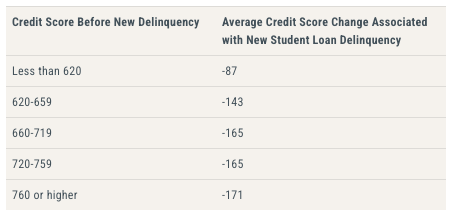

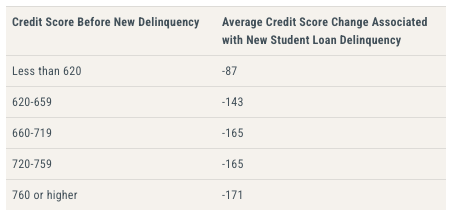

According to the New York Fed’s Liberty Street Economics blog, more than 9 million student loan borrowers will soon start to see substantial declines in their credit scores. Those declines will be larger for higher-score segments, with those in the 760 – 850 range seeing an average drop of 171 points:

That’s a big deal. And unless you’re a credit score nerd, you probably have no idea why this is happening or what it means.

Well, I am here to help!

Why Student Loan Borrowers’ Credit Scores Are Screwed Up

All of this started with the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March 2020, the Trump Administration suspended interest accrual and payments on federally held student loans (which represent about 85% of all student loans in the U.S). Borrowers could opt to continue payments, with amounts applied to the principal.

A week later, President Trump signed the CARES Act into law, which codified the payment pause through September 30, 2020, with 0% interest on Department of Education-held loans. Paused payments were reported as current to credit bureaus, protecting borrowers’ credit scores. The CARES Act also provided stimulus up to $1,200 per adult (plus $500 per child under 17) for individuals earning under $75,000 (phasing out at $99,000). Payments began in April 2020, reaching over 160 million people by mid-2020.

Over the next three years, the federal government continued to provide both fiscal stimulus to low-to-moderate income consumers and payment relief to student loan borrowers, even though the original justification for these interventions (economic uncertainty due to a global pandemic) was weakening as life got back to something resembling normal.

Here are the highlights from that period:

- August 2020: President Trump extended the student loan repayment pause and 0% interest through December 31, 2020.

- January 2021: President Biden extended the student loan repayment pause, maintaining prior relief terms. A second round of stimulus checks (up to $600 per adult plus $600 per child) were distributed to those earning under $75,000 (phasing out at $87,000), with over 147 million payments going out.

- March 2021: The Department of Education extended relief to over 1 million borrowers with defaulted Federal Family Education Loans (a type of government-subsidized private student loan), pausing interest and collections, and requesting credit bureaus to erase default records since March 13, 2020. The American Rescue Plan Act was also passed, authorizing additional stimulus of $1,400 per adult (plus $1,400 per dependent) for those earning under $75,000 (phasing out at $80,000). Payments totaled over 165 million by the end of 2021.

- April 2022: The Biden Administration announced another student loan repayment pause extension and introduced the “Fresh Start” program for 7.5 million defaulted borrowers, reporting their loans as current until one year post-pause.

- August 2022: The student loan repayment pause was extended through the remainder of 2022, with payments resuming January 1, 2023. President Biden also proposed $20,000 in forgiveness for Pell Grant recipients and $10,000 for others (income-capped), though legal challenges delayed the implementation.

- October 2023: Payments on federal student loans resumed after the pause ended, with a 12-month “on-ramp” period (through September 30, 2024) shielding borrowers from credit reporting of missed payments, though interest accrued.

One well-discussed consequence of the government’s pandemic-era interventions was a spike in inflation, which the St. Louis Fed quantified in a study looking at inflation in February 2022. That study found that 2.6% of the 7.9% 12-month inflation rate in that month was the result of stimulus payments leading to substantially more demand for goods than industrial production could supply.

Another consequence of the government’s actions during the pandemic, which has been much less discussed, was the inflation in consumers’ credit scores.

According to the New York Fed, student loan borrowers saw an 11-point increase in median credit scores from the end of 2019 to the end of 2020, as a result of the CARES Act. This effect was even more pronounced for borrowers who had student loans in delinquency (but not default), which the CARES Act marked as “current” (i.e., not delinquent). These borrowers saw an immediate jump in their credit scores of 74 points on average (from 501 to 575), and increased gains after that as other, older negative information on their credit files aged off (negative tradelines drop off after 7 years).

And then, in 2022, we had the Fresh Start program, which was designed to help federal student loan borrowers in default (who didn’t benefit from the CARES Act the way that delinquent borrowers did). The Fresh Start program changed the status of roughly 1.9 million borrowers’ student loans from “defaulted” to “current”. According to an analysis by the CFPB, this change didn’t have any effect on these borrowers’ delinquency rates on other loan products, which makes sense as most other loan products didn’t have the same interventions that student loans had. However, it did have a large and immediate impact on these borrowers’ credit scores, causing them to shoot up by an average of 54 points between September 2022 and December 2022.

