The biggest threat to consumers’ financial health isn’t overdraft fees or credit card late fees or banks paying below-market rates on savings accounts.

It’s gambling.

The resurgence of gambling in our culture has already had devastating consequences on the lives and balance sheets of American consumers and their families.

There are plenty of statistics that demonstrate the truth of that statement, but I’ll settle for three.

- The legalization of sports betting, which was unlocked by a 2018 Supreme Court decision, reduced net investments (in products like savings accounts or mutual funds) by bettors by nearly 14%, and every dollar spent on sports betting reduces net investment by $2.13. This effect is more significant in financially constrained households.

- There have been cumulatively 23% more Google searches nationally than expected for topics related to gambling addiction, such as “gambling addiction hotline” or “am I a gambling addict,” than expected since the Supreme Court ruling. Those search rates are, as you might guess, significantly higher in states that have legalized sports betting.

- When sports gambling is legalized, the effect of NFL home team upset losses on intimate partner violence increases by around 10 percentage points, and those effects are more pronounced in states where mobile betting is legalized.

These stats are obviously concerning on a societal level, but they also matter, more specifically, to those of us working in financial services, for two reasons:

- When gambling subverts individual and household balance sheets, it negatively impacts the business opportunities available to banks and fintech companies. When a consumer spends more money on same game parlays, they have less money available to save, invest, or use to pay their bills.

- The line between financial products and gambling products is being increasingly blurred, and, as a result, the temptation for banks and B2C fintech companies to get into the gambling business is growing.

The first point is (I hope) fairly obvious and doesn’t require any additional explanation.

The second point is worth elaborating on.

Robinhood, Coinbase, and the Financialization of Literally Everything

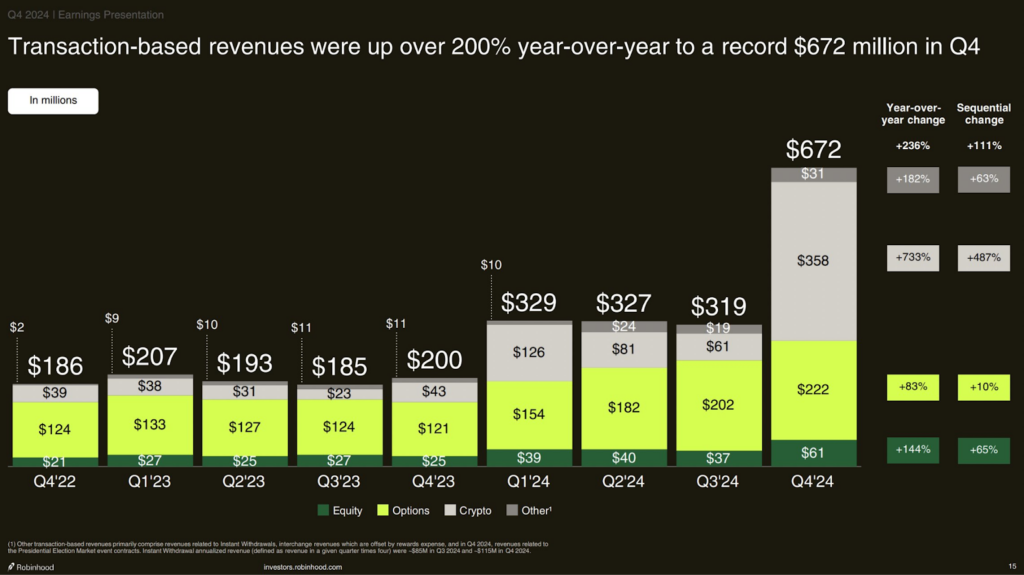

The last quarter of 2024, which happened to coincide with the election of President Trump, was a really good quarter for Robinhood:

What changed in Q4 2024?

Crypto!

For the last couple of quarters, crypto prices and trading volumes have been surging wildly, and this activity level (along with the promise of a looser regulatory environment) has motivated certain financial services executives to be far more candid about their visions for the future.

First up, we have Robinhood, which, in its own words, was built to be “a new kind of financial services company—one aimed at helping everyone build toward their financial goals.”

