The Fintech Takes BNPL Summit happened this week, and it was fantastic.

This didn’t surprise me, given the caliber of speakers, which, when combined with the engaged and highly curious Fintech Takes audience, created some real fintech nerd magic.

We held the event under the Chatham House Rule, so I can’t tell you exactly who said what.

What I can do is share the anonymized version of my notes from the event, which – you’ll be shocked to hear – is organized as a list of nine questions.

1.) What is BNPL?

Buy Now Pay Later.

Next question!

Just kidding.

It’s actually a really good question and one that we spent some time on during the event.

I’m not sure exactly how this happened, but over the last five years or so, BNPL has become one of the best-known and widely-used terms in fintech. My wife’s parents (who subscribe to this newsletter but rarely read this far down, thank goodness) know what BNPL is!

And whenever a term becomes in-laws-level popular, it leads to confusion. This is certainly true with BNPL, which has been used to describe a huge range of different financing arrangements, in both consumer and commercial lending.

This confusion isn’t helped by the fact that the term is also quite a bit older than most folks in fintech realize. Sitting on my bookshelf is a book titled Buy Now Pay Later: A reporter’s examination of the buy-now, go-now, live-it-up-now and pay-later craze in America today – and how it affects you! It was written by a reporter named Hillel Black, and published in 1961.

So, what is a good definition of BNPL, as we understand it in a modern context?

This is what I’ve landed on – BNPL is a form of financing that allows consumers to instantly split their payments for a specific transaction into multiple installments.

The key to this definition is the word “instant”. Modern BNPL is built on top of real-time credit decisioning – the capability for lenders to automatically underwrite consumers for loans for individual, small-dollar transactions. That’s what separates modern BNPL from its point-of-sale installment lending ancestors.

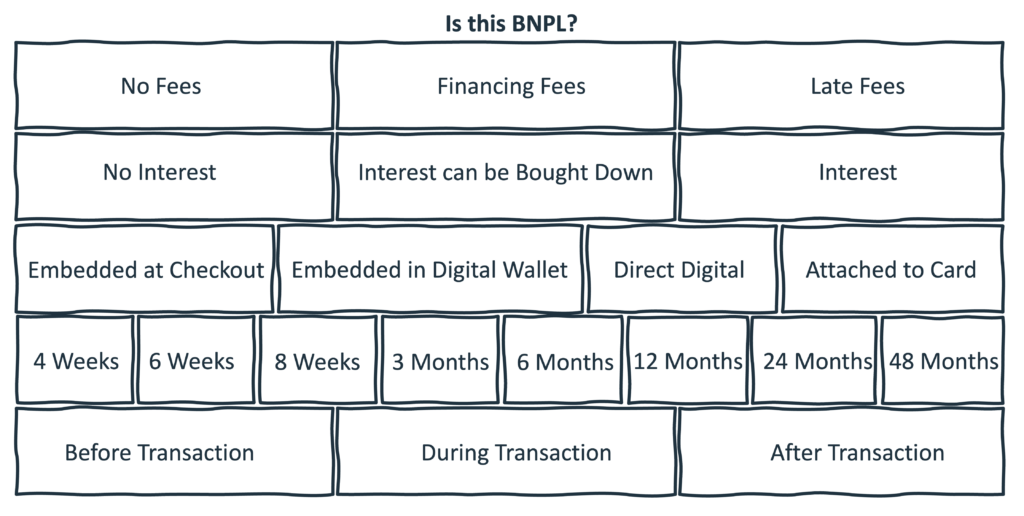

That definition still leaves a lot of room for different product constructs and business models, which is why BNPL is such a fascinating (and occasionally puzzling) space.

Here’s a graphic that shows just some of the different characteristics that modern BNPL products can have:

When you start mapping various BNPL products against these characteristics, you’ll notice just how diverse the ecosystem of products really is.

