Chime, the newly public neobank, is aiming to capture primary financial relationships with the 227 million Americans who earn $200,000 or less annually.

This is a company that isn’t really a bank in any recognizable way. No charter. No branches. A very narrow product set. A business model that eschews net interest margin. And, most importantly, Chime appears to have zero interest in ever becoming more like a traditional bank, in any respect.

And yet, the company’s North Star is the exact same one that every bank has been aiming at since the beginning of time: primary financial relationships.

Here’s how Chime describes it in its S-1:

We designed our business to develop primary account relationships with our members, establishing Chime as their central financial hub. As we become the platform through which members deposit their paychecks and conduct their everyday spending, we create durable and long-lasting relationships with high engagement. We believe the primary account relationship is vital and enables lifetime value – the average tenure of a primary deposit account at a traditional bank or credit union is estimated to be between 16 and 24 years. We have now earned the trust to serve 67% of our 8.6 million Active Members in a primary account relationship as of March 31, 2025. … When we serve our members in a primary account relationship, we earn deep and habitual engagement and “top-of-wallet” card spend for their everyday, largely non-discretionary expenses. … These relationships also provide a privileged repayment advantage for liquidity products and rich, first-party data, including member income, spending, transaction, social graph, and other engagement data, which enables product innovation. As we expand our platform offerings, we believe these relationships will help drive Active Member growth, position us well to continue to cross-sell additional products, and improve our Average Revenue per Active Member.

Chime’s executives clearly think that the company can beat banks at their own game — not only going after its original target segment of consumers making less than $100,000 a year, but moving upmarket to consumers making up to $200,000 a year — and doing so without many of the tools that banks have traditionally relied on.

That undoubtedly strikes many bankers as optimistic to the point of delusion, and they may be correct. Maybe Chime is delusional. Or maybe it understands something that many banks have failed to appreciate — when it comes to primacy, the game has changed.

A Quick Primer on the History of Primacy

To understand the fight over primary financial relationships, we must first examine the evolution of the concept of primacy in the financial services industry.

In the United States, I believe that evolutionary history can be divided into three chapters.

Chapter 1: This Town Isn’t Big Enough For Both of Us (Primacy is the Default)

For most of the 1900s, banking in the U.S. was geographically restricted. In the early part of the century, most banking took place through “unit banks”, that is, independent banks with no branches. Even as states began to relax their laws and allow in-state branching (the same bank operating multiple branches), they still restricted out-of-state banks from entering their markets, and the McFadden Act prevented nationally chartered banks from interstate branching.

In those days, banking was hyper-local. Primacy wasn’t earned. It was bestowed upon you with your charter. Switching costs were enormous — physically schlepping paper statements, re‑routing payroll checks, and enduring the small‑town glare that came with breaking up with the local banker. Unsurprisingly, churn in those days was minimal.

Banking wasn’t competitive or especially convenient (though bank customers didn’t know that because they had never experienced anything else). However, it was highly personalized. Most interactions with your bank took place face-to-face, either in the branch or out in the community where you and your banker both lived. They knew you. And you trusted them.

Chapter 2: Get Bigger and Sell More (Wallet Share = Primacy)

In the 1980s, states began to relax their restrictions on out-of-state branching, and in 1994, the Riegle‑Neal Act legalized interstate banking at the federal level.

Suddenly, the incentive for banks was to get bigger, both in branch footprint (bank M&A accelerated significantly in the 1990s and early 2000s) and in breadth of products (this period marked the emergence of “universal banking” where large banks aspired to offer customers every product they could conceivably need under one roof).

The theory of primacy in those days was that you needed to get your customers to buy as many of your products as possible. The more products per customer, the stickier those customer relationships were thought to be.

This vision of primacy was problematic because it wasn’t oriented around customer value. The big banks weren’t trying to win by offering competitive pricing, personalized service, or differentiated individual products.

