An easy way to spot emerging trends is to look for examples of market incumbents overreacting.

It’s not a common occurrence. Indeed, much of the modern theory of disruption is premised on the idea that market incumbents tend to underreact rather than overreact when confronted by some new (and potentially disruptive) technology or customer behavior.

So, when it does happen — usually in an area where a small number of incumbents have enjoyed an unusually long period of dominance — it’s worth sitting up and taking notice.

My favorite recent example is Pay by Bank.

JPMorgan Chase submitted a comment letter to the CFPB as a part of the bureau’s rulemaking on Open Banking. The comment letter was adamantly opposed to the inclusion of payment initiation (i.e., the sharing of a consumer’s routing and account numbers) within the scope of the Personal Financial Data Rights Rule:

The payments ecosystem is complex with significant nuances across networks, types of transactions and constituents. The CFPB’s proposal ventures into regulating the payments ecosystem without proper consideration of the costs, interactions among participants, and significant risks this proposal would create. Requiring the sharing of payment initiation information will be a catalyst for significant growth of “Pay by Bank” models, a payment method that is ill suited, yet is increasingly being adopted, for many types of transactions

If you don’t read many regulatory comment letters, you’ll just have to trust me — that is a scathing criticism in bank lawyer speak.

So, why is JPMorgan Chase (along with a number of other large incumbents in the payments space) so freaked out by Pay by Bank?

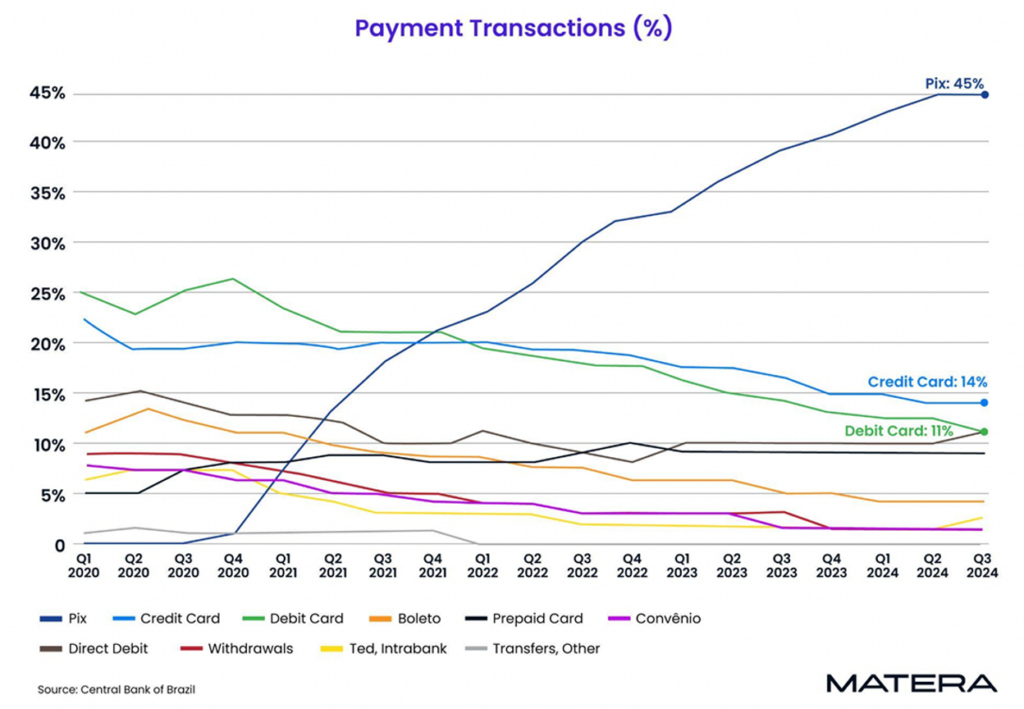

I think this chart, which shows the percentage of payments by payment type in Brazil between Q1 of 2020 and Q3 of 2024, is probably our best answer:

Pix, the instant bank-to-bank payments system created by the Central Bank of Brazil, has seen enormous, unprecedented growth over the last four years. In Q3 of last year, the number of Pix transactions was 80% more than credit and debit card transactions combined.

