You may have heard about the email that federal government workers received last weekend asking them to list out five things they accomplished during the prior week. This ask, driven by the Department of Government Efficiency (not a real government department!), was made to, “ensure that federal workers are not ripping off American taxpayers, that they are showing up to the office and that they are doing their jobs,” according to White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt.

More than one million federal employees have replied to the email, motivated, I’m guessing, by the fear of losing their jobs (which both President Trump and Elon Musk indicated were likely outcomes for those that didn’t respond).

So, in solidarity with government employees who work in financial services regulation and policy (and who, in my experience, tend to be talented, hardworking, and service-oriented), I am using today’s newsletter to answer Elon’s question and share a little bit about what I did (and learned) over the last week.

#1: Built a solution to increase transparency for consumers into bank–fintech arrangements.

I was in Washington, D.C. this week to attend a TechSprint hosted by the Alliance for Innovative Regulation (AIR). The purpose of the TechSprint was to develop technology solutions and/or innovative policy frameworks designed to foster successful bank–fintech arrangements while mitigating consumer risk.

My team (shoutout Blue Oceans 5!) was one of seven teams that participated in the TechSprint, and I want to tell you a bit about the solution we developed — Deposit Finder.

The idea was to solve for the most fundamental need in bank–fintech arrangements, which the Synapse disaster clearly illustrated — for consumers to know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, 1.) where their money is, and 2.) if their money is safe.

The challenge in answering these questions in the age of fintech is twofold:

- If the consumer keeps their money outside the bank regulatory perimeter (e.g., stablecoins held by a crypto brokerage, a stored balance account held by a Money Services Business, etc.), it may be unclear to them that their funds may not qualify for FDIC insurance.

- If the consumer is keeping their money in a fintech app that works with a bank behind the scenes using a custodial account structure, their account may qualify for pass-through deposit insurance from the FDIC in the event of the bank’s failure, but only if specific titling and recordkeeping requirements are met. Today, there is no way for a consumer to verify that these requirements are being met.

Hence, Deposit Finder!

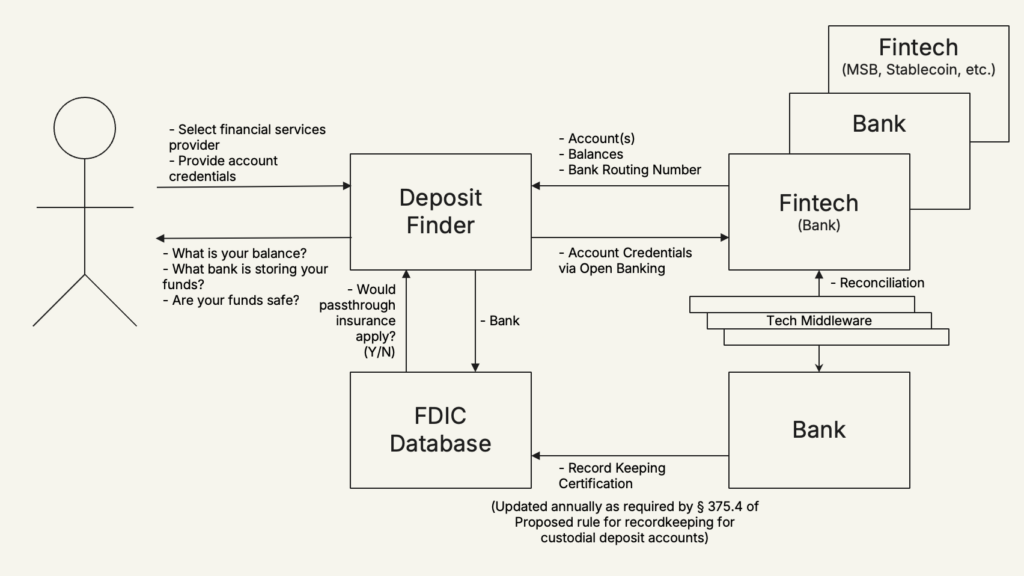

Here’s how it works:

- A consumer visits the FDIC’s website, accesses Deposit Finder, and types in the name of the financial services provider they work with.

- The consumer is then prompted to connect to the provider using their account credentials. Behind the scenes, Deposit Finder uses account aggregation (via Plaid, MX, Akoya, etc.) to securely verify the accounts that the consumer has with that provider, look up the account balances, and (if available) the associated bank routing numbers.