Instead, they were trying to win by giving customers the “convenience” of getting all of their products from a single provider. Or, to put it in more accurate terms, they were trying to construct bundles that would be prohibitively inconvenient for their customers to disassemble.

And as Wells Fargo dramatically illustrated with its “eight is great” initiative, they often went to extreme lengths to tie those bundles around their customers.

Chapter 3: The Era of Unbundling (Primacy is Dead)

Even without Wells Fargo flagrantly breaking the law, it’s unlikely that banks’ brute-force approach to cross-selling and primacy would have been sustainable.

The simple reality is that there is no amount of artificially created switching inconvenience that can’t be overcome with technology.

Ohh, you think the density of your branch network precludes any major competitors from poaching your customers?

Digital account opening will allow any competitor to reach your customers at any time.

Ohh, you believe you know more about your customers (their history, habits, and preferences) than anyone else ever could?

Open banking will enable customers to share their data with any organization they choose.

Ohh, you aren’t worried about offering undifferentiated products because there aren’t that many banks out there, and all of them offer the same undifferentiated products?

Banking-as-a-Service will create a seemingly infinite number of niche competitors, each offering specific, highly compelling products and services.

Put simply, technology enabled fintech startups to unbundle the universal banking model.

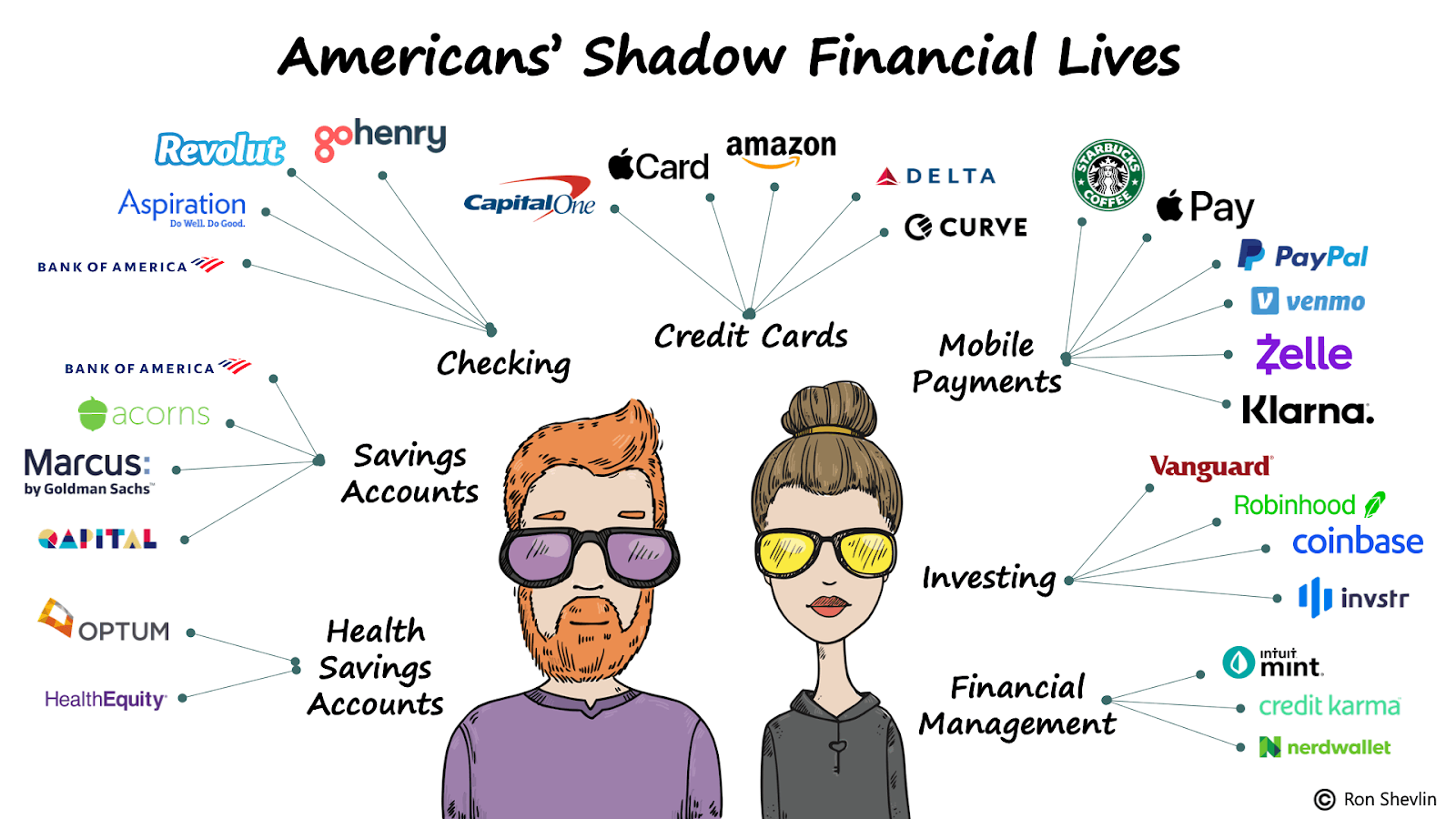

This has been the story in financial services for the last decade or so, and it has led to some fundamental questions about the very concept of primacy. Here’s what my friend and former boss, Ron Shevlin, wrote on the subject back in 2021:

Americans’ financial lives have become more complex. The proliferation of fintech providers has expanded the number of providers that consumers have accounts with, and — perhaps more importantly — the number of tools consumers use to manage those accounts.

We don’t see it very often anymore, but not long ago banks urged their consumers — to no avail — to consolidate their accounts at that institution. Gotta wonder if those banks really understood the futility and complexity of those exhortations.

The proliferation of fintech tools has unbundled traditional financial products. While the startups behind these tools have generated strong interest and engagement, they are, for the most part, product (even “feature”) — not solution — providers.

