A general critique that I have of banks is that their competence in risk management and focus on short-term profits often interfere with their ability (and even desire) to solve problems for their customers.

Once you learn to look for it, you see this all over the place in financial services. The tens of millions of credit invisible consumers in the U.S.? Yeah, we don’t know how to sort the bad unknowns from the good unknowns in that segment, and we don’t feel like trying to figure it out. The millions of small businesses that struggle to get expedient access to working capital? Eh, our commercial lending processes are highly manual and tuned to the needs of our bigger clients. Sorry.

Fintech has gotten really good at attacking these weak spots (largely because growth-focused startups don’t have the same incentives to prioritize profit and risk management) and forcing banks to respond.

However, there’s one weak spot that banks and, unfortunately, many fintech companies continue to ignore – scams.

The way that most financial services providers think about and deal with scams is infuriating.

Here’s why …

The Difference Between Fraud and Scams

What is the difference between fraud and scams?

A normal person answering this question would likely consider them to be synonymous. If you pushed on them a bit, they might guess that scams are a small sub-type of fraud and fraud is a much bigger and broader category of bad behavior. This is essentially the distinction that English language nerds use:

They are synonyms but have a subtle difference. A scam almost always involves money or transactions that involve monetary loss to the victim. But on the other hand, fraud is a broader term which might involve money or other gains or even bringing disrepute to a person.

Seems reasonable.

But how would a bank or fintech company answer this question?

If you’re hoping that they would have a broadly similar view to the average person, you are going to be disappointed! Their definition is jarringly precise.

Here’s HSBC:

Fraud is suspicious activity on your account that you didn’t know about and didn’t authorise.

A scam involves you making or authorising the payment yourself. You’re persuaded to buy a fake item, hand over your security code or transfer a sum of money, not realising you’re being conned by a criminal.

And here is Chime (which, hilariously, cites the above HSBC article in its own article on the subject):

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Fraud refers to any suspicious activity to your bank accounts that you did not authorize. This might include someone using your debit or credit card number to make unauthorized purchases, logging into your account and locking you out, or full-on identity theft.

So what’s the meaning of “scam”? The key difference is that, in instances of scams, scammers convince you to authorize a transaction or willingly hand over personal information. While scams were around before mobile banking and the internet, the digital era has given rise to new forms of scams.

Well, we certainly can’t fault them for being unclear!

But I wonder … why are they so clear about this, to the point of copying each other’s talking points?

It’s because of Reg E.

Reg E is the implementing regulation (originally crafted by the Federal Reserve) for the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA), a law passed by Congress in 1978 and signed by Jimmy Carter, to establish the rights and liabilities of consumers as well as the responsibilities of all participants in electronic funds transfer (EFT) activities. Among other things, Reg E makes financial institutions (rather than consumers) liable for unauthorized electronic funds transfers as long as they are reported within a specified window of time. Here is how Reg E defines “unauthorized”:

An unauthorized EFT is an EFT from a consumer’s account initiated by a person other than the consumer without actual authority to initiate the transfer and from which the consumer receives no benefit.

Now, remember, the EFTA became law in 1978. At that time, the idea of computers moving money between different bank accounts without human intervention was still quite novel. ATMs had only been in the U.S. for about a decade. The idea of P2P payments or mobile wallets would have sounded like science fiction to even the most open-minded bank executives at the time.

It seems clear (to me, at least) that Congress’s intent in passing the EFTA was to promote confidence in the use of these new electronic financial services capabilities by assuring consumers that they wouldn’t be left holding the bag if a criminal used these capabilities to steal their money.

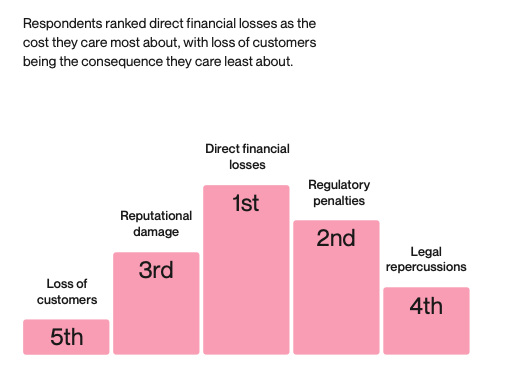

However, when it comes to the EFTA, banks and fintech companies have generally preferred to hide behind the letter of the law – ducking liability for fraud losses whenever they possibly can – rather than live up to its spirit. Not terribly surprising when you consider that the executives responsible for preventing fraud at these institutions tend to see their primary job responsibility as “save the company money”, not “help the customer”. Alloy’s State of Fraud Benchmark Report illustrates this point:

P2P payments is the current epicenter of this cowardly behavior:

About a quarter of bank customers in an October survey by J.D. Power said they or a close relative had experienced fraud via a peer-to-peer service. And according to Consumer Reports, 12 percent of frequent payment app users reported sending money to the wrong person.