And here’s the most interesting part — this artificial increase in consumers’ credit scores, which was concentrated among consumers with lower incomes and subprime credit scores, was framed by the Biden-era CFPB as a good thing:

Credit score increases that move people into higher credit score tiers may increase their access to credit and result in new credit access at lower interest rates. Many borrowers whose credit scores increased following Fresh Start still have low credit scores and limited access to credit, but now more than 25 percent of those borrowers have a near-prime score or better, as compared to less than 8 percent before Fresh Start. Such score increases may result in substantial decreases in interest costs for borrowers. For example, this sort of change might correspond to $1,700 in interest savings for a typical auto loan, holding everything else the same.

I find this framing deeply problematic, and I want to explain why.

Number Go Up

There are many reasons why consumers’ credit scores increased during and immediately after the pandemic.

Student loan forbearance programs were a big one. However, during those years, we also had mortgage forbearance programs, stimulus payments (which many consumers used to pay down credit card debt and build up savings reserves), and a more financially cautious attitude among consumers.

I want to be clear — in the early stages of the pandemic, these government interventions were completely justifiable. It was a once-in-a-century global pandemic. No one knew how long it would last or what the economic effects of it would be. It was worth overreacting to, even if that overreaction did cause some price and credit score inflation.

However, by the middle of 2022, the it’s-worth-overreacting-because-we-don’t-know-what-will-happen way of thinking was becoming more difficult to justify. The effects of the pandemic had moderated, thanks to the vaccine. Employment, consumer spending, and business investment were all relatively healthy. Stimulus had mostly wound down, and the Fed was just beginning to raise interest rates to combat inflation.

At this point, there was really no justification for continued student loan interventions as a response to COVID-19.

However, if your goal was to correct a perceived unfairness in our credit scoring system, you might have been intrigued by the idea of giving a small group of economically disadvantaged student loan borrowers a “fresh start.”

I can empathize with that desire. However, as I frequently write about around here, just because you can push a button and magically make someone’s credit score go up, it doesn’t mean that you’ve actually changed anything fundamental about their financial situation or their ability to handle credit obligations.

If you look at the data, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that all of the government-induced credit score inflation we’ve seen over the last 5 years has meaningfully changed consumers’ financial behaviors or circumstances.

At the end of 2024, the official share of delinquent or defaulted student loans (according to the credit bureaus) was 1%.

However, once payments on federal student loans resumed in October 2023, there was no reason to assume that delinquencies wouldn’t return to their normal levels as well, even if they weren’t being reported to the credit bureaus. And indeed, that is exactly what has happened! According to the New York Fed, the actual delinquency rate on student loans is now estimated to be more than 15%, which would exceed pre-pandemic levels.

And now that the “on-ramp” period that restricted furnishing repayment data to the credit bureaus has ended, we will start seeing consumers’ credit scores tank. Hence, this chart, which I shared at the beginning of this essay:

Again, this makes intuitive sense. We saw a similar pattern in the credit card space. Credit card balances and delinquencies dipped significantly during the pandemic because consumers had more money in their bank accounts thanks to stimulus checks. When that extra money ran out, consumers’ credit card balances and delinquency rates returned to (and then surged past) pre-pandemic levels.

Making a consumer’s credit score go up doesn’t, by itself, change their behavior or circumstances.

And yet, whenever we (as an industry) debate a topic that could impact consumers’ credit scores (rent reporting, medical collections, BNPL, etc.), many consumer advocates insist that we start with the principle of “do no harm”.

Mixing Credit Scoring and Public Policy is a Bad Idea

The credit bureaus are far from perfect. Their data is rife with inaccuracies. Their systems are easy for fraudsters to manipulate. They make it incredibly difficult for consumers to dispute, correct, or freeze their credit reports. And because their core product is commoditized, it’s trivially easy to make them compete against each other and agree to do things that even they know they shouldn’t do.

I say all of this to make this point clear — I understand where consumer advocates are coming from when they criticize the credit bureaus and the impact that their negligence can have on financially vulnerable consumer segments. And I understand why consumer advocates are naturally suspicious when anyone pitches any idea for changing, improving, or adding to the data held by Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion.

That said, when those ideas are pitched, consumer advocates almost always respond by encouraging regulators and legislators to enact them in a way that prioritizes preserving or strengthening consumer access to affordable credit over giving lenders the best data to make credit decisions.

In other words, the goal is to make consumers’ credit scores go up (or at least ensure that they don’t go down).

This is the animating idea behind the National Consumer Law Center’s focus on reporting only positive rental data to the credit bureaus:

The most important consideration is that rent reporting should be limited to positive payment information only. Programs that report negative or “full file” information will most certainly harm vulnerable, struggling families.