In pursuit of this vision, the company partnered with prediction market Kalshi to offer the ability for its customers to bet on the outcome of the U.S. Presidential Election (a bet that attracted roughly half a billion dollars in one week). More recently, Robinhood attempted to extend this same capability to allow customers to bet on the Super Bowl before pulling back at the request of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Despite the failure, Vlad Tenev, CEO of Robinhood, remains bullish, telling investors, “Prediction markets are the future.”

Then we have Coinbase, which, like Robinhood, claims a mission rooted in financial empowerment, and, like Robinhood, reported outrageously good Q4 2024 results (revenue of $2.27 billion against expectations of $1.87 billion).

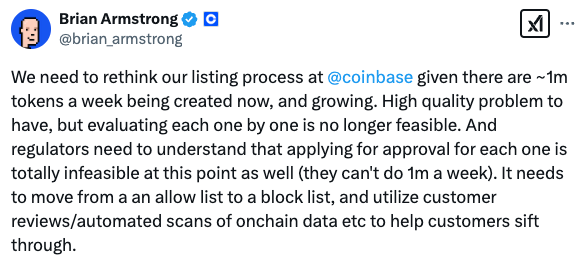

Like Tenev, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong has been pushing to open access to new asset classes for retail investors. Over the last couple of months, Armstrong has argued for a more permissive approach to listing memecoins:

Utilizing distributed ledger technology to tokenize securities (of public and private companies) and make them available fractionally, 24×7 to non-accredited investors:

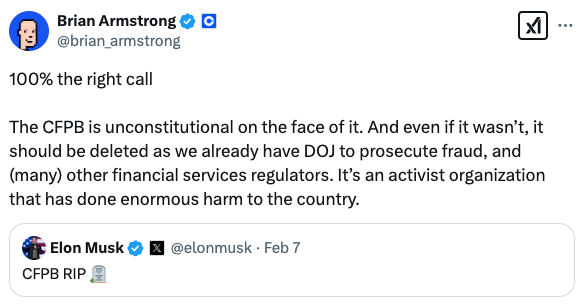

And deleting the CFPB:

Everything that Tenev and Armstrong are pushing for — expanded access to sports betting and prediction markets, tokenized securities, loose/nonexistent crypto regulation, gutting consumer protection regulation — seems feasible over the next four years, given the Trump Administration’s actions to date.

In fact, I would guess that many of these issues will be discussed inside the White House today at the Crypto Summit, which both Tenev and Armstrong are attending.

For Robinhood and Coinbase, it’s smart business.

Despite some efforts at diversification over the last couple of years, both companies still make a majority of their revenue transactionally, which means they are incentivized to keep their customers as active (buying/selling/trading) on their platforms as possible. And the best way to do that is to give customers a wide range of fun things to bet on.

Thus, the utility of memecoins and sports betting to Coinbase and Robinhood isn’t the expected value of the bets placed on those assets by their customers (which is overwhelmingly negative). It’s the ability of those assets to keep their customers engaged with their platforms.

This business model — what I’ve previously called Speculation-as-a-Service — isn’t common today in mainstream consumer financial services. For the most part, banks and B2C fintech companies make money through the combination of deposit storage and lending (net interest margin) and transaction fees for facilitating payments (debit and credit card interchange).

However, what concerns me is that the success of Robinhood and Coinbase and the permission structure that will be created by the Trump Administration’s regulatory priorities will tempt banks and B2C fintech companies to experiment with Speculation-as-a-Service as a business model.

My concern here is not hypothetical. It started happening the last time that Robinhood and Coinbase were booming.

Companies like DriveWealth and NYDIG spun up the infrastructure to enable banks and B2C fintech companies to offer fractional stock investing and cryptocurrency investing to their end customers, and we started seeing announcements like this:

And this:

Before this trend could deeply take root, the Fed raised interest rates, the bottom fell out of the crypto market, and regulators started cautioning banks to be careful with anything novel.

However, it’s easy to imagine an alternate universe where those things didn’t happen in 2022 and banks and fintech companies’ embrace of Speculation-as-a-Service continued chugging along full steam.

What would the market look like today in that alternate universe? Would community banks have leveraged FIS and NYDIG to offer memecoin investing to their customers? Would Cash App have added integrated sports betting?

