At a press conference last week, Fed Chair Jerome Powell was asked if he would step down if President-elect Donald Trump (who has been critical of Powell and the Fed in the past) asked him to.

Here was Powell’s response:

This was heartening for those of us who believe in the importance of the Federal Reserve’s political independence (and in the importance of trust in institutions in general). However, it also made me wonder how the macroeconomic environment will evolve over the next four years.

While the Fed has begun to slowly lower interest rates this year, it’s not crazy to imagine them stopping or reversing that process if the impacts of President-elect Trump’s economic policies (broad-based tariffs in particular) prove to be inflationary, as many economists predict.

Speaking strictly from a fintech perspective, I don’t think this would be a bad outcome.

As frequent readers of this newsletter likely know, I’m not a big fan of the effect that low interest rates have on the fintech ecosystem. When rates are low (as they were in the lead-up to and immediate aftermath of the pandemic), money floods into the private market, looking for yield. This overinvestment tends to attract the wrong types of fintech founders and the wrong types of bank partners, and ordinary people get hurt.

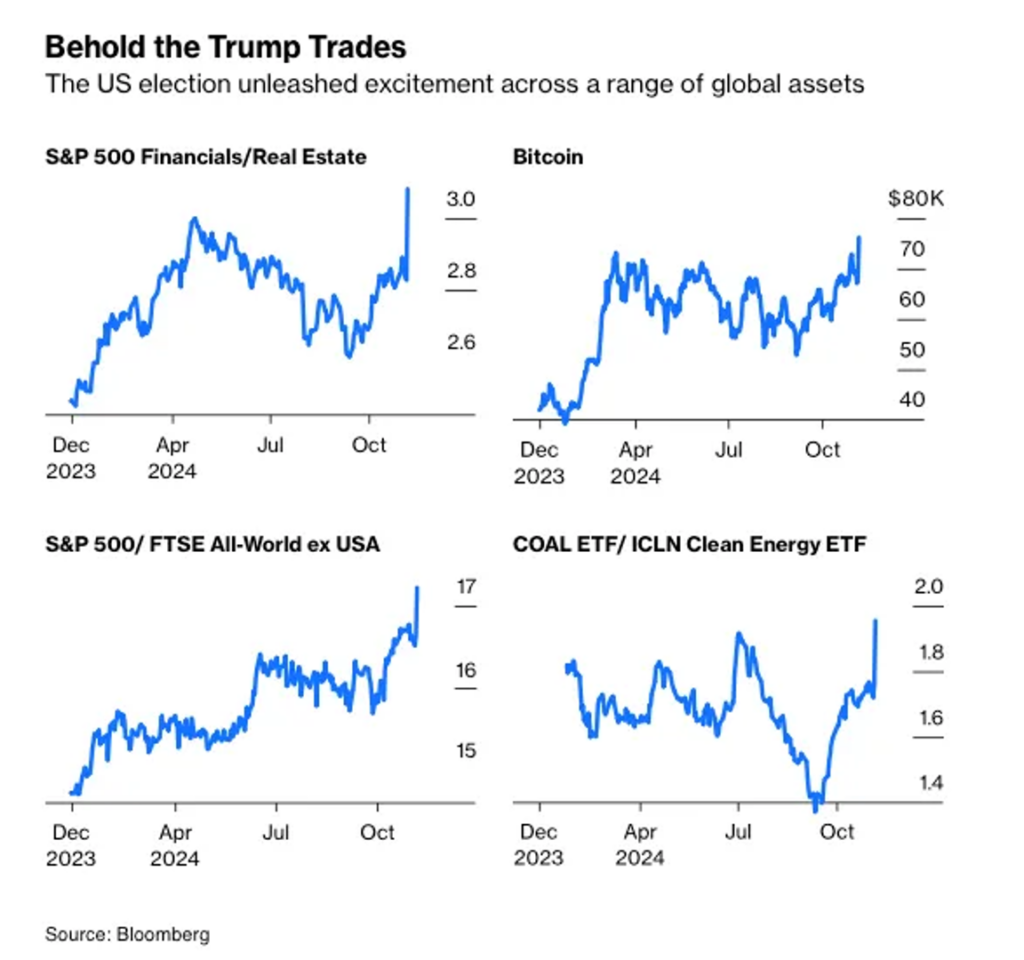

Unfortunately, regardless of where interest rates go from here, it seems likely that we are headed for a return visit to the manic days of 2021. The market’s enthusiasm for Donald Trump’s win suggests that another bubble is coming:

Bubbles!

Packy McCormick, VC investor and author of the Not Boring newsletter, published an essay earlier this week making the positive case for a Trump bubble. His analysis was based on a recently published book — Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation — by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber.