I think that’s exactly right. Financial services is now an open ecosystem. Any company can offer a financial product. Any company can get permission to access a consumer’s financial history. Any company can compete with any bank, regardless of the banks’ physical locations.

The question is, what does this new environment mean for the idea of primacy?

Do consumers still have primary financial relationships? Does that concept still make sense?

Or is it hopelessly antiquated? Are we hurtling towards a future in which consumers orchestrate their financial lives across dozens of different apps, with no thoughts of loyalty or brand affinity entering their minds at all?

Is Primacy Dead?

Perhaps I’m delusionally optimistic myself, but I don’t think so.

I believe the concept of primary financial relationships remains a valid one. I think consumers still think (and want to continue thinking) in these terms.

There are two reasons I think this.

First, we are already seeing signs that consumers are using fewer finance-related apps than they had been, indicating a desire to rebundle rather than to remain fully unbundled. Here’s MX, citing a recent survey of 1,000 U.S. adults:

Our research shows a clear indicator that consumers are also consolidating the number of finance-related apps they use. In less than 6 months, the percentage of consumers who have 3 or more finance-related mobile apps on their phone has dropped 7 points to just 40%. Among those who have 3 to 5 apps, the decline is 5 points in the same timeframe.

Most consumers (44%) say they only have 1 to 2 finance-related mobile apps currently downloaded to their mobile phone.

Second, although it has never been easier to switch banks, and a reasonably large percentage of consumers say they are open to switching or are likely to do so soon, few actually end up switching banks.

There’s a lot of data that substantiates this phenomenon.

According to a Deloitte survey of 3,001 U.S. consumers, more than half of all respondents reported that they’d had their primary checking account with their current bank for more than 10 years.

More recently, J.D. Power found that despite consumer trust in retail banks declining significantly over the past two years (due to unexpected fees, poor customer service, and bad press) and 13% of survey respondents saying they “probably will” or “definitely will” switch banks in the next 12 months, only 8% actually did change their primary bank over the previous year.