Maybe. Or maybe not.

But if the recent regulatory and legislative success of the gambling industry and the Trump Administration’s actions over the last two months are any indication, I fear we will find out for ourselves over the next four years.

So, with that grim prognostication in mind, allow me to end this essay by offering two pieces of advice for banks, B2C fintech companies, and financial services policymakers.

Two Pieces of Advice

1.) Start measuring customers’ financial health.

The most sustainably successful businesses are those that align their long-term interests with the long-term interests of their customers.

In financial services, we know what outcomes consumers aim for in the long run — financial stability, economic freedom, and (ultimately) the opportunity to build wealth for themselves and their loved ones.

What’s strange in financial services is that we don’t have any common metrics that we can use to measure consumers’ progress towards those outcomes.

This matters because it makes it difficult for incumbent banks and B2C fintech companies to objectively evaluate the potential of new fintech innovations and decide if (and how) they should offer them to their customers.

Crypto is a great example.

If you are setting your product roadmap based solely on what your fastest-growing competitors are doing, you might conclude that you need to go all in on (depending on the year) NFTs or memecoins. If you are setting your roadmap based entirely on what your regulators or bank partners are fully comfortable with at that moment, you would likely conclude that you need to stay as far away from crypto as possible.

However, if you are objectively looking at crypto, solely through the lens of what is best for the long-term financial health of your customers, and if you can run small-scale experiments with different crypto products and measure the impact of those experiments on your customers’ financial health, you might come to a more nuanced conclusion, something like, “we should only offer bitcoin investing and we should strongly encourage our customers to adopt a long-term investment strategy like dollar-cost averaging.”

To develop an objective view of consumers’ financial health, the industry needs to develop a set of common metrics that we can use to measure consumers’ financial health and the impact of different products on it. This is a point that the former Acting Comptroller of the Currency, Michael Hsu, repeatedly made during his tenure leading the OCC:

Much of the banking system continues to be organized by product and service lines or by geographies. The profitability and risk of those things are measurable, and we know that historically, what gets measured gets done. I believe we can do better and truly put consumers front and center by measuring their financial health and supporting their efforts to improve it. Imagine if there were clear and objective measures of consumers’ financial health.

Hsu used the term “vital signs” to describe these measures, and he proposed (based on research done by the OCC) that they focus on three specific areas:

- Positive Cash Flow — Allows consumers to meet their week-to-week financial obligations while also (ideally) setting some money aside for savings and investment.

- Liquidity Buffer — The balance of liquid accounts and credit available is sufficient for consumers to withstand unexpected expenses and/or drops in income.

- On-Time Payments — Being current on debts indicates that consumers can regularly meet their debt obligations and avoid delinquency and over-indebtedness.

Credit scores do a decent job of measuring a consumer’s ability to regularly make on-time payments, but we don’t have industry-standard metrics for measuring positive cash flow and liquidity buffers.

The good news is that the data necessary to measure those areas has become much more available, thanks to the rise of consumer-permissioned data sharing. However, there is still a lot of work to be done to build standardized financial health scores and monitoring services on top of that data.

Banks, B2C fintech companies, and regulators should continue to engage in that work over the next four years.

2.) Make saving money more fun.

It’s very important for those of us who care deeply about the field of financial health to acknowledge a simple truth — financially unhealthy behavior is popular because it’s fun.

You can scoff at that if you want, but the fact of the matter is that gambling and impulse shopping are really fun, and financial products that enable those activities will naturally be easier to sell than financial products that don’t.

If we can accept that fact, then it poses a critical follow-up question: Can financial products that enable financially healthy behaviors like saving be more fun?

I think they can.

They’ll never be as fun as gambling and impulse shopping. Instant gratification and sensation seeking (the tendency to pursue intense, risky experiences) are powerful motivators of human behavior, and they’re not naturally compatible with financially healthy decision-making.

However, I do think there is an opportunity (through better and more intentional product design) to close a substantial portion of the “fun gap” between financially healthy products and experiences and financially unhealthy ones.

And again, this isn’t me theorizing. There are proven examples of fun, financially healthy products in the market today.

The first one I want to mention is Digit.