Now, to be clear, Pix is a unique animal. Its success is the result of a combination of regulatory, technological, and cultural factors that aren’t easily replicable. However, it’s still an important proof of concept. If you think bank-to-bank payments can’t overtake card-based payments in a specific market, all you have to do is look at Pix in Brazil, and you’ll see that’s not true.

That proof of concept is why JPMorgan Chase is simultaneously trying to stop Pay by Bank from becoming ubiquitous in the U.S. through the CFPB’s Open Banking rule *and* preparing for a future in which Pay by Bank is far more commonplace by partnering with Mastercard to launch a Pay by Bank service for billers.

It’s also why I feel confident that Pay by Bank will be one of the most important trends in fintech over the next five years.

So, in today’s essay, I want to delve into Pay by Bank: what it is, why it’s already an important competitor to both credit cards and debit cards, and why its long-term potential goes far beyond simply facilitating cheaper payments.

What Is Pay by Bank?

Let’s start with a definition.

In the simplest and broadest possible terms, Pay by Bank is any payment method that enables the transfer of funds directly between bank accounts.

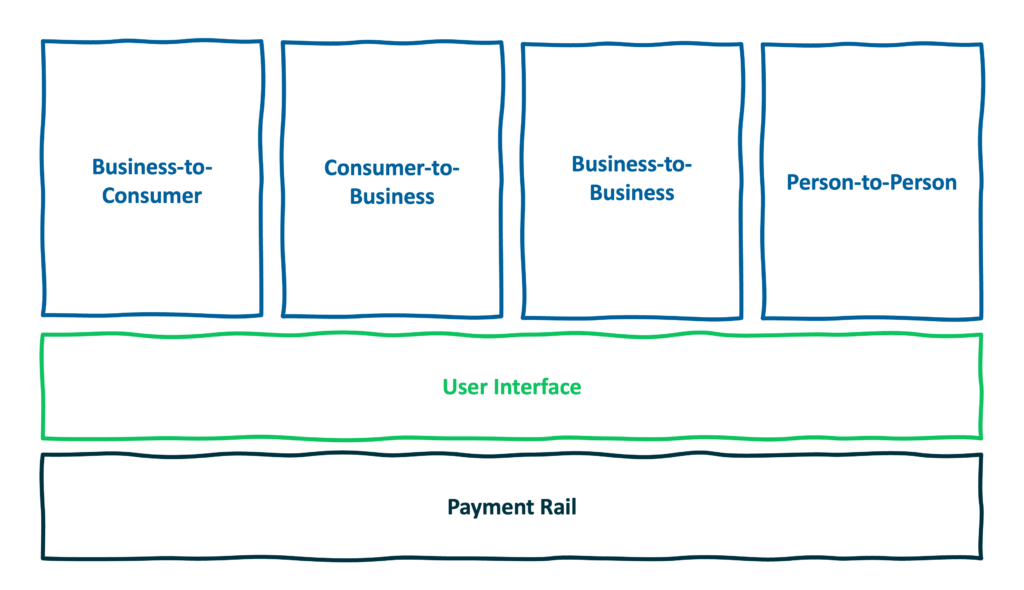

As with any other payment method, Pay by Bank has four categorical uses: business-to-consumer (e.g., payroll, benefits dispersal, etc.), consumer-to-business (e.g., retail and e-commerce, bill pay, etc.), business-to-business (e.g., accounts payable, accounts receivable, etc.), and person-to-person payments.

Given the breadth of this definition, a lot of different payment solutions can be considered to be a form of Pay by Bank. Those solutions can be divided into two distinct layers: the payment rail (e.g., check clearing, ACH, FedNow, etc.) and the user interface (e.g., paper checks, online portals, merchant apps and mobile wallets, etc.)

The inherent characteristics of different payment rails (authorization processes, settlement speeds, dispute rules, transaction limits, processing costs, etc.) tend to be the determining factor for which use cases those rails are applied to. However, what we have seen in recent years is that the user interface that is layered on top of the payment rail can have a big impact on the success of different use cases as well.

This is where Open Banking comes in.

Open Banking is a critical ingredient for modern Pay by Bank experiences because it streamlines the payment initiation process. Instead of requiring a customer to know (or look up) their routing and account numbers, you can, instead, simply ask them to log in to their digital banking portal and the routing and account numbers are automatically retrieved and populated.

Thus, we can define modern Pay by Bank more narrowly by anchoring on a combination of electronic payment rails (ACH, RTP, FedNow, etc.) and digital user interfaces enabled and enriched by Open Banking.