And the exclusion of medical debt from credit reports:

Banks and lenders are not the ones to lose from a ban on medical debts on credit reports. In fact, the financial services industry could benefit from a ban as more consumers become eligible for mainstream credit. Removing medical debts from credit reports benefits consumers tremendously. The CFPB’s research found that consumers experience a 25-point increase in their credit score after the last medical debt is removed from their credit report, and that they have access to thousands more in available credit afterwards.

And the argument for how BNPL repayment data should be captured and categorized by the credit bureaus:

If buy now, pay later credit is reported as a series of individual six-week loans that are opened and closed in a short period — which is how most BNPL lenders characterize their products — many of these factors will end up hurting a credit score.

However, if BNPL lenders reported all their loans to one consumer as a single revolving, open-end account, the product could potentially help a consumer’s credit score based on these same factors.

These issues are complex, and on each of them, I share at least some of the same concerns that the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC) has. The impact of negative rental reporting on housing security is a legitimate and serious concern. The use of credit bureau furnishing as a cudgel by collection agencies in the medical debt space is, of course, troubling. And the question of how to best capture BNPL data in credit reports does not have an easy or obvious answer.

It’s tempting to address these concerns by applying direct pressure (rulemaking, supervision and enforcement, PR campaigns, etc.) to the credit bureaus. After all, it’s a highly concentrated market with lots of coordination between the three big players. Getting even one of them to do what you want can have a huge positive impact on consumers. And because the credit bureaus are naturally unsympathetic figures in the public consciousness (massive corporations that harvest your data without your permission) that are constantly screwing up (the 2017 Equifax data breach being the best example), they have a very difficult time lobbying against these policy initiatives, espcially when those initiatives are framed as helping consumers preserve or improve access to affordable credit.

No one wants to make the argument that the most important job of the credit bureaus is to enable lenders to make accurate credit decisions that comply with fair lending laws, and that, as tempting as it is, we shouldn’t use the credit bureaus to advance other public policy goals that might compromise that prime directive.

Luckily, the next big innovation in lending will make it structurally difficult to mix credit scoring and public policy.

Cash Flow Data is Censorship-Resistant

In a webinar that I hosted this week on cash flow data, my friend Tim Bates (who is the author of a wonderful report on cash flow underwriting, BTW), was talking about how powerful cash flow data can be as a complement to traditional credit bureau data and he said something that really resonated with me.

He said that compared to traditional credit bureau data, cash flow data is relatively assumption-free.

What he meant is that with cash flow data, sourced directly from consumers’ bank accounts, what you see is what you get. It’s a messy, badly structured, real-time look at a consumer’s financial life. It can be difficult to parse, extract insights from, and make decisions on, but the data itself has this almost atomic-level honesty. There are no assumptions built into it.

Traditional credit bureau data has lots of assumptions built into it.

For the most part, this is a feature, not a bug. Credit bureau data is extremely well structured. It’s easy to understand and make decisions with. The credit bureaus and FICO have worked for decades with lenders to build a shared understanding of how to think about and apply this data.

This arrangement works great, as long as all of those layers of assumptions are based solely on the goal of making accurate credit decisions that comply with fair lending laws.

However, as soon as you start inserting other public policy goals and changing how data is furnished to and stored by the credit bureaus, you have a problem.

Let’s go back to the Fresh Start program. By converting the status of 1.9 million borrowers’ student loans from “defaulted” to “current”, you can quickly increase their credit scores (by an average of 54 points), but are you actually improving those consumers’ willingness and ability to repay loans?

No!

In the summer of 2022, the federal government made it significantly more difficult for lenders to understand the risks posed by those 1.9 million people. That was a disservice to those people.

Lenders aren’t stupid. When the data they rely on to make accurate credit risk decisions gets disrupted, they don’t shrug their shoulders and just keep lending money. They stop trusting that data. They tighten their credit boxes. They protect themselves.

And the consequence is that they stop trying to parse out good risks from bad risks in a nuanced way. They just pull back from serving that entire customer segment.

This is exactly what has happened with credit builder products over the last couple of years. The credit bureaus stupidly decided to take data from fintech credit builder products, even though those products weren’t producing reliable willingness-to-pay signals. Lenders noticed and adjusted their underwriting models to screen out or (in a few cases) punish consumers with fintech credit builder tradelines. Responsible consumers who just wanted to improve their scores ended up getting declined for loans, even though their scores had ostensibly gone up.

The beauty of cash flow data is that it can’t be gamed this way. There are no centralized companies collecting and organizing the data that you can trick or pressure to make consumers’ credit scores go up.

The data is shared directly by consumers, on an individual basis, each time they want to get a loan. The data provides a real-time window into what is actually happening, on the ground, with the consumers’ financial situation. No assumptions. Just the messy, unvarnished truth.

To put it another way (which will sound familiar to those of you working in crypto) — cash flow data is decentralized, and because it’s decentralized, it’s censorship-resistant.

Until recently, I had not appreciated how important censorship resistance is in lending.