Money and data have always been very closely related.

The idea that money is simply a number in a ledger rather than a physical thing that you carry around with you has existed in different forms for centuries.

However, since the first wire money transfer, conducted over long-distance electronic telegraph machines in 1871, money and data have been indistinguishable.

The creation of “electronic money” in the 1870s, followed by the creation of “digital money” nearly 100 years later, captivated entrepreneurs, who rightly saw the potential for technologies like the telegraph and computers to strip out a lot of the costs and inefficiencies from financial services.

This has been the axis upon which most disruptive innovation in financial services has been centered for the last 150 years, from Western Union to Venmo.

Curiously, it took society a lot longer to realize that if money is data, then data, by itself, is valuable.

When credit bureaus in the U.S. were rapidly consolidating and digitizing their operations in the 1950s and 1960s, the leaders of the industry were hauled up in front of Congress to explain what they were doing. Congress’s focus, at the time, was on protecting consumers’ privacy and other rights as the credit bureau industry moved from paper records to computer databases.

However, as far as I can tell, Congress never really questioned if the basic credit bureau model — get consumer data furnished to them for free and sell it back to lenders as a service — was fair or if, perhaps, consumers and lenders should be compensated for the data in some way.

Maybe Congress was still thinking about credit bureaus as they had been (community-based non-profits) rather than what they were becoming (large for-profit companies). Or maybe they thought the market for consumer data would never become that big.

Well, fast forward to today, and the combined market cap of the three national credit bureaus in the U.S. is nearly $100 billion. And they are only a small (highly visible) slice of the modern financial data economy, a market measured in the trillions of dollars.

The good news is that companies, regulators, and consumers have finally woken up to the reality that financial data is valuable, and all of them are vying to shape the future of the financial data economy.

In today’s essay, I will explore the trends and technologies impacting the financial data economy. I will propose a framework for how that economy should be structured in order to maximize value for consumers while protecting the legitimate business interests of the other participants. And I will make a few suggestions for how financial institutions and fintech companies should think about value creation and competitive differentiation in a world in which customer autonomy, data portability, and data recipient accountability are far more important than they have ever been.

The Financial Data Economy is at a Crossroads

To understand the current state of the financial data economy, we must first understand the competing interests of its participants.

Broadly speaking, these participants can be grouped into three buckets — Data Brokers, B2C Companies, and B2B2C Service Providers.

Let’s take a look at what is happening with each group.

Data Brokers

In simple terms, a data broker is a company that collects, organizes, and sells personal data about people to third parties. That data is often collected from public records, but not always. Data brokers are occasionally well-known companies like the credit bureaus, but often, they intentionally try to stay off the radar. Data brokers sometimes operate legally within well-defined regulatory frameworks, and sometimes, they operate illegally or in legal gray areas outside the regulatory perimeter.

The only things that data brokers have in common are that A.) they are not generally well-liked, and B.) they realized the commercial value of collecting and reselling data before the owners of that data did.

Unfortunately for data brokers, that era is over.

Companies, consumers, and regulators understand the value of consumer data, which has put the essential business model of data brokering — acquiring data cheaply and reselling it for more — under a great deal of strain.

Privacy has become a competitive differentiator in consumer products, which has reduced the availability of third-party data that can be acquired by data brokers. The most notable example is Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) framework, rolled out through iOS in April of 2021. This update required third-party app developers to obtain explicit consent from users before tracking their activities for advertising purposes (including selling their data to data brokers).

