Embedded lending (delivering a loan in the context of the transaction that the borrower is trying to complete) usually wins over direct lending (requiring a borrower to proactively seek out a loan) because most borrowers value convenience in lending above everything else.

A loan is a means to an end, not an end in and of itself. You don’t get a mortgage because you want a mortgage. You get a mortgage because you want a house. Embedded lending offers a faster and more convenient path toward the outcomes borrowers want, which is why they almost always choose it.

Here’s how embedded lending emerges:

- New distribution infrastructure is built. It could be a mail-order catalog, a retail store, or an e-commerce platform.

- An embedded loan product is created to facilitate transactions within that new distribution channel. The loan product’s design is tailored to make the customer’s experience of transacting within that channel as convenient as possible.

- The success of that product attracts competition. Once the new loan product gains traction, copycats emerge, and lending volume in the product category shifts from direct to embedded.

The last century of financial services history is littered with examples of this pattern playing itself out, in lending and in other financial product categories — from the emergence of auto insurance in the 1930s (Allstate started as an add-on to tires sold in the Sears Catalog) to the growth of retail co-brand credit cards in the 1980s (cue Sears again, which launched the Discover Card through its stores in 1985) to the invention of indirect auto lending in the early 2000s (Dealertrack and RouteOne were created to connect car dealerships to a network of lenders) to the rise of pay-in-4 BNPL (facilitated through e-commerce platforms) over the last 15 years.

And it’s not just consumer financial services.

There is a massive opportunity for embedded lending for small businesses.

Why Embedded Small Business Lending Makes Sense

A thing that you hear over and over about small business owners (and what will deeply resonate with you if you’ve ever been a small business owner) is that they just want to focus on their craft. They started their business so that they could do what they love to do (make pizza, tutor 8th graders, practice law, repair cars, etc.), not be buried under an endless list of unfun administrative tasks.

Unfortunately, the administrative work is a part of the job for small business owners (at least until they get big enough to hire finance and ops folks to handle it), but they will go to great lengths to minimize the amount of time and mental energy they spend on it, which means that they tend to prefer to work with software systems and tools that can handle as many of the administrative jobs-to-be-done (JTBD) …

… In one place.

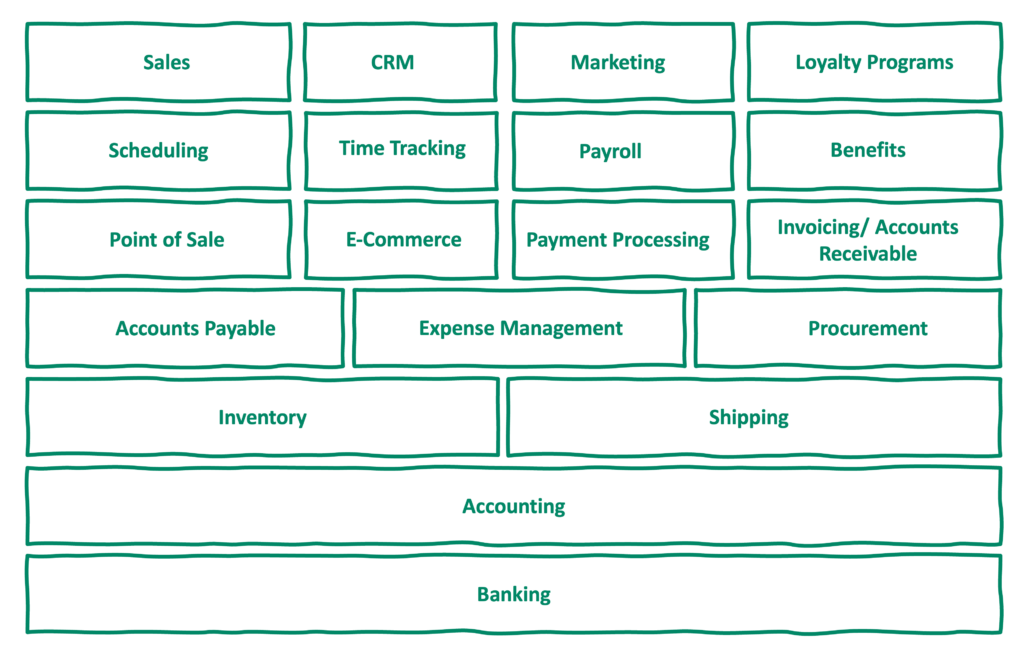

I call these software systems and tools Small Business Operating Systems (SBOSs).