This is usually the form of Pay by Bank that fintech companies and merchants are referring to when they talk about the potential of Pay by Bank to disrupt existing payment methods like credit cards and debit cards.

And that potential is slowly beginning to be realized.

Let’s start by exploring Pay by Bank’s ability to disrupt the credit card market.

Pay by Bank vs. Credit Cards

A common talking point in the Pay by Bank debate is payment processing costs.

Credit cards are expensive to accept (typically 2-3% of the transaction), and the conventional wisdom is that merchants despise paying those fees.

The reality, as usual, is a bit more nuanced.

Credit cards are popular because they are easy and familiar for consumers to use (both online and in-store), accepted (almost) everywhere, safe to use in risky or novel situations, and rewarding.

These attributes make them the obvious choice for *some* payments use cases.

Some, but not all.

The trick to understanding where Pay by Bank can add value is to distinguish between use cases where credit cards are the best answer and use cases where credit cards are simply the default answer.

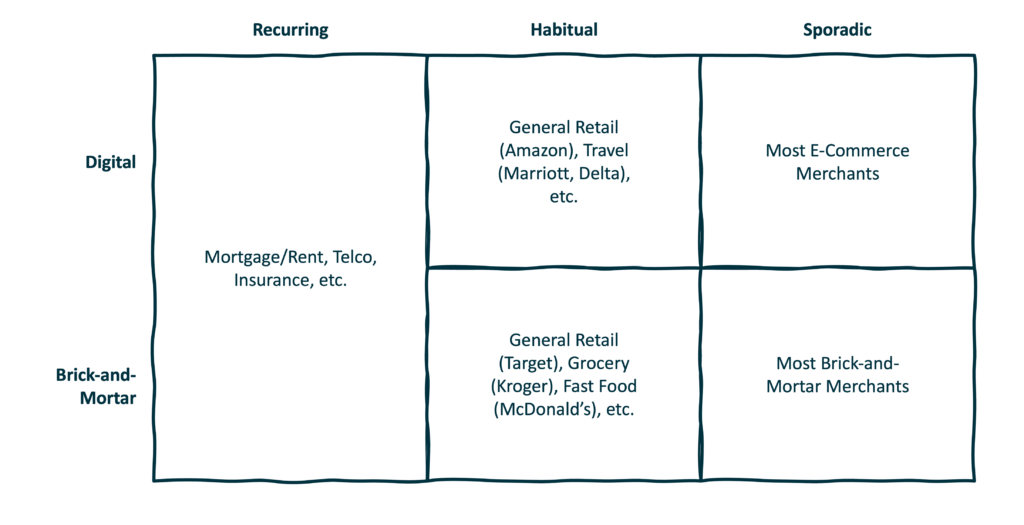

Let’s look at consumer-to-business use cases as an example.

A useful way to divide up these use cases is by channel and by frequency of interaction.

Recurring bills and subscriptions is an area where we already see significant adoption of Pay by Bank.

Most billers offer online portals for customers to set up auto-pay because it’s convenient for customers to set it and forget it, and it creates stickier, lower risk relationships for the biller.

The billers that process large transactions (mortgage, insurance, etc.) will often require their customers to pay via a bank account rather than with a credit card, as the 2-3% fee at those transaction sizes is a material cost. These companies generally have sufficient leverage with their customers to dictate what payment method(s) they will use (i.e., you don’t pick your mortgage servicer … they pick you, and then they tell you how to pay).

(Editor’s Note — Bilt’s pay-your-rent-with-a-credit-card offering is the exception that proves the rule. It takes an extraordinary amount of leverage to convince large billers like property management companies to accept credit cards.)

For recurring transactions that are smaller, less essential, or provided by companies that operate in more intensely competitive industries, the dynamic is slightly different. The mutual desire for auto-pay is still there. However, the biller has less leverage with the customer, so they generally need to offer some type of incentive to get them to choose Pay by Bank over a credit card.

The telco industry is a good example.

