Last month, I spoke at an event hosted by the Federal Reserve. The theme of the event was “Unleashing a Financially Inclusive Future”.

Within the first 15 minutes of my panel, we hit upon a key idea: “inclusion” might not be the right word to describe the problem that we are dealing with.

After all, if you look at the stats, we’re doing pretty well at ensuring that consumers who want to access the financial system can access it, efficiently and at a relatively low cost.

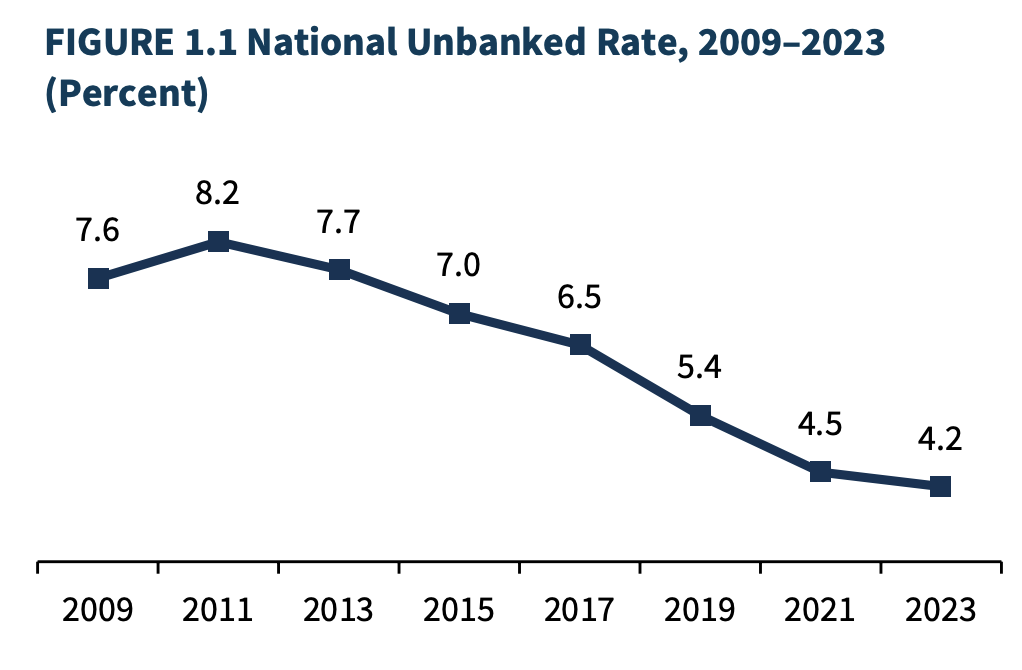

Here are the latest findings from the FDIC on the percentage of households in the U.S. that are unbanked:

And according to some recently revised data from the CFPB, the rate of credit invisible consumers in the U.S. — those with no record at the credit bureaus — is actually much lower than we thought:

In 2015, the CFPB released a widely cited report that provided a benchmark for estimates of consumers with limited credit histories. More specifically, the report included estimates of the adult population in the United States who, in December 2010, did not have a credit record (“credit invisible”) or who had insufficient credit history to have a credit score (“stale unscored” and “insufficient unscored”).

Subsequent analysis with updated data and a methodological correction reveals that the original estimate of credit invisibles should be roughly cut in half.

So, problem solved!

Right?

No. Obviously not.

First, just because we’ve improved access to our financial system doesn’t mean that the problem of inclusion is completely solved. We need to continue working to reduce the 4% unbanked number as close to 0% as possible (this is especially important because the rate of unbanked households is significantly higher among historically underserved segments, such as Black and Hispanic households).

And second, just because more consumers have access to the financial system doesn’t mean that access is translating into greater levels of financial resilience.

The CFPB’s revised numbers on credit invisibility are a great illustration of this.

Yes, the headline is that the number of credit-invisible consumers in the U.S. in 2010 was much lower (13 million) than we originally thought (25 million). However, that doesn’t mean that the consumers who make up the difference — roughly 12 million — had perfect (or even good) credit scores. According to the bureau, while those consumers did have files at the national credit bureaus (meaning that they technically had access to our credit system), their files were too thin or outdated to be scored (meaning that their access to the credit system was functionally irrelevant for the purposes of securing loans).

This duality — greater access without, necessarily, better outcomes — has prompted a question, which I have been obsessing over since the Federal Reserve event:

At a time of unparalleled access to financial products and tools, why does it feel like consumers have never been less financially resilient?

This is the question that I will explore in today’s essay.

Defining Financial Resilience

Before we go too far, we should define the term “financial resilience” because it’s important to know precisely what we’re aiming at.

Fortunately, my friends at ResilienceVC have already done a lot of work to define and measure financial resilience.

