I like stablecoins.

As someone who has a pathological hatred of financial speculation, especially when it is packaged as a product feature, stablecoins — a type of cryptocurrency that is designed to maintain a fixed value over time — have always been one of my favorite product categories within crypto.

As I have written previously, stablecoins are crypto stripped of speculation.

Perhaps because of this, stablecoins have also been one of the most durable product categories within crypto. Regardless of bitcoin’s price, stablecoins have just chugged along over the last decade, drawing steady interest and investment from incumbents like Visa and (more recently) Stripe.

However, as enthusiasm for crypto surges in the wake of President-elect Trump’s victory (and the appointments of pro-crypto folks like David Sacks and Paul Atkins), I’m starting to see some signs that the stablecoin “brand” (stable, responsible, low-risk) is being used, in a hand-waving kind of way, to make strange and risky crypto ideas appear safer and more mainstream than they actually are.

It’s kinda like your teenage daughter dating a boy who wears a blazer every time he comes over to your house to pick her up. Yes, it’s superficially comforting, but it’s important to remember that just because he’s wearing a blazer doesn’t mean you shouldn’t worry about him.

Let’s take a look at a couple of examples that have recently come onto my radar.

Stablecoins Will Replace Credit Cards?

While stablecoins are often presented as a solution for modernizing cross-border payments (Matt Brown at Matrix has a good write-up on cross-border payments if you are curious to learn more), I’ve not seen them pitched as a replacement for traditional rails for domestic payments use cases.

Until now. Here’s Sam Broner, partner at a16z:

Stablecoins found product-market fit in the past year — not surprising since they are the cheapest way to send a dollar, enabling fast global payments. Stablecoins also provide more accessible platforms for entrepreneurs building new payments products: no gatekeepers, minimum balances, or proprietary SDKs. But large enterprises have not yet woken up to the substantial cost savings — and new margins — available to them by switching to these payment rails.

While we’re seeing some enterprise interest in stablecoins (and early adoption in peer-to-peer payments), I expect to see a bigger experimentation wave in 2025. Small-/medium-sized businesses with strong brands, captive audiences, and painful payment costs — like restaurants, coffee shops, corner stores — will be the first to switch from credit cards. They don’t benefit from credit card fraud protection (given in-person transactions), and are also the most hurt by transaction fees (30 cents per coffee is a lot of lost margin!).

We should also expect larger enterprises to adopt stablecoins as well. If stablecoins indeed speedrun banking history, then enterprises will attempt to disintermediate payment providers — adding 2% directly to their bottom line. Enterprises will also start seeking new solutions to problems credit card companies currently solve, like fraud protection and identity.

There are numerous problems with this analysis.

The biggest one, which Jareau Wade pointed out on Twitter last month, is that most of the costs for electronic payment networks have nothing to do with the actual money movement. That part is just changing numbers in databases, which we already know how to do very cheaply. Instead, the costs result from other very important jobs-to-be-done within the payments value chain, including coordination, security, regulatory compliance, and fraud management.

Stablecoins, by themselves, don’t solve for any of those jobs-to-be-done, except, perhaps, security, which makes the cost comparison between them and credit cards irrelevant.

Additionally, this analysis ignores the fact that credit cards aren’t merely a payment method for consumers. They are also a source of liquidity (supplied by the revolving credit line) and rewards (funded, partially, by merchant interchange fees). It’s unclear to me how stablecoins will compete with credit cards in those areas.

People have been predicting for years that crypto would replace credit cards. Merely swapping in the term “stablecoins” for crypto in that prediction doesn’t magically make it make more sense.

Unless the restaurants, coffee shops, and corner stores Sam references are located in a country with an unstable local currency, I don’t see how this prediction is any more likely to come true.

(Editor’s Note — for a much more thoughtful take on what would be required to replace the card networks with a system built on DeFi rails, check out this thread from Frank Rotman.)

Stablecoins-as-a-Service > Banking-as-a-Service?

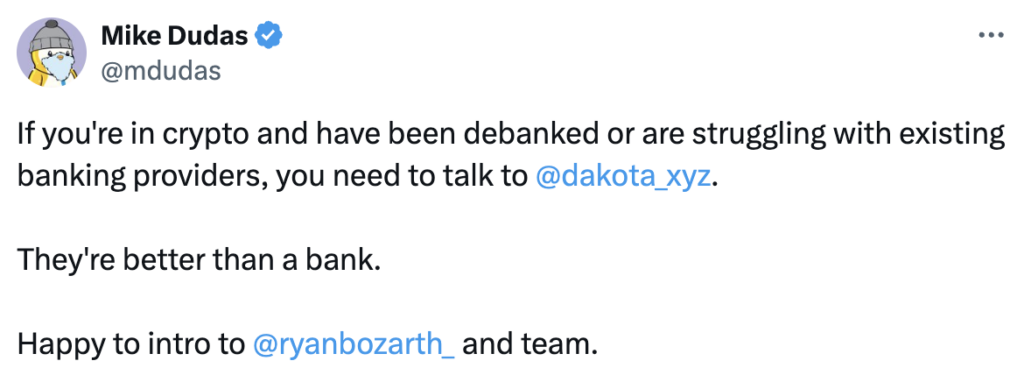

In the wake of the recent furor over debanking, Mike Dudas (Managing Partner at 6MV, a crypto-focused VC firm) suggested that crypto companies worried about debanking work with one of his portfolio companies, a crypto-native business neobank called Dakota:

