I am obsessed with this question.

The reason I am obsessed is because, despite what the proponents and detractors would have you believe, this is not an easy question to answer!

Pay-in-4 BNPL (which is the flavor of BNPL that most folks, including me, focus on) enables consumers to finance small purchases (usually between $100 and $300) at the point of sale (usually online), by paying 25% upfront and the remaining balance in three two-week installments, with 0% interest and (usually) no fees.

The argument made by BNPL proponents is that pay-in-4 BNPL loans are structurally safer and more accessible than credit cards. Because there is no interest and no ability to revolve a balance month-over-month, there is no chance that consumers will end up trapped in debt. And because the loan amount is small and the repayment term is short, the BNPL provider can afford to take on more risk (i.e., if someone doesn’t pay back their $100 loan, the BNPL provider will know within two weeks if there’s a problem they will only lose $75 max), which allows them to extend loans to more consumers (e.g., subprime and credit invisible consumers).

That’s all very fair!

The argument made by credit card proponents is that their product provides far more utility to consumers than BNPL. Credit cards are general-purpose payment and credit instruments, meaning they can be used to pay for or finance anything sold by any merchant that accepts them (which is most merchants). Credit cards also provide usage-based rewards, which are deeply popular with consumers.

That’s also very fair!

And credit card issuers and BNPL providers have taken steps, in recent years, to address some of the comparative weaknesses in their products by taking leafs out of each others’ books.

BNPL providers have launched hybrid pay-in-4/debit card products designed to provide the same ubiquitous and flexible payment and credit capabilities as credit cards without the revolving debt (e.g., the Affirm Card).

Credit card issuers have launched embedded, post-purchase installment lending features, allowing customers to split large purchases (usually over $100) into fixed installments for a fee, providing an alternative to revolving debt for customers that need help stretching their cash flow (e.g., American Express Plan It).

These incremental innovations have proven popular. Affirm reported that it had more than 1.4 million active cardholders at the end of its latest fiscal quarter. And, as I wrote about a year ago, credit card issuers’ embedded installment lending capabilities are being used at rates that have surprised industry observers (including me).

That’s all great, but we’re still no closer to answering our question — which product is better?

Are credit cards with installment lending features (and maybe more of an Apple Card-like UI?) the best solution?

Or is a hybrid BNPL product (perhaps leveraging Visa’s new Flex Credential?) the superior choice?

I NEED AN ANSWER!!!!

Untangling The Messy, Multiparty Value Props of Credit Cards and Pay-in-4 BNPL

OK, let’s apply some first principles thinking here.

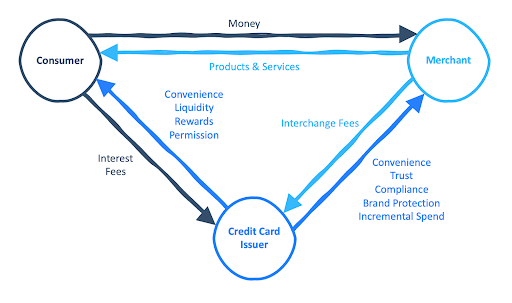

At the simplest level, merchants have products and services, which consumers want, and consumers have money, which merchants want.

Any common medium of exchange (debit cards, cash, gold, stablecoins, etc.) can be used to facilitate this exchange.

Where things get tricky is when you add in credit.

Credit is essential to merchants. It’s difficult to guess how much less they would sell if their customers didn’t have access to credit, but suffice it to say that it would be a massive amount.

Indeed, if you rewind the clock 100+ years in the U.S., merchants were the primary lenders to American consumers, not banks. This makes intuitive sense. Underwriting consumers for credit at the point of sale has, for most of history, been extremely expensive. No one really wanted to do it, but merchants had to do it because it was a critical driver of their growth and profitability.

But it wasn’t fun. Lending isn’t fun. It’s risky. It’s expensive. It’s fraught with legal and reputation landmines. And when it comes to collecting on delinquent debts, it’s downright unpleasant.

Big merchants (think Sears) didn’t mind because they had the scale to do it well. But everyone else loathed it.

So, when the general-purpose credit card launched in Fresno, California in 1958, it was quite a hit with small merchants. Banks solved the “underwriting individual purchases at the point of sale is impractically expensive” problem by underwriting the consumer, giving them an open credit line that they could use across multiple merchants.

The result, for merchants, was a convenient, trusted, and compliant payment and credit option that protected their brand (we’re not the ones hassling you about overdue bills, Bank of America is) and drove incremental sales.