Allow me to quote extensively from their 2024 Annual Impact Report:

At its core, Financial Resilience is the capacity to withstand financial shocks and stressors and improve one’s economic position over time. It acknowledges that financial challenges are a byproduct of context and occasionally chance.

Financial resilience is driven by three key elements:

Net Income Generation

To build wealth, income must be greater than expenses. By increasing, diversifying, or solidifying income or revenue and managing one’s liabilities wisely, financial slack is created and financial improvement becomes realistic.

Risk Mitigation

Americans are at risk of the unexpected. Through innovative design and effective distribution, insurance and the development of adequate reserves mitigates the financial shock and impact of such risks.

Asset Building

One’s future financial position often depends on action today. Asset and core skill building enables adaptability and allows for returns on investments that are paramount to long term resilience and financial stability.

In my head, I think of these elements as being somewhat sequential. Generating revenue and controlling expenses create financial slack (AKA profit). Risk management protects that profit against financial shocks. And asset building invests that profit in long-term wealth generation.

Now that our definition is set, we can proceed to the next question: What is the state of U.S. consumers’ balance sheets?

The State of U.S. Consumers’ Balance Sheets

If we zoom out from the day-to-day noise and look at the whole of American household finances, one statistic jumps off the page: only three in ten U.S. households qualify as “financially healthy,” while the other 70 percent are either merely coping or outright vulnerable. That split, documented by the Financial Health Network’s 2024 Pulse report, has remained unchanged over the last two years, despite record-low unemployment and a booming stock market.

In other words, U.S. consumers are running fast just to stay in place.

We see the brittleness of consumers’ balance sheets most clearly in their liquid savings.

Or, more accurately, in their lack of liquid savings.

According to the Federal Reserve’s latest Survey of Household Economics and Decision-Making (SHED), only 63% of U.S. adults say they could cover a $400 emergency with cash or a cash equivalent (like an immediately paid-off credit card). This is down from 68% in 2021 (when consumers’ bank accounts were strengthened by stimulus checks) and back to pre-pandemic levels. The remaining 37% would have to borrow, sell something, or simply couldn’t pay.

Why, you might ask, has this metric not improved, despite consistent growth in wages since the pandemic?

It’s true that wages have been rising. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (shoutout to independent economic data!), median weekly earnings for full-time wage and salary workers in the U.S. reached $1,196 in Q2 of this year, nearly 5% higher than Q2 of 2024.

And yet, in parallel, 68% of Americans — across all income brackets — report living paycheck to paycheck, according to a PYMNTS survey.

The PYMNTS paycheck-to-paycheck survey data, which has been collected consistently for the past five years, has been a steady source of fascination for me because it captures the two fundamental reasons why a consumer might live paycheck-to-paycheck: choice and circumstance.

According to PYMNTS data, 21% of consumers live paycheck to paycheck primarily out of necessity, 54% due to a combination of choice and circumstance, and 25% largely by choice.

The circumstances side of the equation is fairly straightforward. If you don’t make enough money to consistently pay for basic necessities, you will have difficulty paying your bills on time. Obviously, this problem predominantly affects low-to-moderate income consumers, and it has been compounded, in recent years, as those basic necessities have become more expensive.

According to the BLS, between December 2023 and December 2024, overall inflation cooled to 2.9%, but many of the categories of spend that ordinary families can’t avoid kept getting more expensive — shelter costs were up 4.6%, motor-vehicle insurance 11%, and hospitals (and related services) 4%. In other words, the stuff you have to buy has stayed stubbornly expensive, quietly absorbing most of those bigger paychecks before they hit savings accounts.

The other side of the equation is more interesting because it is more difficult to understand.

Why do a large percentage of consumers, across all income brackets, choose to spend (roughly) all of the money that comes into their checking accounts?

And, more importantly, how are merchants, billers, and financial services providers (banks and fintech companies) influencing those choices?

The Tyranny of Too Much Choice

Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein coined the term “choice architecture” to describe the way our environments shape our decisions. Defaults, menu order, and even the number of options all subtly influence our behaviors.

Twenty years ago, the average household’s financial choice architecture was so straightforward it was almost quaint: one checking account, one savings account, one or two credit cards, and a pile of paper bills due at the first of the month.

Today it’s … a bit more complex.

First, consider the raw surface area of possible choices.

According to most of the consumer survey data that I have seen (MX, Plaid, S&P Global), the average U.S. consumer regularly uses 2-3 different banking and fintech apps to manage their money, with a relatively large percentage (40%, according to MX’s data) using 3 or more.

Multiply that app sprawl by the boom in embedded-finance options that consumers are more and more likely to interact with — pay-by-bank buttons on e-commerce checkout pages, payroll cards from gig platforms, health-insurance wallets that auto-draft premiums — and you have a decision matrix that would test a comptroller, never mind a tired parent on a Tuesday night.