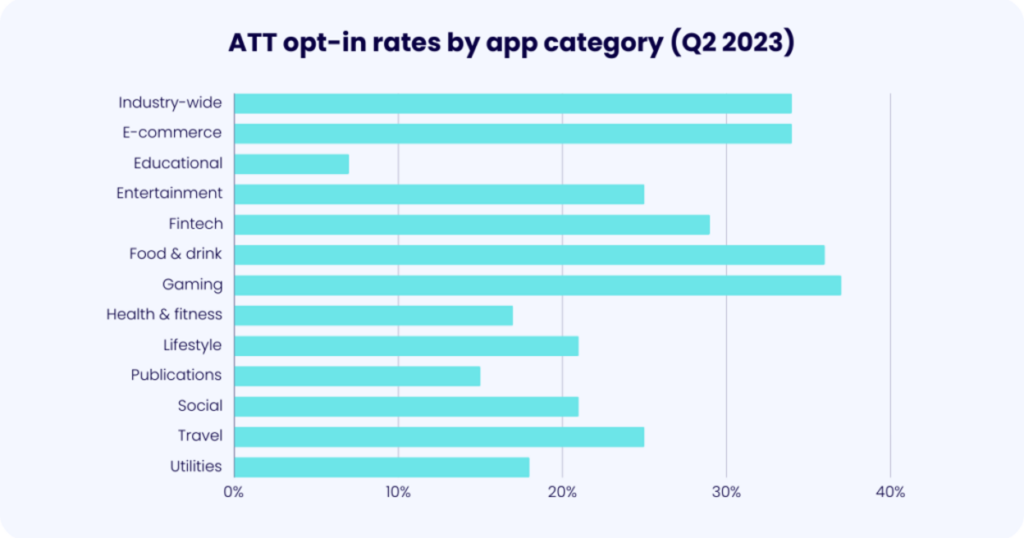

ATT has had a massive impact on the data economy by reducing the amount of third-party data available to data brokers and advertisers. While not as bad as companies initially feared, the opt-in rate by consumers (meaning the percentage that agree to allow their activities to be tracked) was only 34% in 2023, according to MAF. If you break that out by app category, fintech comes in at a paltry 29%:

Additionally, regulators have taken a keen interest in modernizing the rules around old data privacy and consumer protection laws, with the goal of curbing many of the modern practices of data brokers, which 20th-century legislators and regulators had no way of foreseeing.

The best example of this is the CFPB and its work to modernize the Fair Credit Reporting Act (which was the primary output of Congress’s hearings with credit bureau executives in the 1960s).

The FCRA was one of the world’s first data privacy laws, and it was intended to give consumers more rights and control over the data that consumer reporting agencies (the legal term for credit bureaus) were assembling and selling. The FCRA allows for certain sanctioned uses of consumer report data (i.e., permissible purposes, such as making credit, insurance, or employment eligibility decisions) but strictly prohibits other uses of the data. Additionally, the FCRA mandates certain accuracy requirements and gives consumers a right to see their data, and due process rights to dispute inaccurate or incomplete information in their files.

The CFPB, which has rulemaking authority in regard to the FCRA, believes that the FCRA has, by virtue of being more than 50 years old, failed to keep pace with the financial data economy it was designed to regulate. This has motivated the CFPB to undertake rulemaking to modernize the FCRA in several important ways, including:

- Expanding the definition of consumer reporting agencies (CRAs). The CFPB wants to expand the perimeter of the FCRA as much as possible. This would include all data brokers that sell data that is used for an FCRA permissible purpose (credit, insurance, employment eligibility decisions), whether they know that their data is being used that way or not, as well as all data brokers that sell data that is typically used for FCRA permissible purposes.

- Restricting the sale of consumer data. The CFPB also wants to ensure that FCRA-covered data is only sold for a permissible purpose or when a consumer grants their explicit written permission. Non-risk use cases for the data, like marketing (which is big business for the credit bureaus and other data brokers today), would be restricted.

- Making credit header data FCRA data. Credit header data is the identity data at the top of the credit file (name, address, DOB, SSN), which the credit bureaus have built a very robust business around for supporting non-FCRA use cases, such as marketing and fraud prevention. The CFPB is considering restricting the use of credit header data to only permissible purpose use cases, which would be a big (and unpopular) change.

- Limiting scope and giving consumers more control. The CFPB is very focused on making sure that buyers of FCRA-covered data only use the data for the narrow permissible purpose for which they got it and that consumers are empowered to more easily revoke authorization to use their data.

These changes, if they end up being finalized in the form that the CFPB has proposed, would have a massive impact on the financial data economy, curtailing many of the profitable activities of larger data brokers and running some smaller (and less reputable) data brokers out of business entirely.

For their part, data brokers argue that they provide an essential service for the market (and society, more broadly) by collecting and selling data — such as derogatory credit history — that consumers would never voluntarily share but is essential for the market to function efficiently.

There is some validity to this point, which I’ll touch on later in this essay.

B2C Companies

Here’s a theory that I can’t prove but believe in very strongly — if lenders in the 1960s (which were mostly retailers and banks) had understood the value of the data they were giving to the credit bureaus for free, they never would have agreed to do it, and Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion might not be names we recognize today.