And in the UK, where the government operates a service — the Current Account Switch Service — that is expressly designed to enable consumers to switch from one payment account provider to another in 7 days, only 1.19 million consumers switched bank accounts in 2024, which represented just 2.5% of eligible UK adults (by contrast, 12-15% of UK consumers move energy suppliers and 7-9% switch mobile phone carriers).

So, when it comes to primacy, where does all of this leave us?

I have three observations:

- Inertia is a real, but slowly diminishing, force in banking.

- Convenience is the most obvious part of a winning strategy, but it’s not the whole thing.

- Primacy, as a concept in financial services, is more complex than we tend to assume.

I would like to elaborate on each of these points, starting at the end and working backwards.

Primacy is Complex

The most direct way to understand what drives primacy in financial relationships is to just ask the consumers who are in those relationships.

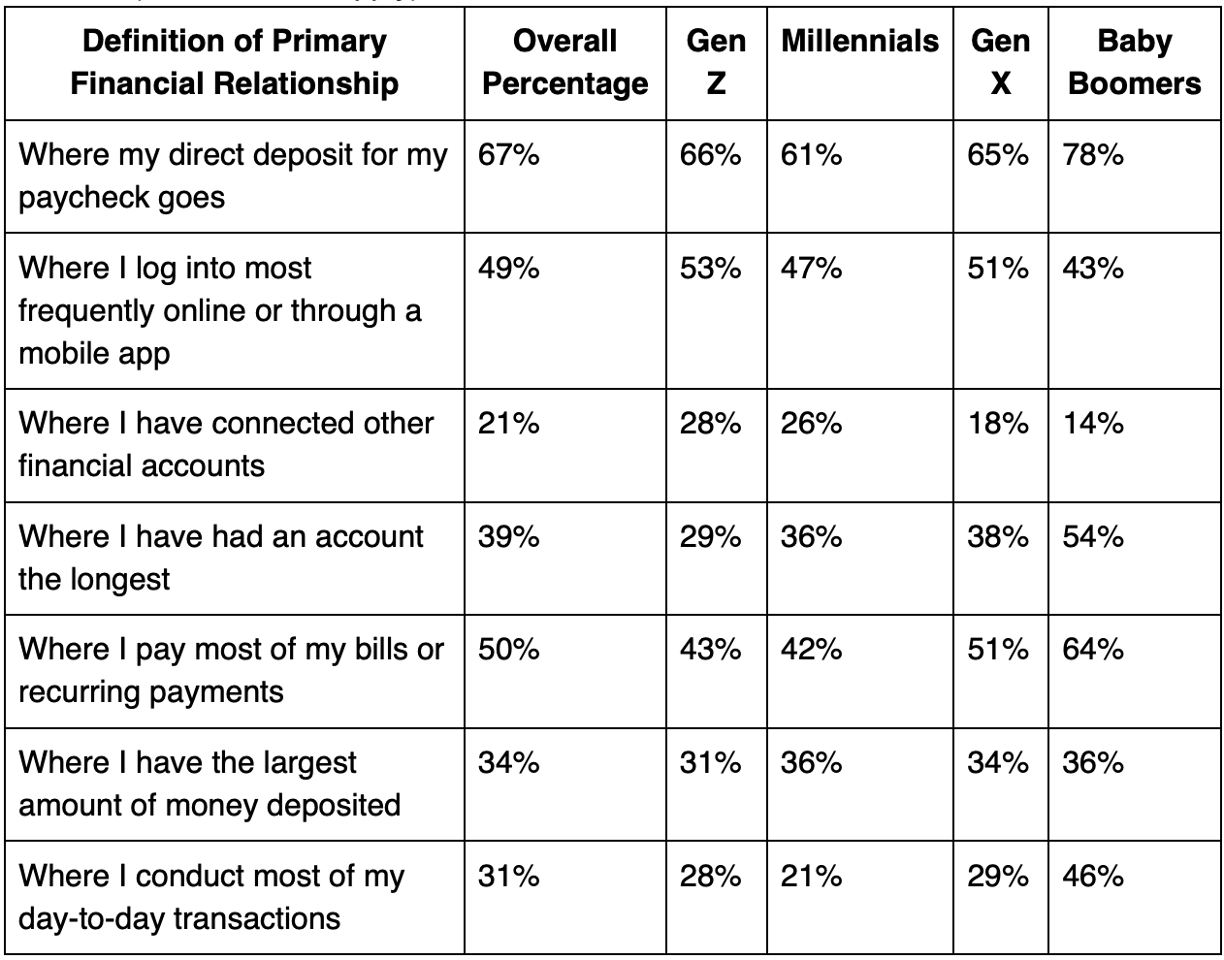

MX did this in a recent survey, asking, “Which of the following best describes how you would define a primary financial relationship?”

Here are the results:

A few things jump out:

- The top three drivers for primacy are direct deposit, bill pay, and digital engagement. This makes sense. If I had to predict a top three, these would have been the three I’d have picked: money in, money out, and careful monitoring of the account. This combination is what bankers would describe as an “operating account”.

- Gen Z being significantly higher than Baby Boomers on “Where I log into most frequently online or through a mobile app” and “Where I have connected other financial accounts” did not surprise me. Those are the responses that most directly map to the use of fintech, which tends to be higher among younger consumers. Also notable in those two categories was Gen X being higher than Millennials on “Where I log into most frequently,” but much closer to Baby Boomers on “Where I have connected.” Gen X, as always, proves difficult to pin down!

- Baby Boomers were much more likely to associate the length of the account relationship with primacy than younger generations. I wonder what is driving that finding? Do Baby Boomers believe that they get better or more personalized service from financial services providers who have known them the longest? Why is there such a big gap between Boomers and both Gen X and Millennials on this one?