- For any accounts that do not have routing numbers, the consumer is informed that their account may not qualify for deposit insurance through the FDIC and given additional educational information to help them understand the implications.

- For any accounts with routing numbers, the FDIC leverages its own internal data to tell the consumer which bank(s) their funds are stored at. And, thanks to the FDIC’s new recordkeeping rule (which, for the purposes of our solution, we assumed will be finalized), the tool can also tell the consumer if pass-through deposit insurance would be likely to apply for any funds stored at banks through third-party fintech apps.

Here’s a rough sketch of the solution architecture:

In my opinion, Deposit Finder is a critical addition to the existing suite of consumer education tools that the FDIC already offers, which include BankFind (look up your bank to see if it is covered by FDIC insurance), EDIE (a calculator for estimating insurance coverage), and 1-877-ASK-FDIC (I called this number as an experiment and I had a lovely but ultimately unfulfilling chat with a gentleman named Alex).

The folks we pitched Deposit Finder to raised a lot of good questions and potential issues, including:

- Where would the FDIC get the money to pay for building and maintaining the tool? (Our answer: Higher assessment fees paid by banks that have third-party fintech programs.)

- What if the regulatory rules that the tool depends on (open banking and recordkeeping for custodial accounts) aren’t finalized, are rolled back, or are significantly altered? (Our answer: We believe they won’t be, though that’s far from a certainty … as I discuss below.)

- What if the FDIC is legally barred from telling consumers if pass-through insurance would likely apply to their fintech/bank accounts because that information is considered confidential? (Our answer: The ability to look up which banks your fintech accounts’ funds are stored at would still be valuable by itself, but we would also strongly encourage policymakers to not allow CSI restrictions to limit consumer transparency into bank–fintech arrangements. We need to figure out how to solve the Schrödinger’s cat problem with pass-through deposit insurance.)

#2: Saw a lot of innovation in standardization and data sharing.

I had to leave D.C. before the TechSprint was finished, so I didn’t get to see all of the solutions developed by the other six teams, but from what I did see, there seemed to be a common theme — standardization and data sharing.

This wasn’t a huge surprise to me. The TechSprint included problem statements specifically focused on data sharing and creating more transparency into bank–fintech arrangements for regulators. However, the solutions in this area that I did see were impressive. Lots of work went into building common data schemas, standardized reports and dashboards, and finding ways to apply AI (particularly to unstructured data).

This makes me very happy. In the last AIR TechSprint that I participated in (which was focused on the same problem space), my team proposed a Fintech Call Report, which is conceptually very similar to a lot of the work that I saw this week.

Also, for what it’s worth, there seemed to be a growing amount of support, from regulators and from industry, to have much of this work done by industry-led standard-setting organizations like CFES. This is a notable shift in sentiment.

#3: Discovered there is a surprising amount of industry pushback on the Henrichs Rule.

I had assumed that the FDIC’s proposed rule on recordkeeping for custodial accounts (which many are calling the “Synapse Rule”, but I think we should be calling the “Henrichs Rule” because we shouldn’t name good ideas after bad people or companies) would end up being finalized, with few changes. I felt confident in this, even after Donald Trump was elected and Travis Hill was appointed Acting Chairman of the FDIC.

From my view, the rule simply codifies what should have already been the best practices for banks working with third-party fintech programs to offer custodial accounts with transactional features. I figured there might be some quibbling over the details of the rule (there always is) but that the rule would move forward.

From what I heard this week, that may not be true.

The FDIC has received significant pushback from industry on the rule. More, quite frankly, than I was expecting. You can read the comments here, but the gist is that many feel the rule is too broad and inappropriately places the compliance burden on banks rather than on the end fintech programs.

Here’s how the comment letter from the Bank Policy Institute, American Bankers Association, and Association of Global Custodians put it:

While we agree with the FDIC that the inability to access deposited funds due to recordkeeping failures by nonbank entities is a problem that must be addressed, we disagree with the approach taken in the proposal, which is overly broad in scope and which inappropriately seeks to make banks responsible for business deficiencies observed at nonbank entities.

It sounds like the FDIC is taking this industry feedback seriously, which may result in significant changes to the rule (which, TBH, I would be fine with) or the rule being scrapped altogether (which I would strongly object to).