Long-time readers will know that I was a big fan of Digit, the fintech app that would automatically squirrel away small amounts of money from your checking account into a separate savings account based on a continual analysis of your cash flow patterns.

One of the things I loved about it (in its early days, before it was acquired by Oportun) was the text-based user interface, which would inundate you with encouraging updates about your progress and affirming GIFs about how awesome you are:

It might seem like a small thing, but this stuff matters. It’s the same reason why Robinhood used to celebrate customers’ trades with virtual confetti.

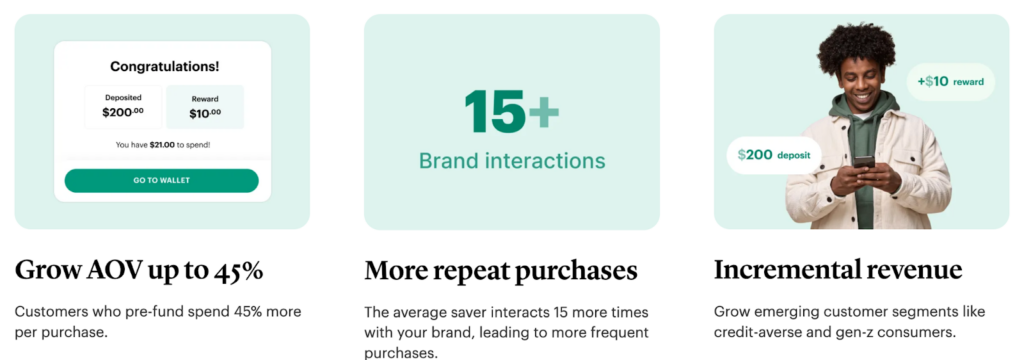

The second example I want to discuss is Save Now, Buy Later (SNBL).

SNBL is the bizzaro version of BNPL. It provides the same embedded payment capability within key points in the shopping journey in e-commerce websites and apps. The difference is that while BNPL is designed to facilitate instant gratification (through credit), SNBL is built to encourage delayed gratification (through savings).

A customer finds something they want to buy online. The merchant presents them with the option to save money in order to make that purchase at a later date. The consumer selects from a number of different options for how to save up the money (set and forget, one-time deposit, payment roundups, crowdfunding, etc.) and starts saving. The merchant may chip in rewards to help accelerate the customer’s progress (rewards can only be redeemed as purchases). Once the customer reaches their goal, they are notified and directed to the merchant to complete the purchase.

It’s essentially Amazon Wish Lists with embedded savings accounts.

And according to Accrue (an early pioneer of SNBL in the U.S.), it works. It encourages shopping (fun!) without requiring impulse spending (responsible!)

The last example I want to throw out is prize-linked savings accounts (PLSAs).

PLSAs are savings accounts that pay little to no interest to individual depositors but instead pool that interest into larger prizes that depositors can win in periodic lotteries. They are designed to encourage saving by giving customers who deposit more money better lottery odds (e.g., every $50 saved = another lottery ticket). This approach is irrationally appealing to people in the same way that gambling is (humans often prefer the chance of winning big to the certainty of winning small), but it removes any possibility of the consumer losing money (you’re not risking your deposit … just some or all of the interest you could have earned on it).

There hasn’t been a ton of research done on PLSAs, but the research that we do have suggests that they work extremely well.

Additionally, the anecdotal evidence from bank and non-bank providers that have offered PLSAs (which still aren’t very common in the U.S.) supports that same conclusion.

Walmart, in partnership with Green Dot and Commonwealth, launched a national prize-linked savings program through its prepaid card in 2017, which resulted in customers increasing their savings by 35% on average and, collectively, more than $2 billion saved by Walmart customers in just two years.

Truist ran a pilot with Commonwealth in 2021 to offer prize-linked savings to its customers. In just six months, the bank saw more than 25,000 households sign up, resulting in $37 million in new savings. The following year, Truist acquired Long Game, a fintech company specializing in prize-linked savings and other gamified financial health strategies.