In an analysis published this week, [Consumer Reports] determined that none of the four popular payment apps — Apple Cash, Cash App, Venmo and Zelle — reimburse users when a payment is mistakenly sent to the wrong person, because such transactions are considered “authorized.”

The report said the apps also wouldn’t compensate clients if a criminal tricked them into sending money — perhaps by impersonating someone the users know or pretending to represent their bank — because the users, in a sense, had approved the transaction.

This, understandably, befuddles and enrages the users of these apps:

Justin Faunce lost $500 to a scammer impersonating a Wells Fargo official in January and hoped that the bank would reimburse him. Mr. Faunce was a longtime Wells Fargo customer and had immediately reported the scam — involving Zelle, the popular money transfer app.

But Wells Fargo said the transaction wasn’t fraudulent because Mr. Faunce had authorized it — even though he had been tricked into transferring the money.

Mr. Faunce was shocked. “It was clearly fraud,” he said. “This wasn’t my fault, so why isn’t the bank doing the right thing here?”

OK, so you won’t get any help if you are tricked into authorizing a transaction. What about if someone steals your phone when you aren’t looking?

In late 2020, [Bruce] Barth was hospitalized with Covid-19 and his phone disappeared from his hospital room. A thief got access to his digital wallet and ran up charges on his credit card, took out cash at an A.T.M. and used Zelle to make three transfers totaling $2,500.

All three accounts were at Bank of America, where Mr. Barth has been a customer for more than 30 years. When he filed fraud reports, the bank quickly refunded his cash and credit card losses. But it denied his claims for the Zelle thefts, saying the transactions were validated by authentication codes sent to a phone that had been previously used for that account. Bank of America was essentially saying that the Zelle transactions were authorized — even if his phone was stolen.

What if you are mugged?

The trouble started on a hot and humid Saturday night last August when [Colin] Johnson said after a night out with friends, he decided to call it early and head home, walking down Belmont Avenue.

Before he could process what was going on, Johnson said two men approached him out of nowhere, demanding everything he had.

“Obviously, I just handed over my phone and wallet,” Johnson recalled, “And they took off. It’s all kind of a blur.”

“They were able to get into all of my apps right away,” he said. “They were able to change all of my passwords. That’s where the real damage started.”

That’s when the withdrawals started: Hundreds of dollars withdrawn from ATM’s across the North Side, as well as a debit transaction at a Walmart in Skokie.

In addition to the physical withdrawals, another $10,000 was transferred electronically over Zelle, doled out from Johnson’s checking account.

Johnson assumed his federally-insured bank, Citibank, would reimburse the lost funds and have his back.

Instead, quite the opposite happened: In the months that followed the robbery, Citibank declined Johnson’s multiple requests for refunds, as well as his appeals, arguing that Johnson had authorized the money transfers.

This, despite Johnson sharing with Citibank’s fraud department the police report documenting the crime that occurred.

After initially refunding the money robbed from Johnson’s savings, Citibank clawed back those funds, over drafting his checking accounts.