Packy writes:

Bubbles pull the future forward by concentrating tremendous amounts of financial and human capital on very specific visions of the future, and allowing for otherwise-wasteful exploration and parallelization in the pursuit of making it a reality.

Things that may not have happened – ever – without a bubble, happen rapidly with them.

This type of bubble — an inflection bubble, to use Hobart and Huber’s terminology — is different from your ordinary market bubble (like the one that crashed the global economy in 2007). Inflection bubbles are typically organized around a definite and constrained goal.

To Packy’s credit, he pauses briefly in his essay to consider if President-elect Trump’s Make America Great Again vision actually fits the definition of an inflection bubble:

Just making everything better, Making America Great Again, is too vague and imprecise to fit the book’s definition: “Crucially, this vision involves a concrete and actionable plan to transition from the present to the future.”

Build an atomic bomb before the Germans (or Soviets) is definite and constrained.

Get to the Moon by the end of the decade is definite and constrained.

Each of the bubbles Byrne and Tobias cover is definite and constrained.

But the Trump Bubble? A bubble in what, exactly?

Packy then answers his own question by framing the Trump bubble as a mission to make the U.S. Government more efficient and less burdened by unnecessary bureaucracy, which will (in Packy’s view) unleash an unprecedented wave of innovation and prosperity.

The first manifestation of this vision is President-elect Trump’s newly-announced Department of Government Efficiency, co-led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, which will be focused on cutting $2 trillion in government spending, and which President-elect Trump claimed could “become, potentially, ‘The Manhattan Project’ of our time.”

Rumspringa

In some senses, I agree with Packy’s argument.

There are lots of areas where excessive (and perhaps ideologically motivated) regulations are needlessly inhibiting needed progress. Housing and clean energy infrastructure are two examples that come to mind, and when you compare a heavily regulated state like California to a more loosely regulated state like Texas in those areas, the results speak clearly.

However, the problem with making deregulation the goal, in and of itself, rather than harnessing deregulation for some more definite and constrained goal, is that it risks unleashing collateral damage that outweighs the benefits that a more narrowly tailored approach to deregulation could also accomplish.

This, of course, isn’t a concern for VC investors like Packy. As he says in his essay:

The newly elected government is promising to cut through the cruft and get back to the sense of freedom and adventure that make the country great, even if it means breaking some things on the way. Like any good bubble, it’s risk-on.

And he’s not alone. The reason that the market is up in the wake of Donald Trump’s win is that investors of every stripe are similarly excited about the financial opportunities that can be unleashed by across-the-board deregulation. Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal uses a very apt analogy to describe this excitement:

Across a range of industries right now, it feels like investors are betting on Rumspringa, the rite of passage for Amish youth where the rules go away for awhile. Crypto rules, M&A rules, carbon emissions rules… For all of them, people seem to be betting that regulation will just go away, served up with lower taxes and maybe more stimulus. From the perspective of the financial asset holder, what’s not to love? At least for right now?

That’s it, exactly. This isn’t an inflection bubble. We’re not investing an outrageous amount of money into a unifying and aspirational goal like landing a man on the moon within a decade. We’re just tossing out the rules for four years.

And we should be honest about that because there will be a price that needs to be paid, and it won’t be Elon Musk or Vivek Ramaswamy paying it.

Building in a Bear Market

Crypto, as it frequently does, provides a useful example here.

Despite the vociferous claims by crypto advocates to the contrary, the last four years have been great for the crypto industry. Falling prices and cooling investor sentiment caused a stampede of unserious people to exit the industry (many of them rushed to AI). The most ridiculous and unsustainable fads in crypto (like NFTs and DAOs) burned themselves out. And what we were left with were serious founders and clear-eyed incumbents who saw crypto as a technology with the potential to solve real-world problems.

Stripe, which was early to crypto in 2014, actually got out of the crypto business in 2018, saying that Bitcoin was “better suited to being an asset than a means of exchange.” However, it got back into it in a big way with its recent acquisition of Bridge for $1.1 billion:

Bridge describes itself as the Stripe of crypto, specializing in making it easier for businesses to accept stablecoin payments without having to directly deal in digital tokens. Stablecoins are a type of cryptocurrency whose value is pegged to the value of a real-world asset like the U.S. dollar. Customers include Coinbase and SpaceX.

“It’s a sign that Stripe is serious about stablecoins and crypto,” Ahn said. “Payments were the original use case for crypto, and it’s finally here.”