I am a happy, long-time Verizon customer. For years, Verizon has offered a discount of $10 per line when you sign up for paperless billing and agree to pay with a debit card or bank transfer. This offer is incredibly compelling (the savings I get across the multiple lines on my plan more than compensate me for the credit card points I am forgoing), and it’s a smart investment for Verizon because it saves them money (on both paper bills and credit card interchange fees) and gives them a significant marketing advantage in a highly competitive industry (i.e., they can advertise their plans at a lower price because the $10/line discount is conditionally available to all customers). It’s this combined cost savings and marketing benefit that justifies the size of the discount, which wouldn’t be justifiable based on cost savings alone.

On the other end of the continuum, you have what I call “sporadic” e-commerce and brick-and-mortar merchants. These are the one-off or infrequent purchases that we make in our day-to-day lives, where there’s no loyalty or established habits driving our choices.

This is where credit cards dominate. Consumers value certainty when interacting with merchants they don’t know (e.g., you know they likely accept credit cards, you know your transaction will be safe, etc.), and they value the ability to aggregate rewards across a disparate base of infrequently patronized merchants.

The merchants on this end of the continuum may not like paying credit card interchange fees, but they do benefit from the ubiquity, certainty, and loyalty that those fees help pay for.

The merchants in the middle of the continuum are the ones that are the most interesting to me.

These are what I refer to as “habitual” or “everyday spend” merchants, meaning those that sell goods or services that consumers purchase consistently and, thus, where there are opportunities to cultivate brand-specific trust and loyalty. This includes merchants that process payments online (Amazon, Marriott, Delta, etc.), in-store (Target, McDonald’s, Starbucks, etc.), or (increasingly) both.

Habitual merchants don’t have the same leverage or predictability that billers have. However, they do have a great deal more trust and loyalty with their customers than sporadic merchants have.

As such, they usually accept credit cards, but many are eager to experiment with alternatives that can enhance customer loyalty while reducing their payment processing costs.

One such alternative, which is very well established within this category of merchants, is co-brand credit cards.

The appeal of co-brand credit cards for habitual merchants is straightforward. Instead of paying interchange fees that fund loyalty programs for credit card issuers, the merchant issues its own credit card and uses the savings on the fees for on-us transactions to fund its own loyalty program, which typically combines monetary rewards (e.g., miles, points, cash back, etc.) and experiential rewards (e.g., free checked bags and priority boarding for an airline’s credit card customers).

Now, you may note the irony that many of the merchants that most hate credit card interchange fees are also the most likely to issue their own credit cards.

Historically, there is a very good reason for this.

Remember, the appeal of credit cards to consumers isn’t just rewards. It’s also their utility as a payment instrument (especially in-store). Credit cards are easy for consumers to use and for merchants to accept. The infrastructure and consumer behavior are already well-established, which means there is very little friction when a merchant like Walmart or Amazon adds their own proprietary card into the mix.

This is not to say that co-brand credit cards are the perfect solution for merchants. Far from it. Credit cards are complex and expensive to stand up. For every large habitual merchant or biller that has the scale and resources to justify investing in a co-brand credit card, there are literally tens of thousands of smaller ones (coffee shops, grocery stores, niche subscription services, etc.) that don’t, even though they have the brand trust and loyalty necessary to steer their customers to alternative payment methods.

(Editor’s Note — Besides the expense and operational complexity of credit cards, there’s also a brand risk for merchants. Do you really want some of your customers to get trapped in a revolving debt cycle because of your product? Is that brand risk worth the incremental revenue?)