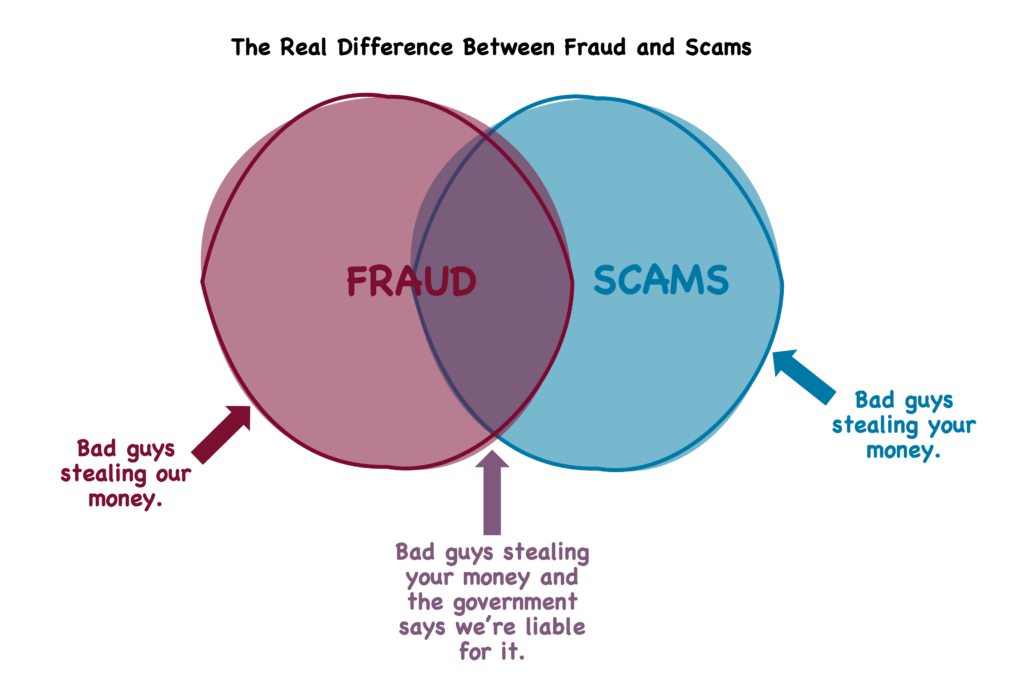

So, again, what is the difference between fraud and scams?

The sanitized, PR-friendly answer that banks and fintech companies give to consumers revolves around the word “unauthorized”. It can be summarized as something like this:

Fraud is suspicious activity that is unauthorized, while scams are mistaken transactions that you authorized, so be careful when making payments and make sure not to misplace your phone, you silly goose!

If banks and fintech companies were honest, here is how they would answer the question:

Fraud is when bad guys try to steal money directly from us or from you in a situation in which we’re legally liable for your losses. It hurts our bottom line, so we take it extremely seriously and invest millions of dollars a year to prevent it from happening. Scams are when bad guys try to steal money from you in situations where we can avoid liability. They don’t touch our bottom line (even though they can ruin your life), so we don’t care!

This is unacceptable for our industry. Consumers use the tools we give them to manage their money and keep it safe. When criminals exploit those tools to steal our customers’ money, that is our problem, regardless of where the liability sits. Banks and fintech companies shouldn’t need to be shamed by bad PR to do the right thing (BofA made Bruce Barth whole after the New York Times called them), nor should they need to be pressured by regulators to do the right thing (Zelle is considering a policy change relating to liability for scams in response to pressure from the CFPB).

Banks and fintech companies should do the right thing for their customers because, long term, doing the right thing for customers is the best way to create value and generate sustainable profits.

So let’s imagine what that might look like. What would it look like if a bank or fintech company decided that scams were their problem and set about really solving for them?

Since Valentine’s Day is next week, let’s use romance scams as our example.

Bad Romance

A romance scam is a type of fraud in which a criminal feigns romantic intentions towards a victim, gaining the victim’s affection and then using the resulting goodwill to get the victim to send money to the scammer under false pretenses.

The scam requires patience and a deft touch (you’re trying to get someone you’ve never met or seen to fall in love with you), but it can be extremely lucrative. According to the FBI, Americans lost more than $1 billion to romance scams in 2021, up from $362 million in 2018.

Romance scams are, by all accounts, one of the fastest-growing types of fraud, and the reason for that is heartbreaking – people are lonely. The rapid growth of romance scams in the last couple of years underscores this point. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people were isolated from friends and family. Their only outlet for socializing was the internet, which has, unfortunately, become an ideal hunting ground for romance scammers. Elderly consumers are especially vulnerable and are a more appealing target for criminals because they have more money:

The median loss from a romance scam for people 70 and older in 2021 was $9,000, according to the F.T.C., compared with $2,400 across all age groups.

“I’ve seen elders mortgage their houses, borrow large sums of money from their neighbors, empty out their retirement accounts,” said Michael Delaney, a Chicago-based lawyer who specializes in elder law.

Here are the basics of how a romance scam works:

- The scammer reaches out to the victim through a dating app, social media site, or another digital platform. They use a fake identity and profile picture and often claim to work in a profession that could plausibly have them working abroad with limited access to the internet (claiming to be enlisted in the armed forces is a popular lie, for example).

- The scammer exploits the victim’s loneliness and desire for connection to quickly establish a bond with them. They paint an appealing picture of a life that the two of them could have together in the future. They will usually try to convince the victim to move their communication off of the dating app or social media site to a more private communication channel, like email or text.

- The scammer constructs a plausible and emotionally compelling reason for why they suddenly need money – paying for a plane ticket so they can finally meet the victim in person is a very common one. They provide specific instructions to the victim on how to provide them with this money, which can even include taking control of their computer through a remote desktop tool like TeamViewer in order to assist them (this is especially common with elderly victims who may be less tech-savvy). The actual methods of payment vary, from ACH and wires to gift cards and crypto.