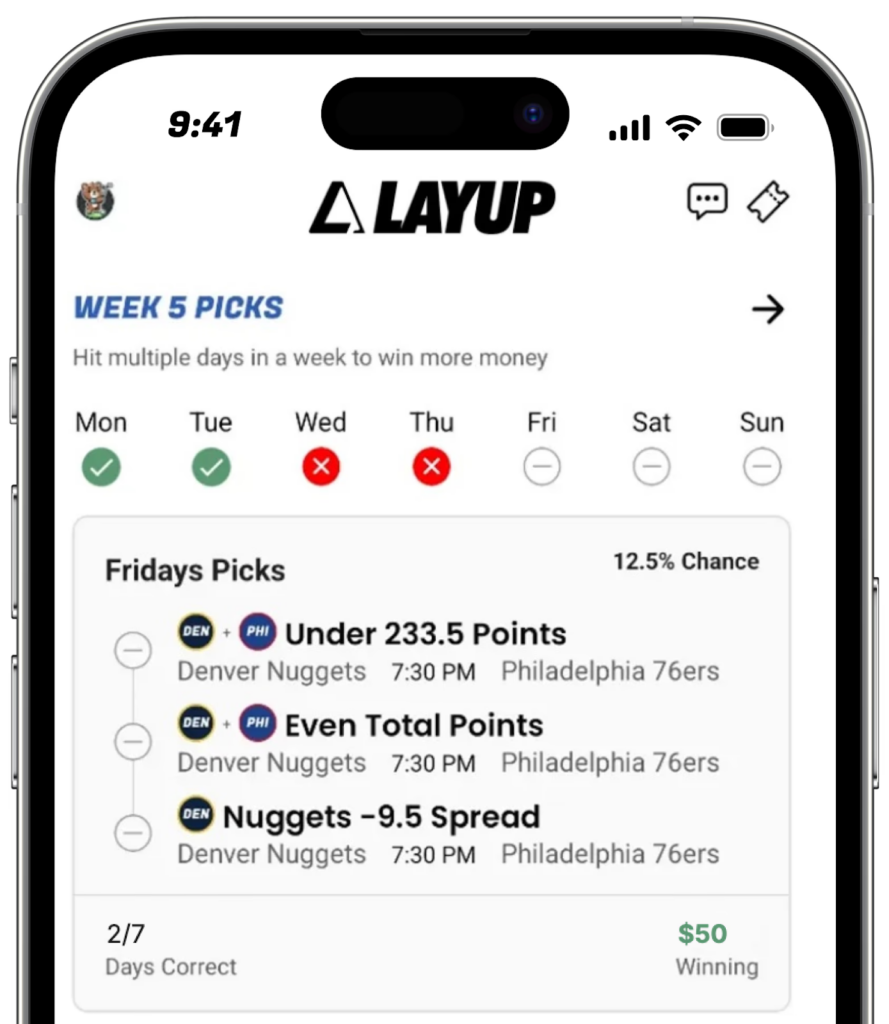

Perhaps my favorite recent example (which I have written about before) is Layup, a prize-linked savings app that uses sports betting (via the randomized assignment of picks on daily games with 50/50 betting lines) to determine the outcomes of its lotteries, in an attempt to entice sports bettors into a more financially healthy alternative.

All of these examples — more fun UIs for savings products, SNBL, and PLSAs — deserve significantly more experimentation and investment from banks and B2C fintech companies (and their VCs) than they have been getting. And regulators and policymakers should do everything possible to encourage this experimentation and investment.

(Editor’s Note — PLSAs are a good example of where regulators and consumer advocates can make a difference. We passed a federal law to encourage banks and credit unions to offer PLSAs in 2014, but despite that, banks and fintech companies interested in prize-linked savings are still hamstrung by inconsistent state laws, which, in some cases, require PLSAs to offer interest comparable to non-PLSA savings accounts [which defeats the purpose of PSLAs] or restrict which types of financial institutions can offer PSLAs. We need to harmonize state laws governing PLSAs!)

The Pendulum Will Swing Back

Eventually, there will be a large-scale societal backlash against gambling in this country.

I don’t know exactly when it will happen. Or what it will look like.

But it will happen.

Consumers can only get hurt like this for so long before something breaks.

And when the pendulum swings back, the banks and B2C fintech companies that facilitated that consumer harm will get crushed by it. Robinhood and Coinbase may not care about that, but everyone else should.

Long term, financial health is a better business to be in than gambling.