There are many SBOSs in the market today, all having grown out of specific wedge products focused on different JTBD. Intuit Quickbooks (accounting), Square (point-of-sale payments), and Shopify (e-commerce) are all good examples:

And the success of these companies reveals another truth about small businesses — they are exceedingly difficult to acquire.

As of July 2024, there were more than 34 million small businesses in the U.S., according to the Small Business Administration. Most have an incredibly short lifespan (8.5 years is the average), and unlike consumers, they don’t all hang out in the same places, which makes them very difficult to target using traditional outbound marketing channels and techniques.

This difficulty means that established SBOSs like Intuit and Square have a tremendous advantage over their smaller competitors because their well-known brands act as magnets for inbound leads (i.e., if you are starting a small business, your first instinct is to go to an Intuit or a Square). Additionally, the breadth of their product offerings (which, remember, is highly appealing to small business owners) allows them to maximize their LTV:CAC ratio.

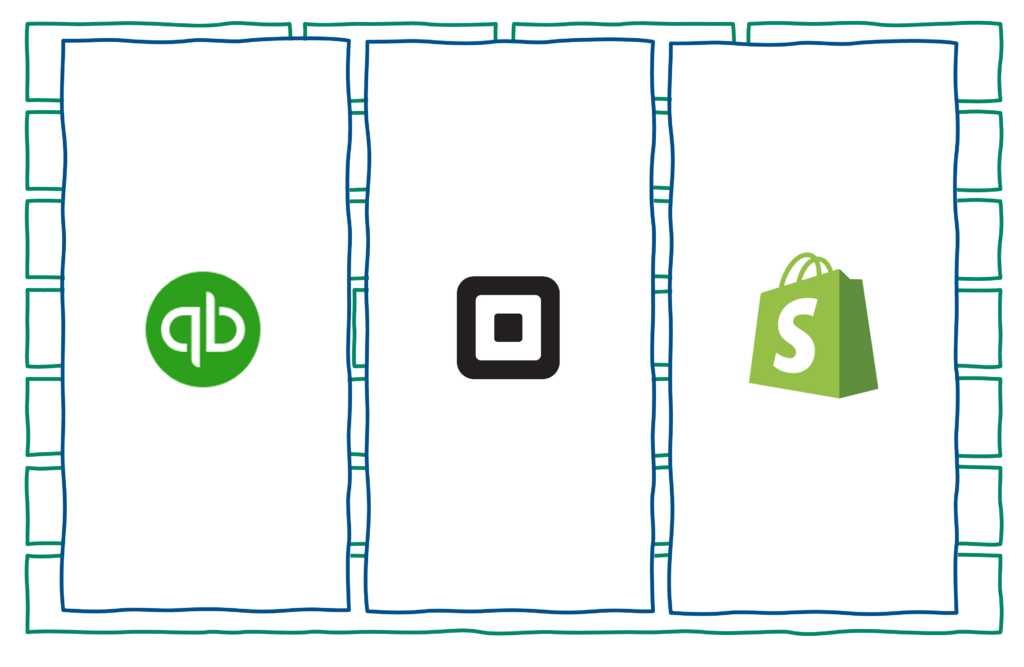

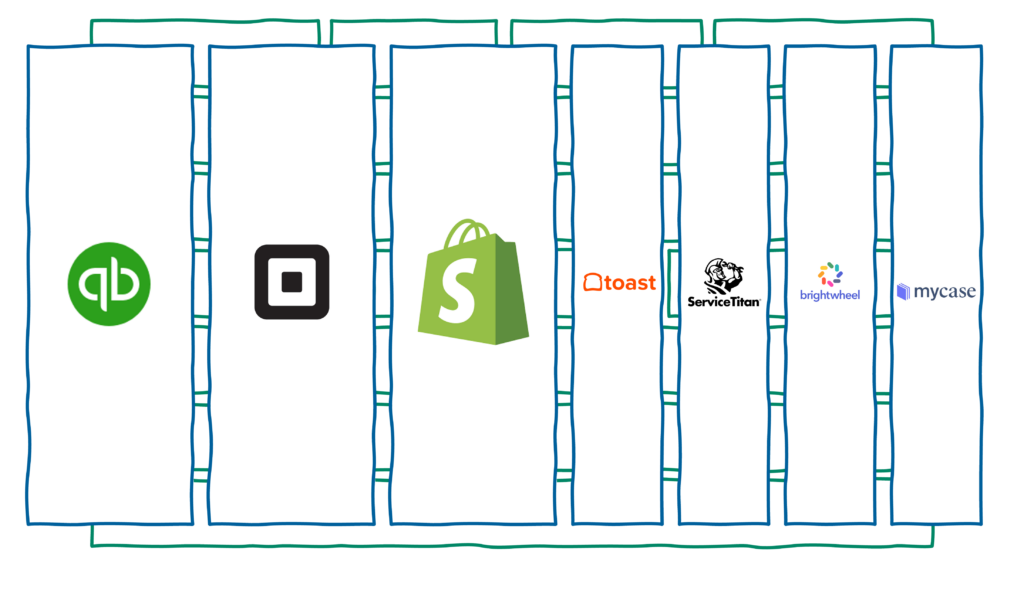

The only viable path to competing with these established SBOSs (at least that I have seen) is to build more vertically-focused alternatives.

I have written about this class of company — sometimes referred to as vertical B2B SaaS platforms — a lot, and for good reason. Their success has demonstrated that a more focused Small Business Operating System, designed to handle all of the specific eccentricities of a particular industry (e.g., restaurants, field services, childcare, legal services, etc.), can overcome the brand awareness advantages of their larger industry-agnostic competitors.

What a platform like Brightwheel (an SBOS for childcare providers) lacks in broad-based brand awareness, it more than makes up for in specific product features tailored to the needs of preschools (e.g., integrated curriculum development, digital admissions, etc.), which drives high NPS scores and word-of-mouth marketing. And like Intuit and Square, these vertically-focused SBOSs solve for a large number of JTBD for small business owners, allowing them to achieve similarly high LTV:CAC ratios.

So, this is the competitive landscape for small business customer acquisition.

Industry-agnostic SBOSs with a massive brand awareness advantage, complimented by a rapidly proliferating group of vertically-focused competitors relying on product-led growth.