If you are a sufficiently large, consumer-facing company operating today, you understand that the proprietary first-party data that you are generating through your transactions and interactions with your customers is one of the most valuable assets that you have.

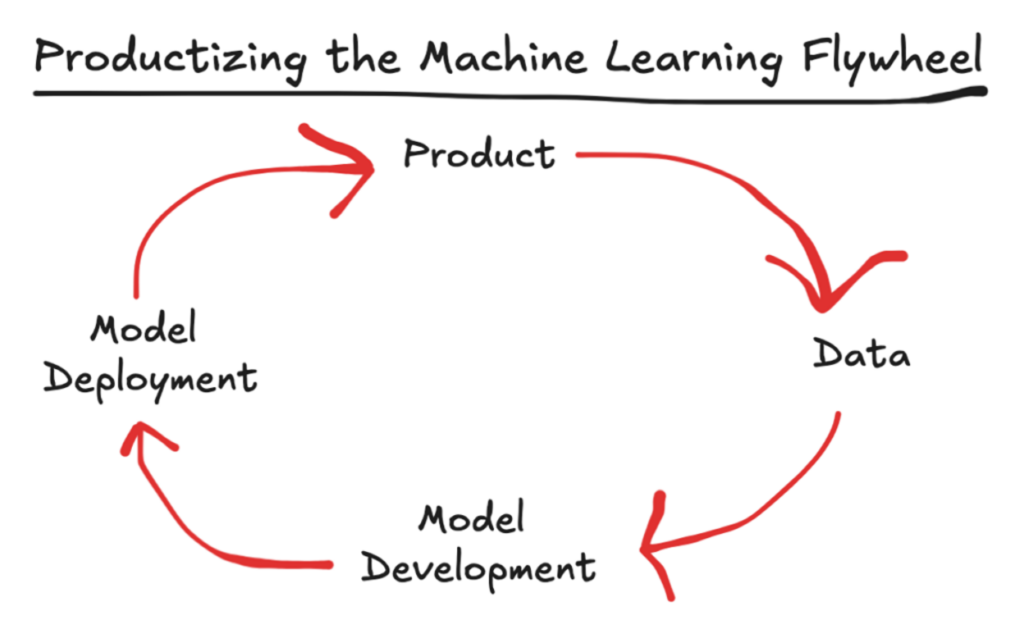

One of the reasons this data is valuable is because it is a core component of the flywheel that digitally-native companies can build around their products. Such flywheels create a compounding analytic advantage because every interaction that a customer has with the product generates data, which can then be fed back in to improve the model, which can then be deployed to generate better, more personalized product experiences for the customer.

Another reason this data is valuable is that, in a post-ATT world, large first-party consumer data sets are incredibly valuable to advertisers.

This is why Amazon’s advertising business, which is built on its treasure trove of first-party data, is one of the fastest-growing and most profitable divisions of the company.

It’s also why we see large B2C companies across financial services, from JPMorgan Chase to Klarna, invest in building out advertising businesses to complement their traditional product offerings.

Bottom line — first-party data has never been more valuable, and the companies that have it aren’t interested in giving it away for free.

B2B2C Service Providers

Over the last couple of decades, legislators, regulators, and consumer advocacy groups around the world have coalesced around a simple but enormously powerful idea — financial data generated by consumers belongs to consumers, and they should be allowed to share it with any company that they want in pursuit of better financial products, experiences, and outcomes.

This idea is commonly referred to as open banking, and it has been operationalized in a variety of different forms and through a variety of different regulatory frameworks in countries around the world, including the U.K., Australia, the U.S., Canada, Mexico, India, Brazil, and Singapore.

Most commonly, open banking leverages the digital technology that consumers use to manage their financial accounts to permission third parties to access specific data from those accounts in order to enable a specific activity or access a specific product or service. On the backend, the financial services providers facilitate the transfer of that data to the third parties, either via an API (the preferred method) or via a technique known as screen scraping (in which an automated service accesses a consumer’s data using their digital banking credentials as if they were the consumer).

This permissioning and data access process is often managed by specialized third parties like MX that sit between data providers, data recipients, and consumers. These companies are commonly referred to as data aggregators.

In the context of the financial data economy, the difference between data aggregators and data brokers is that data aggregators’ businesses are built, 100%, around consumer permission. Hence our usage of the term ‘B2B2C Service Providers’.