Second, many of these products are dynamic in ways that their predecessors weren’t, which creates an additional layer of complexity for consumers to manage

The revolving credit lines attached to credit cards are large, slow-moving debt obligations. They can be dangerous if managed poorly, but they are predictably dangerous. The payment cycles are consistent, the pricing and terms are standardized and well-regulated, and the scope of what they can pay for is broad (allowing consumers to roll up multiple payment obligations into a single monthly obligation).

By contrast, newer lending and liquidity products are much less predictable.

Take buy now, pay later (BNPL) as an example.

According to a survey done by PYMNTS at the end of 2024, 38% of U.S. consumers used BNPL, up from 24% the previous year. Notably, more than six in ten BNPL users reported holding multiple BNPL loans simultaneously. Each BNPL loan has its own repayment cycle (with differing numbers of installments and start dates timed to the individual financed transactions) and terms and pricing that are unique to the combination of the BNPL provider and merchant (meaning that there are tens of thousands of different possible permutations).

Another example is earned wage access (EWA), in which providers monitor consumers’ payroll or bank accounts to spot pockets of unused liquidity that they can advance to consumers. The funds can be delivered to the consumer instantly (for a fee), but the obligation follows right on its heels: repayment is pulled the moment the paycheck lands, tightening the next pay cycle’s margin for error.

Taken all together, the experience can easily become overwhelming. Decision theorists call it aggregation neglect: our tendency to underestimate how small, separate commitments add up.

And when you account for the differing speeds with which payments settle these days — ranging from weeks to milliseconds — the math gets brutal.

A Friday might now feature:

- a $125 BNPL debit for last month’s groceries,

- a $65 EWA repayment,

- a $30 streaming bundle renewal, and

- a landlord’s ACH rent pull at 12:01 a.m. Saturday.

Nothing in that sequence is illegitimate or even unreasonable, but together they can flip a balance from +$50 to –$220 in a matter of hours.

Two Different Visions of the Future

Here’s the question we need to wrestle with, as an industry: Is this future inevitable?

Are we destined, as consumers, to wander an increasingly fractured and fractious financial services landscape, dividing our money between different closed-loop wallets and accounts and grasping at every bit of liquidity that’s offered to us, whether we need it or not?

Or can we, perhaps, reach for a different future? One that benefits from the extremely high level of competition that we have today, while also drawing on some lessons from the past?

For example, I was speaking to a friend of mine who told me that when her parents were first married, her mom would gather up all of their bills at the start of the month and take them down to the local credit union. She would sit with someone at the branch to sort out a plan for the month: which bills to pay in which order, how much to save for other expected expenses that month, how much to save for the unexpected expenses, and what to do with the money left over (if there was any).

And while my friend didn’t mention this, it’s not hard to imagine, in this context, the credit union offering her mom a short-term loan if a large unexpected expense popped up. Or a little grace on an existing loan, if an unforeseen event like an illness or job loss temporarily sidetracked her ability to make her payment.

If we want a future for our industry defined not just by access, but by the financial resilience that consumers build once they gain that access, we need to find a way to bring a version of that experience — an integrated, customer-centric financial choice architecture — into our modern, highly competitive environment.

A New Playbook

The good news is that most of the building blocks needed to create this experience already exist in the market; the work ahead is to string them together into a coherent playbook.

Automated Liquidity Buffers

Remember, a fair definition of financial resilience acknowledges that financial challenges are a byproduct of context and occasionally chance. We can’t predict or control everything that might negatively impact a consumer’s balance sheet, nor can we prescribe to every consumer exactly what they should and shouldn’t spend their money on.

This is why having a liquidity buffer — something that can absorb those random $400 emergencies — is so important. The trick is automating the creation and use of a liquidity buffer, so that all consumers can benefit.

Fortunately, much of the plumbing necessary to build an automated liquidity buffer already exists. Digit (possibly my personal favorite fintech app ever) automated the sweeping of excess money from checking to savings. And a number of big banks have, in response to the market’s move away from overdraft fee revenue, introduced automated sweep capabilities going the other way: moving money from a linked savings account to checking to cover transactions that would otherwise be declined or trigger an overdraft.

Put those two together and you have a two-way, automated liquidity buffer.

Coordinated Bill Payment

It’s not just the amount of money that can flip consumers’ balance sheets upside down. It’s also the timing.

It’s always struck me as odd that banks, as a group, have never achieved significant traction in the bill pay space, particularly given the obvious potential that an integrated bill payment and liquidity management solution could have for consumers living paycheck to paycheck.

Many individual billers, particularly those in the utility sector, offer “pick-your-due-date” programs, which report higher customer satisfaction and lower arrears, as they allow individuals to align their bills with their paydays.