For consumers, the benefits were access to a more convenient and flexible form of liquidity, rewards (which took some time to develop into what they are today), and “permission” to overspend.

(Editor’s Note — on that last point about permission, I think it’s inarguable that the credit card has played a key role in the growth of the post-WWII credit culture in the U.S. For evidence of just how much things have changed in this regard, check out this news report from 1993 about credit cards being introduced Burger King.)

For the banks, credit cards became a uniquely profitable and resilient growth driver, allowing them to balance revenue generated through merchants (via interchange fees) and through their customers (via interest on revolving balances and fees).

And everyone lived happily ever after!

Just kidding.

In the last 60 years, the credit card industry has attracted significant criticism, some of it fair and some of it unfair.

Let’s start with the fair criticisms.

Credit cards are an extremely expensive form of unsecured credit. Interest rates are high and unpredictable. Fees can be excessive. Revolving debt compounds. And, worst of all, much of the $645 billion in revolving credit card debt carried by U.S. consumers (as of Q3 2024) is the result of impulse rather than strategy.

Rewards, which consumers are extremely fond of, are funded (in part) by the interest paid by consumers that revolve a credit card balance. This strikes some as unfair, essentially a tax paid by those who aren’t savvy or disciplined enough to use credit cards as transactors.

The unfair criticisms fall more on the merchant side of the equation.

You may have heard that merchants aren’t fond of paying interchange fees. This has been the subject of quite a few lawsuits over the years, as well as intense lobbying and public relations campaigns designed to convince policymakers and the general public that interchange fees are a tax on small businesses and a significant contributor to the high costs that consumers pay at checkout.

This argument is mostly bullshit.

I absolutely believe that Visa and Mastercard engage in anti-competitive behavior (which should be carefully policed), but the theory that high interchange rates are what stand between consumers and lower prices has been conclusively refuted (it turns out that when you lower fees for merchants, most just pocket the difference … imagine that!)

Most merchant discontent on interchange fees comes from a small number of large merchants (Walmart, Amazon, Target, etc.) who (like Sears before them) have reached the scale to cost-effectively facilitate commerce via in-house payment and lending solutions. To the extent that smaller businesses complain about credit card fees, my theory is that these merchants have internalized all the benefits of credit cards while fixating solely on the cost.

Put differently, if credit cards disappeared tomorrow, most merchants would be very sad.

Or maybe not!

Because now we have pay-in-4 BNPL!

Whereas credit cards solved the “underwriting individual purchases at the point of sale is impractically expensive” problem by underwriting the consumer for a multi-purpose credit line, BNPL solved the problem using technology. By integrating directly with merchants and leveraging automated credit decisioning, BNPL companies made it feasible to underwrite consumers’ individual purchases in real time.

(Editor’s Note — Today, consumers will use BNPL to finance purchases as small as a hamburger at a fast food restaurant. Imagine how people in 1993 would have reacted to that!)

The result is, in many ways, a much simpler product than credit cards.

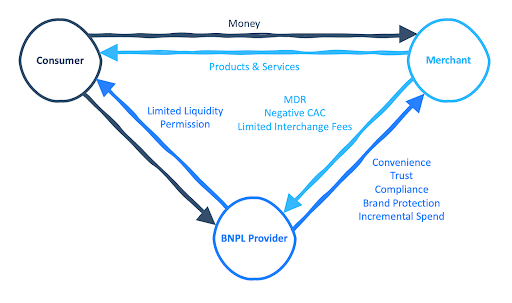

Merchants get the same convenient, trusted, and compliant payment and credit option that protects their brand (we’re not the ones hassling you about overdue bills, Affirm is). And they get, arguably, even greater levels of incremental spend because the financing option can be presented to the consumer programmatically in the exact places in the commerce journey where it will make the biggest difference.

BNPL providers benefit from this arrangement even more than credit card issuers do. There are two reasons for this.

First, by driving an even greater level of incremental sales revenue for merchants, BNPL providers can charge a higher percentage (referred to as the merchant discount rate or MDR) than credit card issuers charge (anywhere from 1.5 to 3 times as much).

(Editor’s Note — BNPL providers also commonly make money from merchants via interchange when they offer a payment card like the Affirm Card and through first-party advertising that drives the consumer back to the merchants.)

Second, unlike credit card issuers, which have to spend money to acquire new customers, BNPL providers actually get paid to acquire customers, as the majority of their new users come through their integrated merchant partners, which have no interest in the unpleasant aspects of lending such as collections. This “negative CAC” advantage for BNPL providers is a significant edge.