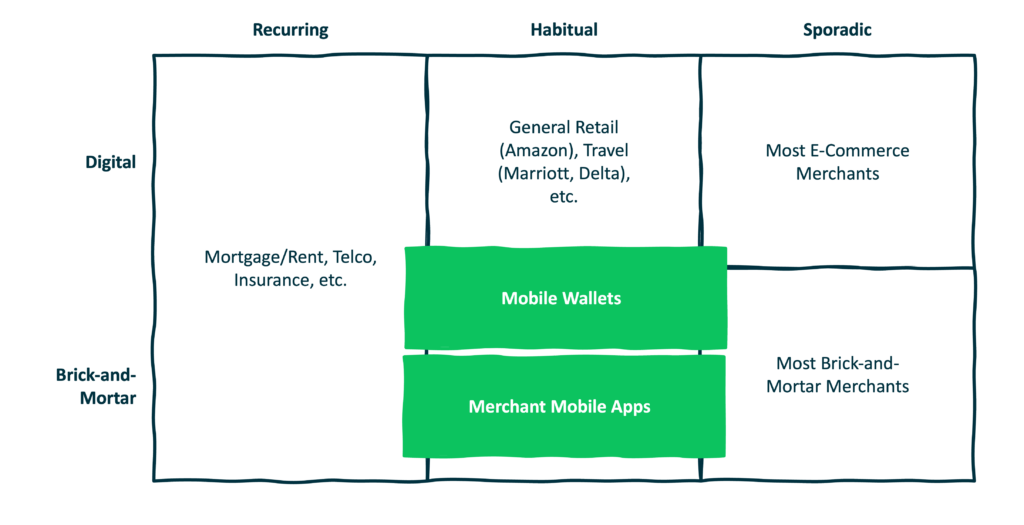

Luckily, in the world of consumer-to-business payments, we have started to decouple the user interface layer from the payment rail layer. This isn’t good news for co-brand credit card issuers, but it’s very good news for consumers, merchants, and Pay by Bank aficionados.

There are two different examples I want to touch on, both of which are most relevant to habitual brick-and-mortar merchants.

The first example is mobile wallets.

It’s taken a while, but merchant acceptance of mobile wallets like Apple Pay and Google Wallet (which leverage near-field communication and on-device biometric authentication for secure contactless payments in stores) is starting to become ubiquitous enough (75%-85% of retailers in the U.S., from the data I’ve seen) to be a viable alternative to payment cards.

Now, of course, that doesn’t mean that consumer adoption will get to that same level anytime soon (it won’t) or that increasing usage of mobile wallets will lead to a decrease in credit card usage (in fact, credit cards are one of the primary payment methods supported within Apple Pay and Google Wallet).

However, the mere act of decoupling the underlying payment rail from the payment UI opens the door to non-credit card alternatives.

This decoupling happened very early on for billers (Verizon has been offering discounts for far longer than Pay by Bank has been a term) and for e-commerce merchants (PayPal engaged in very aggressive payment steering for years). And now it’s coming to brick-and-mortar merchants, thanks to the growing adoption of mobile wallets (and regulatory pressure that has forced Apple to open up developer access to its NFC capabilities), and one of the first manifestations of it in the market is (unsurprisingly) Pix:

The second example is merchant mobile apps.

Mobile apps are not a new idea for habitual brick-and-mortar merchants. However, their strategic importance has grown over the last 15 years as merchants have realized the role they can play in steering their customers’ behavior.

Starbucks is the canonical case study for this. The company’s mobile app launched in 2009 with a rewards program, store locator, and nutrition information. However, in 2011, the company added mobile payments capabilities to the app, allowing users to pre-fund a stored balance (i.e., prepaid) account and to use that account to make payments in-store via a barcode. This innovation, enhanced with additional in-app conveniences like mobile pre-orders (2014) and curbside pickup (2020), proved enormously successful for Starbucks, enabling them to grow sales, reduce payment processing costs, and increase engagement with their loyalty program.

Another example is Target, which recently consolidated its loyalty program (Circle) and its suite of proprietary payment products (the Target RedCard co-brand credit card, decoupled debit card, and prepaid card) into a single mobile experience. The newly renamed Target Circle Cards (which account for roughly 18% of Target’s overall payment volume) can now be embedded directly within the “Wallet” tab of the Target mobile app, allowing customers to earn 5% cash back on Target purchases without actually having to pull out the plastic card.

The work that these early innovators have done to merge brand-specific mobile apps with embedded payments functionality (including Pay by Bank) has created a roadmap, which many other habitual brick-and-mortar merchants (large and small) are now following, enabled by new wallet-as-a-service providers and Pay by Bank providers like Trustly.

Pay by Bank vs. Debit Cards

At this point, I hope what you’re thinking is something like, “OK, I understand why merchants would want to steer consumers away from credit cards and why Pay by Bank, enabled by Open Banking and mobile apps and wallets, is a potentially good solution for that. But what about debit cards? If the goal is to reduce payment processing costs and reinvest some of those savings into brand-specific loyalty programs, wouldn’t debit cards work just as well or better than Pay by Bank?”

This is a GREAT question.

On the surface, you’re right. Regulated debit cards (meaning debit cards issued by banks with more than $10 billion in assets) make up a majority of the debit cards in the market (big banks own the lion’s share of deposit accounts in the U.S.), and interchange fees on these cards are capped at $0.21 plus 0.05%, thanks to the Durbin Amendment. That makes regulated debit roughly as inexpensive as a Pay by Bank transaction (depending on the payment rail and add-on services).