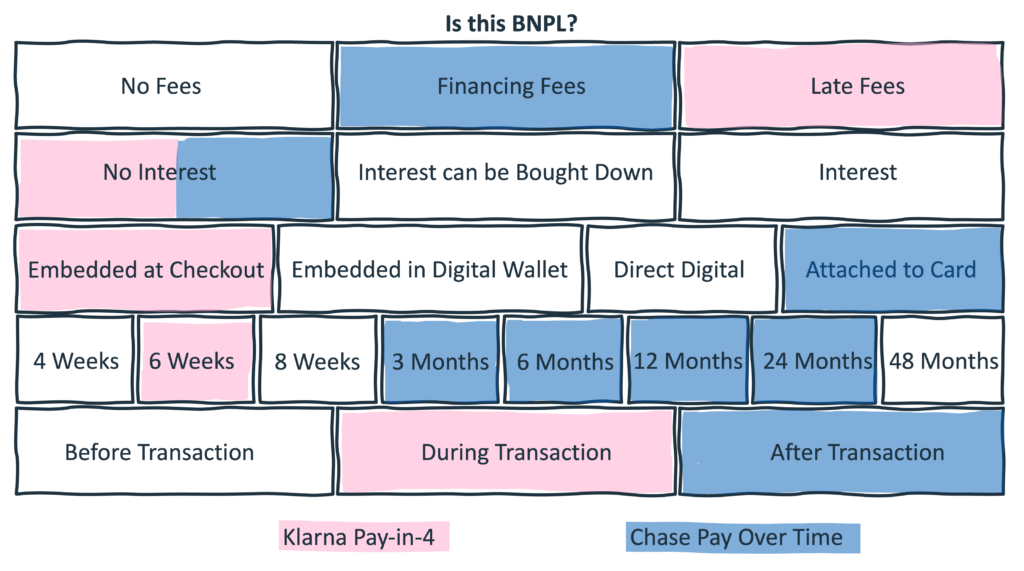

Take, for example, Klarna’s classic pay-in-4 product and Chase’s Pay Over Time product.

Both products are interest-free, but that’s where the similarities end.

The Klarna product has a six-week repayment period. It is presented to the consumer during the checkout process, embedded into the retailer’s website. And, if the consumer misses a payment, they are charged a late fee of up to $7.

The Chase product, by contrast, charges a fixed monthly fee. It is available on most transactions over $100, after the purchase has been made on an eligible Chase credit card. And it has a repayment period of anywhere from 3 to 24 months, depending on the size of the transaction and the creditworthiness of the cardholder.

2.) Who uses BNPL?

This is a tricky question to answer, for a couple of different reasons.

First, whenever you survey consumers, you run the risk of them misunderstanding the question that you are asking them.

One speaker at the BNPL Summit shared an interesting anecdote that touches on this challenge. He was conducting an interview with a consumer. He asked them if they had ever used BNPL before. They said no. He asked them if they had ever used Affirm, Klarna, or Afterpay. They said no. Then he asked them if they had ever used the pink button on the checkout page when they were buying something online. And they said yes.

The second problem is that the term BNPL covers an entire universe of different product structures (as we already discussed), all of which offer slightly different benefits for different customer segments and use cases.

However, if we confine ourselves to just the most popular and fast-growing of those product structures – 0% interest pay-in-4 BNPL – we can narrow it down enough to make two defensible claims:

- In 2023, roughly 20% of U.S. consumers took out a pay-in-4 BNPL loan, which was about double the percentage of consumers who got one in 2021.

- While pay-in-4 BNPL usage is present across all consumer segments, it skews more heavily among women, minorities, young consumers, consumers with subprime or thin/no-file credit histories, low-income households, and financially vulnerable households.

3.) Is BNPL good or bad for consumers?

This is the obvious question. It’s also a bad question. BNPL is too big and too ubiquitous to be able to pin down with a simple good or bad label (though this doesn’t seem to stop many industry commentators and reporters from trying … alas).