As Scott Farrell outlines in his excellent book — Banking on Data — there are three primary functions performed by open banking:

- Granting customers autonomy to require their financial services providers to share their data with recipients of their choosing.

- Enabling the portability of that data so that it can be safely shared by those financial services providers with those recipients.

- Ensuring the accountability of those recipients to the customers for the custody and use of their shared data.

In the U.S., open banking has, to date, been market-driven (via screen scraping and individual agreements between banks and data aggregators) rather than regulatory-driven, but that will change thanks to the CFPB’s soon-to-be-finalized Personal Financial Data Rights Rule.

I’ve written a lot about the specifics of this rule over the last year (read this, then this, then this, if you want to dive deeper), but the basic idea of the proposed rule is to require financial services providers that offer products covered by the rule (deposit accounts, debit, and credit cards, digital wallets) to share customer data with authorized third parties at the request of their customers. This data sharing will be done via standardized APIs, the specifications of which will be provided and managed by an independent standard-setting organization designated by the CFPB (this will very likely be the Financial Data Exchange or FDX).

The impact of this rule on the financial data economy will be immense.

Much of the data that financial services companies buy from data brokers today will become less valuable when those companies can easily get similar or superior data directly from consumers.

One example of this that I like to use is inquiries.

Inquiries are a record of all the times that a consumer has applied for credit. They are captured in the credit file and are a significant factor in most credit scoring models because they are a lagging indicator of financial distress (if you lose your job, one common cash flow management strategy is to load up on credit before you start missing payments).

By contrast, consumer-permissioned bank account data can give financial services providers a real-time view of a consumer’s cash flow situation, which is a much more useful way of assessing their ability to pay and any emerging signs of financial distress.

The formalization of open banking in the U.S. via the CFPB’s rule will have a catalyzing effect on the ability of companies to leverage consumer-permissioned financial data to develop more innovative products and services and compete more effectively for the most valuable customers.

To understand why this is — why a regulatory framework for open banking will advance the use of consumer-permissioned financial data beyond what we’ve achieved with a market-driven approach — picture the difference between driving on this road:

Versus this road:

Historically, open banking in the U.S. has been fury road. It was chaotic and messy. There were no clear on-ramps, exits, or traffic lanes. There were no rules or traffic signs. It was not always clear to the consumer who had their data, how long they would have it, or precisely what they would do with it. Fuel efficiency (i.e., data minimization) wasn’t a priority. And while anyone was allowed to drive on the road, the biggest cars on the road (i.e., the big banks) were the ones in control.

The intended future of the open banking ecosystem in the U.S. — which we’re already well on our way to, as more than 76 million consumer accounts are now actively utilizing FDX’s API — is more akin to a modern highway. Use of the road is governed by a common set of rules and standards, not market power. There are designated on-ramps (for consumers’ granting permission), exits (for consumers to revoke access), and traffic lanes (for consumers to control which third parties see which data). And safety (via APIs instead of screen scraping) and fuel efficiency (data minimization) are paramount.

As we move closer to that future, the frequency and intensity of the fights between different participants in the financial data economy increases.

Data, Data Everywhere, And Not a Lot of Agreement

Let’s use BNPL as our example.

The big three credit bureaus have been working hard, for years, to get the major BNPL providers in the U.S. to furnish repayment data to them. The bureaus recognize that the growth of BNPL and its lack of representation within the core credit file represents a large and expanding gap in their data coverage (especially regarding consumers’ capacity to handle more debt), and they are determined to close that gap.

The BNPL providers don’t want to furnish their data to the credit bureaus. The reasoning that they give publicly is that they and the credit bureaus aren’t technically and operationally ready (yet) to handle the furnishment of BNPL data. There’s some truth to this, but I think the more important reason is that they simply don’t want to give an asset away for free only to have to buy it back and watch their competitors (banks and other BNPL providers) gain access to it as well.

This reluctance on the part of the BNPL providers to share data extends beyond the credit bureaus and into open banking as well. To my knowledge, none of the big BNPL providers have built data-sharing integrations with the open banking data aggregators because, again, the BNPL providers understand that their first-party data is an asset, and they want to protect it at all costs.

However, this reluctance to embrace open banking may be forced to an end if the final version of the CFPB’s Personal Financial Data Rights Rule ends up covering pay-in-4 BNPL products. This seems likely to me given that the CFPB recently clarified through an interpretive rule that it does consider pay-in-4 BNPL products to be Reg Z accounts (i.e., similar to credit cards) for the purposes of consumer protection.