So, why not just steer consumers away from credit cards and towards debit cards? Or at least make it one of several different options (along with Pay by Bank and co-brand credit cards), as Verizon originally did when it introduced its $10/line discounts?

Well, to paraphrase a line from my friend Simon Taylor, the reason you want to focus on Pay by Bank, and specifically Pay by Bank powered by Open Banking, isn’t because it’s cheaper. It’s because it’s better.

Debit cards (and credit cards, for that matter) don’t tell merchants anything about the customer who is using them. All you know, as a merchant, is whether the transaction was approved or declined. That’s it.

Open Banking-powered Pay by Bank can tell you a lot more.

When a customer connects their bank account, they are, at minimum, sharing their routing number and account number with you. However, they also have the option of sharing months of historical bank transaction data with you as well. This data can give merchants a much richer level of insight into their customers’ financial lives, and that insight can power a multitude of compelling products and product features, including:

- Cash Flow Smoothing. Imagine if a gas station knew, at the moment of the transaction, that a customer’s payment would cause them to overdraw their checking account and incur an overdraft fee, and the gas station could offer that customer a fee-free microloan to cover the transaction while protecting their short-term cash flow by aligning repayment with their paycheck schedule. Imagine if a telco company knew that a scheduled auto-pay would fail and cause the customer’s account to be disconnected, and the telco could proactively offer to shift that payment date to better align with the customer’s paycheck schedule. With Open Banking, these types of intelligent, contextually-aware Pay by Bank experiences are feasible.

- Personalized Offers. A debit card swipe can’t tell a merchant if the customer used that same card at their biggest competitor last week. Open Banking-powered Pay by Bank can, which unlocks an entire world of personalized offers and incentives, delivered in real time at the point of sale. Imagine, as a merchant, being able to instantly identify when a customer switches from making a habitual purchase (like a daily coffee) with you to making it with your competitor across the street and being able to send them a timed offer for the next day to win back their business.

- VIP Onboarding. Lots of Pay by Bank experiences are slower and more friction-filled than they need to be because traditional Pay by Bank products (checks, wires, ACH, etc.) lack access to the customer-level risk insights that would allow them to tailor the speed and friction of the experiences to match each individual customer’s risk profile. With risk insights gleaned through Open Banking, merchants can create streamlined VIP onboarding experiences for their best and lowest-risk customers rather than forcing them to endure the traditional lowest-common-denominator approach to risk management.

- Risk Monitoring. By contrast, merchants also need to know when their customers’ financial situations or behaviors have worsened and to use that insight to adjust their risk management strategies (authorizations, payment holds, etc.) in real time. This insight is impossible to glean through debit cards, checks, or traditional ACH transactions. However, with Open Banking-powered Pay by Bank, it’s doable.

- Lifetime Customer Value. Most fundamentally, permissioned access to a customer’s bank transaction data can help merchants better calculate each customer’s potential lifetime value. This insight can help merchants better align the incentives, rewards, and offers that each customer is given, thus ensuring that the savings generated by Pay by Bank are reinvested in the most optimal way.

The Bigger Pay by Bank Opportunity

We’re constantly told that merchants hate paying interchange fees.

I think this is true, but I don’t think merchants’ dislike of the card networks is because of payment processing costs. I think it’s because of the opportunity costs.

For a merchant, every credit card and debit card transaction is a missed opportunity to gather data about their customers and to invest in giving those customers more personalized rewards and experiences that will strengthen their relationship with the merchant.

To put it bluntly, today, Visa and Mastercard (and their issuers) hoard the data and brand loyalty that should be accruing to merchants.

For decades, the largest and most sophisticated merchants have found ways (co-brand credit cards, decoupled debit and prepaid programs, mobile apps, etc.) to circumvent that problem and reap the full benefits of the relationships they have built with their most loyal customers.

With modern Pay by Bank infrastructure, powered by Open Banking, that opportunity is now available to all merchants. Over the next five years, I expect we will see many of them capitalize on it.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Trustly.

Trustly is the global leader in Pay by Bank solutions. With Open Banking at its core, Trustly gives consumers and merchants a smarter and safer way to pay.