- It’s notable to me that the answer that most closely maps to banks’ core business model (“Where I have the largest amount of money deposited”) is among the least correlated with primacy, across all generations. Yet another reason to worry about the future of net interest margin.

Overall, the takeaway from this data is that while many of the factors driving primacy make intuitive sense, there is no one silver bullet for establishing primary financial relationships, and such relationships are assured to change over time as consumers age into different life stages.

Convenience Wins, But Not Alone

An easy rule of thumb for predicting what will happen in financial services (and in life, generally) is that convenience always wins. It’s a truism that’s rooted in basic human psychology.

People prefer easy to hard.

It’s why digital account opening has overtaken branch-based account opening for essentially every product and account type in financial services. And it’s why, all things being equal, consumers prefer to have fewer finance-related apps on their phones, rather than more, as the earlier MX survey data indicated.

However, a common mistake that I see companies in financial services (particularly fintech companies) make is assuming that convenience is the only thing that matters and optimizing exclusively for it in their products and business models.

To give just one example: if convenience were the only thing that mattered to consumers when picking a new bank account provider, then why is “branch proximity” consistently one of the top factors that consumers say is important in making that choice, even though most consumers rarely visit branches?

From the Financial Brand:

For consumers, bank branches offer everyday convenience to do transactions, the ability to speak to a professional in-person, but importantly, provide a sense of safety even if they never visit. According to Rivel’s November 2024 National Pulse Survey, 52% of consumers have visited their primary bank’s branch between 1-4 times in the past 12 months. Baby Boomers lead this national data set with an average of 4.6 visits per year, while Gen Z is lowest at 3.6 visits.

However, Rivel’s research also reveals that 69% of consumers prefer a branch within 15 minutes of them to consider switching to a new institution. Surprisingly, this strong desire is remarkably equal across ages and income levels as well.