These fights are happening across every product category and use case in financial services, and some (not all) are slowly being resolved as the CFPB finalizes its rules around open banking, the FCRA, and a myriad of smaller financial data economy issues.

That work will continue, but as it does, I would like to take this opportunity to offer a few suggestions about how the CFPB (and other policymakers) should think about how to shape the future of the financial data economy.

Shaping the Future of the Financial Data Economy

The biggest thing that we need to think about regarding the future of the financial data economy is how to align the interests of consumers, financial services companies, and the industry as a whole.

Companies and the data brokers they work with will often try to frame the ways in which they use their customers’ data as being beneficial to their customers. This framing is usually deeply unconvincing.

Yes, we’re selling your data to a whole bunch of third parties without your explicit and granular permission, but don’t worry! You’re going to get more personalized and highly targeted ads in exchange! This is good for you!

On the other end of the spectrum, I sometimes hear consumer advocacy groups push for restrictions on data sharing that, while well-intentioned, would have some significant negative consequences for the industry if adopted on a broad scale.

We like reporting rental payments to the credit bureaus. Every property management company should be required to do that for free, and they should only report positive data. No negative data should be furnished because it’s bad for consumers.

Neither of these extremes is exactly right.

Just because you say consumers will benefit from your data-sharing practices doesn’t mean they will. This is an especially difficult claim to believe when the company is directly profiting off of the sharing of that data.

And just because the furnishment of negative data can impair the ability of individual consumers to access financial products doesn’t mean that it still isn’t the right thing to do for the ecosystem, especially if the data is being shared for free.

We need to think differently.

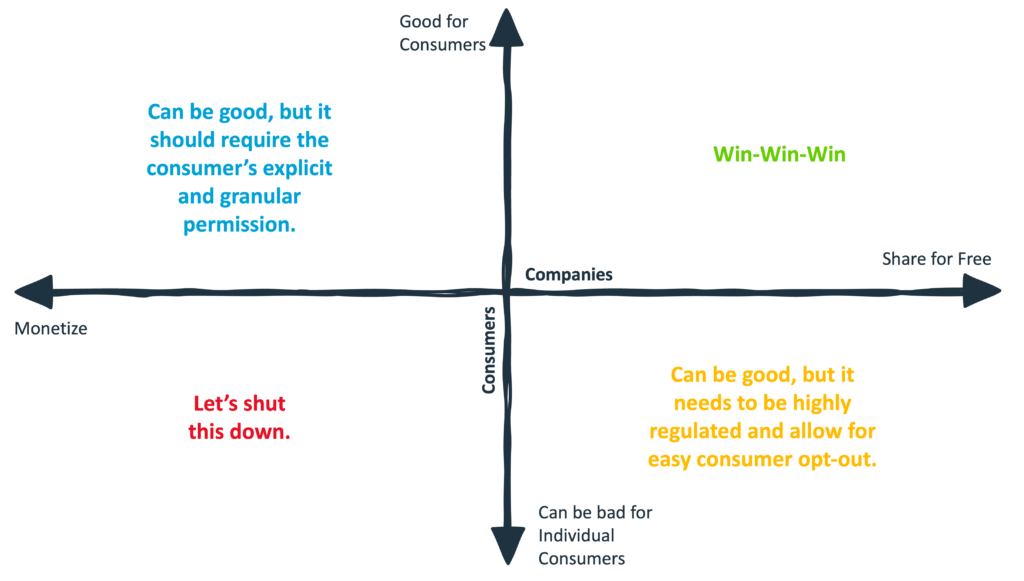

Specifically, I think we should be asking the following two questions:

- Are companies directly monetizing their customers’ data, or are they giving it away for free?

- Will the data being shared be good for all customers, or is there the potential for individual customers to be harmed?

By asking these questions, we can get to a framework for regulating the financial data economy that balances the interests of consumers, companies, and the industry overall.

It looks like this:

Let’s start with the bottom-left quadrant.

Companies should not be allowed to monetize their customers’ data if that data can be used to harm their customers. Period.

A good example of this is the recent plight of a man named Romeo Chicco.