#4: Heard some updates on the BPI lawsuit against the CFPB over open banking.

The other regulatory rule that is drawing significant scrutiny right now is the CFPB’s final rule on open banking (AKA the Personal Financial Data Rights Rule).

As you likely know, the Bank Policy Institute (BPI) filed a lawsuit against the CFPB over the rule shortly after the rule was finalized back in October. As I wrote about recently, the Financial Technology Association (FTA) filed a motion to intervene in the case, motivated by a very reasonable fear that the CFPB would not choose to defend its own rule.

Well, this week, the BPI and the CFPB jointly filed a motion asking the court for a 30-day stay in the proceedings and the rule’s compliance deadlines, which the court granted (while also denying the FTA’s motion to intervene).

So, now the question is, “What will the CFPB do during the 30-day window?”

My best guess is that they will quietly work with the banks to figure out how they can change the rule to accommodate some of the things that are important to banks to the Trump administration.

Here are some of the things that might change:

- Expanded secondary data use. Everybody except Rohit Chopra is cool with this. I expect it to happen. The question will be how far it goes.

- More banks exempted from the rule. The current rule exempts banks under $850 million in assets. I hear that some in the administration want this threshold to be significantly higher (maybe all the way up to $10 billion?) although I’m not sure why they would want that. It would be a bad outcome for community banks, as it would drive consumers towards the bigger banks that are willing and able to facilitate the data-sharing experiences they expect. Ironically, it would also potentially be good for the existing data aggregators (Plaid, MX, Finicity) because they already have coverage (via screen scraping) of smaller banks, which would be hard for new aggregators to replicate quickly.

- Liability and third-party risk management. Banks want hard and fast rules that limit their liability, and they want someone else (e.g., regulators, FDX, etc.) to do third-party risk management and certification. I have no idea if they will get what they want or not.

- Payment initiation. JPMorgan Chase wants payment initiation to be descoped from the rule because broad adoption of pay-by-bank would be bad for their debit card and credit card franchises (even though JPMC also offers pay-by-bank today). Data aggregators and large, payments-oriented fintech companies like Stripe want payment initiation to stay in the rule. This one may very well come down to a question of who has more pull with President Trump and Elon Musk — Jamie Dimon or the Collison brothers?

- Allowing banks to charge for the data. The big banks really want this, and I think it will happen. The question is, under what circumstances will it be allowed? Will banks be able to charge a set amount to cover their costs or a variable amount depending on market demand? Will they be able to charge for non-covered data (e.g., loans, wealth, etc.) but not covered data (e.g., deposits, cards, wallets)? Will they be able to charge for premium use cases (e.g., cash flow underwriting) but not basic use cases (e.g., account verification)? No one seems to know.

Of course, if we assume that the CFPB decides to revamp the rule, it will need to go back through the standard regulatory process, as required by the Administrative Procedure Act. This will ensure that we will all have plenty more opportunities to weigh in on these questions!

#5: Read a lot about the drama that has engulfed the CFPB.

If you haven’t taken the time to read all of the back-and-forth between the National Treasury Employees Union (representing the employees at the CFPB) and Russell Vought (acting on behalf of President Trump and, I presume, Elon Musk), you should. It’s quite dramatic.

As you probably know, the union sued Vought over his attempts to functionally shut down the CFPB and fire most of its employees. This resulted in a federal judge temporarily blocking the Trump administration from firing CFPB employees without cause, conducting a reduction-in-force, deleting or removing CFPB data, or transferring or returning any of the agency’s funds.

Since then, Vought and the union have been taking turns responding to each other’s claims, and the specific details being shared by CFPB employees (under penalty of perjury) are pretty alarming.

Here’s just one example from Matthew Pfaff, Chief of staff for the Office of Consumer Response (which is responsible for collecting, monitoring, and responding to consumer complaints):

On February 13, 2025, members of the “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) requested that Consumer Response define competitive areas—areas explicitly required by statute—for purposes of a Reduction in Force (RIF). I drafted a memo that provided information about the teams within Consumer Response that align to specific statutory obligations.

None of the teams listed in the memo, which align to statutory obligations, have been activated to work. As a result, the complaint handling operation has experienced a significant disruption.

I expect that more than 10,000 complaints are currently awaiting federal staff review. This is a large and unprecedented backlog.

Not good.

More to come on this story, I am quite sure.