The question is, how do you break into this picture if you offer a more focused or specialized product or service for small businesses? Like lending, for example?

You embed it!

Embedded distribution is a picture-perfect fit for small business lending.

Small business owners are already using SBOSs to manage their businesses. They are accustomed to getting everything through those systems. They have no desire to take time away from pizza making/tutoring/lawyering/car repair to go to a bank or non-bank lender and apply for a loan. And those lenders would prefer not to spend an arm and a leg acquiring their borrowers.

Everybody wins!

Additionally, small business lending has a significant underwriting advantage over direct small business lending because of the proprietary first-party data that SBOSs have on their customers.

Information asymmetry — the difference between what the two parties in a transaction know — is a fundamental challenge in lending, and in small business lending, that challenge cuts deeply both ways.

For the lender, it’s always likely that the small business owner knows something about the viability of her business and the competitive environment in which it operates that would make lending to her unacceptably risky, like, for example, if a new preschool is about to open in her community and siphon away 40% of her business.

And for the small business owner, it’s nearly impossible for any lender to see her business with the same clarity with which she sees it. This isn’t surprising. The lenders aren’t living in the business, day in and day out. They’re not talking to customers or suppliers. They’re not executing marketing campaigns or restocking inventory. So it’s not surprising that lenders don’t understand small businesses as well as their owners do, but it can be quite frustrating for those owners when they see opportunities to grow their businesses and lenders won’t give them the capital they need to seize those opportunities.

Small Business Operating Systems can reduce information asymmetry in small business lending. They have real-time, on-the-ground insights into the challenges and opportunities facing their customers because their customers use their software to run their businesses. The SBOS is the system processing payments, reconciling accounts, managing inventories, and running payrolls. It is a shared ledger of the small business’s reality!

“OK, OK,” I hear you saying. “That all sounds great in theory, but if this embedded finance pattern was playing out in this space, wouldn’t there already be some dominant embedded small business lending product we could point to as a success story?”

Why yes.

Yes, there would be.