Instead, we should interrogate BNPL the same way that we do any other mainstream financial product – by asking how it helps consumers and how it hurts consumers.

And let’s focus, once again, on 0% interest pay-in-4 BNPL, which is what I will be referring to when I say “BNPL” throughout the rest of this essay unless otherwise specified.

4.) How is BNPL helping consumers?

Let’s start on the positive side.

In terms of its structural characteristics, BNPL is the healthiest form of consumer debt that you are likely to find. There is no interest. Users are not able to revolve a balance month over month. The total cost of the loan is transparent and disclosed upfront. And the late fees, when present, are generally reasonable.

Compared to the design, incentives, and business models of almost any other unsecured consumer lending product – credit cards, overdraft protection, payday loans, etc. – BNPL is a healthier option.

Additionally, because BNPL loans are made in small amounts and over short terms, they are generally lower risk for lenders, which means that this product – which plays a critical role in smoothing out cashflow imbalances for many consumers – is typically one of the most broadly accessible consumer lending products out there.

This is a good thing. When consumers are drowning, they will grab onto anything that can help them keep their heads above water. BNPL is a vastly safer liquidity life raft than credit cards, overdraft protection, or payday loans.

(BTW – This is why the handwringing that you see from some consumer advocates about consumers using BNPL to pay for necessities like groceries drives me crazy. What would you prefer they do instead?!?)

5.) How is BNPL hurting consumers?

During one of the sessions at the BNPL Summit, a speaker proposed a very interesting framework for thinking about the relative danger of different forms of credit.

He proposed that credit products sit on a supply-and-demand continuum, and that consumers’ usage of credit products is, to a degree, determined by whether they are more supply-driven or demand-driven.

For example, overdraft protection (despite its many many problems) is demand-driven. The usage of the product requires the consumer’s explicitly opt-in and it is only triggered when the consumer’s demand for more liquidity exceeds what their bank account can supply.

By contrast, the practice of credit card issuers proactively increasing their customers’ credit lines is more of a supply-side tactic. The issuer is adding extra capacity and (in most cases) actively communicating the availability of that extra capacity to the customer in the hope that they will use it. That is supply driving demand.

BNPL offered through merchants at the point of sale is also supply-driven.

Merchants pay BNPL merchant discount rates (MDRs) equal to or greater than credit card interchange fees in order to drive incremental sales. They are paying BNPL providers to get their customers to spend more and more frequently than they otherwise would.

And it extends beyond the checkout page. Many of the major BNPL providers have built incredibly sophisticated advertising businesses, designed to fill merchants’ sales funnels with new (and returning) customers.

Modern BNPL is installment lending attached to an incredibly powerful marketing engine.

That’s not quite as bad as it sounds because, as we’ve already covered, BNPL is generally healthier than other forms of consumer debt. Going on a shopping spree with BNPL, stacking up loans across multiple BNPL providers, is healthier than doing so by maxing out a credit card and revolving the balance over multiple months.

But that’s a bit like saying that eating an entire bag of baked potato chips is healthier than eating an entire bag of fried potato chips. It’s true in a relative sense, but in an absolute sense, you’re still eating a whole lot of chips.

This is where the BNPL companies’ framing of their product’s merits is misleading.

Yes, if you are going to overspend either way and the choice is between revolving a balance on a credit card or using BNPL, BNPL is the better option. But if the choice is between spending more money than you were planning to or diverting that extra money into a savings or investment account, it’s obvious which choice leads to better financial health.

6.) What’s the right balance between credit card usage and BNPL usage?

Let’s set overdraft protection and payday lending – two forms of short-term liquidity that are obviously predatory and are slowly being driven out of the mainstream by regulation and competition – aside.

BNPL’s primary competition is credit cards.

And the question is, what is the right balance of consumer usage, between credit cards and BNPL?