Last year, Mr. Chicco attempted, unsuccessfully, to get auto insurance from seven different providers. When he finally succeeded on the eighth attempt, he ended up paying nearly double the price that he had been paying previously.

The reason for this was a negative report from LexisNexis, the data broker and consumer reporting agency (CRA), which had assembled data on his driving habits. That data was sold by GM, which had sneakily obtained Mr. Chicco’s “consent” to share his driving data with third parties when he checked a box to sign up for GM’s connected car app at the dealership after he purchased a Cadillac.

This is the financial data economy at its worst, and it must be stopped.

But what about cases in which the customer isn’t being harmed? Should companies be allowed to monetize their customers’ data when it’s for the customers’ benefit? WHAT ABOUT THE PERSONALIZED MARKETING OFFERS ALEX?!?

OK, OK, I hear you.

I think it’s fine, but here’s my thing with this quadrant of use cases — prove it.

If you are delivering all of this value to consumers, let’s require that you get explicit and granular permission to share their data.

I’m not talking about checking a box in some privacy policy that no one will read. I’m talking about explaining to consumers exactly what data you will be using, how you will use it, and giving them the visibility and control to easily revoke that permission whenever they want.

One wonders how successful JPMorgan Chase or Klarna would be in monetizing their customers’ data (in the form of advertising) if their customers were given this level of visibility and control over the use of their data. The pressure to earn (and retain) that permission would be a helpful motivator in building the best possible products and services for consumers.

The next question is whether there are use cases for financial data that can lead to adverse outcomes for individual consumers but still be beneficial to the industry overall?

The obvious example is credit reporting.

While I’m sure lenders would love to be paid by the credit bureaus for the data they furnish to them, I personally take a lot of comfort from the fact they are not compensated. If you are sharing consumers’ data without their explicit and granular permission and that data creates adverse outcomes for some consumers, you better be sharing it for a very good reason.

Creating a dataset that can be used to price risk accurately is a very good reason. It’s beneficial for all of us if lenders can safely and efficiently evaluate the credit risk of the U.S. adult population.

That said, this quadrant of the financial data economy should be carefully monitored and closely regulated. Consumers should have the right to see the data that is being shared, correct inaccuracies, and opt out of the system whenever they want (and all of those rights should be operationalized in a far more convenient way than they are today!)

The final quadrant is the easiest to get on board with, though it’s also the hardest to land a use case in.

Here, we’re looking for the elusive win-win-win.

What data will companies be willing to share for free to benefit the whole ecosystem that will also lead to positive outcomes for all consumers?

The best example is fraud prevention. Creating industry data-sharing consortiums to identify and screen out fraudsters (bad guys pretending to be someone else) benefits everyone except the bad guys. It (and other similar use cases) should be encouraged.

A few additional notes on this framework:

- Consumers choosing to share their data should always supersede all other rules that govern the financial data economy. As we’ve discussed, there will be reasons why consumers might not want to share data that companies have a legitimate need for. These cases should be governed by other regulatory frameworks, such as the FCRA. However, if the consumer wants to share their data, they should always be allowed to. It belongs to them!

- Along those lines, the CFPB should broaden its Personal Financial Data Rights Rule to cover as many different types of financial data as possible. They have Reg E (deposits, debit cards, and wallets) and Reg Z (credit cards and likely pay-in-4 BNPL) covered, which is a great start. However, the utility of the rule for consumers could be significantly expanded if the rule also included wealth management/investment products (including retirement and pension accounts, money market accounts, and crypto), installment loans (point of sale, personal, student, auto, mortgage), insurance, taxes, and payroll. I doubt we get this in the final rule, but a man can hope.

- The CFPB’s proposed rule includes a blanket prohibition on third parties processing covered data for secondary purposes — i.e., any collection or use beyond what is “reasonably necessary” to deliver the product or service requested by the consumer. I can appreciate why the CFPB is taking this hardline stance. They are trying to shift the entire financial data economy in a more consumer-friendly direction! However, in this specific case, I think the draft rule goes too far. There are secondary uses that are good for the consumer and good for encouraging competition (which is a core goal of the CFPB for open banking). As long as we are giving consumers an opt-in/opt-out mechanism for these pro-consumer and pro-competition secondary uses, I think they should be allowed.