Embedded Merchant Cash Advance

Square launched Square Capital, its small business lending arm, in 2014. Its primary offering is a merchant cash advance (MCA) product.

Square didn’t invent MCA. The idea of advancing a small business’ money against its expected future revenue has been around for a very long time. However, Square’s innovation was to embed this MCA product within its platform, making it available only to merchants that use Square to process payments. This provided the company with two key advantages:

- Embedded MCA is straightforward for Square to underwrite because Square already has all the data it needs. It can see the merchant’s historical sales activity (processed through Square), which enables it to model (with a high degree of accuracy) its future payment volume and volatility. This also creates a very seamless borrowing experience for the merchant (no lengthy application or need to submit a bunch of documentation).

- Repayment is collected directly from the daily sales processed by Square’s system, significantly reducing the risk of default. It also provides financial flexibility to the borrower because their repayment amount is dynamically tied to their sales volume.

Square Capital offers advances as low as $100 and as high as $350,000. Square charges a fixed, predetermined fee for borrowing the funds, and payments are based on a fixed percentage of a merchant’s daily Square-processed sales. There is no incentive for early repayment, and the maximum repayment term is 18 months.

Square Capital has been a phenomenally successful product, having advanced more than $9 billion to 460,000 Square merchants over the last 10 years.

In fact, it has (along with PayPal’s embedded MCA product that was launched in 2013) been so successful that it has inspired many of its competitors to launch similar products (Shopify in 2016, Stripe and Toast in 2019, etc.) as well spurring the development of embedded small business lending infrastructure (from providers such as Fundbox, Stripe, Adyen, OatFi, and Pipe) to enable other SBOSs to quickly launch their own embedded MCA products.

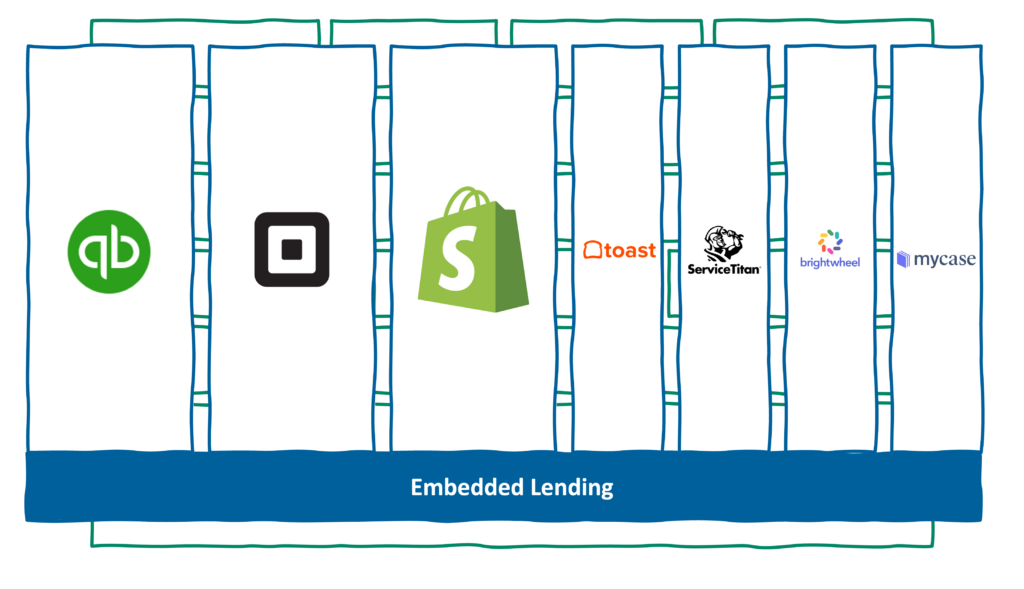

And this brings us to today, where we are at an interesting inflection point.

We have the distribution infrastructure necessary to enable embedded small business lending. We have a product construct (embedded MCA) that has clearly achieved product-market fit. And we have the lending infrastructure necessary to democratize access to this product construct broadly across the small business ecosystem.

So, we’re all done, right?

Well, if we were talking about consumer auto lending, we would be.

Once we nailed PMF for embedded (i.e., indirect) auto finance, it caught on like wildfire with car dealerships and consumers and grew to roughly 70% market share. There was no need to continue innovating on the product side.