(Editor’s Note – I’d like to include debit cards as a viable third choice here, but American consumers and the American economy run on debt, so it’s unlikely that debit cards will ever meaningfully eat into credit cards’ market share as a spending mechanism. BNPL is a much more promising contender.)

First, we need to establish a baseline for this discussion. How much do U.S. consumers use credit cards? And how much do they use BNPL?

In 2022, the total purchase volume enabled by BNPL in the U.S. was roughly $36 billion. Based on the numbers I’ve seen from Q1 of this year, I would guess that the total for 2024 will be more than double that.

That’s a high rate of growth, obviously. However, it’s important to remember that the total purchase volume enabled by BNPL is still dwarfed by credit card spend, which was approximately $3.2 trillion in 2022.

How much of that $3.2 trillion can be disrupted by BNPL?

A lot, I think!

In addition to BNPL displacing credit card spend, I also think that it can reshape the way that consumers use credit cards.

It’s better if consumers can use credit cards in a more rational way, which means we want to create more transactors (users who pay off their credit card balances in full every month) and fewer revolvers (users who carry a balance month-to-month and rack up interest).

BNPL can help us move in this direction.

In fact, it already is.

According to the CFPB’s most recent biennial analysis of the consumer credit card market, the percentage of credit card customers who are fully paying off their monthly balances has been increasing steadily, up from 36% in 2015 to 44% in 2022. Conversely, the percentage of cardholders who are paying off less than 10% of their balances fell during that time, from 41% in 2015 to 33% in 2022.

One reason consumers have been able to do this is that they are taking advantage of the installment lending features that issuers have been building into cards, such as the Chase Pay Over Time feature that I mentioned earlier.

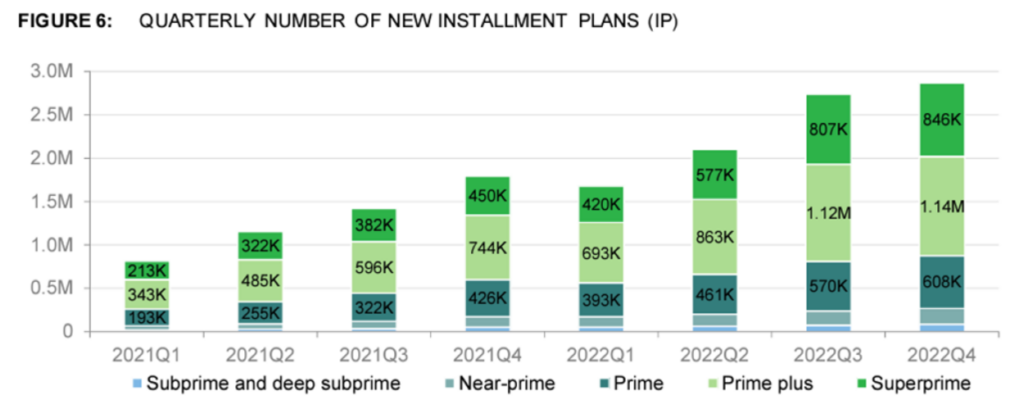

According to the CFPB, the dollar amount covered by these installment plans more than doubled from 2021 to 2022, reaching $9 billion.

This is cool as hell, and it’s evidence that BNPL, as a competitive force in financial services, can drive financially healthier behavior.

Of course, there will be a natural limit to how much spending volume issuers want to enable their customers to move from credit cards to installment plans. Issuers make a lot of money from revolvers (Capital One, especially, which explains its antipathy towards BNPL), and that money helps to fund their credit card rewards programs, which are very popular with customers and serve as a competitive moat against other payments providers.

Still, it’s clear to me that BNPL will continue to eat into credit cards’ market share, especially as providers like Affirm solve for some of the functional gaps between credit cards and merchant-led BNPL with products like the Affirm Card.

7.) Why are lenders worried about the growth of BNPL?