- The CFPB’s proposed rule even restricts secondary use when the consumer’s data is de-identified. This is, to be frank, ridiculous. You’ll notice that I didn’t include anonymous data in my graphic above. That’s because it wouldn’t make sense! Anonymous data can’t cause harm to individual consumers, but it is enormously valuable to companies for fraud and risk model development and product R&D. If companies de-identify consumer data (and are willing to accept the liability for any cases where that de-identification process isn’t done or is done improperly), they should be permitted to do so.

- One last thought — my framework doesn’t contemplate the idea of consumers being monetarily compensated when their data is used, but perhaps it should? Especially when the companies sharing the data are being directly compensated themselves?!? This idea is currently outside the Overton window in data economy policy discussions in the U.S., but I hope that changes at some point.

I recognize that everything I’m advocating for here isn’t likely to happen (at least not right away). However, I do think that the trends shaping the financial data economy (technology, regulation, consumer and societal norms, etc.) are pushing the market in this general direction.

The ways in which financial services companies collect, analyze, utilize, and monetize consumer data are changing. Rapidly.

Banks, credit unions, and fintech companies need to prepare to compete and win in a very different environment than they are used to.

So, let’s end today’s essay with a few pieces of advice for how financial service providers should prepare for that future.

1.) Prioritize insights.

It’ll take a while after the CFPB’s Personal Financial Data Rights Rule is finalized, but eventually, access to consumer-permissioned financial data will become much easier, less expensive, and more reliable.

Access will become a commodity.

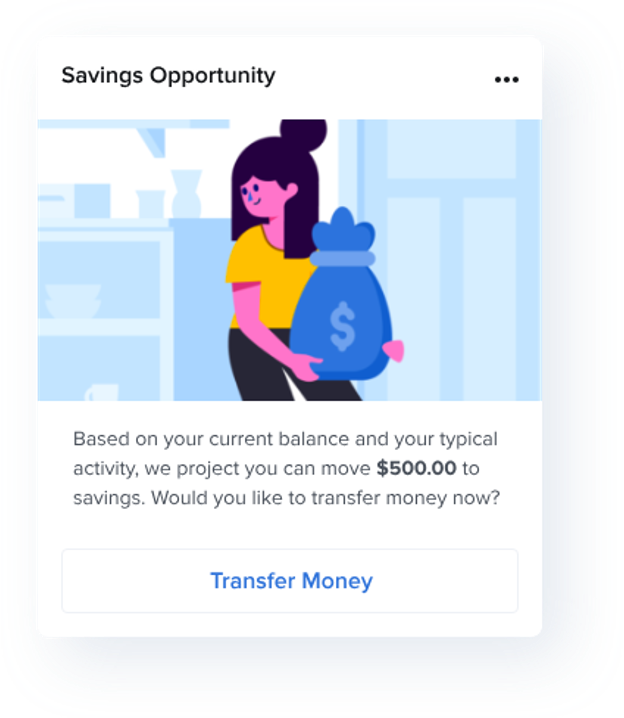

The value will be in transforming that data into actionable insights that are relevant and highly personalized to the financial behaviors and goals of individual consumers.

A simple but extremely powerful example of what this can look like (courtesy of MX) is notifying a consumer that, based on their cash flow, they can afford to move a chunk of money from checking to savings and helping them execute that funds transfer:

This transition from data to insight will be more difficult than many in the financial services ecosystem might assume. We’ve spent decades transforming traditional credit data into useful and predictive attributes and models. When it comes to consumer-permissioned data, we have lots of catching up to do.

My recommendation is to work with service providers that have already gotten a headstart on analyzing this data and generating insights.