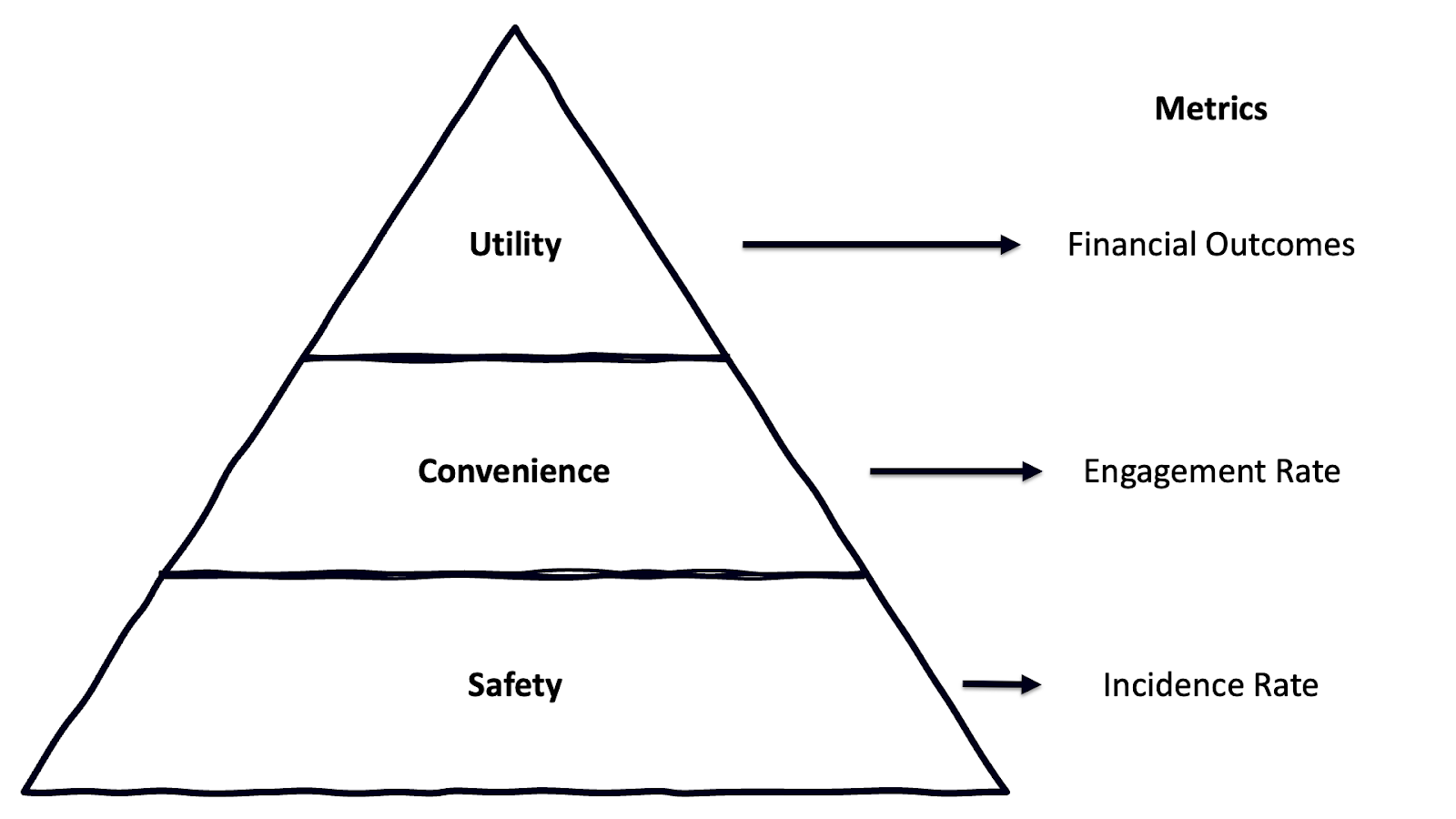

My theory on this — which I’ll call “Johnson’s Hierarchy of Banking Needs” — is that the fundamental needs that consumers have for bank accounts sit at different levels, and each level must be satisfied before the next one can be reached.