On the consumer side of the equation, the value exchange is a bit light.

Assuming the BNPL provider isn’t charging any fees to the consumer (which is true in most cases), there’s really no hard cost for them. However, there’s also not much in the way of direct value for consumers. BNPL provides a similar shop-till-you-drop permission structure to what credit cards provide. BNPL provides some liquidity (the Affirm Card’s pre and post-purchase financing capabilities are a good example), but it’s far less and less flexible and convenient than what credit cards provide. And while some BNPL providers like Klarna have tried to create credit card-like rewards programs, they haven’t (yet) cracked the code (and I’m skeptical that they can, given the unit economics).

The result is a rather unbalanced triangle.

But is this unbalanced triangle good or bad?

Unhelpfully, I think it’s both!

Let’s start with the good.

BNPL is basically free money for consumers. Unlike credit cards, there are no fees or interest, and BNPL providers don’t have an incentive to encourage consumers to take out debt they can’t afford to pay back.

Now, the bad.

As we already covered, pay-in-4 BNPL has limited utility for cash-strapped consumers. You don’t want to take your car into the shop hoping the mechanic accepts Sezzle. The lack of rewards is also a bummer, although you could argue that it’s the price that transactors should pay to protect revolvers from themselves (that sound you hear is Kiah Haslett screaming into the void).

The biggest thing is the permission structure. Because BNPL providers are entirely dependent on merchants for revenue, they are incentivized to go even further than credit card issuers to encourage their customers to shop. This is why the big BNPL providers spend so much time helping their merchants optimize their online checkout pages and why their mobile apps look disturbingly similar to Amazon.com. They’re not trying to drive consumers into debt that they can’t afford to pay back, but they are trying to keep consumers in the maximum amount of debt that they can afford.

How exactly does this commerce incentive in BNPL play out in the real world?

I’m glad you asked!

The CFPB Weighs In

The CFPB recently released a report based on data provided by six major BNPL providers (Affirm, Afterpay, Klarna, PayPal, Sezzle, and Zip). The dataset contains approximately 145 million BNPL applications from 2017 through 2022 and it has been matched against those borrowers’ corresponding de-identified credit records.

The report is worth reading in its entirety, but here are a few of the most interesting and (for our purposes) relevant findings:

- BNPL is big, but it has lots of room to grow. In 2022, the CFPB estimates that the six covered BNPL providers originated approximately 277 million BNPL loans with a gross merchandise value of roughly $34 billion. To place this number in context, it represents approximately 1% of total spending on credit cards in the same year.

- BNPL is heavily focused on subprime borrowers. From 2021 to 2022, the CFPB estimates that consumers with deep subprime and subprime FICO scores accounted for over 60% of all originated BNPL loans. Borrowers without a FICO score (i.e., credit invisible consumers) accounted for approximately 4% and borrowers with near-prime, prime, and super-prime FICO scores accounted for the remaining 35%.

- BNPL borrowers stack loans, but rarely default. Of the 21% of consumers using BNPL loans in 2022, over 62% were currently using multiple loans, with 32% using simultaneous loans from different providers, in a practice known as loan “stacking.” It’s unclear from the data how much of this behavior is strategic (i.e., trying to maximize available credit by going to multiple lenders) vs. circumstantial (i.e., different merchants offer different BNPL options). However, the good news for BNPL providers (and not a surprise to me) is that default rates for BNPL were significantly lower than they were for credit cards. From 2019 to 2022, average BNPL default rates (defined as the percentage of originated loans that were 120+ days past due) were consistently below 3%.

- Most BNPL users also use credit cards. According to the CFPB, over 80% of BNPL users in 2022 had active credit card accounts. And those credit card accounts continued to get used. The CFPB found that the average credit card utilization rate for BNPL users was between 60% and 66% and, alarmingly, tends to increase after the date of first BNPL use. And while BNPL default rates are low, the default rates for BNPL users’ credit card accounts are much higher, averaging 10% between 2019 and 2022.

I’ll Take “Unanswerable Questions” For $2,000, Alex

So, what’s the answer?

Is BNPL better for consumers than credit cards?

I don’t know. The CFPB doesn’t know. Know one knows. It’s too early to say.

My hunch, at this moment, is that the following three statements are true:

- Use of pay-in-4 BNPL and use of credit cards are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are increasingly linked together (and BNPL providers should furnish data to the credit bureaus!)

- A credit card is a better product if it is used in a healthy and responsible way.

- A pay-in-4 BNPL loan is a better product if it is used in an unhealthy and irresponsible way.

But I could be completely wrong!