However, as I am fond of saying around here, small business lending is MUCH more difficult than consumer lending.

Embedded finance might be the answer to our distribution problem in small business lending, but we still have a product problem, and embedded MCA (as great as it is) can’t solve it alone.

Small Business Lending is a Multi-Dimensional Product Problem

So, why doesn’t embedded MCA work well for all small businesses in all circumstances?

There are a few reasons.

First, while sole proprietorships and very small businesses (think 2-20 people) value convenience and flexibility, larger small businesses (which hire dedicated finance and ops folks) value certainty and control.

Embedded MCA is convenient and flexible (as we’ve discussed), but it doesn’t provide control (you can’t adjust the terms, and you don’t get any benefit from paying off the advance early) or certainty (you can’t be sure exactly how much your payments will be because it’s based on a percentage of daily sales).

Second, not all businesses require their customers to buy goods and services from them instantly at the point of sale, which means that not all businesses have the real-time payment streams necessary to power embedded MCA.

In fact, most small businesses (roughly 60-70%) are B2B businesses rather than B2C businesses, which means that they are far more likely to charge their customers via invoices (typically payable net 30/60/90 days) than they are to process payments from them in real-time through a point-of-sale system.

Third, and most importantly, the amount and form of capital that small businesses need to thrive extends far beyond what embedded MCA can, by itself, deliver.