That hierarchy looks like this:

At the base of the pyramid is Safety, which is of paramount importance to all consumers. Above all else, they want to know that their money is safe. This encompasses everything from FDIC insurance to cybersecurity to protection from fraud and scams.

One layer up, we have Convenience, which, as we’ve already discussed, is deeply important to all consumers and is an overwhelmingly important factor guiding their day-to-day financial decisions.

And finally, at the top level, we have Utility.

What I mean by utility is the ability for a financial product or account to help a consumer meet their long-term goals. Those goals could be anything from getting out of debt to establishing healthy financial habits to building wealth.

This framework helps explain why branch proximity remains weirdly important to consumers of all ages, despite the declining role of the branch in facilitating day-to-day financial transactions: branches function as a psychological safety net for consumers; a shorthand way of estimating how risky it is to trust a company they don’t really know with their money.

This framework also helps explain why many fintech companies over-optimize for convenience — it’s the one that’s easy to measure.

The feedback loop is tight. You build the product, ship the mobile app, and measure how frequently your customers engage with it. The higher the engagement rate, the more convenient you can assume your product is to use and get value from.

By contrast, the feedback loops for safety and utility are much longer and much less predictable. You can build stuff in financial services that is wildly unsafe, but unless everything breaks in the exact wrong ways (as it did with Synapse), your customers might never realize it.

Similarly, a lot of the financial outcomes that consumers hope to achieve through the utility of the products they use don’t manifest overnight. Indeed, given the importance of slow-burn phenomena like compounding interest in financial services, it’s almost impossible to build a rapid feedback loop to measure the utility of many financial products.

None of this means that safety and utility aren’t important factors underpinning primary financial relationships. They are. It’s just that they are difficult to measure and, as the old saying goes, what gets measured gets managed.

Despite that, my theory is that, over time, utility will become the layer of Johnson’s Hierarchy of Banking Needs where most competitive differentiation accrues. Safety in banking is table stakes (as fintech is slowly learning), and convenience is quickly becoming table stakes as well (as convenience becomes a function of digital capabilities and design rather than physical proximity, it becomes an easy value prop for competitors to replicate). Once those needs are satisfied, consumers will seek out financial services providers who can help them meet their goals and gracefully navigate the different stages of their financial lives.

Inertia Will Slowly Go to Zero

You can’t explain the success, historically, that banks have had in retaining their customers and discouraging switching without talking about inertia.

By inertia, I mean that a primary financial relationship set in motion will tend to stay in motion.

It is a remarkably powerful force in the financial services industry.

However, I firmly believe that inertia, as a force in banking, is diminishing and that, eventually, it will cease to be a significant factor in determining the stability of financial relationships.

Once again, we have technology to thank for this. Specifically, agentic AI:

These AI agents might be a bit inexperienced and overeager (sometimes they will lie or get stuff wrong), but they will be relentless in their pursuit of optimal outcomes, and they will have a level of general intelligence and capability that we’ve never seen before.

How will consumers and companies use them?

They will use them to do things they can and should be doing today but are too lazy to do.

That has the potential to break a lot of business models that depend on laziness or uninformed decision-making, including net interest margin.

My favorite way to conceptualize what this will look like in banking is to picture little ‘rate optimization robots’ roaming around the market, working on our behalf, constantly trying to refinance our loans and increase our deposits APY.

When rates move, bank customers will move … instantly. Price discovery will become perfect, and product utilization will become fully optimized.

Any business built on customer inertia will, eventually, go to zero.

How to Win Primary Financial Relationships and Influence the Bottom Line

Primacy remains a significant force within the financial services industry, although it is now more complex and uncertain than it was in the past.