Bloomberg published an article a while back that got everyone in BNPL worked up. Here’s the lede:

It’s hard enough for central bankers and Wall Street traders to make sense of the post-pandemic economy with the data available to them. At Wells Fargo & Co., senior economist Tim Quinlan is particularly spooked by the “phantom debt” that he can’t see.

The article argues that BNPL providers have been reluctant to share data on how their customers are using their products, and that is creating a blind spot for economists and risk managers:

Time and again, they’ve resisted calls for greater disclosure, even as the market has grown each year since at least 2020 and is projected to reach almost $700 billion globally by 2028. That’s masking a complete picture of the financial health of American households, which is crucial for everyone from global central banks to US regional lenders and multinational businesses.

For Quinlan, a major concern is that economic experts are being “lulled into complacency about where consumers are.”

“People need to be more awake to the risk of BNPL,” he said in an interview.

But what exactly is the risk of BNPL?

The Bloomberg article suggests that the risk is the same as it is in all other consumer lending product categories – delinquencies and defaults:

First it was Americans falling behind on auto loans. Then credit-card delinquency rates reached the highest since at least 2012, with the share of debts 30, 60 and 90 days late all on the upswing.

There are signs that consumers are struggling to afford their BNPL debt, too. A recent survey conducted for Bloomberg News by Harris Poll found that 43% of those who owe money to BNPL services said they were behind on payments

I can’t stress this point enough – there is simply no way that 43% number is accurate.

Based on all of the data I’ve seen (hard data, not survey data) and all the conversations I’ve had (both at this week’s Summit and outside of it), the real number is orders of magnitude lower (comparable to or slightly lower than what we’re seeing in credit card).

This makes sense if you think about it.

BNPL – and again, I’m referring to 0% interest pay-in-4 BNPL here – is structurally unlike any other consumer lending product. The dollar amounts are lower (around $250 on average), the repayment period is significantly shorter (6 weeks), and the debt is not open-ended.

It’s extremely difficult for consumers to get into a massive amount of debt or a severe state of delinquency within that product structure, in much the same way that it would be difficult for someone to severely injure themselves by driving a golf cart. The constraints just make it really unlikely.

And the BNPL providers have ZERO incentive, based on their business model, to push their customers into delinquency.

So, what is the real risk of BNPL? Why are lenders right to be worried about it?

I think it’s a behavior thing.

BNPL isn’t causing consumers to rack up significant new amounts of debt, but it is changing the way they manage their week-to-week cash flow. The question of cash or credit becomes significantly more complicated when credit is easily available for individual transactions.

Put simply, BNPL enables transactional cash flow management.

Lenders have spent decades refining their credit underwriting models to understand and accurately forecast consumers’ ability and willingness to pay. BNPL is basically a big rock thrown into this otherwise placid pond, and the ripples have begun to impact lenders in various ways.

For example, while I don’t believe the Bloomberg survey’s finding that 43% of BNPL users are behind on their debt, I do think it’s possible a different finding from that same survey – that 28% of BNPL users said they were delinquent on other debts because of their use of BNPL – might be accurate (or at least directionally useful).

The challenge (and this is where the Bloomberg story got it right) is that it’s difficult to quantify exactly what impact BNPL usage is having on the broader lending ecosystem because BNPL providers aren’t sharing their data.

8.) Why aren’t BNPL providers furnishing data to the credit bureaus?

This was a question that we spent quite a bit of time on during the BNPL Summit.

Here’s the quick history:

- Around 2019, the credit bureaus started exploring how they might incorporate pay-in-4 BNPL loans into consumers’ credit files. They quickly realized that adding it as just another installment loan would be a really bad idea because the frequency of BNPL (even casual BNPL users will take out 8-10 BNPL loans a year) would break the attributes and scoring models that consumer credit files feed into (all of which view frequency as a sign of increased risk).

- Instead of trying to jam BNPL loans into an existing product category within the core credit file or sticking them into a separate file (the bureaus all maintain separate databases for high-APR loan products like payday loans), they decided to create a new product category specifically for pay-in-4 BNPL within the core credit file.