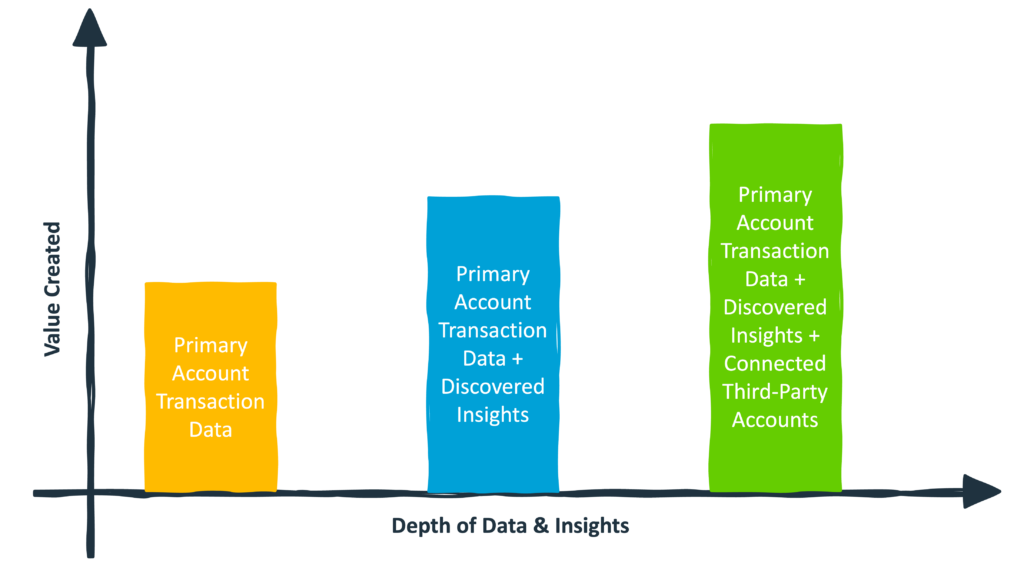

2.) Start with your own data.

Related to the point above, working with new forms of data available through open banking is tricky. A crawl-walk-run approach can be a productive way to get started.

In the context of open banking, this means starting with the account transaction data you already have from your existing customers. Accessing this data is easier (because it doesn’t require customer permission), and it allows you to practice cleaning and transforming the data into a usable format and discovering and extracting new insights that can be inferred from that clean transaction data (i.e., that large monthly payment looks like a mortgage!). After you’ve mastered that, you can work to assemble the full picture of your customers’ financial lives by adding external data aggregation into your user flows and asking your customers to connect their third-party accounts.

3.) Build hooks into your products and experiences.

Once you are ready to start analyzing third-party transaction data permissioned by your customers, you need to figure out how to actually get that permission.

Don’t assume this will be easy.

In the not-too-distant future, every financial services company will be working extremely hard to acquire the permission necessary to see their customers’ full financial lives via open banking.

Indeed, executives at the biggest banks are already talking about this as a competitive necessity. Here’s Bill Demchak, CEO of PNC and noted open banking skeptic:

“We’ll pull share out of smaller banks who won’t have the technology to be able to take advantage of open bank[ing],” Demchak said.

Regulators are “doing this because they think they’re going to lower switching costs,” he said. “All they’re going to do is drain [small] banks of accounts, by big banks who have the technology.”

Here’s the thing, though. It’s not just about technology. It’s about product design and user experience. Are you building compelling reasons for consumers to share their data with you into the context of your products?

Put more simply, what do your customers get out of sharing their data with you?

This will be an enormously important question for product and UX designers in financial services to be able to answer.

(Editor’s Note — Emprise Bank, who is very smart about this stuff, came up with a clever answer to this question, working with MX. Sometimes, simple changes can have a big impact.)

4.) Get ready for generative AI.

And then, of course, there’s generative AI.

If we were to reuse the crawl-walk-run framework from earlier, generative AI would be the equivalent of base jumping.

It’s not something that most banks, credit unions, or even fintech companies should worry about in the short term as a part of their open banking strategies. Focus on the fundamentals first.

However, eventually, it seems inevitable that generative AI will play an important role in all data-driven financial workflows, including those powered by open banking.

Financial services providers will need to prepare for a world in which their autonomous agents are negotiating and transacting directly with their customers’ autonomous agents. They will need to prepare for a world in which profitability will depend on their ability to inspire a little irrationality.

AI will supercharge the next era of the financial data economy. We know this because it supercharged our current era, often with disastrous consequences for consumers, whose data was extracted and monetized with machine learning in ways they never would have agreed to.

It’s incumbent on all of us to move the next era of the financial data economy away from value extraction and toward value creation. And we need to start doing this work now. The future will be here sooner than we think.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by MX.

MX Technologies, Inc., delivers end-to-end solutions that transform data into value for organizations and consumers at every step — from connecting accounts to data enhancement to customer analytics to creating engaging mobile and digital experiences.

MX’s Data Access and Customer Analytics solutions enable financial services providers to seamlessly link and verify financial accounts, as well as unlock actionable insights and analytics from consumer-permissioned data sharing. This creates a comprehensive, clear view of core banking, aggregated, and open banking data for financial providers so that they can better analyze, engage with, and act on data.