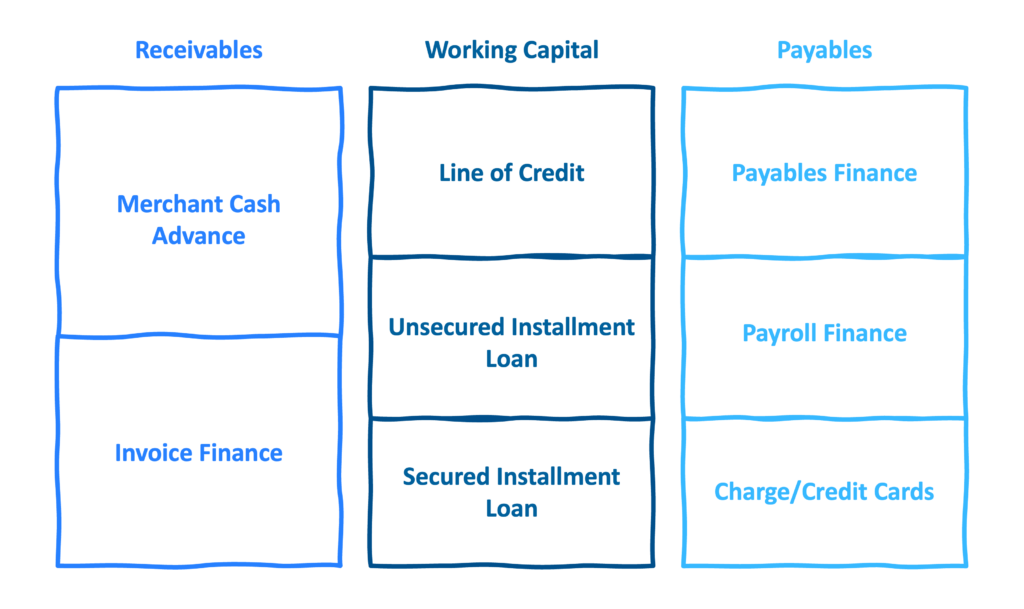

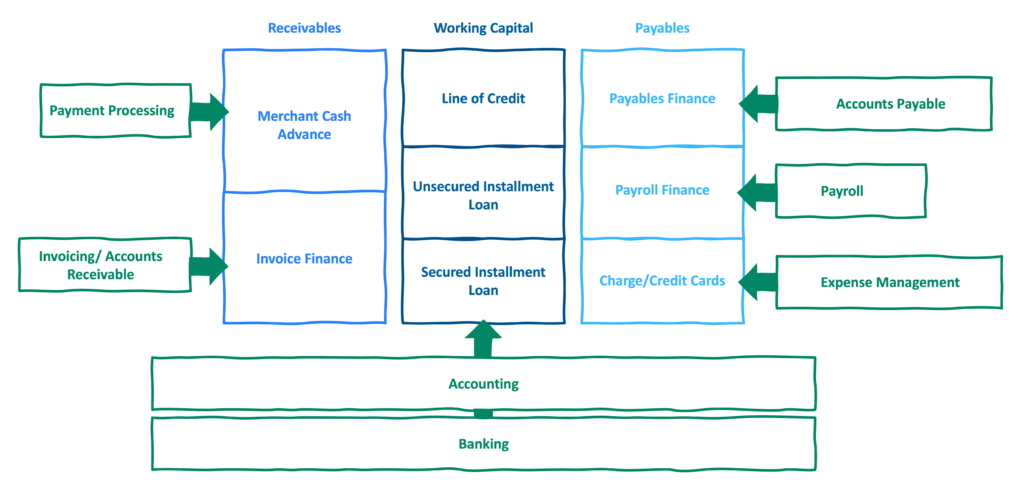

Here’s an easy way to think about it — every business has money coming in (receivables), money on hand (working capital), and money going out (payables).

Merchant cash advance is one way to accelerate money coming in. Invoice finance (sometimes called invoice factoring) is another way. It works roughly the same way that MCA works, but the underwriting is based on a B2B small business’s outstanding invoices (and the credit and fraud risk of its business customers).

For payables, obviously, the goal is the opposite — to slow the money down. This can be achieved through payables finance, in which a lender will pay a specific bill or invoice for a small business immediately and then allow the business to pay them back later. It also includes payroll finance (similar to payables finance, but focused specifically on underwriting payroll advances) and corporate charge and credit cards (which give businesses a flexible tool to buy stuff while extending out the payment).

(Editor’s Note — B2B BNPL has been a bit of a trend in fintech over the last couple of years. Depending on which party the B2B BNPL provider charges a fee to, it can be thought of as a version of receivables finance, payables finance, or both.)

Receivables finance and payables finance are usually expensive (because the buyer or seller on the other end of the transaction also really wants their money!), but, in some ways, they are easier to underwrite because they are often tied to a specific and measurable asset (e.g., POS payments, invoices, etc.)

Working capital finance, on the other hand, is much less certain. Whether it’s a line of credit, an unsecured installment loan, or a secured installment loan (real estate, equipment, etc.), this form of financing is much more difficult to underwrite because it’s not about patching temporary holes in a small business’s cash flow. It’s about answering a more fundamental question — Will this small business owner be able to successfully invest the capital I give them to grow their business?

Together, these categories of lending products make up what I like to think of as the Small Business Lending Stack.

To be clear — all of these products have already been built. For example, Fundbox partnered with FreshBooks to build an invoice finance offering over 10 years ago.

The big opportunity we have is to embed them, more seamlessly and more comprehensively, into the operating systems that small business owners rely on. We’ve made some progress toward this goal (especially for MCA), but we have a lot more to do, and I want to wrap up today’s essay by sharing a few insights into how we can enable that greater level of integration.

Embedded Lending Benefits From Depth

Many examples of embedded small business lending that you see in the market today are built on a very surface-level integration. The SBOS adds a tab called “Capital” and when the small business customer clicks on it, they are presented with an embedded loan application.

This experience is slightly more convenient than direct small business lending, but only slightly.

We can do better.

If you think of small business loans not as standalone products but as extensions of existing workflows, they can be integrated into operating systems far more deeply, thus creating a far more streamlined experience for customers.