Serious crypto businesses like Bridge quietly thrived under a Biden administration that crypto advocates believed was deadset on destroying them. And smart incumbents — Stripe, Visa, PayPal, JPMorgan Chase — never took their eyes off crypto use cases with real-world utility like stablecoins, despite crypto asset prices stagnating.

That’s weird!

It’s almost as if the crypto advocates who so despised SEC Chair Gary Gensler and who threw ridiculous amounts of money into the 2024 election cycle (to the peril of incumbent politicians like Senate Banking Chair Sherrod Brown) had some other motivation in mind.

Well, now they’ve gotten their wish:

By itself, this doesn’t really bother me. People (and special interest groups) have been supporting politicians with the hopes of enriching themselves for as long as politics has been a thing. And investors (both professional and retail) should be free to be as risk-on as they want to be.

What bothers me is that this unrestrained surge in optimism, combined with a ferocious focus on deregulation, will lead to the development of infrastructure that cause people to get hurt.

I call this infrastructure speculation-as-a-service.

Speculation-as-a-Service

When Robinhood was ripping, in the halcyon days of 2021, it perfected a business model that I coined speculation-as-a-service:

Robinhood customers engage with the app at a rate that is on par for most social media companies and utterly unheard of in financial services.

The trick, which Robinhood has mastered, is figuring out a way to package that engagement into a service that it can sell. I call it ‘Speculation-as-a-Service’, but you probably know it by a different name — Payment for Order Flow (PFOF).

When the meme stock craze burned itself out, and the crypto market crashed, Robinhood had to find new ways to sustain itself. This was when it added boring-but-proven products like retirement accounts and a credit card.

I thought these were very positive developments for Robinhood and, crucially, for the financial health of Robinhood’s customers.

However, I always had this feeling that Robinhood couldn’t wait to get back to its roots in speculation-as-a-service as soon as market conditions allowed. In related news, this post-election tweet from Robinhood’s CEO caught my eye:

This tweet is very much in keeping with the post-election excitement I’ve seen online from folks in tech and finance. And I can certainly see the upside in operating a casino that allows retail investors to speculate across these different asset classes.

What’s less clear to me, however, is why enabling even more expansive opportunities to gamble is in the best interests of Robinhood’s customers.

And in case you think Robinhood is a one-off example, consider a newly funded seed-stage startup BetHog, which is trying to build the world’s largest crypto casino and sportsbook.

Mike Dudas, a VC investor focused on crypto who led BetHog’s seed round, tweeted that he was excited about the investment as it was the “right team, right time, right product”:

It certainly does seem to be the right team (these guys founded FanDuel) and the right time (Trump bubble!), but why is it the right product? What is the virtue of a crypto-native casino and sportsbook in a world already overrun with online gambling?

If you’re BetHog or its investors, the answer is obvious — if you believe that more and more folks are going to invest in crypto (which seems like a guarantee over the next four years at least), it makes all the sense in the world to build a more seamless way for those investors to spend any gains from those investments on “entertainment.”

However, again, I fail to see the long-term benefit to the end customers.

And if you think that any losses that those end customers suffer are their own fault and of no concern to society at large, you should consider the emerging evidence of the socialized costs of gambling.

From a recent Bloomberg article:

Nearly one out of every three Brazilians lives below the poverty line. And poverty amplifies the desire to make an instantaneous fortune betting on the hometown soccer team or spinning the virtual roulette wheel. A recent central bank report underscored the magnitude of this problem and sent shockwaves through Brasilia: 20% of the money the government handed out for its flagship social program in August was spent at on-line gambling sites.

And an even more disturbing piece of evidence, courtesy of The Atlantic:

A recent paper, from the University of Oregon economists Kyutaro Matsuzawa and Emily Arnesen, shows another, perhaps more surprising—and certainly more harrowing—harm of gambling legalization: domestic violence. Earlier research found that an NFL home team’s upset loss causes a 10 percent increase in reported incidents of men being violent toward their partner. Matsuzawa and Arnesen extend this, finding that in states where sports betting is legal, the effect is even bigger. They estimate that legal sports betting leads to a roughly 9 percent increase in intimate-partner violence.

Please Build Responsibly

Look, I get it. Bubbles are fun. And I do agree with Packy that they can sometimes be productive for society.

That said, we just saw the effects that unrestrained mania can have on the product and business development priorities of fintech and crypto founders, and it wasn’t great!

Regular people got hurt.

And that was when investors’ enthusiasm (fueled by ZIRP) was balanced out by an aggressive (sometimes overly aggressive) regulatory apparatus. Once that apparatus has been dismantled, I shudder to think what such unrestrained mania will produce.

So here’s my plea to anyone building in fintech or crypto over the next four years — please build responsibly.