- The scammer attempts to keep the scam going for as long as possible, never meeting with the victim in person but providing plausible reasons for canceling or delaying. This goes on until the victim catches on or they run out of money.

Romance scams are a blight on our society, and while no amount of outside help or intervention can completely stop them (or any scam), it would be nice if banks and fintech companies collectively decided that enough was enough and fully dedicated themselves to addressing it. If they did, here are five things they might consider doing.

#1: A new focus for transaction monitoring. The transaction monitoring that banks and fintech companies do today is optimized to detect two things: 1.) behavior that is indicative of fraud that the company is liable for and 2.) behavior that is indicative of money laundering, which all financial services providers are obligated to identify and report. A lot of brain power has been spent building machine learning algorithms and investigative tools to efficiently detect these two things. However, hardly a spare thought has been spent on designing transaction monitoring to detect authorized-but-suspicious customer behavior that might be indicative of a scam. Imagine if we started paying more attention to this. I’m not an expert in machine learning, but it’s not hard to see the outlines of an effective algorithm for detecting romance scams targeting elderly consumers by combining data elements like “customer age” and “historical transaction volume and velocity”. And if you can detect a scam in real-time, you can take steps to introduce additional friction into the customer’s experience (“are you sure you want to send this?” “can we tell you more about the warning signs for romance scams?”) to slow them down and encourage them to think carefully.

#2: Better identification of coerced and coached behavior. Related to the point above, it would go a long way to detecting romance scams if banks and fintech companies had more sophisticated and precise tools for measuring “in session” behavior. How is the customer interacting with the online banking portal or mobile banking app? Does the way that they are moving through the screens suggest that someone is coercing or coaching them through the process? Are they using a remote desktop tool like TeamViewer? Are they taking screenshots of the portal/app? These things can be known if you have the right technology in place and you understand what types of signals to look for.

#3: A consortium for everyone. Another thing that would help in stopping these scams is the ability to know, in real-time, if the account that a customer is trying to send money to has ever been associated with fraud in the past. This is an easy problem to solve. Indeed, banks solved it a while ago through the creation of fraud data consortiums like the one that Early Warning Services (EWS) built in the 1990s to allow banks to share data with each other on known fraudulent deposit accounts. The trouble with bank-led consortiums like EWS is that they are closed to non-bank competitors, like money transmitters, neobanks, and crypto exchanges. This is counterproductive. In financial services, fraud is everyone’s problem. And sharing data about fraudsters is a responsibility that should blanket the industry as broadly as possible.

#4: Solve for money-adjacent relationship problems. A while back, I wrote:

Money plays a foundationally important role in many different types of relationships. It causes couples to fight. It stresses out parents who don’t feel that they’re adequately preparing their children to go out into the world. And it creates a lot of awkward silences between adults and their elderly parents.

What’s weird is that there aren’t any traditional bank products specifically designed to solve these money-adjacent relationship challenges.

In that essay, I argued that the next grand challenge for banks and fintech companies is to build software products to help people and companies solve the money-adjacent problems that traditional bank products ignore (or even exacerbate).

Romance scams targeting elderly consumers are a good example of where this type of relationship-focused software could add value. These scams are often stopped by the children of the victims, who learn (sometimes months or years into the scam) about their parents’ new “romantic relationships”. There has to be a better way to prevent this problem and, more broadly, to make the experience of children helping their aging parents manage their finances easier, more intelligent, and more empathetic. Why isn’t there a Ramp-like expense management software product designed to do exactly this?

#5: Find a balance between self-service and relationship banking. Somewhere over the last 30-40 years, banking changed, and major life milestones went from being a thing you chatted about with the teller at your local bank while depositing a check (We’re moving in together!) to a thing that automatically triggered the most soulless and cringe-worthy cross-sell offers imaginable (Buying your first home? Get a mortgage with us!).

My response to the CFPB’s recent longing for the days of relationship banking was largely critical, but I do think the bureau has a point – the digitization of banking has left very little room to be human. This isn’t a problem for most of us most of the time. We just want to use self-service tools to deposit that check or pay someone back for lunch and then get on with our lives. But there are a few key moments, like in the immediate aftermath of a divorce or the death of a spouse, when our lives become briefly unrecognizable to us, and the Capraesque qualities of relationship banking become essential.

One thing that all scams have in common is that they exploit the vulnerabilities that we all share as humans. Finding ways to insert humans back into digital experiences will be essential to helping consumers stay safe from scams.