Primary financial relationships are still worth going after — in fact, 80% of consumers say they have one, according to MX. However, the strategies banks employ to go after them must evolve to keep pace with changing consumer expectations and competitive dynamics.

Here are three strategic recommendations for banks to consider:

1.) Tie Convenience and Utility Together

We must vehemently reject the notion that building engaging financial products and building financial products that help consumers reach their long-term financial goals are mutually exclusive.

That’s dumb. That would be like saying that the only way to enjoy basketball (objectively the world’s greatest sport) is to sit on the couch and play FanDuel while watching a game. Wrong! You can also play in a pickup basketball game!

Both are engaging, but only one is going to make you healthier.

Products built to deliver positive financial outcomes for consumers can also be convenient and engaging to use. Indeed, the easier and more fun they are to use, the more that customers will use them, which drives a virtuous cycle of improvement for both the customers’ and the bank’s bottom lines.

This is precisely what MX found when it studied the relationship between consumers’ use of financial wellness tools and the financial results for them and their banks:

Consumers who regularly engaged with MX’s personal financial management (PFM) features — specifically creating and using budgets — within their mobile banking experiences had the highest deposit levels and grew those balances during the year, even as deposit balances fell for those who didn’t engage as often.

While growing their deposit balances, these users also managed their credit card debt more effectively than others, even during a period of high inflation and increasing consumer debt levels.

With the insights generated from these tools, consumers are able to spend less than they earn, build up their savings, and avoid debt — all of which drive improved financial wellness for the consumer and in turn, better outcomes for the financial institution.

2.) Focus on Operating Accounts

Remember, money in, money out, and careful monitoring of the account. These were the three most common contributors to consumers’ perception of primacy, according to MX.

Or, as one banker, whom I spoke to while researching this essay, eloquently phrased it, “primacy is payments.”

However, to earn the right to handle payments for consumers, banks must build operating accounts that help consumers manage their finances. This goes well beyond the standard checking account, which has become a deeply commoditized product.

Here’s the ever-prescient Ron Shevlin again:

Checking accounts have become paycheck motels — temporary places for people’s money to stay before it moves on to bigger and better places.

The problem is that — despite the slew of mobile banking features that keep coming out — the value that a checking account provides falls short of what consumers want and need.

[Consumers] need a “financial brain” — a way to manage the transactional aspects of their financial life.

The successor to the checking account will be service-focused, not just transaction-focused.

And in order to build the best operating accounts, banks must …

3.) Build for Specific Segments

The best operating accounts will be those built for specific customer segments. The days of mass-market, cookie-cutter product design are over.

In today’s digital-first environment, there is no reason why banks can’t build different bank account products for different target customer segments. These segments could be defined around geography, occupation, affinity, or life stage.

All that is required is a clear-eyed view into the unique functional needs of each segment and the infrastructure necessary to support a more granular approach to product manufacturing and distribution.

Capturing the Next Generation of Primary Financial Relationships

Chime got to 8.6 million active members by building more compelling products for consumers making less than $100,000 a year. Its next priority is to deepen those relationships and lock in primary status with those customers for the rest of their lives. And because of how the nature of banking has changed over the last 30 years, Chime doesn’t need branches or a banking charter to do it.

This puts banks in an urgent competitive position. As the era of unbundling comes to an end, an entire generation of primary financial relationships is up for grabs

Those relationships will be won by companies that rebundle financial services, not around convenience, but around utility.

Banks have an opportunity (and, indeed, are in an advantageous position) to win that competition, but it will require redefining what personalized financial services experiences look and feel like (hint: fewer branches, more data-driven digital interactions!) and building products that are tailored to the exact needs of their narrowly-defined target customer segments.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by MX.

About MX

MX Technologies, Inc. enables financial providers and consumers to do more with financial data. MX provides end-to-end solutions for financial institutions and fintechs to connect to, analyze, engage, and act on consumer-permissioned financial data.