- In order to ensure that this new loan type doesn’t disrupt lenders’ underwriting processes, these new pay-in-4 BNPL tradelines will be partitioned off from the rest of the tradelines, which means that they won’t feed into any attributes or scoring models. The idea behind this strategy is to allow the bureaus to start collecting the data while giving them and other analytics providers like FICO time to figure out the most fair and predictive way to incorporate the data into their attributes and scoring models.

That work took a few years, but as of 2022, the bureaus have said that they are ready for the BNPL providers to start furnishing data.

That hasn’t happened.

Apart from Affirm furnishing data on its longer-term installment loans to Experian (which it has been doing for a while and doesn’t require any special changes on the bureau side) and Apple briefly agreeing to furnish data to Experian for its pay-in-4 BNPL product before killing that product entirely, no major BNPL providers are furnishing data to the big three U.S. credit bureaus.

Why not?

From what I can tell, it’s a combination of different objections:

- The technical objection. There appears to be some disagreement from the BNPL providers as to the technical readiness of the bureaus to actually take in their data. As David Sykes, Chief Commercial Officer at Klarna, told the New York Times, “It’s just not fit-for-purpose yet. And we haven’t seen anything from the bureaus that suggest it’s about to be.”

- The Operational objection. Even if BNPL providers believe that the bureaus are ready, they themselves might not be ready. Furnishing FCRA data comes with certain obligations, including handling disputes from consumers who have concerns or objections regarding their tradelines.

- The credit performance objection. Because pay-in-4 BNPL is a structurally low-risk lending product, BNPL providers are less interested in one of the traditional benefits of furnishing data to the credit bureaus – using the implied threat of furnishing negative data to encourage the customer to make on-time payments.

- The customer value proposition objection. Related to the point above, one of the value props for consumers with pay-in-4 BNPL is the fact that you don’t need to have a credit score to get access to it and that misuse of the product won’t damage your credit score. The BNPL providers may be a little nervous about undermining this value prop (even if pay-in-4 BNPL has the potential to be a great construct for a credit builder product if the data is furnished).

- The philosophical objection. They would never say this one out loud, but I think part of the objection to furnishing data is that the BNPL providers, having grown up in the age of the internet, understand that their first-party data is a valuable asset and, all things being equal, they aren’t interested in giving it to for-profit companies for free.

I empathize with that last objection, but it’s likely that it won’t hold up in the face of another industry trend, which is about to hit the BNPL space.

9.) Will the CFPB’s rule on open banking apply to BNPL?

As you may know, the CFPB’s proposed rule on open banking covers transactional accounts. The CFPB’s definition of transactional accounts includes Regulation E accounts (deposit accounts), Regulation Z accounts (credit cards), and products or services that facilitate payments from a Regulation E account or a Regulation Z credit card (digital wallets).

Those are the accounts from which banks and other data providers will be required to share data at the request of their customers.

The question is if pay-in-4 BNPL loans fall within that scope.

If you define that product type as an installment loan, you might assume no. The CFPB’s proposed rule explicitly does not include other common installment loan products like auto loans and mortgages.

However, if you define pay-in-4 BNPL as more of a transactional payment product, comparable to credit cards, the answer is likely yes.

In related news, the CFPB recently released an interpretive rule regarding BNPL products and Reg Z:

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) today issued an interpretive rule that confirms that Buy Now, Pay Later lenders are credit card providers. Accordingly, Buy Now, Pay Later lenders must provide consumers some key legal protections and rights that apply to conventional credit cards.

While the rule doesn’t specifically address the question of how the CFPB’s work on Dodd-Frank Section 1033 (i.e. open banking) applies to BNPL, it seems reasonable to expect that the bureau will clarify that pay-in-4 BNPL is indeed covered under its open banking framework when the final rule is released this fall.

BNPL providers will need to be prepared to share.