Dakota describes itself as a “modern banking platform, powered by stablecoins and backed by U.S. Treasuries”:

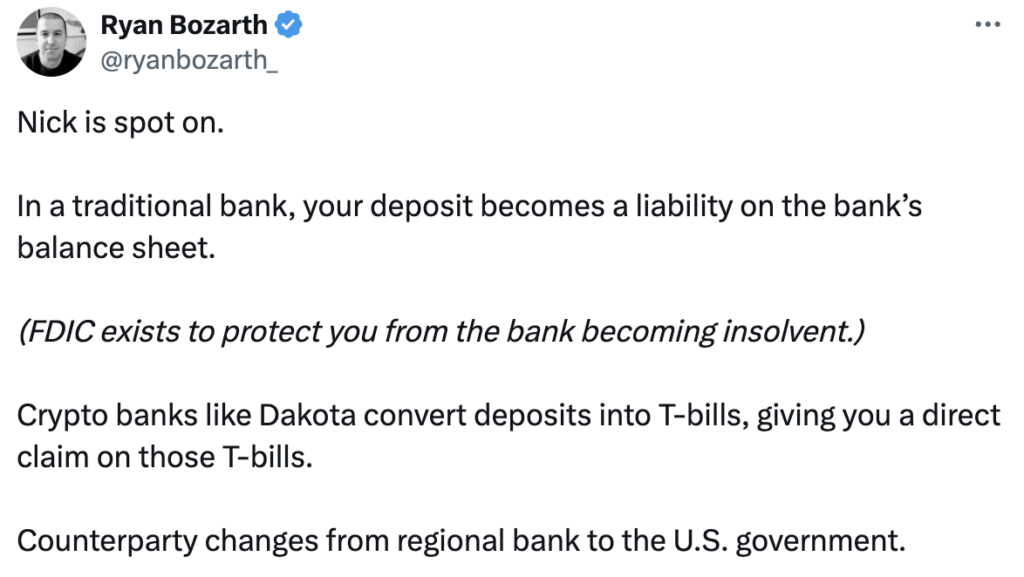

The CEO of Dakota explained on Twitter that the benefit of this approach — using stablecoins instead of regulated banks to store customers’ deposits — is safer because rather than lending your money to a bank (which might lose the money by making bad loans), crypto banks like Dakota convert customer deposits into T-Bills, giving customers “a direct claim on those T-Bills”:

That sounds great, but it leaves me with a lot of questions.

How does Dakota buying T-Bills with my deposits give me a direct claim on those T-Bills? If Dakota fails, what’s the process for me to submit a claim to the U.S. government to get my money back? How does Dakota ensure that customer assets don’t get co-mingled or end up getting trapped in bankruptcy proceedings, as happened with Voyager and now Synapse? What regulator is overseeing Dakota and ensuring that they have good answers to these questions?

(Editor’s Note — I asked Ryan some of these questions on Twitter but did not receive answers by the time this essay was published.)

These are the exact problems that the FDIC, with its expertise in resolving failed banks, specializes in solving.

In its FAQ section, Dakota says that it does not offer FDIC insurance. This is an important clarification, as Dakota also says in the disclosure at the top of its homepage that its U.S. banking partners “are FDIC members,” as well as mentioning further down on the homepage that “Deposits and balances are protected by top insurance plans.” (this is apparently in reference to cyber, crime, and E&O insurance that Dakota has as a company … not deposit insurance for customers).

Confusing!

And what about the risk that the stablecoins backing these deposits aren’t actually as stable as Dakota claims?

Don’t worry! According to Dakota’s FAQs:

Since deposits are held as stablecoins like USDC and backed by U.S. Treasuries, the need for traditional FDIC insurance is mitigated. Stablecoins provide a safer, more transparent option, as they are issued by regulated entities that regularly demonstrate proof of reserves.

OK, so USDC. That sounds good. Circle (the issuer of USDC) is known to be a reputable company that takes trust and transparency seriously.

Am I correct in assuming that all Dakota deposits are automatically converted into and held in USDC?

Nope!

From Dakota’s terms of service:

By default, fiat currencies sent into the Dakota Platform are automatically issued and converted into Dakota’s proprietary stablecoin DKUSD (“DKUSD”).

OK. Is there any information on Dakota’s website about DKUSD? Perhaps an attestation from a reputable accounting firm about what mix of assets DKUSD is backed by?

Nope!

There is a way to make this model work, as Austin Campbell helpfully outlined on Twitter, but it’s very complex and requires exceptional execution to pull it off. And to be honest, it just doesn’t seem worth it when BaaS, enabled through a direct relationship with an FDIC-insured bank, is sitting right there as a perfectly viable alternative.

I like stablecoins as much as the next guy, but I’m not wild about this sudden impulse to shoehorn them into every banking and payments use case we think of.