Why couldn’t a bank create a modern bill-pay hub that could redraw due dates, park money in a “bill reserve” for future payments, and even negotiate with individual billers (who, above all else, don’t want to close customers’ accounts) for short grace periods, where necessary?

Aligning bills with paydays (especially in today’s era of lumpier and more fractured income streams) can mean the difference between a smooth month and a cascade of overdrafts.

Intentional, Integrated Short-term Credit Options

The problem with overdraft protection, as it has been historically implemented, is that it is highly punitive for simple cash flow management mistakes (i.e., the infamous $35 cup of coffee example).

The problem with many of the alternative, small-dollar lending products offered by large fintech companies, such as Dave, Earnin, and Brigit, is that they are standalone solutions used in a siloed fashion, separate from the consumer’s primary operating account.

What’s needed is a small-dollar lending product that is integrated into the consumer’s primary operating account and designed to be used intentionally and sparingly, when liquidity is needed beyond what the consumer’s existing buffer can accommodate.

Fortunately, a quiet revolution has been happening in the bank-led small-dollar lending space over the last decade, which promises to make these products a table-stakes feature in the consumer bank accounts of the near future.

Better Visibility Into Discretionary Spend and Credit Usage

Better cash flow management and safer short-term lending options are a good start, but we can’t fully address the challenge of cultivating financially resilient customers without solving for the aggregation neglect problem I mentioned earlier.

Commerce, payments, and lending have become so tightly integrated in the last decade (and especially in the last five years since the start of the pandemic) that it’s now impossible to distinguish between the war for consumers’ attention and the war for their excess liquidity

(Editor’s Note — If you study certain rapidly growing consumer companies like Robinhood and Klarna, you will see what I’m talking about.)

The problem is that while each individual transaction (buying a memestock or financing a pair of shoes) can feel reasonable in the moment, the aggregate effect can be destabilizing and, over a long enough time horizon, devastating.

Banks can’t protect consumers from this war for their attention, but they can equip them with the insights and proactive recommendations necessary to navigate the battlefield responsibly. This requires data, which is why every bank should leverage open banking APIs to assemble a comprehensive, real-time view of their customers’ financial behaviors and obligations (including, especially, those not reported to the credit bureaus).

Payment Protection

Recall the second pillar in our definition of financial resilience: risk mitigation. Reducing the impact of unexpected financial shocks on consumers’ balance sheets and overall financial health.

This is a critical ingredient because, well, stuff happens. Job loss. Disability. Even death. These things are hugely disruptive, obviously. In an instant, they can erase months (or even years) of careful budgeting and saving.

Enter: payment protection insurance — an add-on policy that automatically covers your loan or credit-card payments when you can’t pay due to one of a specified set of events, so your account stays current and your credit record intact.

In a survey of 1,011 U.S. adults conducted by TruStageTM in March 2025, 85% of respondents reported worrying about keeping up with loan payments if a disruptive life event were to occur. When the concept of payment protection was explained, 82% said they would opt in — up from just 60% in 2023.

Reading through the verified comments from customers and members who have utilized payment protection insurance from TruStage (which I did while researching this essay), it becomes clear to me why it’s a popular feature:

“It gave me peace of mind in a challenging time.”

“I have been working for 27 years with the same employer – it was a relief to know there was help for me when I was let go.”

“Having this benefit helped me when I was out of work for surgery.”

Whether the trigger was heart surgery, a plant shutdown, or a crushed leg that kept them off work for months, the takeaway is identical: payment protection helped consumers convert a catastrophic cash-flow gap into a minor inconvenience.

Time to Shift the Conversation

It’s strange that we still spend so much of our time talking about financial inclusion, given that access to financial products and tools isn’t our most pressing problem anymore.

Perhaps we still focus on access because it’s easier to do that than it is to talk about what consumers are doing with that access.

And, more importantly, what they’re not doing with it.

And that’s a shame because we actually have many of the tools in place to help consumers who are inside the financial services perimeter build resilience.

And the payoff for doing so is immense.

Small-dollar loans originated inside the operating account are an efficient way to cultivate multi-product, deposit-rich customers. Predictive low-balance alerts cut both charge-offs and complaint volumes. Payment protection lowers default rates, creating a cascade of positive second-order effects.

Designing for resilience isn’t charity; it is the next big opportunity in consumer finance.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by TruStage.

TruStage is a financially strong insurance and financial services provider, built on the philosophy of people helping people. We believe a brighter financial future should be accessible to everyone, and our products and solutions help people confidently make financial decisions that work for them at every stage of life. With a culture rooted and focused on creating a more equitable society and financial system, we are deeply committed to giving back to our communities to improve the lives of those we serve. For more information, visit trustage.com.

TruStageTM is the marketing name for TruStage Financial Group, Inc. its subsidiaries and affiliates. Corporate headquarters are located in Madison, Wis.

LPS-8295389.1-0825-0927