which has done a lot of work to help data recipients and data providers comply with many of the requirements in the final Personal Financial Data Rights Rule (watch their recent 1033 Compliance Tech Talk for more details), provides an illustrative example of what this centralized facilitation model can look like:

No Time to Waste

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that there is a certain amount of uncertainty right now regarding the Personal Financial Data Rights Rule.

If you’ve been reading the newsletter recently, you likely know that shortly after the final rule was announced, a group of big banks (represented by the Bank Policy Institute) sued the CFPB to stop the rule.

Additionally, you may have heard that we had an election recently, the outcome of which will lead to some significant changes to the leadership and priorities of the CFPB next year.

The question is, what effect will these events have on the rule, and how should potential data providers and recipients price in the risk of uncertainty associated with these changes?

I’m not a lawyer, and my ability to forecast political futures seems to have significantly degraded over the last ten years (along with everyone else). That said, my advice to banks, credit unions, open banking platforms, and fintechs is to proceed as if nothing will significantly change.

Unlike other recent initiatives at the CFPB, the bureau took its time on open banking and, from my perspective, produced a final rule that is reasonably solid on policy and administrative grounds. I would be surprised if the BPI lawsuit succeeded in stopping it.

Indeed, I don’t think banks should want to stop it! Moving the industry, en masse, away from screen scraping and to developer interfaces is good for banks. It’s where the industry is headed already because it’s good for privacy, good for security, and good for performance and usability. The rule will just help us get there faster and more fairly.

And while I think new leadership at the CFPB will lead to lots of changes for the industry, open banking seems to be one of the few issues where there is broad, bipartisan support. The idea that consumers’ financial data belongs to them is no longer a serious point of debate and I think there is general agreement on the need for common standards and regulations governing the sharing of it.

Bottom line — we have entered a new era of open banking and we’re not going back. All financial services companies in the U.S. need to prepare to play offense and defense at the same time. And they need to start preparing now.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Plaid.

Plaid is a global data network that powers the tools millions of people rely on to live a healthier financial life. Our ambition is to facilitate a more inclusive, competitive, and mutually beneficial financial system by simplifying payments, revolutionizing lending, and leading the fight against fraud. Plaid works with thousands of companies including fintechs like Venmo and SoFi, several of the Fortune 500, and many of the largest banks to empower people with more choice and control over how they manage their money. Headquartered in San Francisco, Plaid’s network spans over 12,000 institutions across the US, Canada, UK and Europe.