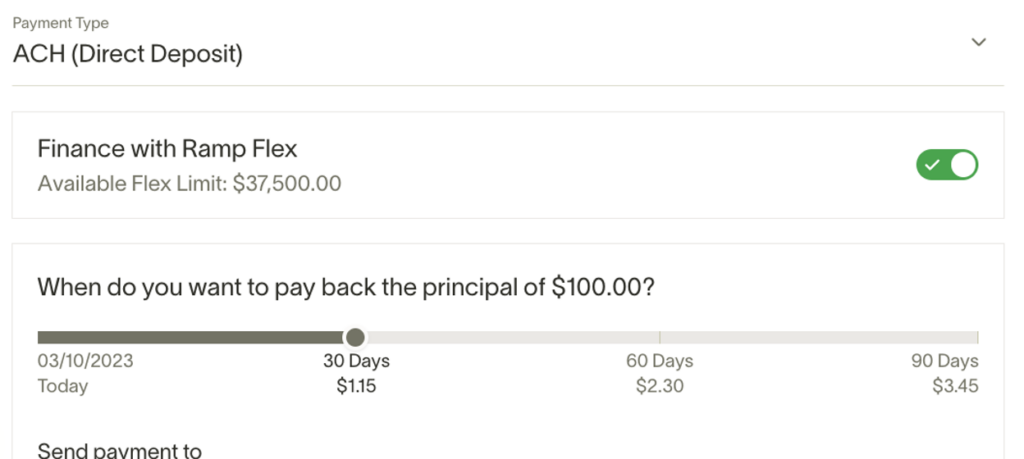

Ramp provides a good example. It offers a feature called Flex, which is a payables finance product. However, the neat part is that Ramp Flex (which I’m sure took quite a bit of work to stand up) is simply a feature within the company’s Accounts Payable product. Literally, it’s just a payment option that you toggle on when you are paying bills in Ramp.

This is what well-designed embedded small business lending looks like.

Embedded Lending Benefits From Data

Our goal is to make every lending product that a small business needs as accessible to them as Square has made its MCA product to Square merchants.

This means we need data.

Specifically, we need the proprietary data that is most useful for each small business lending product that we want to enable.

Merchant cash advance requires payments data. Invoice finance requires accounts receivables data (or, ideally, data from an all-in-one contract-to-payments system like Agree). Payables finance requires accounts payables and bill pay data (as in the Ramp Flex example). Payroll finance requires payroll data. Corporate charge cards and credit cards work much better (as providers like Ramp and Brex have discovered) when they can be underwritten and managed using data from an expense management system. Working capital installment loans and lines of credit require all of the above, plus bank account and accounting data (a good example of this is the line of credit offering that Fundbox built with Intuit for QuickBooks).

Fortunately, Small Business Operating Systems (both the industry-agnostic ones like Quickbooks and the vertically-focused ones like Brightwheel) already include many of the systems that generate this data. And it’s becoming increasingly easy for SBOSs to add additional point solutions like payroll to their offerings thanks to the new embedded offerings from providers like Gusto.

Embedded Lending Benefits From Nuance

As helpful as all this data is, it must be paired with a nuanced understanding of the differences between different types of small businesses.

Here’s an example — a law firm will usually have both an operating bank account and a trust bank account. When underwriting a law firm for a working capital loan, a lender might reasonably assume that it would be best to use the data from both accounts when underwriting the loan (after all, more money in the bank = higher odds of being approved). However, this would be a catastrophically bad mistake to make because law firms are legally prohibited from directly benefiting, in any way, from the money held in trust accounts on behalf of their clients.

Only a company that is experienced in serving law firms would understand this nuanced but very important point, which is why I am generally more bullish on the prospects of vertically-focused Small Business Operating Systems than I am on their industry-agnostic peers.

It’s also why it’s extremely important for SBOSs to partner with lending infrastructure providers and banks who appreciate the value of nuance and will work with them to tailor the design of their embedded lending products to account for it.

The Dream

Everything I have described so far is very achievable (and is, in fact, being built right now). So, let’s end with a vision of the future that is a little further out (but still achievable):

In the future, Small Business Operating Systems will be able to assemble — across all the jobs-to-be-done that they do for their customers — a comprehensive data profile of each of their customers, which can be used to underwrite the business for credit, holistically.

The small business owner never applies for anything. They never even think in terms of getting a loan. They simply use the SBOS to execute all the day-to-day workflows that go into running their business, drawing (whenever necessary) on their always-on credit to smooth out cash flow disruptions and fund investments in their business’s growth.

Doesn’t that sound like a dream worth pursuing?

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Fundbox.

Fundbox is the pioneer of embedded capital solutions for SMBs, leading the charge in best-in-class finance offerings since 2015. Fundbox offers a comprehensive suite of products designed to support SMBs’ capital needs, including invoice financing, merchant cash advances, lines of credit, term loans, payroll protection, and more. By integrating with the digital tools businesses already use, Fundbox delivers fast and seamless access to capital, empowering the small business economy. Fundbox has partnered with leading SMB platforms to help over 125,000 small businesses unlock growth with fast, simple access to over $5B of capital.